Donald Trump, ‘Bloom County’ Slumlord

A close reading of Berkeley Breathed’s run-in with the Donald

By Raymond Cummings

In the late 1980s, cartoonist Berkeley Breathed was bored — and for Bloom County readers, his lack of inspiration was palpable. The comic strip that had spent the Reagan ’80s lampooning so many aspects of period culture astutely and mercilessly — race relations, presidential politics, runaway conservatism, feminism, MTV’s rise, the Cold War, scientific progress, tabloid absurdity, general corporate fecklessness — was running on fumes in the Bush I era. Mirroring the destiny of Peanuts’ Snoopy, Opus the Penguin had risen in status from diminutive, monosyllabic pet to overcommercialized avatar. The title story from 1989’s The Night of the Mary Kay Commandos, in which Opus left in search of his long-lost mother and stumbled into an animal-cruelty nightmare, was Bloom County’s final premillennium peak. For any longtime fan, the final collection Happy Trails! (1990) made for an excruciating read. The most frightening horror lurking in Breathed’s Anxiety Closet was another eight years of daily setups and punch lines.

Enter Donald Trump. Then in his early 40s, the New York real estate mogul had been cast by the national media as a living, breathing personification of soulless opulence: forcibly evicting tenants to accelerate a demolition; megalomaniacal, piling up failed business ventures (Trump Airlines, the New Jersey Generals, Tour de Trump); showcasing the sneering, world-baiting hauteur of a wrestling heel, a role he would later actually play. This is the man who admitted, in his 1987 book The Art of the Deal, that he’d “do nearly anything within legal bounds to win.” The man who, in 1989, asked a Time magazine reporter, “I mean, really, who knows how much the Japs will pay for Manhattan property these days?” The man who said in a 1990 Vanity Fair profile that he’d “never buy [his first wife] Ivana any decent jewels or pictures. Why give her negotiable assets?” One was hard-pressed, at that moment in time, to find a more powerful, loathsome figure in American life — or a more deserving icon for Breathed to roundly whack-a-mole as the strip marched to its end. Bloom County presented America with a fun-house mirror version of itself and wrung extra weirdness from already-weird public figures: among many others, Michael Jackson, Madonna, Gary Coleman, Sean Penn, Dan Rather, and Gregory Peck. But the 1980s were ending, their moments had passed, and — this is crucial — most of Breathed’s rogues were talents who in some way enhanced public life. The strip thrived on the era’s neon-splashed shallowness, which felt informed by a certain well-meaning earnestness. Trump’s every action and utterance embraced reckless shallowness with such vengeance that he almost had to surface in Bloom County; his presence in this strip, in retrospect, feels almost inevitable.

Doonesbury creator Garry Trudeau, a Breathed nemesis, first made Trump a target in 1987, a contemporary pop monster for Duke to serve. Trudeau’s antipathy for the Donald was plain to see, and while Doonesbury’s variegated needling was a mixture of disgust and prescription, he unwittingly helped burnish Trump’s legend.

Breathed had other ideas.

This is purely theoretical, but humor me here: I often wonder if Trump was incorporated into Bloom County, not to make the strip funnier, but as a gesture of self-sabotage — to somehow make Bloom County even less funny than it already was. Read enough Bloom County and the self-loathing becomes instinctive; it seems possible to me that Breathed included Trump as a sort of comic slumlord, to hasten and legitimize Bloom County’s impending demise.

In any case, that’s what happened. There was minimal setup. When a falling anchor gravely injures Trump, Bill the Cat is kidnapped, and Trump’s brain is transplanted into Bill’s body. Ironically, Bill the Cat — a gross Garfield parody whose state of being generally vacillated between comatose, inebriated, and deceased — would be, at this point in the series, at his most voluble. Bill’s default mode up to that point was a dazed, vegetative silence; repurposed as Trump’s mouthpiece, he emerged as a relative blabbermouth.

