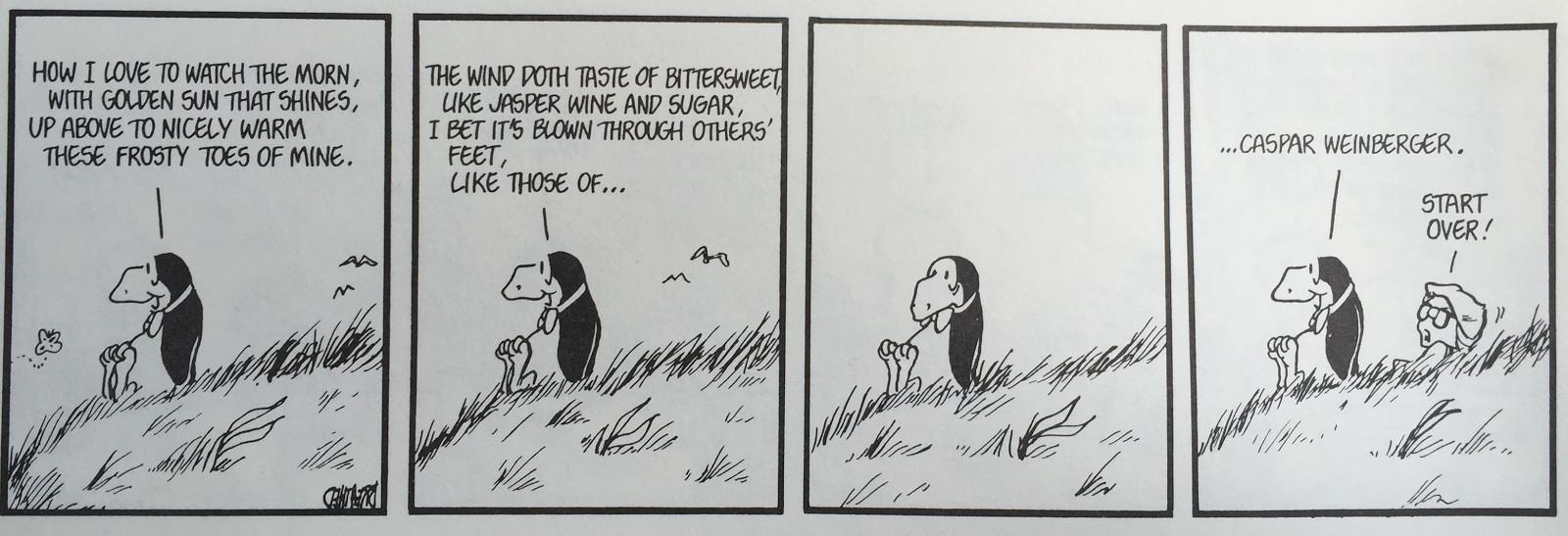

Caspar Weinberger was secretary of defense under Ronald Reagan for most of the 1980s; his taste for blockbuster military budgets served him well during the Cold War and less well during the Iran-Contra affair. But all that only obscures his true (and cosmically just) legacy: poetic Bloom County punch line.

Yes, to have Opus the Penguin — a comic-strip icon on the same God Level tier as Charlie Brown or Calvin — compose a poem in your honor in as many as 1,200 newspapers nationwide was a profound cultural honor in 1983. What would the modern equivalent even be? South Park? Kanye West’s George Tenet shout-out on “Clique”? (“You know white people!”) Weinberger knew enough to be flattered: He sent Bloom County author Berkeley Breathed an appreciative answer poem, on official Department of Defense stationary. Opening line: “Many a morn I’ve longed to see / A comic strip be kind to me.” That’s how reader feedback worked in the ’80s.

“What would the modern equivalent even be?” is a recurring problem with Bloom County, one of the greatest comic strips of all time and the single weirdest enormously popular cultural phenomenon of the Reagan era. The conceit was very simple, and very familiar — the random, whimsical, mildly tragicomic foibles of animals who act like humans, and humans who act like buffoons — but the execution was magnificent, and very peculiar. These weirdos were drawn so precisely that anyone could relate. Opus was an effete, lovelorn, herring-guts-munching schlub, uncool and unheroic even for flightless waterfowl. He had no solutions for society’s ills — just galactically twee coping mechanisms.

