To understand why Wally West is Myles Garrett’s favorite superhero, you must go into the past. At first, Wally was just "Kid Flash," the sidekick to Barry Allen’s leading man. And Allen was a legend. For 30 years, his Flash averted hundreds of catastrophes, saved thousands of lives, and served as one of DC Comics’ most beloved heroes. Allen died in the iconic crossover story line Crisis on Infinite Earths, sacrificing his body to spare the rest of the world. Wally shed the "Kid" from his name and became the Flash. He had to follow that.

"He’s a funny guy," Garrett says of Wally. "He cares about a lot of people, but he’s underneath the shadow of greatness. We’re kind of in the same situation."

Anyone who’s watched the Texas A&M junior wreck quarterbacks on his way to becoming the nation’s best defensive end and the potential no. 1 pick in the upcoming NFL draft knows that the Arlington, Texas, native has come to define greatness at the college level, not be overshadowed by it. But it wasn’t always that way. Garrett, the youngest of three siblings, comes from a family of athletic excellence: His mom was a Hampton University All-American hurdler, his dad played basketball competitively, his brother played center for three NBA teams, and his sister won the 2014 weight throw NCAA championship for Texas A&M.

He looked at those closest to him and decided that he wanted to be great too. Garrett never imagined he’d find that greatness in football, a sport he once quit so that he could focus on basketball instead. That’s changed. Last season, matched up against Ole Miss’s Laremy Tunsil, the nation’s top offensive tackle, Garrett registered two tackles for loss, forced a fumble, and intercepted a pass. Yet Garrett identifies that game as the most frustrating of his career, because he felt he got no respect.

"Plus, I had a hold that should’ve been a sack," Garrett said. "What else could I have done? My dad’s like, ‘Don’t let it get to you. Next time, don’t let it be an argument.’ Fair enough."

Next time comes this Saturday, when Garrett, who’s been nursing an ankle injury, will get a chance for redemption as his undefeated, sixth-ranked Aggies take on undefeated, top-ranked Alabama and this year’s best tackle, Cam Robinson. Garrett might feel slighted, but the 2015 All-American and SEC sack leader’s play has led NFL executives to compare him to All-Pros.

Long before anyone saw that potential, though, Garrett had simpler goals.

"I wanted to be able to hang," the 20-year-old says, referring to his family. "I want to be able to look at them eye-to-eye and say I played at the highest level, too, and I did my thing."

Bob Wager was 3 years old when his father died, so he grew up looking for the male role model everyone else seemed to have. He lived in Johnstown, New York, an upstate town named by a father for a son, and when he got to high school, he met the football coach.

"My guy’s name is Barry Clawson," Wager says. "Was and is to this day my hero. One of those guys who just made you feel better by being around."

Wager, a running back, scrapped his way to Division III Springfield College, but his playing career ended when he fractured a vertebra. The school kept him on as a coach. In early 1992, he read Friday Night Lights, and that summer, Wager, then 22, sold his rusted-out Jeep, threw one suit and $500 in a duffel, and rode south on his new Suzuki Katana 600 motorcycle. He wanted to become the man he’d once looked for.

Eighteen autumns later, Wager stood in front of his newest freshman class at James Martin (Texas) High School. He’d worked his way up to the highest level of Texas high school football by, he said, helping boys become men. But that day, assistant coach Ronnie Jones pointed out a boy who already looked like a man, big and tall, just arms and legs at the moment, but clearly with the frame to be special.

"They don’t walk into your school like that normally," Jones says of Garrett. "You thought ‘gangly’ almost, on first appearance, like a fawn that wasn’t quite a deer."

Still Kid Flash, Myles didn’t yet see in himself what others saw when they watched him play football. He chose basketball because of Sean Williams, his brother. Garrett had hated football when he first tried it, as a 7-year-old; at least, he’d hated the black tape on his helmet that meant he was too heavy to touch the ball. "He came here big," his mother, Audrey, says. "Eleven pounds [at birth], and he had muscles when he was a baby. He might’ve had a fat belly or an ass, but … it’s like, ‘Dude. You muscular.’"

He wanted to play running back, because he didn’t mind being tackled. The self-described pacifist never wanted to kill bugs, and when he got on the football field, he realized he didn’t want to hit other kids, either. So he quit.