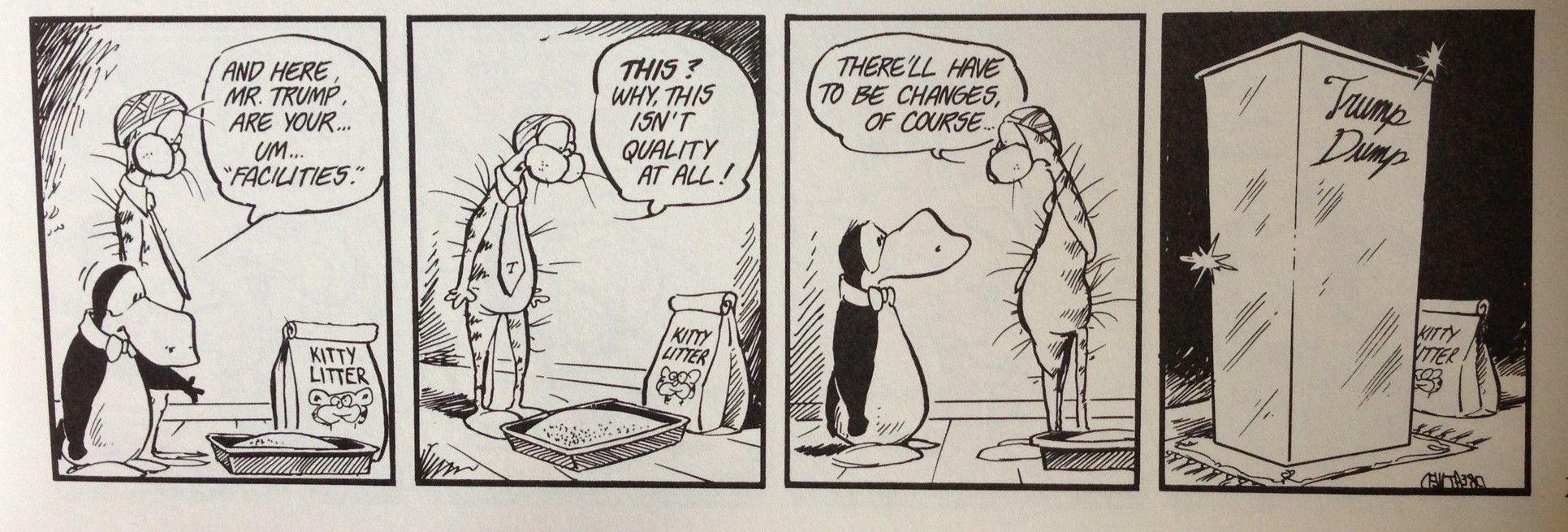

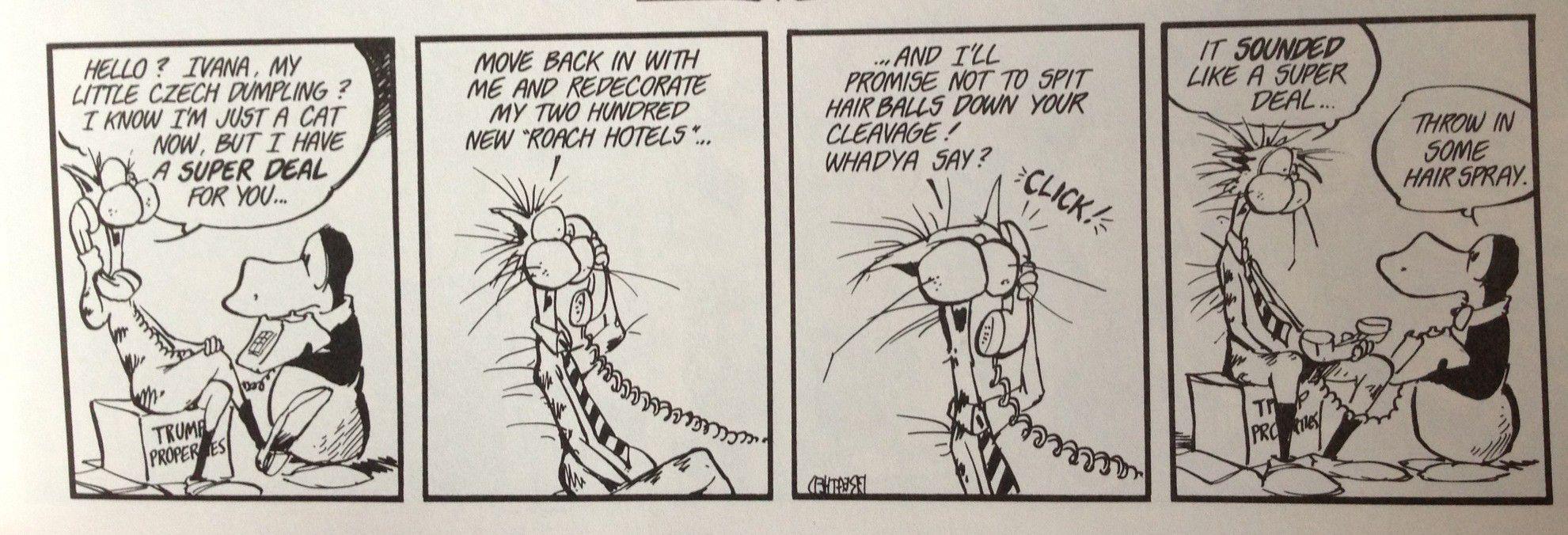

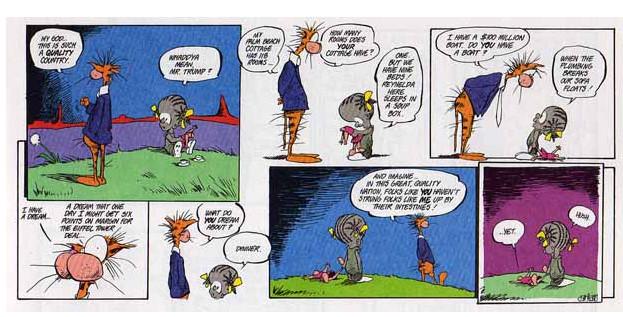

Breathed milked Bill-as-Trump for a month solid. As in real life, Bloom County Trump is an arrogant, greedy ass. Again and again, Breathed riffs repeatedly on the idea that Ivana could sell “an earring to feed Africa for a year,” as though Breathed were determined to avoid any degree of backhanded valorization. Trump, lounging in an inner tube christened the “Trump Princess II,” demands a gold-plated litterbox. Upon arriving at the boardinghouse — where he’d later purchase all the roach hotels — Trump declares, “Ya know, this place could be real quality if it had 300 more floors to it.” Trump sees his name in the stars. Trump calls Ivana, seeking reassurance that he’s still worth a fortune or begging her to let him come home.

Through Opus, Breathed offers his Trump multiple opportunities to display some shred of humanity; they’re all rebuffed. Most of the cast seems indifferent to his presence. These are predictable, unhumorous strips, as though by denying Trump the ability to amuse or provoke, Breathed was illustrating how boorish and empty the Donald was. It’d be easy to believe this if not for one very notable exception.

This strip above is among the earliest appearances of Ronald-Ann, a little girl from Bloom County’s “wrong side of the tracks” who represented part of Breathed’s awkward, late attempts to reckon directly with urban America. Her corner of this universe is a shadowy, malevolent nightmare, a one-dimensional no-man’s land of flying bullets and unfinished background sketches. Breathed tended to use his core characters as his — and the audience’s — avatars in cultural bewilderment. Playing Ronald-Ann’s material poverty against Trump’s material wealth, the cartoonist struck a strong populist note; it’s one of those moments where Bloom County chose poignancy over hilarity. Here he perfectly anticipated our modern class divide, and almost justified Trump’s involvement in the strip.

Then? Nothing, for a while. Trump just disappeared for a while. More Mary Kay provocations occurred. Opus relearned tired lessons about consumerism, ran up huge phone bills via “Dial-a-Mom,” and published a memoir. Hodge-Podge and Rosebud mated and had a litter. A freshly dumped Steve Dallas reverted to the chauvinist pig he was before aliens scrambled his brain. Milquetoast the Cockroach continued to receive far, far too much attention.