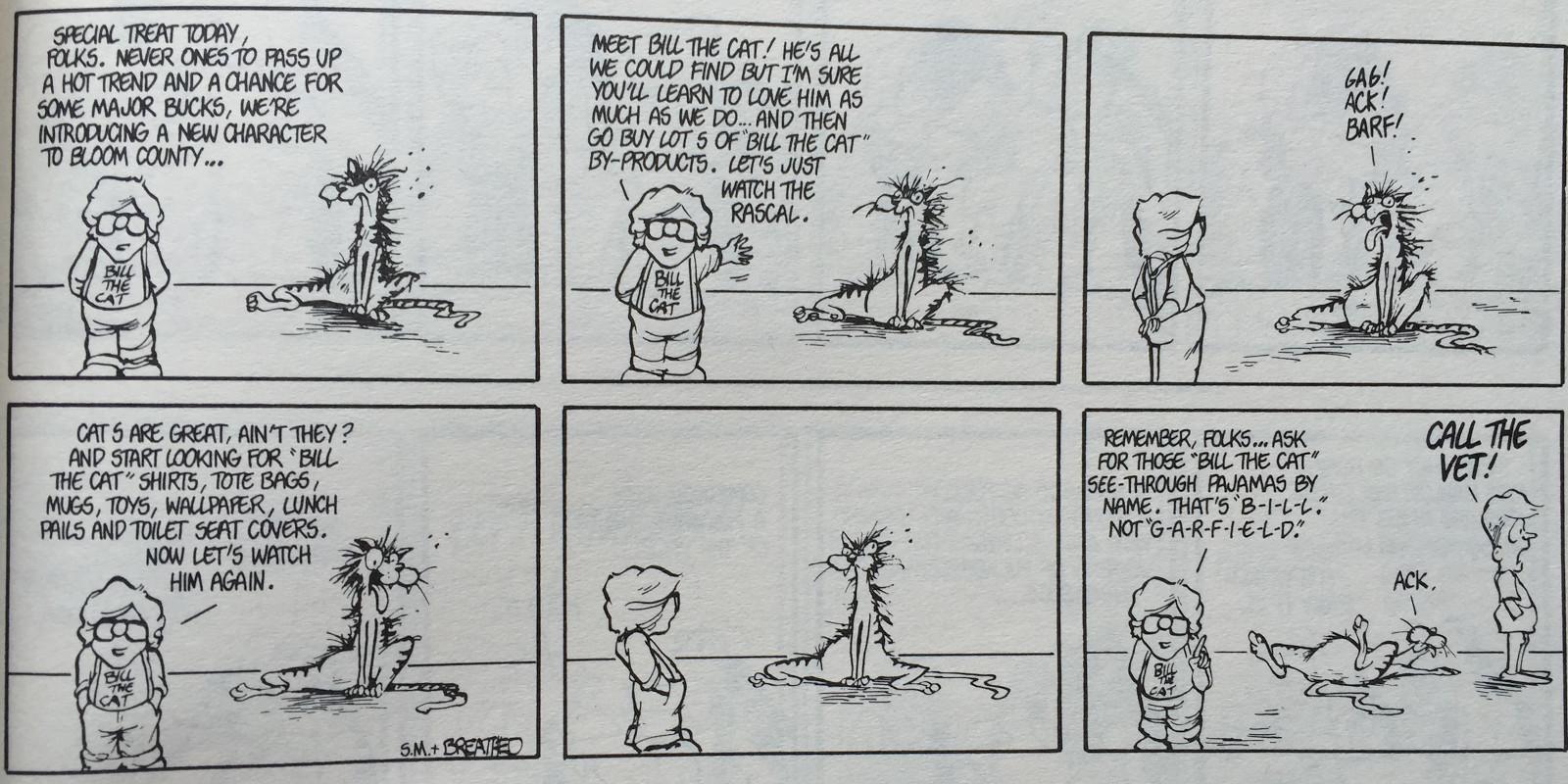

Which, naturally, made him a merchandising coup anyway: plush dolls, coffee mugs, T-shirts, suction-cup car-window caddies, Christmas ornaments, even screen savers when that became a thing. His personal Scottie Pippen was Bill the Cat, a scuzzy, hedonistic, oft-catatonic, and occasionally dead furball who ran for president twice, fronted his own heavy metal band (Billy and the Boingers) by strumming on his tongue, and carried on a torrid affair with hard-nosed U.N. ambassador Jeane Kirkpatrick, another real-life person I know about only because of this comic strip. Bill sold a ton of real-world merch, too, despite being introduced specifically to razz Garfield for doing the same thing. That’s how self-loathing capitalism worked in the ’80s.

The strip started in 1980, netted its author the Pulitzer Prize for editorial cartooning in 1987 (“real” editorial cartoonists were super-pissed), and ended in 1989. (The whole thing wrapped up, notably, with a story arc in which Donald Trump — then just an über-rich, egomaniacal buffoon of no greater societal importance — buys the rights to the strip, fires most of the characters, and rebrands the whole thing as Trump the Strip.) Breathed did a couple Sundays-only spinoffs: Outland launched in Bloom County’s wake and ran until ’95, and Opus followed from 2003 to 2008. But the strip’s original ’80s run is singularly revered, and stands now as a bizarre combination of dated (Jeane Kirkpatrick?) and timeless, as vital a monument to comic strips in their indomitable print-media prime as Calvin and Hobbes or The Far Side or Peanuts.

