Any day now — maybe tonight, maybe by the end of the weekend — we’ll witness the capstone of Ichiro Suzuki’s career-spanning sizzle reel. In the footage of the milestone, he’ll forever be on base, gray-haired but still willowy from the waist up, smiling and holding his helmet aloft as a message on the stadium’s video screen reminds the crowd to cheer for the future Hall of Famer’s 3,000th MLB hit (and 4,278th as a professional, including his years in Japan). No one will be sorry to see this, except possibly Pete Rose. We haven’t put any polls in the field, but it’s hard to imagine any player having a higher public approval rating than Ichiro, who’s as singular in civilian clothes as he is unique in uniform.

Suzuki is just three hits away from that next round number. After slumming (and slumping) in lower lineup slots for the past few seasons, the 42-year-old’s leadoff status has been restored in 2016, less out of deference to his status as baseball’s oldest position player than out of recognition of his well-preserved skills. Resting regularly to stay fresh, Ichiro is swinging and striking out less often than ever, posting baseball’s best walk-to-strikeout ratio among players with at least 200 plate appearances. He still plays above-average defense, still steals bases efficiently, still flies down the line. And although he doesn’t hit the ball hard, he’s batting .365 when he puts it in play, which we might say is unsustainable if he hadn’t beaten that mark before — four times.

For a player who’ll probably make it into Cooperstown on his first ballot — which will set up his seventh trip to the shrine — Ichiro inspires an unusual number of what-if exercises. Prime among them is the question of how many hits he would have if he’d debuted in the big leagues earlier. Although Ichiro faced a lower level of competition in Japan, this riddle is relatively easy to answer. He was essentially the same player from his first full season in Japan through his last — his OPS at age 20 was only five points lower than his OPS at age 26 — and his batting average over his last three years in Japan was just 12 points higher than it was in his first year in Seattle. Combine those two tidbits with the fact that the major league schedule is significantly longer than the one Ichiro played in Japan, and it’s reasonable to assume that he’d have just as many hits, if not more, had he been a big leaguer from day one — which would have made him the all-time MLB hit king (much to Rose’s chagrin).

The other what-if isn’t so simple: Could the ground-ball-oriented Ichiro (who still hasn’t homered this season) have hit for power? And if he had hit for power, would his teams have been better off?

Over Ichiro’s 10-season prime (2001 to 2010), he was the fourth-best player in baseball, behind Albert Pujols, Alex Rodriguez, and Barry Bonds (who played in only seven of those seasons). Normally, that wouldn’t leave much room to find fault. As a legion of spoilsport sabermetricians have observed, though, Ichiro’s eye-catching batting averages were on the empty side, unaccompanied by much patience or power. Over the same peak period, Ichiro’s offensive value (baserunning included) ranked 22nd, behind luminaries such as J.D. Drew and Derrek Lee. And on a per-plate-appearance basis, Ichiro’s offensive output ranked 59th, behind Cliff Floyd, Erubiel Durazo, and Nick Johnson. Statistically speaking, Ichiro’s high averages weren’t what made him an all-timer; based on his contributions in the batter’s box, he wasn’t worth that much more than many other names you know. The key was combining his hitting style with his defense, his durability — he lost zero time to injury until a 2009 ulcer and calf strain — and his leadoff spot, which generated lots of plate appearances.

Odds are that Ichiro’s 3,000th major league hit — like his first and his 1,000th — will be a single; only 15 percent of his hits this season have gone for extra bases. We know, though, that there’s more oomph in there. As ESPN’s Tommy Tomlinson wrote in a recent profile, “In batting practice, Ichiro is the Babe. He parks pitch after pitch into the right-field stands. A few land in the upper deck.” That description came on the heels of an endorsement from Marlins hitting coach Barry Bonds, who became the latest in a long line of awed observers who’ve claimed that Ichiro could win the Home Run Derby if he wanted to. Tomlinson also tells a tantalizing story from Ichiro’s first spring training, when Mariners manager Lou Piniella, doubting the efficacy of Ichiro’s slappy approach, told him to pull the ball. The next time up, Tomlinson says, Ichiro “jacked a home run into the right-field bullpen.” It was the spiritual sequel to the time Ty Cobb successfully swung for the fences for a single series, just to prove a point.