But by junior high, all his friends were playing, so Garrett figured why not, and joined football again if only to hang out with them and stay in shape for basketball, which he played through high school. When they made it to Martin, they experienced Wager’s intense weight-training culture, where calling a player a "freak show" was the highest honor a coach could give. The team even lifted before games. At the timed, end-of-practice 500-meter dash, it was common to puke.

"That’s how you know you’ve entered a different realm," Wager says of vomiting.

Though Garrett’s skills were still raw, by the middle of his sophomore year, Wager called Audrey, Myles, and his father, Lawrence, into his office one day after practice for a talk he’d had a few times before with other Division I–bound prospects, like Louisville’s Devonte Fields and TCU’s Kyle Hicks.

"He told me that if I could love football the same way I love basketball, even close, that I could be something special," Garrett says. "I wasn’t really worried about my production as a football player at the time. Just used it as a fun hobby. [The meeting] was kind of funny. ‘You see that [potential]?’ I don’t see that. But if you believe in me that much, I should prove you right. My mind-set changed immediately."

Garrett hadn’t consumed football as a viewer until this moment, and he wanted to see what others saw in the greats at his position, so he YouTubed highlights of past pass rushers. Though he still didn’t like to hit, he’d been put at defensive end because of his size, and had grown accustomed to the physicality. He discovered the names Bruce Smith, Reggie White, Lawrence Taylor, and the inventor of the term "sack," Deacon Jones. He watched any game film he could find and began jumping rope every day, though initially he "couldn’t even get over," says Anthony Gonzales, a Martin assistant coach who worked with Garrett and his fellow defensive linemen. But Garrett pushed harder in drills and began to fill out. He always performed best when challenged, so one year Gonzales told him he couldn’t get 15 sacks in one season. Garrett says he registered 21. He still wears the jersey no. 15.

About a month after meeting with Wager, the week the 2011 playoffs started, Garrett put 315 pounds on the bar to power clean. It was "Heavy Wednesday," as the team called it. He killed the first one, same with the second. Sweat puddled on the mat. As he picked up the bar for the final time, he slipped. The weights dropped directly on his right foot.

He wore a boot on the sideline and steamed silently as the playoffs progressed. That should be me out there leading. When Martin lost in the state quarterfinals, he couldn’t help feeling they’d have made it further with him. The Wager meeting is "a nice story," Audrey says, but Myles didn’t start putting football first until that postseason run, when he couldn’t play the sport he had come to love.

"It doesn’t happen often," Audrey says, "but when he’s pissed off, I don’t want to be in the room with him."

Garrett has always been a quiet kid. Growing up, he spent a lot of time at home in his room, reading or playing with toys. When Garrett committed to Texas A&M as a high school senior — he thought A&M had the best program and his sister, Brea, competed in track and field there — he held a sledge hammer limply at his side and tilted the microphone away from his mouth.

He got that quiet nature from Lawrence, and from his grandmother, whom everyone called Gran. She was the only person in his immediate family without an athletic background. He says his first memory is of opening a present from her, a Nintendo 64 with Banjo-Kazooie, and asking if they could go to her house to play. Myles never went to day care, only to Gran’s, where they’d also play Monopoly and watch Law & Order, and where she made Myles "perfect" oatmeal. She was small and pleasant, and she encouraged her grandson to be different and caring. She taught him hard life lessons.

His parents also gave their kids books, sometimes challenging ones. After his brother Sean gave the 4-year-old Garrett his first reading lesson by sounding out the names of characters in Mortal Kombat, Garrett’s shelf started to fill with The Cat in the Hat, then Goosebumps, the Left Behind series, and his mom’s copies of Dean Koontz novels.