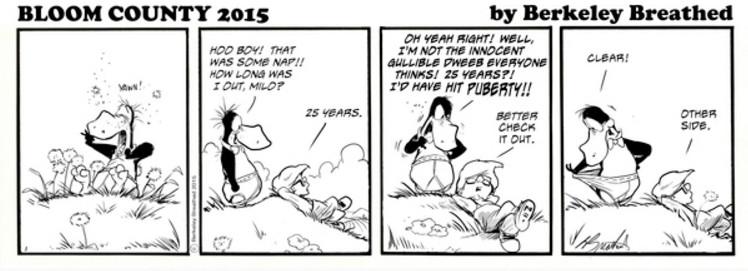

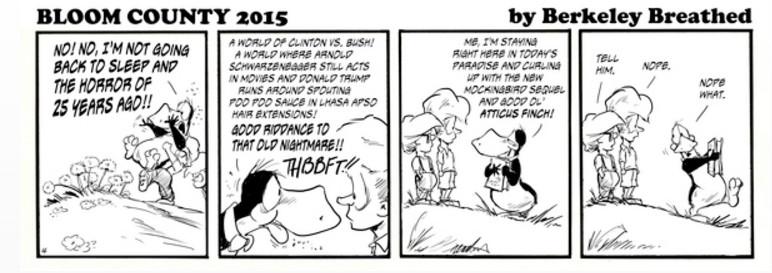

And now it’s back. On Facebook. Breathed relaunched the strip in July of last year, coyly half-acknowledging that Trump’s political ascent goaded him into action. But is he here to ride that wave, or help push it back into the sea? How unnerving is it to see one of the most beloved ensembles in cartoon history, emblematic of an era now three decades past, cracking Game of Thrones jokes about the 2016 election on the world’s biggest social media platform? It seems impossible to explain any of this to someone who wasn’t around to enjoy it in real time; it feels somehow vitally important to try. Because no man — and no penguin — is better equipped to actually make America great again.

Start with his name, so perfect for a sardonic, liberal-leaning native Californian who distrusted empires but built one of his own anyway: Berkeley Breathed. He was born in Encino but raised in Houston, and as he told NPR last year, he mostly pulled Bloom County’s strings from the lonely Midwest: “I wrote every single cartoon strip in isolation in a dining room in an Iowa City farmhouse.” In the mid-2000s, I saw Breathed do a reading at a San Francisco bookstore to promote one of his post–Bloom County children’s books, and he regaled us with old tales of deadline anxiety so acute he’d find himself driving his newest strips to the airport in the dead of night to get them on a plane out to his editors in Washington, D.C. Sometimes he’d even buy a ticket and physically get on the plane himself just to have a few more precious hours to draw them. He was exactly the sort of neurotic secret-workhorse slacker bohemian who generally knocks ’em dead at bookstores in San Francisco.

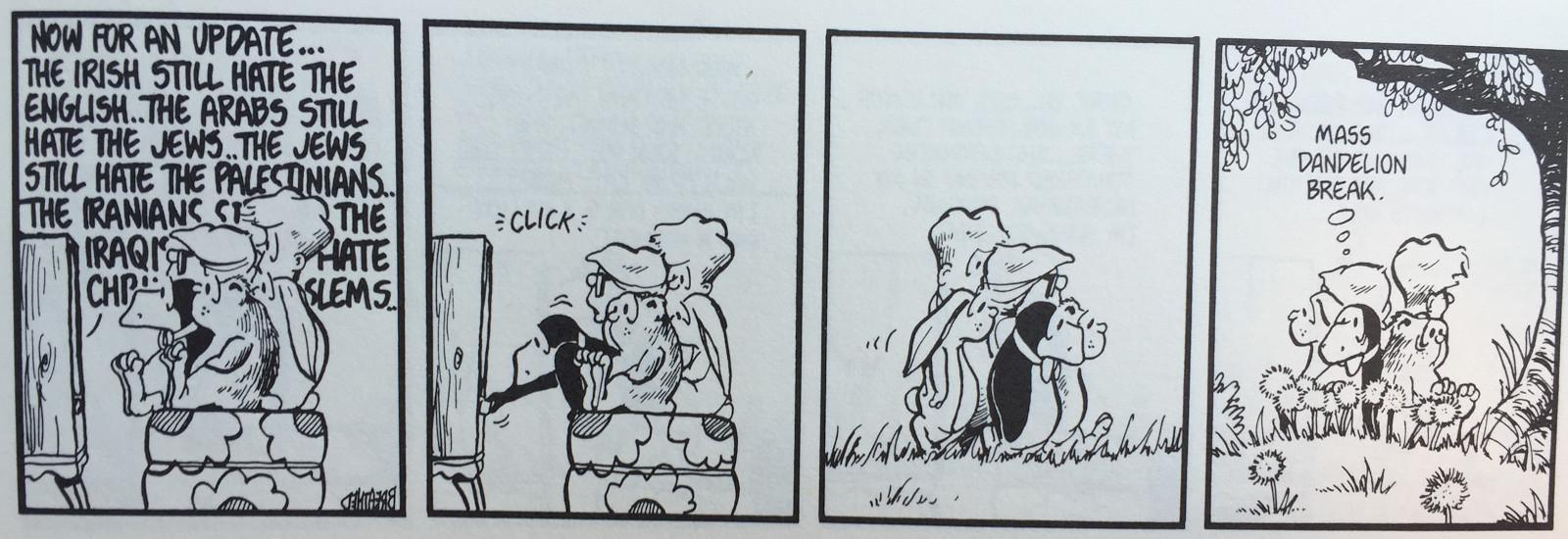

That one’s from 1983, just FYI; add “BLACK LIVES MATTER!” and swap out “SOCIALIZED MEDICINE!” for “OBAMACARE!” and it could’ve run in yesterday’s paper. In terms of the plot or the premise or even the point, it’s best to think of the strip as Breathed inventing a random gang of outcasts just to keep him company at that dining-room table. Bloom County’s hub is a mostly unspecified small-town boardinghouse; the little dude up there with the glasses is Milo, a 10-year-old bulldog political reporter who started out as the main character, before Opus and Bill emerged as the breakout stars.