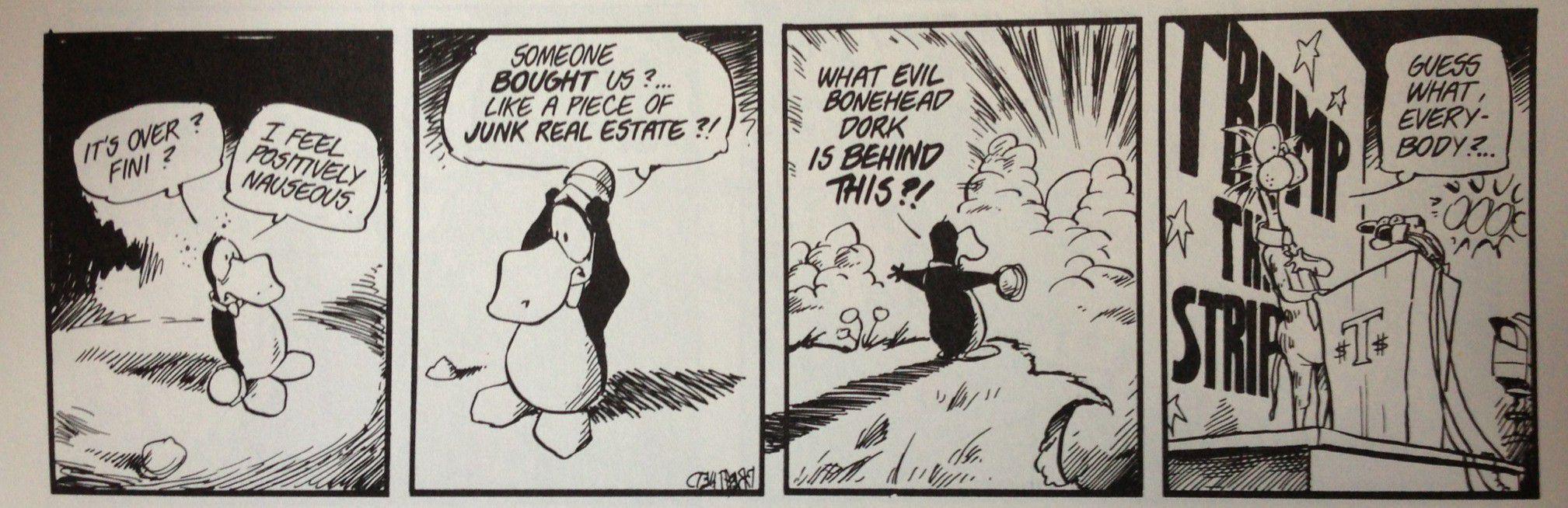

Then the shit hit the fan.