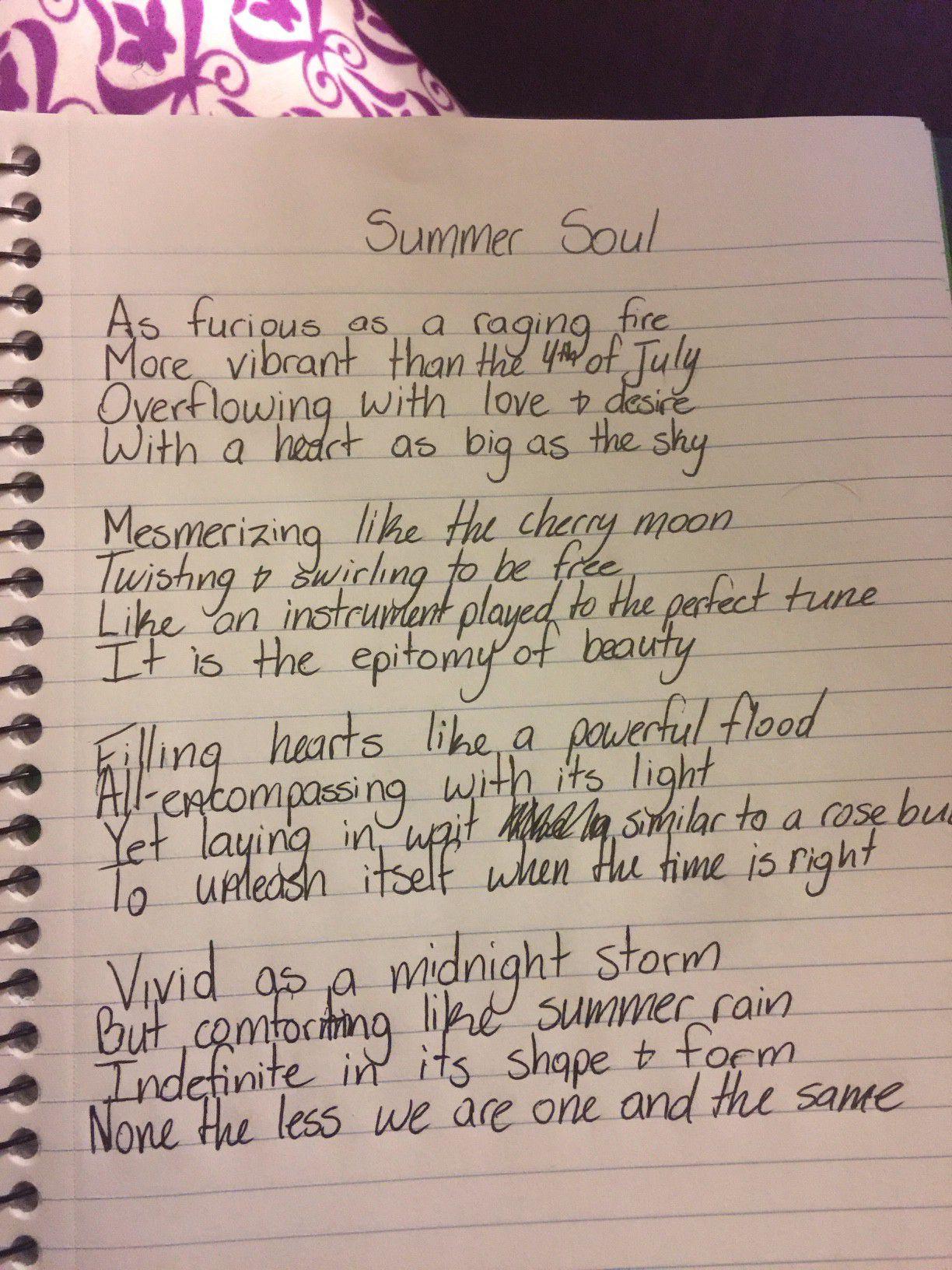

Prose led to poetry, and the first poet Garrett came to love was Muhammad Ali. Garrett started writing his own poems and found comfort in the act regardless of what was happening in his life. Throughout high school, when asked to present his work, he preferred teachers or classmates to read his poetry aloud in front of the class.

Lawrence shared the same reserved nature. He tried to impress on his son that it didn’t matter what anyone else did; he could control only himself. But Dad, Myles would say, referees don’t listen to me when I tell them about holding. Then don’t complain. Linemen poked my eyes. Buy a shield mask. Other kids played dirty or celebrated too much. They put on shorts and socks just like you do.

"They’re mirror images of each other," excluding football, Audrey says. "[Myles’s] aggression on the football actually tripped us out."

That aggression on the field was matched by a gentleness off it. He’s Lawrence off the field ("cool, even-keeled") and Audrey on it ("I’m a microwave, I go from zero to hot").

Gonzales remembers a day when he misplaced Myles when taking his position group back to a district middle school for a reading program. He looked down the hallway. Nothing. Bathroom. Nothing. Classrooms. Nothing. He "freaked out," he says.

"How do you lose a 6-foot-3 giant in a middle school?"