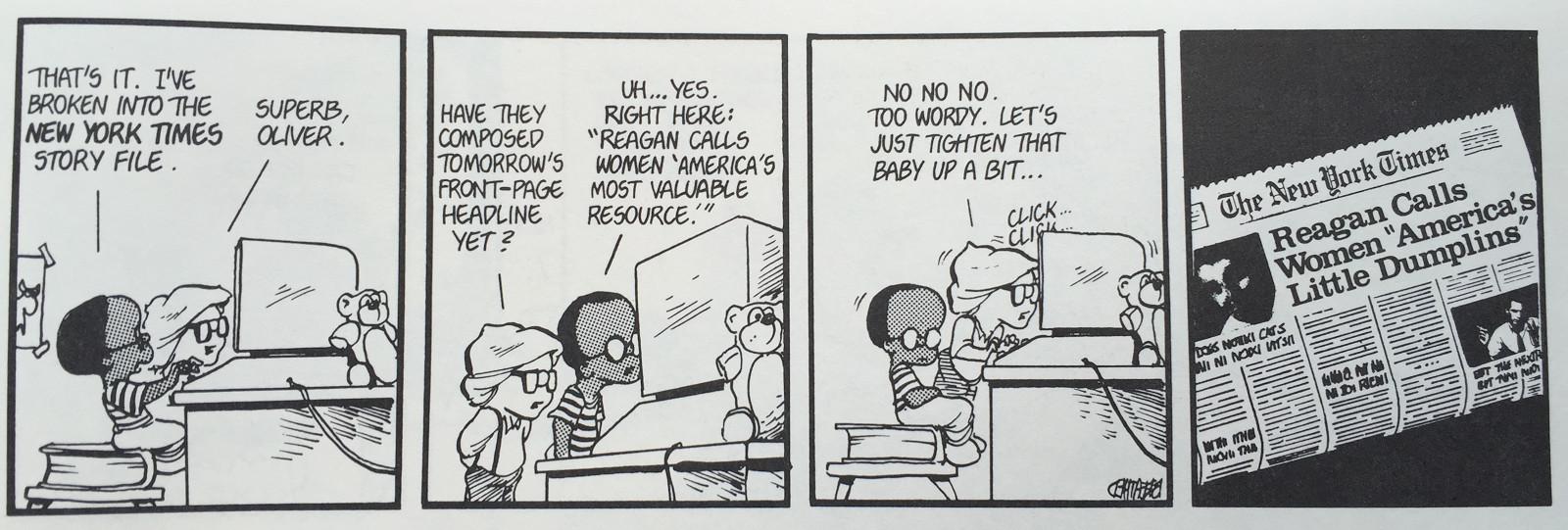

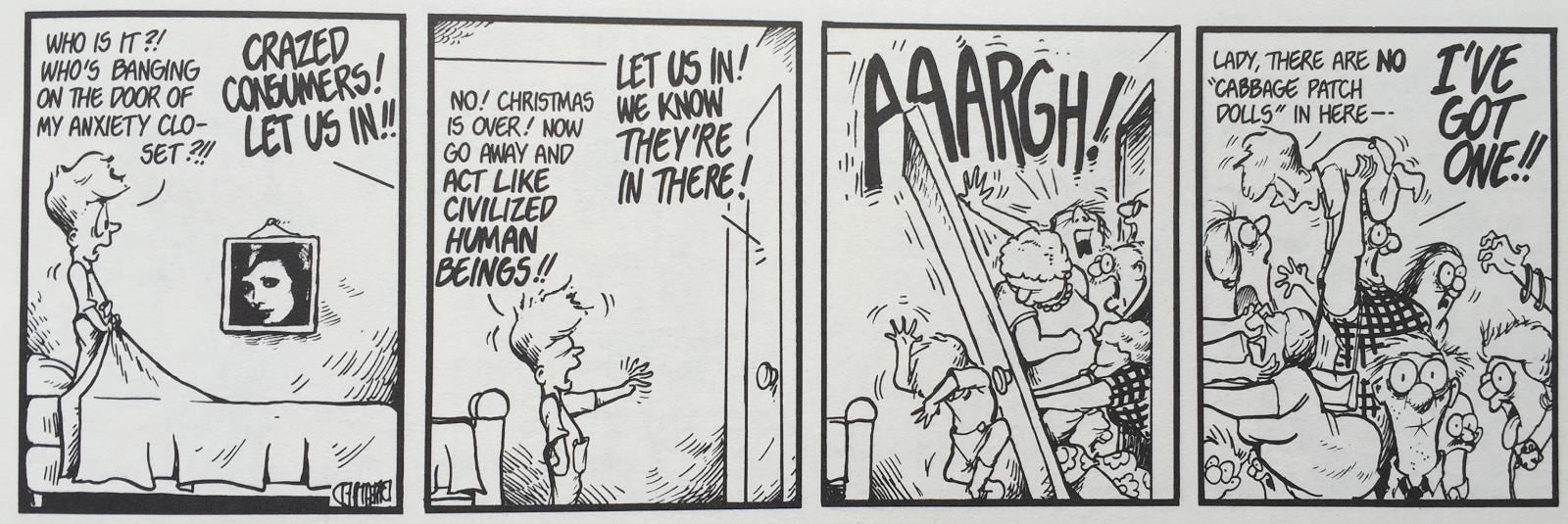

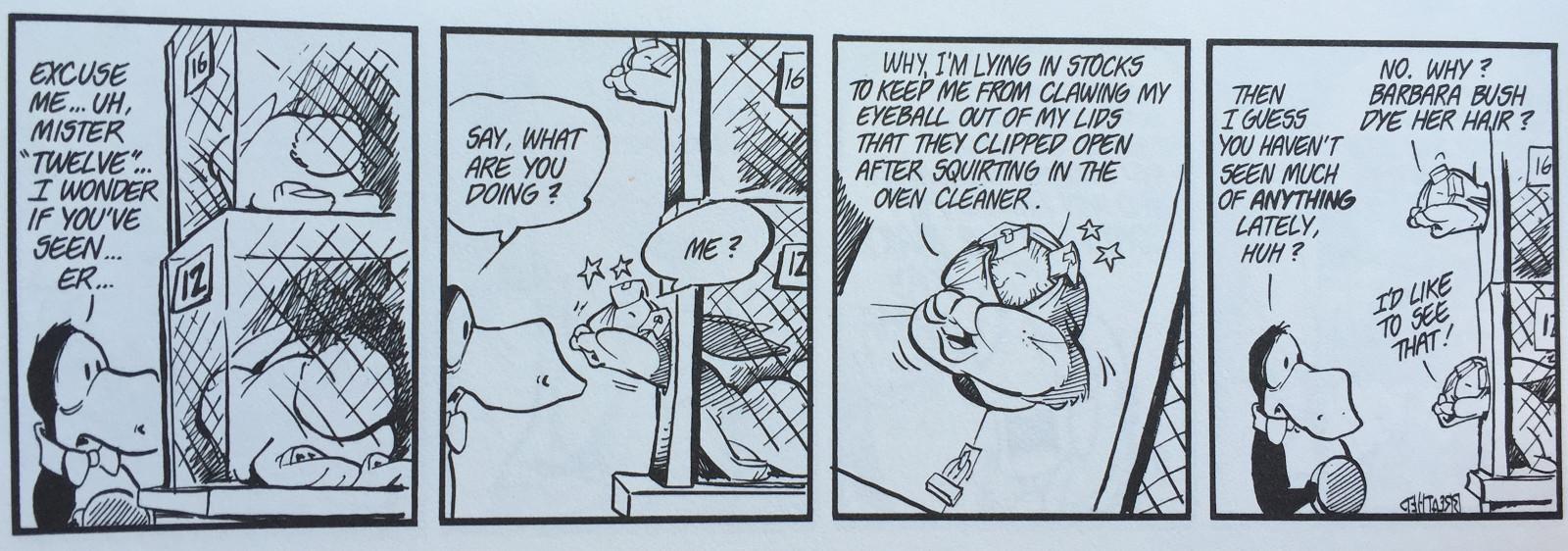

Oliver Wendell Jones is the science geek and computer hacker: He starts out on an IBM but soon graduates to a “Banana Junior 6000.” (His parents disapprove and keep trying to goad him into idolizing Michael Jackson, oof.) The other little kid is Binkley, a jittery celebrity enthusiast with amazing hair whose lasting contribution to society is his Anxiety Closet, which menaces him at night with, among many other terrors, giant snakes, macroeconomists, an ax-wielding librarian, feuding political commentators, his failed future adult self, and the first girl he’ll ever kiss (who is so traumatized she ends up joining “a lesbian terror group”).

The animals are rounded out by a misanthropic groundhog, a lethargic basselope, and a rabbit who splits the difference; together, they’re like a deranged Mad magazine inversion of Winnie the Pooh’s crew. (Presumably, comic-strip artists love talking animals simply because they get tired of drawing people. That, and the whole merchandising thing.) Most of those little guys spend most of their time with Cutter John, a wheelchair-flaunting Vietnam vet who’s big into Star Trek and smooching with various ladies in the meadow. (Just smooching — this ran in family newspapers, remember.)

