For more than 100 years, it’s been common knowledge that hitters, as a rule, perform worse against same-handed pitching. Hence the inventions of switch hitting, and later, platooning.

Platooning is a tough act to pull off in an era when teams are using most of their bench space on relief pitchers, but in 2016, Cleveland has given its hitters the platoon advantage 70 percent of the time, the most in baseball. Meanwhile, the Toronto Blue Jays had the platoon advantage only 40 percent of the time, tied for the second-lowest mark in baseball.

This year’s ALCS presents a study in two contradictory answers to this ancient problem: whether to chase the platoon advantage or ignore it.

Cleveland entered 2016 with a huge hole to fill; Michael Brantley, two years removed from a top-three MVP finish and probably the team’s best position player, was limited by a shoulder injury to only 11 games and 43 plate appearances. To make matters worse, in February, fellow outfielder Abraham Almonte was suspended for 80 games, plus the playoffs, for PEDs. And in June, one of the players brought in to replace Almonte and Brantley, Marlon Byrd, got tagged with a 162-game ban for his second positive PED test.

Cleveland weathered the storm thanks to a stupendous season from rookie center fielder Tyler Naquin and a breakout year from third baseman José Ramírez, who more or less replaced Brantley offensively. It also turns out that Cleveland’s best position player is not Brantley, but shortstop Francisco Lindor.

But there’s more to it than just a couple of young players picking up the slack. Remember how the McGuffin in Moneyball was trying to build a new Jason Giambi out of spare parts? That’s exactly what Cleveland has done with Brantley.

On August 1, the Indians picked up outfielder Brandon Guyer from Tampa Bay for Nathan Lukes and Jhonleider Salinas, who has been a large part of the solution in left field. The Cubs selected Guyer in the fifth round out of Virginia in 2007, then flopped him into the eight-player deal that sent Matt Garza from Tampa Bay to the Chicago Cubs in 2011. Since then, Guyer’s yo-yoed back and forth between Triple-A and the big leagues; at age 30, he’s never qualified for a batting title or hit double-digit home runs. But he does two things extremely well.

The first is soak up pitched baseballs. Guyer wore it 24 times in 2015, tops in the American League, despite batting only 385 times. This year, he was hit by 31 pitches in only 345 plate appearances, a rate of one HBP every 11.13 plate appearances, the highest in history by anyone with 300 or more plate appearances. In other words, Guyer got hit more frequently than Miguel Cabrera walked this year.

The second thing he does is hit the everlasting soul out of left-handed pitchers. For his career, Guyer, a right-handed batter, has hit righties at a .236/.307/.337 clip, which is unplayable for a corner outfielder. But he’s hit .289/.391/.470 against lefties, which is pretty much what Brantley (.310/.379/.480) hit in 2015 overall. This year, Guyer’s been even better against lefties, hitting .336/.464/.557.

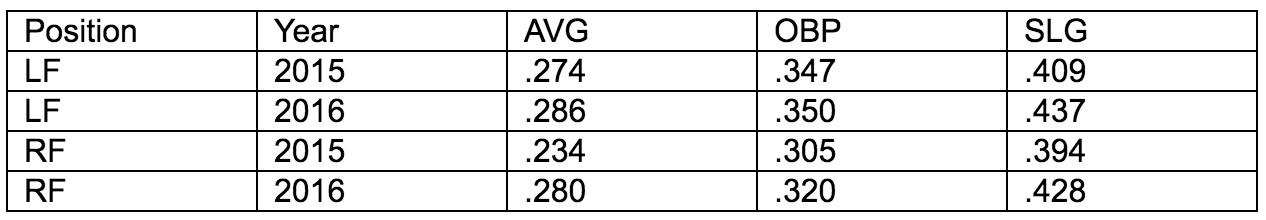

On August 31, Cleveland made another last-minute pickup, acquiring veteran Coco Crisp from Oakland, giving Cleveland four corner outfielders to work with: Guyer, who hits lefties but not righties; Crisp, a switch hitter with a .719 OPS against righties but a .625 OPS against lefties; Rajai Davis, a right-handed hitter with almost no platoon split; and the left-handed Lonnie Chisenhall, who’s posted a .784 OPS against righties and a .642 mark against lefties. Here’s how Indians corner outfielders have performed over the past two years, in 2015 with Brantley, and in 2016 with a rotating cast.