Then Gonzales remembered the library, where the librarian had sorted players into groups to go read with the younger kids. When Gonzales pulled open the door, he spotted Garrett sitting at a table in the corner, surrounded by four special needs students giggling at the impossibly large boy thumbing through picture books with them.

"I think there’s a misconception that [Garrett’s personality] has been an act," Gonzales says, "that he’s trying to portray something. He’s not. This is the way he’s always been."

Ask any teacher at Martin and you’ll get a similar story about the soft-spoken kid who barely fit into his desk but had the manners to at least feign interest in their subjects. Mostly he read and talked about dinosaurs, surprising more than one teacher by not growing out of the Jurassic age.

He still hasn’t. He tried to dig them up in his backyard as a kid, nearly attended Ohio State because of them, assigned homework about them, ranked them, received them, and has even been compared to them. He says he would rather be a paleontologist than a Super Bowl MVP. People pepper him with random dino facts and expect him to know them. He says he doesn’t really tire of it.

As Garrett’s fame grew toward the end of high school, a few teachers tried to prepare him for life after graduation. English teacher Bennett Mitchell gave him Rudyard Kipling’s poem "If — ." Environmental systems teacher Jennifer Spraggins kept him humble by good-naturedly teasing him, Well, five-star, I see you schmoozing in the halls every day, but never this incredible 40-yard speed we always hear about. Statistics teacher Derek Moore handed him a Snickers bar.

Moore had noticed the antics of another Aggie, Johnny Manziel, and didn’t want his student, a trusting kid, going in blind to college’s temptations. When Garrett finished the Snickers and smiled, Moore said, "You’re ineligible." When Garrett looked confused, Moore warned him to be wary of anyone who offered him anything in College Station.

Sometimes, when he felt bored during senior year, Garrett would duck into Room 192, Vikki Chilton’s physics class. She never taught him, but he goofed around with friends in there and had enjoyed his own physics class, so he helped students with questions. Chilton started joking with Garrett when he wore A&M gear, asking when he would flip his commitment to Arkansas, where her two boys went to school. Garrett responded by flashing the grin that many of Martin’s teachers still remember him for.

Chilton’s class conducts an experiment every year that requires students to calculate the height of something by dropping an object from that height and measuring its fall. To help her students understand, Chilton compares the heights to someone they all know, the now-6-foot-5 Garrett. Now, as Chilton walks around her room and hears her students chatter during the experiment, she’s noticed that, with each passing year, Myles Garrett gets a little bit taller.

One of the lessons his brother Sean had taught Garrett was how easily a person could be derailed. At Boston College and in the NBA, Sean was suspended and arrested multiple times for altercations and marijuana possession. A shot blocker and first-round draft pick, Williams bounced around the D-League and played only one full season in the NBA because, his family says, he smoked too much weed and didn’t listen to anyone trying to help.

Garrett was determined not to repeat those mistakes. The summer before his junior year, after he attended his first and only football camp at the University of Texas, he shot up the recruit rankings. Wager’s intensity incubator coaxed Garrett to regularly give what coaches called "fanatical effort." He burned up the jump rope for 10, 15, 20 minutes at a time, fluidly managed hurdles, squatted 400 pounds, recorded 8.5 sacks in one game his senior year, and lost science worksheets in his locker among the recruiting letters. Texas A&M coach Kevin Sumlin visited in his Swagcopter.

"He’s so laid-back, just smiled and didn’t say anything," Sumlin told ESPN about the visit. "I was like, ‘This is the guy we watched on video? This is that guy?’"

The illuminati of college football arrived to see Garrett sling weight. One afternoon, standing in the garage door bays in Martin’s weight room were Alabama’s Nick Saban, LSU’s Les Miles, Notre Dame’s Brian Kelly, and Texas’s Mack Brown, among a handful of others. Garrett pumped through his six-minute reps at each station, running a lap around the track after every two reps. That showcased his legs, which had gotten so strong that when someone hit him low, he’d keep his balance as he churned forward. The Martin coaches compared him to a slinky and assigned a nickname, "Gumby."

"Well, what do you think?" asked one of the recruiters when Garrett walked up after the workout. He meant: "How do you feel that I’m here to see you?" (None of Martin’s staff would describe the coach beyond saying that he still helms one of the nation’s top programs.)

"Huh," Garrett says. "I thought you’d be bigger."