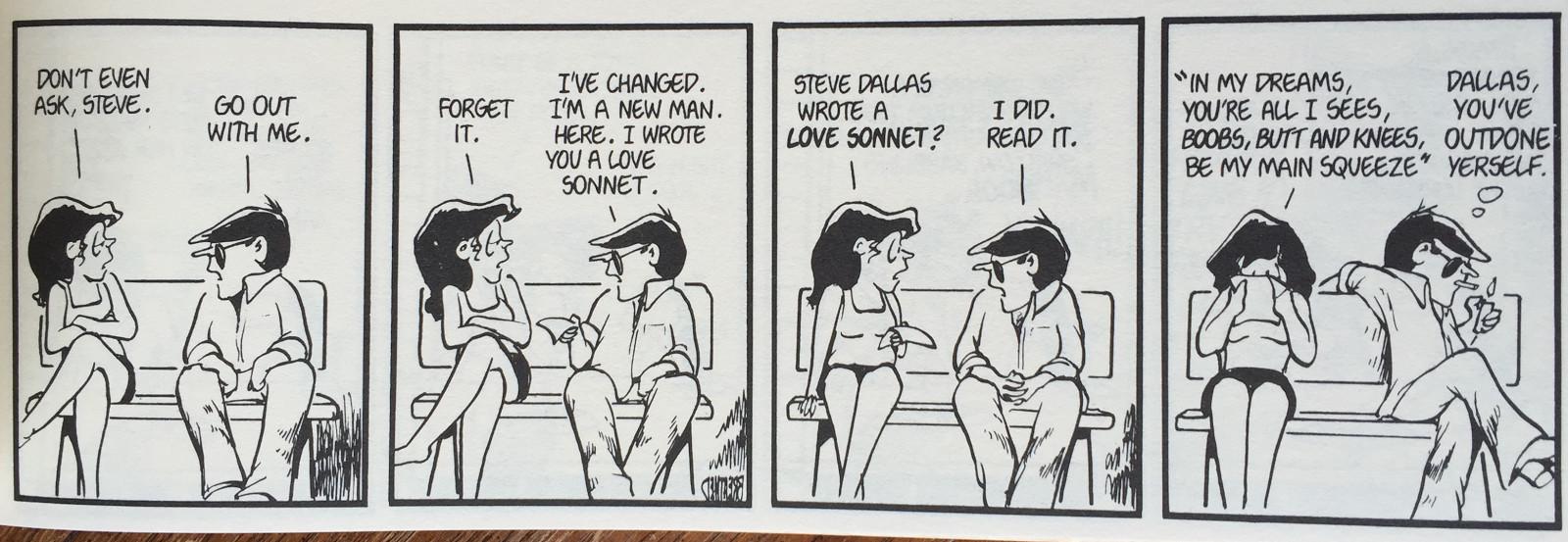

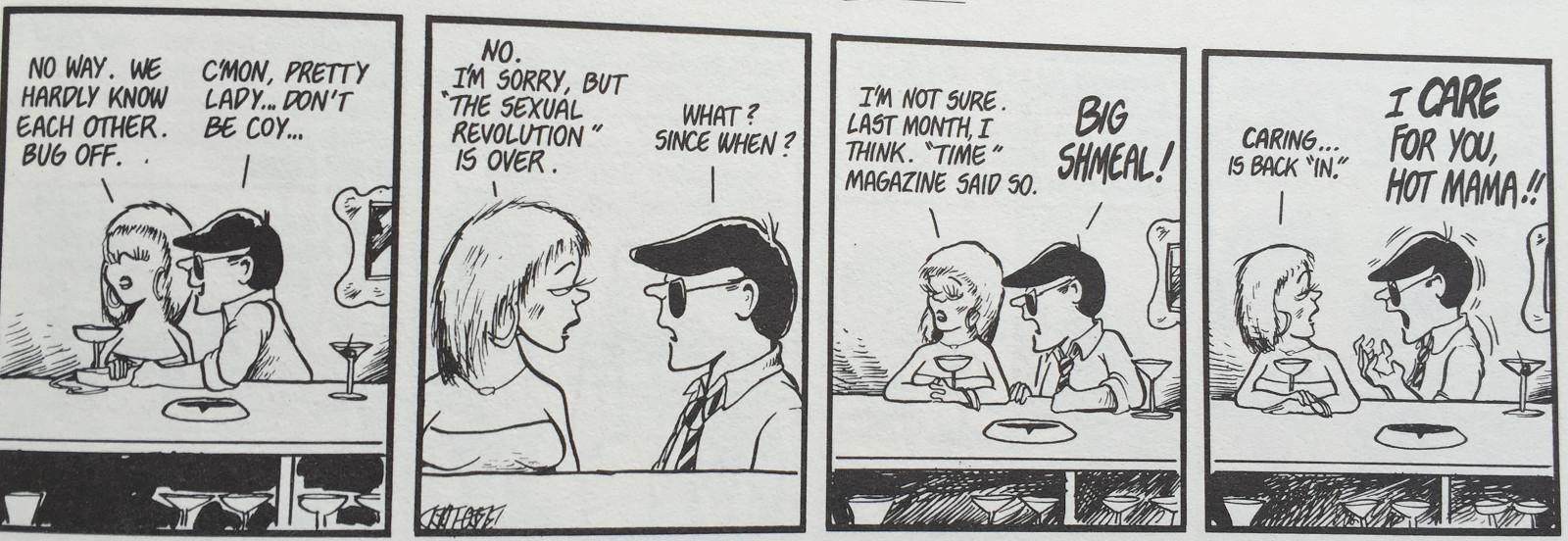

Finally, there is Steve Dallas, the dirtbag lawyer and inept womanizer who is, in his own delightfully pitiful way, Bloom County’s best character by far. The second-best character is the cigarette perpetually dangling out of his mouth.

