So this Sunday on Game of Thrones, Ramsay Bolton and Jon Snow will (finally, Christ, that took forever) face off in the so-called Battle of the Bastards, pitting a ragtag gang of outcast scamps led by a pouty, pure-hero type against a heavily fortified (and favored) death army led by a prancing sadist chump. You can be assured of the following:

- For, like, the 8 billionth time, Ramsay will do something heartless and ultraviolent to remind the audience that he is a bad person.

- There will be long swaths of prebattle silence with the two sides just staring each other down from a considerable distance, soundtracked only by flapping flags and cawing crows and cool ambient shit like that.

- The scamps will be losing badly until — doo doo-doo doo! — a triumphant horn or rumbling pack of horses or whatever announces the arrival of surprise reinforcements from Littlefinger or the Tullys or some obscure character who only appeared for 10 seconds in Season 2.

- A beloved character or two will die, and the prancing sadist chump will either not die or die in an unsatisfying way, probably offscreen, as see last episode’s breathtaking triple-anticlimax.

- It will still be pretty awesome.

We better pregame. You know what all this reminds me of?

Fuck it, we’re watching Braveheart.

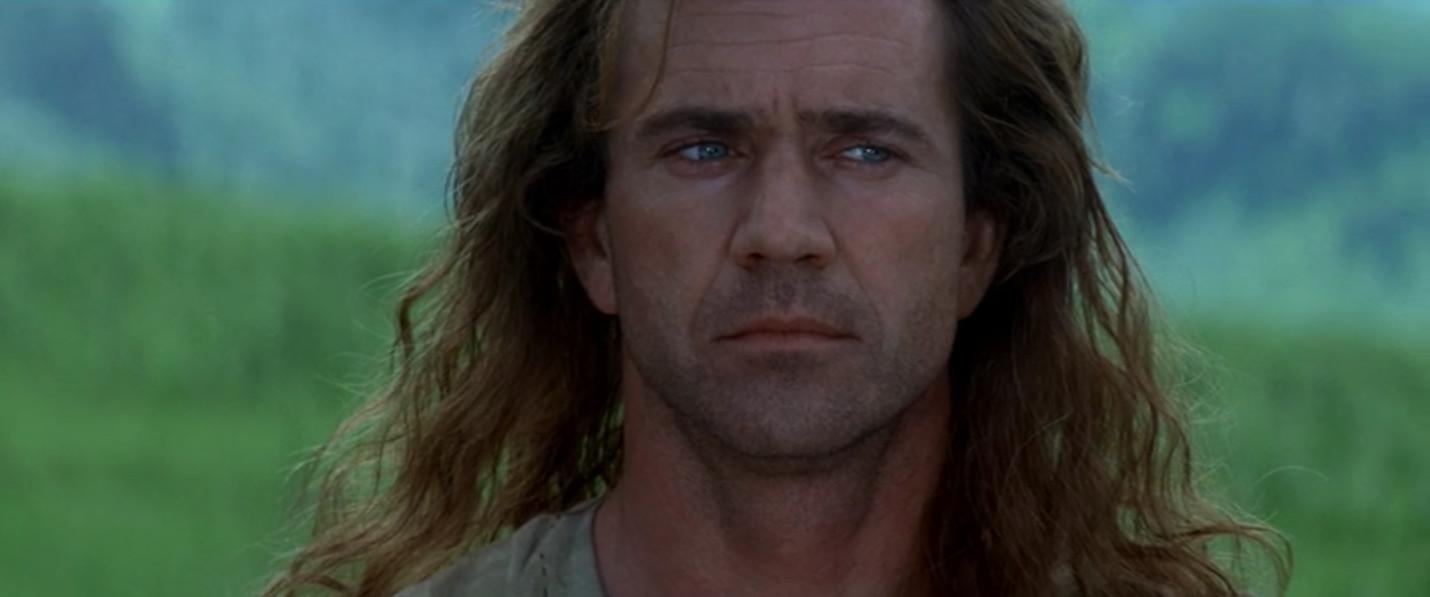

What Mel Gibson is smelling there are The Winds of Arbitrary Critical Reassessment. Braveheart (1995), which he directs and stars in as 13th-century Scottish folk hero William Wallace, was both (arguably) his cultural apex and (inarguably) Scotland’s. The bounty: five Oscars, including Best Picture and Best Director, albeit in a down year, beating out such wan competition as Babe (George Miller tho!), Dead Man Walking, and Apollo 13. (Also Martin Scorsese’s Casino, which only got one major nomination, for Sharon Stone, hmm, hmmmmmm.) Within Mel’s personal narrative, at this point he had three Lethal Weapon installments down and one to go, with Maverick the year before and Ransom the year after; he didn’t direct again for nearly a decade. (The Passion of the Christ, eesh.)

No, for Mel, this was pretty much as good as it gets. (He wasn’t in that.) Braveheart is streaming on Netflix, FYI; also FYI, it’s fuckin’ long. Just a few winding, wistful uilleann pipe melodies short of three full hours. Your star attraction doesn’t show up for 20 minutes, though this kid is a decent child-actor approximation, or at least they got the eyes right.

All right, so let’s break this down as best we can. Is this movie legit, or was it just good enough for the mid-’90s?

Your Star Attraction

Mel Gibson is great in this! He’s lovely. He’s certainly more charismatic and less whiny than, say, Jon Snow or Robb Stark or whomever, though of course that ain’t saying much. He bounds into view and immediately starts throwing rocks at his friends’ heads, adorably; for the brief interval when he’s a simple, peace-loving man, there is a distinct rom-com goofiness to his manner, with a dazzling, palpable charm down to his very teeth.