That’s in keeping with the Indians’ overall team-building approach, because Cleveland has pursued the platoon advantage with extreme vigor this year: The lineup is perfectly balanced with those platoons, three switch hitters (Lindor, Ramírez, and Carlos Santana), two lefties (Naquin and Jason Kipnis), right-handed first baseman Mike Napoli, and a catcher who doesn’t count for platoon purposes because no Indians backstop has hit worth a damn against lefties or righties this year.

The result: Seattle’s Robinson Canó made 275 left-on-left plate appearances this year; Cleveland, as a team, had 330.

One effect of this extreme platooning strategy, captured last month by FanGraphs’ August Fagerstrom, is that the Indians have gone absolutely berserk on off-speed stuff. This is substantially the result of Cleveland’s hitters hardly ever having to face breaking pitches that break away from them — the very source of the platoon advantage, which has to do with the movement on a breaking ball. For instance, a slider from an opposite-handed pitcher breaks in on the hitter and is easier to square up unless it breaks down and in out of the zone (a back-foot slider) or looks like it’s a ball but breaks over the outside corner for a called strike (a backdoor slider). For a same-handed batter, however, that slider looks like a strike but breaks away at the last second like Lucy pulling away the football.

Cleveland hitters haven’t had to deal with that very often this year. As a result, the Indians’ ramshackle lineup has a 106 sOPS+ against left-handed pitching and a 103 sOPS+ against right-handed pitching — not exactly the 1927 Yankees, but for a team with a bottom-10 payroll and serious injury issues, pretty good.

Swapping out outfielders and stacking the lineup with switch hitters is one way to get around the platoon advantage. It’s fitting for a small-market team with a long history of front-office innovation and a manager who’s revolutionized the modern bullpen this year by deploying Andrew Miller as a fireman. It’s the finesse option.

But what if a team isn’t big on finesse? What about a club that’s from a city of 2.6 million people, is owned by a media conglomerate fit for a Bond villain, and scored the second-highest percentage in baseball of its runs off homers? That doesn’t sound too subtle.

The good news is that baseball teams are like World War II movies: There’s more than one way to make a good one. Cleveland is like The Great Escape, in which the heroes rely on cleverness and meticulous planning. Toronto, by contrast, is like Stalingrad, the 2013 Russian blockbuster from Fedor Bondarchuk, a director who makes Michael Bay look like Wes Anderson.

(Watch this movie with subtitles even if you speak Russian, because the whole thing is one continuous series of explosions. It is a two-hour orgy of blue-and-orange color grading and heavy-handed symbolism whose climactic battle scene hinges on hitting a bank shot with a tank gun. It is noisy and vulgar in all the best ways.)

Which is to say that if you’ve got enough brute force, you don’t need finesse.

That’s how the Blue Jays have operated, because impressive though their lineup is, it’s almost completely right-handed. That could be a problem in this series, because so is Cleveland’s pitching staff.

The 12 Cleveland pitchers who faced the most batters this year are all righties, including likely ALCS starters Corey Kluber, Trevor Bauer, Josh Tomlin, and Mike Clevinger; and key relievers Cody Allen, Dan Otero, and Bryan Shaw. The Cleveland lefty who faced the most batters (103) this regular season is Miller, who is not only a reliever, but was for the first two-thirds of the season a Yankee. Even his presence is cold comfort, because righties hit only .153/.195/.279 against him this year.

The lineup Toronto used against Texas in Game 3 of the ALDS included seven right-handed hitters, left-handed-hitting DH Michael Saunders (whom Melvin Upton pinch-hit for against lefty Jake Diekman), and left fielder Ezequiel Carrera, a left-handed hitter with a reverse split for his career.

We often think of platoon-vulnerable sluggers as being like Ryan Howard, perpetually flailing at a slider in the dirt. But because there are more right-handed than left-handed pitchers in baseball, you won’t get far as a right-handed hitter if you can’t hit same-handed pitching. There’s a reason Guyer’s never held down a starting job, after all.