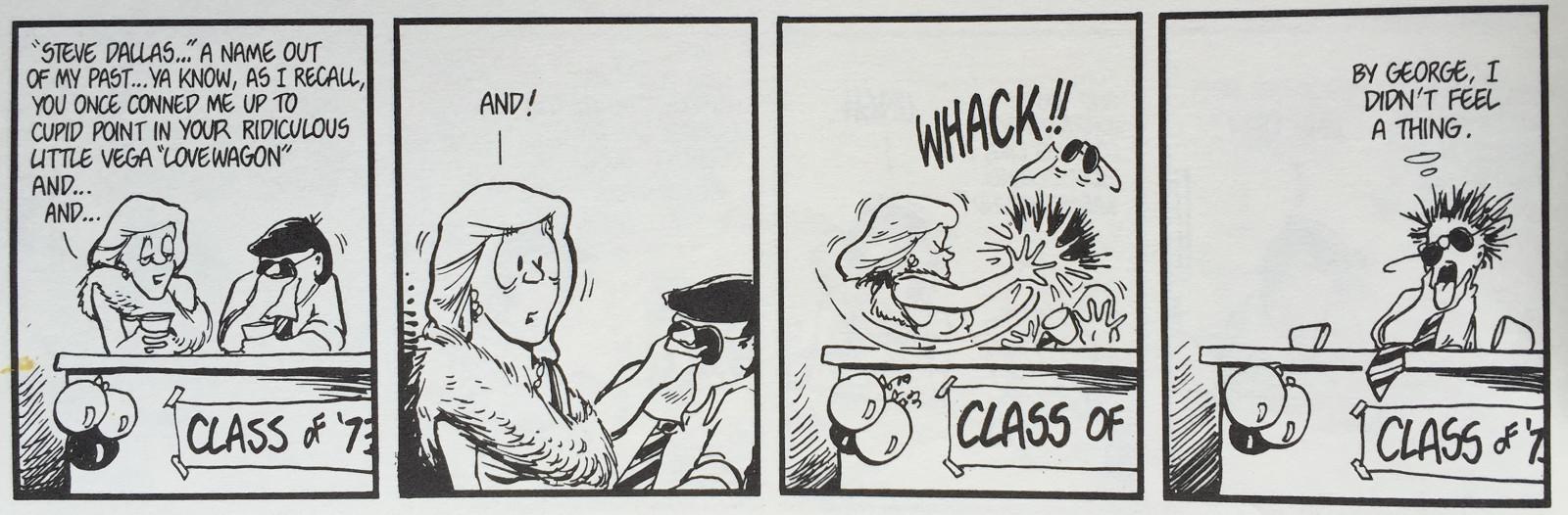

With the cigarette especially, Steve Dallas bears a striking resemblance to Andy Capp, the ’50s-born English comics superstar whose eponymous adventures ran right alongside Bloom County, and in fact continue to this day, despite even Homer Simpson once correctly identifying Andy as a “wife-beating drunk.” (In the “Marge vs. the Monorail” episode, no less.) My grandfather used to let me read his Andy Capp anthologies when I was a kid; they taught me that marriage involved a lot of miserable grousing punctuated by the wife punching the husband right out of the panel with a whimsical “BOP,” if not the other way around.) Steve is an uncouth but harmless teddy bear by comparison, but there’s still a distinct unease now in realizing that the fourth panel here (he’s at his high school reunion, straight from the dentist, who left his mouth completely numb) is my all-time favorite Bloom County image.

Steve gets slapped by a woman (Breathed prefers “WHACK!” or “WACKO!”) five times in the first Bloom County anthology, 1983’s Loose Tails, alone; later, he is hospitalized in a paparazzi mishap by a raging Sean Penn, which is cosmic justice of a sort. Climactically, late in the decade, Dallas gets abducted by aliens and submits to an enlightened, tobacco-free New Age makeover that makes him look like Steve Guttenberg, but it’s likely Breathed wasn’t atoning so much as satirizing the impulse to atone. Nor does it help that this strip has very few female characters who aren’t just exasperated love interests with names like Quiche Lorraine, Lola Granola, and Yaz Pistachio.

Will I nonetheless yell, “I CARE FOR YOU, HOT MAMA!!” at my wife sometime in the next week? Who can say? The fraught aging process, for good and ill, is part of the deal here. Comic strips are designed to be atemporal — characters rarely grow up and current events rarely intrude, with a few notable exceptions — which allows the likes of Blondie, Dennis the Menace, and The Family Circus to flourish with new authors long after their creators’ deaths. (Best-case scenario there is that the new author is the original author’s son.)

Bloom County is having none of that. It is a stubborn product of its time: It’s fun to imagine, say, all the characters on The Americans reading it over their Cheerios. The plots were only occasionally super-topical — Santa’s elves going on strike à la air-traffic controllers, George Lucas’s unacceptable Star Wars sequel timeline, a Republican-dominated presidential election or two — but the name drops were another matter entirely. To revisit the original run now is to be inundated by a torrent of references that might still resonate for you, and might, uh, not. Tip O’Neill … Ed Meese … Benji … Al Haig … Philip Habib … Jimmy Hoffa … Carl Sagan … Marlin Perkins … Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh … guys (and dogs) like that. Breathed clearly distrusted mass-market pop culture — musically, he was clearly not a heavy metal fan — and he tended to gravitate toward assorted Reagan cronies and/or cabinet members instead. And not even to mock those people, exactly — just to revel in the absurdly stiff sound of their names. Though who doesn’t love a good Spuds MacKenzie joke.

The easiest way to read the strip now is to snag the used anthologies off Amazon, often for $.01 (plus shipping and handling!) apiece. (Or, you could just rifle through the books stacked up on the toilet tanks of your coolest aunts and uncles.) If you’re going in mostly blind, the best stand-alone volume might be 1989’s The Night of the Mary Kay Commandos, which, yes, has plenty of Michael Dukakis jokes, but also an eerie sequence in which Opus tries to free his long-estranged mother from a Mary Kay facility, triggering a handful of disturbing images that helped shame the cosmetics company into declaring an animal-testing moratorium soon thereafter.

One very crucial thing you lose with the books, unfortunately, is the sheer anarchic dissonance of reading a strip that raw in its natural habitat, i.e., the comics page of your hometown newspaper, alongside Ziggy and Marmaduke and Beetle Bailey and the Wizard of Id and Funky Winkerbean and Hagar the Horrible. You can’t quite grasp the utter delicious subversion of Bloom County without a thorough understanding of what, exactly, it was subverting. Breathed’s humor was rarely mean-spirited, but he loved using typical broad comic-strip beats as the means to obscure, befuddling ends. He was a class clown with the heart of a wonk, or vice versa; he was playing chess while all his competitors played checkers (though they all also played Monopoly). Of course, hunt down a newspaper comics section today and all those old, tired zombie strips are still shuffling around, but that ain’t where the action is anymore. Which brings us — and brought Berkeley Breathed — to Facebook.