Whereupon his one true love dies and he immediately starts beating ass.

This, too, though, he does with unlikely charm and relative grace, save for a confusing late sequence when he turns into a morally ambiguous ninja assassin of random traitors, roasting up dudes and drowning his own horse and so forth. (That flying horse looks fake as hell — this beloved horse-action scene is more believable — but consider the alternatives.)

The gig naturally requires him to make several rousing dentist’s-office-motivational-slogan-type speeches about FREEDOM, with the London Orchestra churning along in maximum-uplift mode behind him. And though these orations are not the pinnacle of the form — I myself prefer Bruce Campbell in Army of Darkness, in this or any other respect — he pulls us through it. It’s absurd on its face to describe a three-hour sweeping war epic with 50 extra-cramming battle scenes as “understated,” but, as a whole, both Mel the Actor and Mel the Director manage to not totally exhaust you. Whether 20 years of subsequent cinematic carnage have just desensitized us to the excess here is a valid question, and will be coming up a lot.

The Romance

Again, this part doesn’t last very long, but as the humble and plainspoken Murron MacClannough, Catherine McCormack is perhaps better off confined mostly to dream-sequence cameos, given the script. Her precious few clandestine dates with William are awkward affairs — he brags about speaking French, she mentions that she doesn’t know how to read, that sort of thing — that mostly involve stuff like this:

WILLIAM: ’Course running a farm’s a lot of work, but that will all change when my sons arrive.

MURRON: So you’ve got children.

WILLIAM: Well, not yet, but I was hoping you could help me with that.

There is a second love interest, eventually, in the person of Isabella of France, who is thirsty indeed for William’s heroism, or at least for his heterosexuality (more on this in a sec); that those two eventually hit the sack is one of this film’s many delightful historical inaccuracies, which also include the kilts, the blue face paint, most of the characters’ motivations and actions, and the fact that they somehow forgot to put a bridge in the Battle of Stirling Bridge. Just roll with it, man.

The Other Actors

They’re fine. Accent quality is generally high, as compared with Game of Thrones and its ilk, though many combatants are clearly engaged in an unofficial R-rolling contest. Look out, though, for this guy …

… as putative Scottish king Robert the Bruce, who looks like an uncredited Eagles rhythm guitarist and has particularly scrambled motivations and a copy of the script that was mistakenly printed in all caps. “I DON’T WANT TO LOSE HEART,” Robert the Bruce yells, and he certainly doesn’t. Thankfully, he is confined largely to (usually) quiet scenes opposite his father, Scottish Emperor Palpatine, who is a bad guy, sorta.