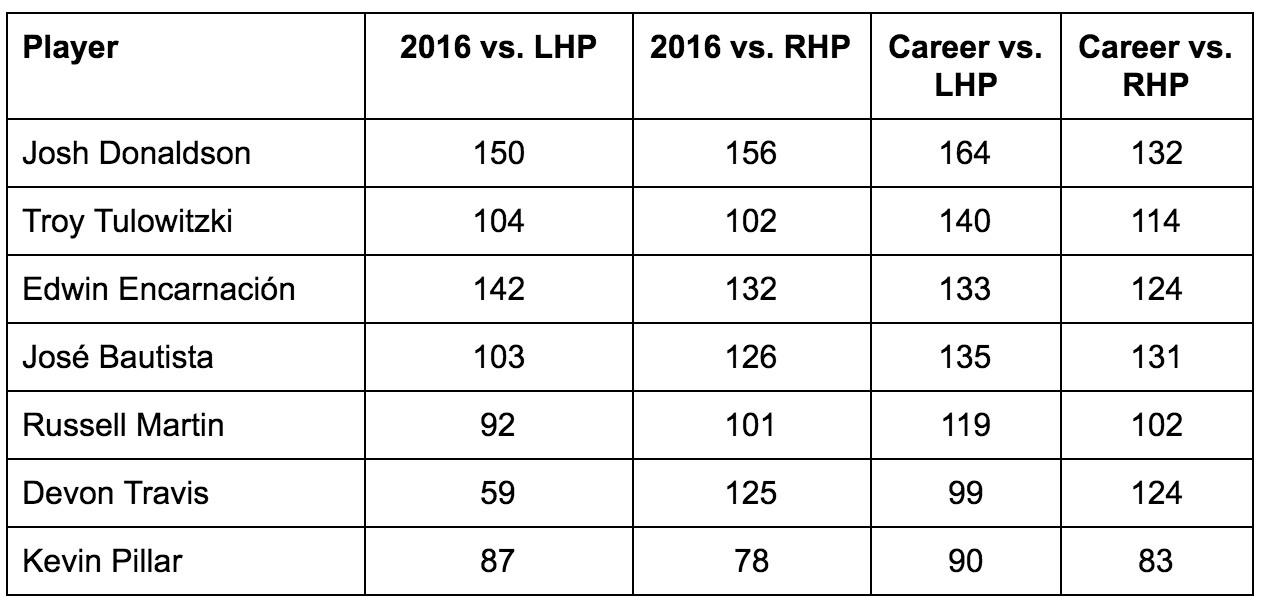

And because the Blue Jays have invested so heavily in established hitters — most notably Josh Donaldson, Troy Tulowitzki, and Russell Martin — they’ve managed to put together a lineup that’s heavily unbalanced on paper, but doesn’t have much trouble with same-handed pitching in practice. Here are the platoon splits (by wRC+) for Toronto’s seven projected right-handed starting position players.

Donaldson, José Bautista, and Devon Travis, in fact, have reverse platoon splits this year. (Though Donaldson’s and Bautista’s look like one-year flukes that are nonetheless mitigated by Saunders’s 147/108 reverse split this year, which itself looks like a fluke for two reasons: (1) Saunders’s career split is 90 wRC+ against lefties, 100 wRC+ against righties; and (2) if Blue Jays manager John Gibbons actually believed Saunders was better against same-handed pitching, he wouldn’t keep pinch-hitting for his DH with Melvin Goddamn Upton whenever a left-hander came up.) But if you look at the Blue Jays’ career numbers, you’ll find a pretty consistent pattern: Their big right-handed bats have a normal platoon split, but are so good as a baseline that they’re better against righties than most left-handed hitters are anyway.

That’s the alternative to Terry Francona’s ultraflexible lineup: If you can’t get around the wall, knock it over.

Cleveland and Toronto enter the ALCS with divergent styles, but similar results. They have the top two defenses in the AL by defensive efficiency, though Cleveland’s better on ground balls (thanks, Lindor) and Toronto’s better on fly balls (thanks, Kevin Pillar). Toronto has a deeper rotation due to Cleveland’s injuries, but Cleveland’s probably got the deeper bullpen. Miller’s the best reliever in the series and Francona’s commitment to a fireman role means Cleveland will get more out of Miller and Allen than Toronto will get out of Roberto Osuna and Joe Biagini. But Cleveland had a 122 ERA+ this year, compared to Toronto’s 113, an advantage that shrinks markedly when you consider that the Blue Jays are almost completely healthy while Indians starters Carlos Carrasco and Danny Salazar are out.

Surely the difference would lie with the offense, but Toronto had a .758 OPS against righties this year, .747 against lefties. Cleveland had a .763 OPS against righties, .748 against lefties.

Turns out there’s more than one path around the bases after all.