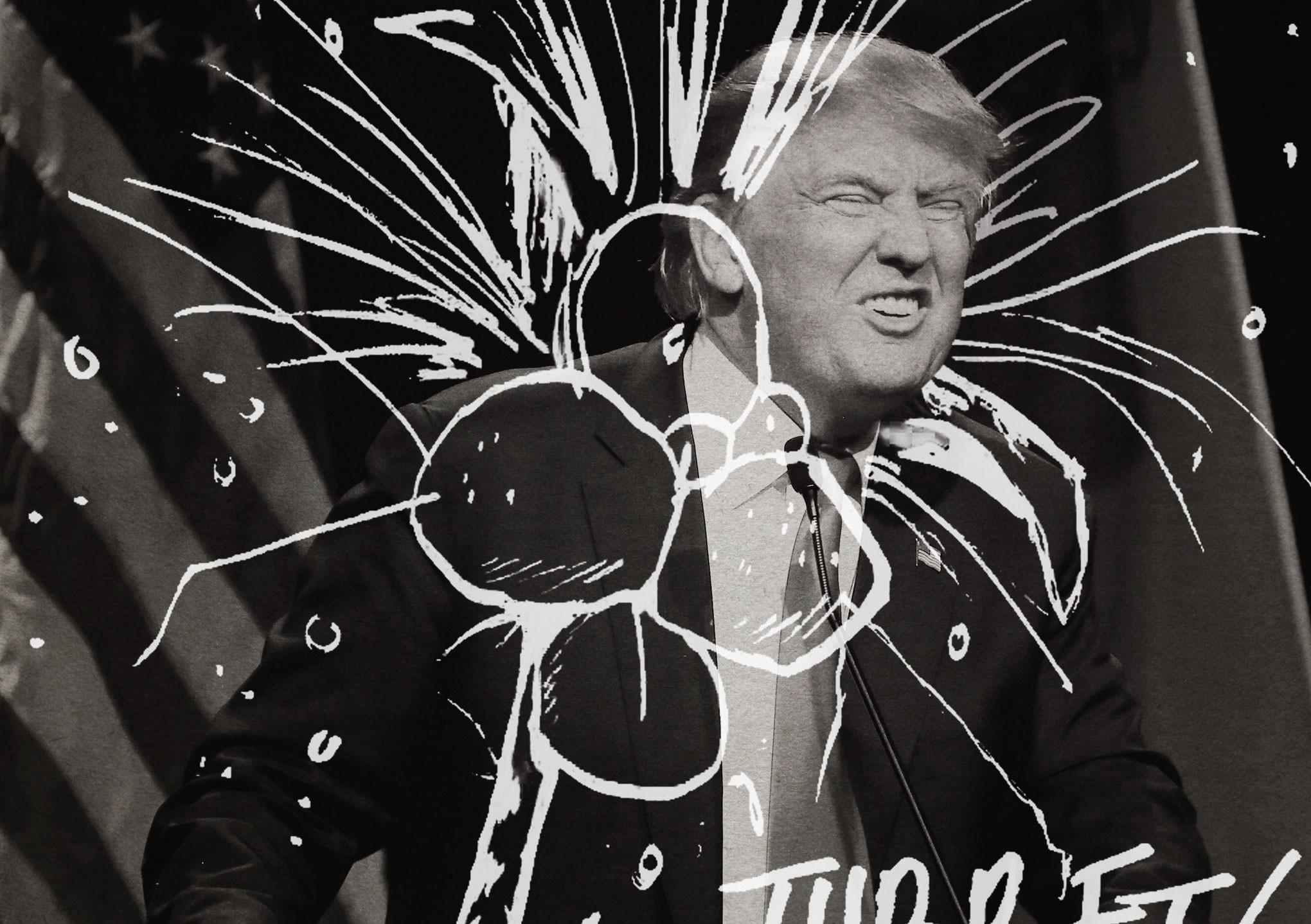

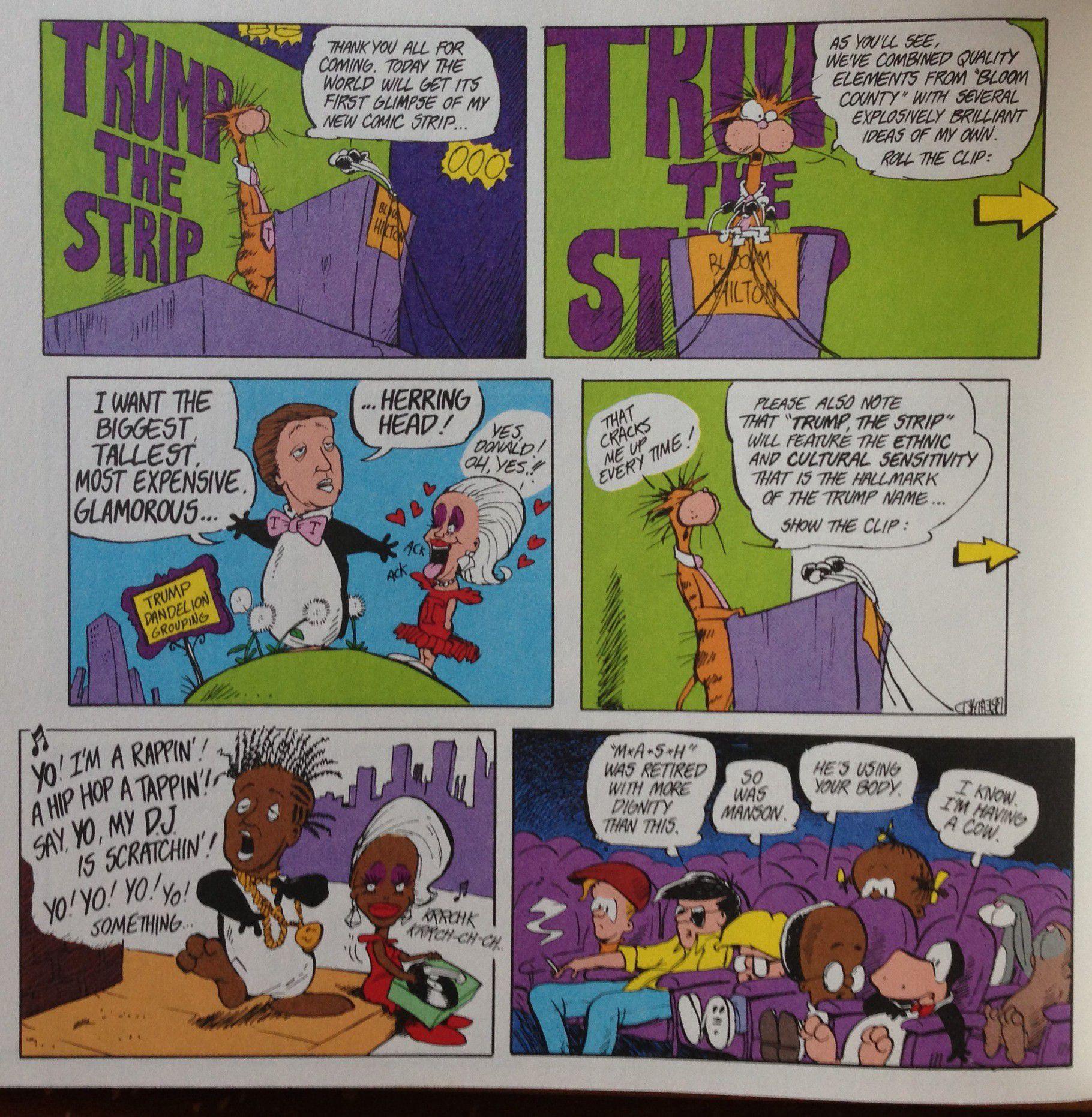

Bill-as-Trump purchases the strip, refashions it in his own image, and fires everyone. For the first time, Breathed renders Trump’s actual face, plastering it atop Opus’ penguin body in a full color Sunday strip. Here is Trump-as-Opus, rapping cluelessly on a street corner. There is Trump-as-Opus in a dandelion field — the Bloom County equivalent of a safe-space — demanding “the biggest, tallest, most expensive, glamorous … herring head!” Symbolically speaking, this was a graffiti tag on the “Mona Lisa”; literally speaking, it announced that Bloom County was ending.

But afterward, artistically, one could feel a weight lift from Breathed’s chest as he waded into the final, post-firing weeks of Bloom County: The laughs and gags came easier, as cast members sought new jobs in the comic strip and comic book industries. In this light, the Trump experiment could almost be viewed as a success. The strips themselves weren’t that fun to read, but by briefly evoking and exploiting Trump, Bloom County shook itself out of a rut while edging toward an earned and necessary exit. For certain funny pages readers, Bloom County was the hottest of commodities. Unwittingly and unwillingly, the Donald inspired a comedic uptick once the deal was done, and readers willing to hang in till the bitter end could take comfort in a few late-inning belly laughs. In that context, it’s not so surprising that Trump’s persona — still boorish, blustering, and aggressively superficial — would help resurrect the strip a quarter-century later. It’s a different world, and a different comic landscape, but the Donald, for better and mostly worse, is unchanged.

Raymond Cummings is a writer and critic living in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania. His work has appeared in Pitchfork, The Village Voice, Spin, and Splice Today; Vigilante Fluxus, his latest collection of poetry, was published last year.