The Villain

But your actual bad guy is Patrick McGoohan as King Edward I, a.k.a. King Longshanks, who demolishes all comers in the the r-rolling contest (“Scottish rebels have rrrrrrrrrrrrrouted one of my garrisons”) and talks like Donald Sutherland on helium (“The trouble with Scotland is that it’s full of Scots”). He could probably be digitally inserted in Robin Hood: Men in Tights without anyone noticing, but he somehow spins ridiculousness into villainous gravitas anyway. (CONFESSION: When I first watched this movie in high school, my buddies and I would giggle like idiots whenever anyone onscreen said “Longshanks” both long and loud enough that it drowned out a lot of dialogue and made it difficult to follow the plot.) Alas, his most memorable scene has aged, ah, poorly, and was a huge bummer to begin with.

The Problem

So Longshanks’ son, Prince Edward, as played by Peter Hanly, is established as gay sometime between five and 20 seconds after his first appearance onscreen, during his marriage to Isabella of France, which he mostly spends looking back at his trusted confidant, English Jim Morrison.

This is the most likely point when Mel Gibson’s actual sordid personal history will intrude on your enjoyment of this film, which does indeed feature a scene when Longshanks tosses English Jim Morrison out a window. Whether Gibson plays this event for laughs is debatable, but at least in some theaters, laughs are what it got, to very understandable dismay. What I can tell you is that as poorly as Braveheart handles this, Game of Thrones does not depict, say, Loras Tyrell’s homosexuality with much more delicacy — just more nudity. Things in this realm may have not gotten worse, but nor have they gotten much better. These days it’s mostly children being pushed out of windows. Which brings us to …

The Violence

Braveheart is, on the one hand, obviously insanely bloody, with all variety of head-smashing and -stabbing and -singeing, and it may be the apex of the “two giant armies run full-bore at each other” battlefield epic. (Thousands of extras were most definitely grievously harmed in the making of this film, along with several hundred horses.) But it doles out its gratuitousness with just a click more restraint than you’ll probably expect here in 2016, which is less an indictment of you than of 2016, obviously. Your mother will not like these parts, but they won’t make her leave the room, either. There’s a lot of that thing where an oblivious total rando is standing perfectly still in the midst of a wild, chaotic brawl, only to suddenly get mega-owned by an axe or a spear or whatever, and it’s hard not find this a little amusing no matter how gnarly it gets.

But yeah, eventually Wallace starts slaughtering dudes pretty much at random, when the internal treachery and backstabbing and super-wussy talk of “compromise” begins (there is no dirtier word in Scotland, evidently). You’ll likely forget who any of his victims are, exactly, in a very GOT-esque sort of way, and by now we’re way past the two-hour mark, so if you’re familiar with this jam at all, you’re also bracing yourself for …

The Last 20 Minutes

Yeah, this is just Mel Gibson being tortured. It’s not as gnarly as I remember, which sounds horrible to say and is horrible to say, and that’s definitely 20 subsequent years of cultural desensitization talking. Feel free to fast-forward or bail out entirely at any time. Unfortunately, Gibson and GOT and Hollywood as a whole went on to conduct themselves as though the last 20 minutes of this movie is the most important and crowd-pleasing part, and the hell with it.

Conclusion

“Feel free to fast-forward or bail out entirely at any time,” applies to this movie as a whole, really — it’s silly and soapy and overwrought on principle (they really ought to have cooled it with those uilleann pipes) and profoundly unpleasant when it wants to be, which it does, often. But if you regard Game of Thrones as a gritty reboot, it’s fascinating to view this through that prism, as a somehow kinder, tamer, sillier, more restrained piece of source material. It’s probably not as great as you thought it was in 1995, and nowhere near as terrible as you fear it’ll be now. Braveheart is not bad. You may, however, find yourself wishing it were harder to watch.

HBO is an initial investor in The Ringer.