Ichiro gave the already-rampant speculation legs in 2007, when he made a statement that statheads could cling to: “If I’m allowed to hit .220, I could probably hit 40 (homers), but nobody wants that,” he said. When I first heard his claim, I was skeptical that a star player could completely reinvent himself after making the majors. Now I’m not so sure. Zack Cozart went from the worst hitter in baseball to an above-average one because Barry Larkin casually suggested he swing harder. Mets hitting coach Kevin Long helped make Daniel Murphy into a monster by reprogramming him from “a guy seeking base hits to a guy seeking to do damage.” Deciding to throw more splitters has made optioned-to-Triple-A Matt Shoemaker look like a Cy Young contender for his past 12 starts. If lesser beings can pull off those apparent impossibilities, then maybe Ichiro really could have done a convincing impression of a power hitter. After all, Adrián González homered immediately when he stole Ichiro’s swing.

So let’s imagine that Ichiro, a hitter whose whole career has hinged on his ability to beat out infield hits and aim baseballs just beyond the nearest fielder’s range, had realized that the easiest way to do that would be to flick them over the fence. Let’s also stipulate that he was capable of putting that plan into practice. Would he have been better or worse?

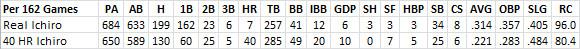

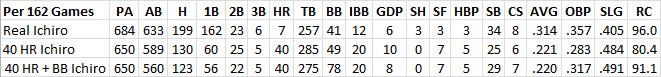

To find out, I used Bill James’s “technical” formula for Runs Created to estimate Ichiro’s offensive run value in two alternate realities: one in which he hits 40 homers, and one in which he hits 40 homers and also doubles his unintentional walk rate. “Real Ichiro” keeps his career averages, prorated to 162 games. For the hypothetical Ichiros, I locked in 40 dingers and a .220 average (just as the actual Ichiro ordered), then assigned additional totals that seemed to make the most sense, relying on some assumptions about how morphing into the second coming of Dave Kingman might affect Ichiro’s overall line.

If Ichiro had turned into a slugger, then like most sluggers he probably would have hit in the heart of the order. So because he doesn’t bat first, 40-homer Ichiro makes fewer plate appearances. He also gets intentionally walked and hit by pitches slightly more often, because pitchers are afraid of his power. He doesn’t bunt, and he grounds into a few more double plays, because he has more men on when he comes to the plate. Mostly, he hits many fewer singles and many more home runs. And because he’s on base less often, his stolen-base totals decline.

The verdict? Forty-homer Ichiro is way worse than the real thing, more likely to make pitchers pay for mistakes but also much more exploitable (like Mark Reynolds or Chris Carter). Although he produces more total bases, the OBP loss hurts more than the slugging gain helps, and being on base less often limits his opportunities to steal.

But what if he walks? The actual Ichiro, who’s not too particular about the type of contact he makes, has typically posted below-average walk rates. But the 40-homer edition would draw more free passes, both because he’d be looking for pitches he could drive and because pitchers would have more incentive to stay away from his strike zone.

The powerful version of Ichiro who’s also willing to walk is … still worse than the version who almost always hits singles. The takeaway: It’s hard to hit .220 and be better than you are when you hit well over .300. And if you’re Ichiro, it’s hard to hit 40 homers without also hitting .220 (at least according to Ichiro, who should know). Ichiro is probably better off hitting the way he prefers to hit: the way he always has. A cursory 2010 Hardball Times study provides further corroboration, using linear weights to arrive at a similar conclusion: Even statistically (let alone aesthetically), reinventing Ichiro never made that much sense.

It probably seems unnecessarily nitpicky to fixate on the weaknesses — if you can call them that — of a player who does so many things well. In my mind, though, the constant questions about Ichiro’s power aren’t insults; they’re incredible compliments. No one asks whether Ben Revere should hit homers, because no one thinks he could. But Ichiro’s excellence seems so effortless that we can’t imagine anything on a baseball field being beyond him. He’s The Wizard, and we expect a wizard to be able to alter his appearance with a wave of his wand.

If Ichiro is right about how hitting for power would hurt his average, then we can probably put the thought exercise to rest. And good riddance: The real Ichiro — or “Ichiro!,” as U.S.S. Mariner’s Derek Zumsteg dubbed him — is vastly more entertaining than a lookalike who wouldn’t put balls in play. As Ichiro said, nobody wants that. Why would we tamper with someone who still makes us want to reach for our phones to tell the world what we saw?