Coaches and players guffawed. Classic Myles, they thought. No disrespect meant; he just treated the question like it came from one of his friends. Coaches and players wondered how that sort of innocence was possible, until they remembered that this was the same kid who, when a TV station asked where he wanted to play college ball, said, "The sec." Not the S-E-C. The "sec."

A few months later, on Christmas Day 2013, someone knocked at the door of the Wager house. Bob’s then-9-year-old son, Gage, and 7-year-old daughter, Mia, were confused. No one usually came by the house on Christmas. The kids didn’t know it yet, but the next day they were flying to Disney World with their mom and dad and the Garrett family for the Under Armour All-American Game. They rushed to the door. It swung open to reveal Myles Garrett. He held one Mickey Mouse T-shirt and one Minnie Mouse T-shirt.

In Florida, Garrett stacked up six tackles, four for a loss, and a sack. 247Sports.com felt the performance merited a change in its Class of 2014 recruiting rankings. Garrett became the nation’s no. 1 recruit, leapfrogging a running back out of New Orleans named Leonard Fournette.

One night a few weeks earlier, Gonzales had walked into Martin’s dark weight room. On the way to his office to lock up, he heard faint music. He had turned off the stereo system earlier. As his eyes adjusted to the lack of light, he made out a figure on his back doing dumbbell bench presses. Garrett removed his blasting ear buds and explained he wanted an extra set. Gonzales carried on locking up for a few minutes.

"All right, man, it’s time to go," he told Garrett, who asked for a few more minutes. Gonzales found something else to do, and that conversation happened two more times before Gonzales finally locked up for the night.

Upon arriving at A&M, the 18-year-old promptly broke Jadeveon Clowney’s SEC freshman sack record in only nine games. In his two-plus total years in College Station, opponents have respected him, coaches have feared him, and NFL fan bases have discussed trading the pick pile for him. Last season, he led "the sec" in sacks.

During his record-breaking freshman season, Gran died from Alzheimer’s and dementia complications. Audrey and Garrett both say it was the most difficult thing he’s faced. The family, Garrett says, lost its "anchor." He coped by playing pickup basketball and writing poetry.

"He put on a brave face for everybody," Audrey says. "And nobody ever knew. He struggled his freshman year. He still struggles with it."

It was the first family death Myles had experienced. He took it as a reminder to appreciate everything as it happens. A lot of things have changed since then, but Myles is still similar in many ways: He says he has never smoked, has never drank, doesn’t use social media, always prays, and recites Muhammad Ali’s "Truth" before taking the field. He’s also not the same, because he couldn’t be.

As Myles has continued to torpedo offenses, Audrey and Lawrence have developed a system to handle the people who want to get close to their son. They’ve cocooned him, worried about the son who was always eager to please friends and family, who said yes to seemingly everything. As Audrey handled media and fans while Lawrence took care of inquiring agents or marketers, they let Myles be himself, watching anime (Dragon Ball Z, InuYasha) and cartoons (Tom and Jerry, Jonny Quest), reading books (The Sixth Extinction), and studying Japanese and Spanish for the humanitarian trips abroad he’s planned after NFL retirement.

Until then, his apartment remains the crossroads. He lives alone, preparing. He likes forgetting about football sometimes, just for a little, with the aid of a carefully chosen collection of items on his walls that remind him of the bigger picture.

"I love the game and I love winning and competing," Garrett says, "but they help me remember there are things much greater than football. To remind me this is just games, just entertainment for people."

Around the apartment hang several Bible verses (including John 3:16), three letters from Wager’s 81-year-old mother, two photos of Ali, one group shot of DC heroes, and a poem that a Garrett family friend recited before stepping into the ring for a boxing match of his own. The hangings remind Garrett of life’s relative smallness, which he likes, because the boy who says he hates the spotlight knows it’s about to get much brighter.

The last reminder on the wall is a sheet of paper bearing Kipling’s "If — ," the poem gifted to Garrett by his high school English teacher. It’s about staying true to yourself through highs and lows. He particularly likes the last stanza:

If you can talk with crowds and keep your virtue,

Or walk with Kings — nor lose the common touch,

If neither foes nor loving friends can hurt you,

If all men count with you, but none too much;

If you can fill the unforgiving minute

With sixty seconds’ worth of distance run,

Yours is the Earth and everything that’s in it,

And — which is more — you’ll be a Man, my son!