Few comic-strip creators ever truly qualified as superstars, even back when this turf was truly hallowed ground. There was Doonesbury’s Garry Trudeau, who got a decade’s head-start (and won his own Pulitzer in 1975), but had a far less surreal (no penguins!) and far more explicitly political approach. There was Peanuts’ Charles Schulz, who got his own museum and his own loving but alarmingly grim biography, which suggested that Charlie Brown’s winsome misery was mostly autobiographical. And then, in 1985, came Calvin and Hobbes’s reclusive Bill Watterson, probably the single most beloved figure in his field, in part because he left ’em wanting more, closing down the strip in its 1995 prime and refusing to ever green-light the cynical merchandising spree that Breathed mocked but couldn’t quite resist. (The Pissing Calvin phenomenon was, to say the least, extremely unauthorized.)

Bill inspired his own full-length documentary, the loving and not nearly as grim Dear Mr. Watterson, in 2013, and in it, as perhaps the most prominent reverential talking head, you’ll get a rare-in-its-own-right glimpse of Berkeley Breathed. There’s our guy, staring down the camera, making his sheepish confession: “I was making these [dramatically throws down Bill the Cat doll], and he was not.”

Any hint of a return from Watterson throws a very specific corner of the internet into a frenzy (he randomly hijacked the strip Pearls Before Swine for a few days in 2014), but Breathed has never quite gone full recluse. (Alas, most recently, a 2011 Disney movie based on his 2007 children’s book Mars Needs Moms! was a massive flop.) It was a pleasant surprise but hardly a shock when he first relaunched Bloom County in July 2015, but with no apologies to Trump, few might’ve guessed the single human most responsible for goading him back into action: Harper Lee.

Maycomb, the fictional small Alabama town in To Kill a Mockingbird, had a huge effect on a young Breathed, and eventually inspired Bloom County itself; likewise, last year’s icky publication of Lee’s controversial Mockingbird sequel Go Set a Watchman clearly shook him up. As he told NPR: “I watched slack-jawed in horror as they threw one of the 20th century’s most iconic fictional heroes, Atticus Finch, under the bus.” What’s more, Lee herself had written Breathed a fan letter, self-identifying as “a dotty old lady” with a simple plea: “Please don’t shut down Opus. Can’t you at least give him a reprieve?”

The lesson: If Breathed didn’t give Opus his own modern iteration, someone else might. The late 20th century had Pissing Calvin; the early 21st century has Crying Jordan. The internet, and the wider content industry in general, does whatever it wants now with the past’s cultural flotsam, and if you don’t take control of it yourself, you take your chances. So here we are.

Is the new Bloom County weird? Most definitely. (Facebook is the main hub now, though GoComics is the easiest way to breeze through the whole archive.) A very early new strip showed Opus moping as his dear old friends all stared at their iPads and iPhones, and the effect was viscerally, enormously upsetting. These people (and animals) don’t belong here. They’re too good, too pure. Most of the uneasy thrill so far lies in such anachronisms, watching ’80s icons make grandpa jokes about Kim Kardashian or Jennifer Lawrence or Carly Fiorina. (Breathed, or someone very important to him, seems to be really into yoga.) Did the ’80s strip’s potshots at Madonna and The Love Boat sound as forced at the time as all these cracks now about man buns and safe spaces and Apple Watches and red holiday Starbucks cups and Harambe the Gorilla? Probably! Being a crotchety old soul has always been this guy’s M.O. Let him live.

As always, context matters. It’s jarring first and foremost to see Steve Dallas looming in between your friends’ and cousins’ and mortal enemies’ status updates: It’s a very literal representation of how hard a content creator has to work now to get any attention at all. The new strip has the same hangups as the old — we’ve got a new cast of female love interests, including one named “Cozy Fillerup” — but the charms are there, too. It’s worth it, really, just to watch Breathed struggle with how to handle 2016 Donald Trump: He’s got the same issues trying to satirize the presumptive Republican presidential nominee as the rest of us, but he keeps trying. The running thread where Binkley’s crotchety old father comes to grips with being a reluctant Trump supporter is the most promising.

After a full year, the new Bloom County isn’t yet great, but it’s comforting, and expecting it to recapture the strip’s old glories straightaway is to misunderstand how complex and singular and now-remote an environment it truly was, back when those old glories were new. And regardless, “Berkeley Breathed slowly makes sense of the internet” is a fascinating, totally worthwhile long-term endeavor. The internet, after all, in its own discordant way, is still making sense of him.

You want a road map, and a best-case scenario? Try Chris Onstad’s phenomenal web-only comic strip Achewood, which launched in 2001, sells a few books and T-shirts itself, and has a distinctly familiar mix of anthropomorphic-animal whimsy and disruptive melancholy. (Start here, and don’t stop until you’re done.) Opus’s spiritual disciple is a depressed skater-argot-fluent cat named Roast Beef; email me and I will provide the full Bloom County–to-Achewood-character decoder ring. I’m serious. It’s uncanny. What Breathed has learned in the past year is that people still care that much about him, and that there are still people out there as crazy as he is. It’s a joy simply to geek out like this again, to watch a spry relic of an ever-distant past finally grapple with what the modern equivalent might really be. May the Caspar Weinbergers of our time prove just as grateful.