Simmons vs. Gladwell: The Future of Football

Sagging ratings, national controversy, horrifying head injuries, shameless greed: The conversation about the NFL has officially changed. Is it too late to fix it?

By Bill Simmons and Malcolm Gladwell

Simmons: "Is he crying?"

"He’s just having trouble breathing. He’s disoriented."

"It looks like he’s crying."

"Maybe it’s both."

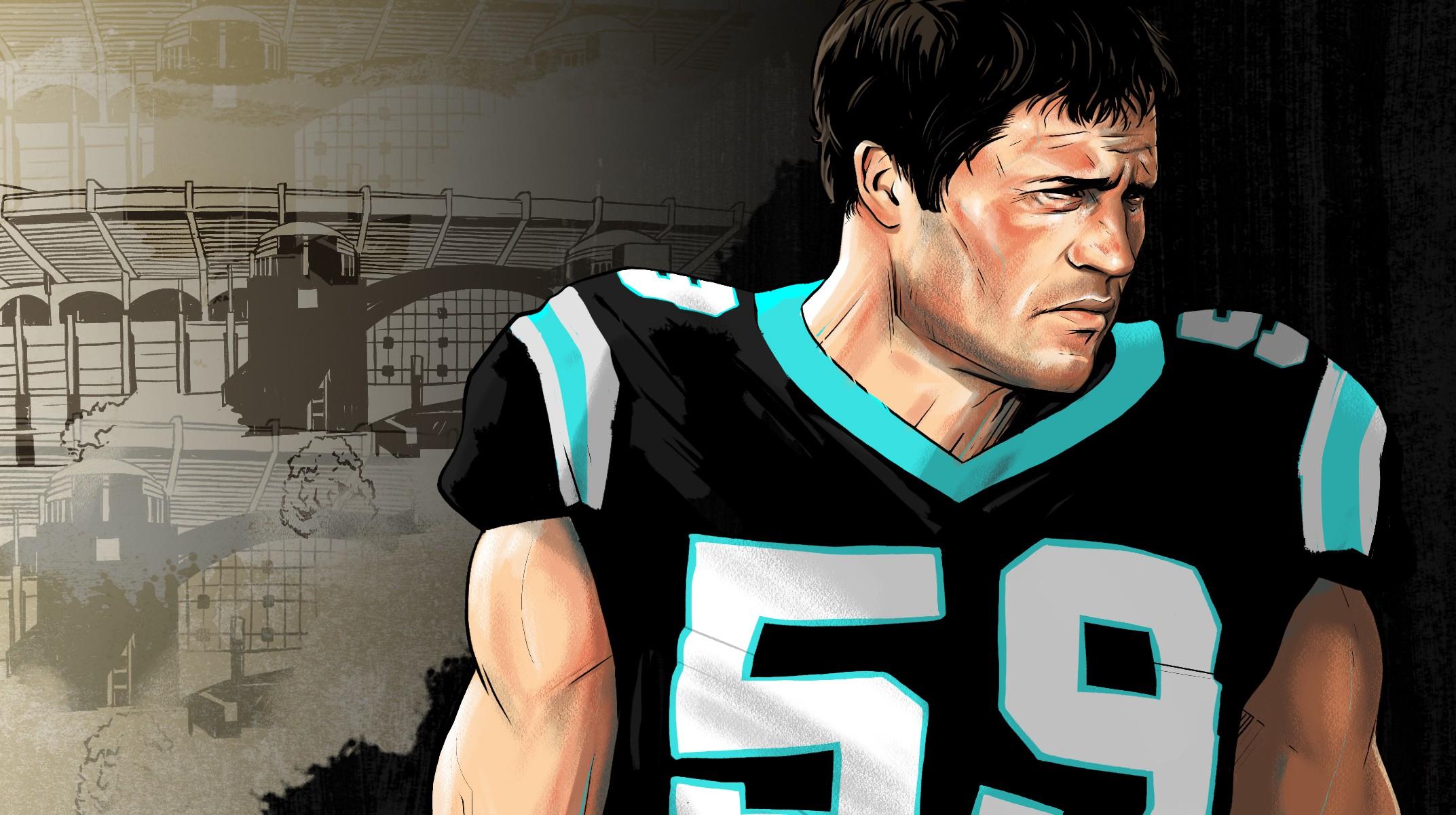

My son and I were discussing the Carolina Panthers’ Luke Kuechly, who had just spent three hours terrorizing the New Orleans Saints during a typically disjointed Thursday-night game. Everyone loves Kuechly because he doesn’t just play middle linebacker. Kuechly zips around as if he’s manipulated by a Madden controller, only the person controlling him knows every play in advance. He covers acres, not yards. Earlier in the second half, Kuechly had swallowed up a delayed screen after dismissively shoving an enormous lead blocker out of his way, no different from someone pushing aside a staggering drunk in a nightclub. That sent NBC’s Cris Collinsworth into a chortling frenzy. Middle linebackers do that stuff in high school, but not here, not in a league littered with 300-pound linemen. It’s just not supposed to happen.

After you watch Kuechly for enough plays, you start thinking he’s superhuman in a LeBron/Lesnar/Affleck-as-Batman kind of way. But that’s the thing — in a collision sport littered with gargantuan linemen and muscle-bound sprinters, nobody is. Maybe an hour earlier, Mark Ingram had gotten smoked by a tackler and fell onto his back, only his arms jolted straight up as if he were re-creating Elijah Wood’s electrocution scene in The Ice Storm. (And yes, NBC couldn’t have cut more quickly to commercial.) In the Carolina game, Kuechly tackled Tim Hightower high right as the 226-pound running back was lowering his head, leading to the three scariest words in football that aren’t "Here’s Tony Siragusa" … that’s right, helmet to helmet.

Kuechly was sent sprawling before rolling over onto his stomach, writhing around with his appendages flapping. Players huddled around him. Voices hushed. Commercials happened. Kuechly eventually landed on the injury cart, looking decidedly less than superhuman. Was he really crying? Was something else going on?

I hopped on my iPad, Googled "Kuechly concussions" and learned that he had suffered one last season that sidelined him for weeks. This was his second. God knows how many undiagnosed ones he’s had. The following day, former Patriot Christian Fauria tweeted that Kuechly hadn’t been crying; Fauria claimed that sometimes a concussion disorients you so much that you freak out. Former Seahawk Chad Brown interpreted it differently, tweeting that concussions affected the part of the brain that controls emotions and would make him sob for hours … but that it was worse "when rage is the emotion." Whatever happened, Luke Kuechly went from "heat-seeking missile" to "hyperventilating, blubbering mess" in one play. The following morning, he appeared in this photo on Instagram:

… and that was supposed to make us feel better. Or something.

Forty years from now, we won’t remember a specific concussion that transformed the way we watched football. I remember joking about Troy Aikman’s Concussion Face in columns as recently as the early 2000s (and only because I didn’t know any better). I remember my feelings slowly shifting after that unforgettably violent Steelers-Ravens playoff game in 2009, a night plagued by multiple knockouts and a 30-second span when we thought Willis McGahee was dead. Not hurt — DEAD. I remember Jamaal Charles getting rocked in the 2013 Colts-Chiefs wild-card game, then being examined on the sideline and realizing, "Holy shit, it’s the playoffs and he’s still not coming back." I remember Julian Edelman getting belted late in Super Bowl XLIX, right after his season-saving third-down catch over the middle, and talking myself into Edelman NOT being concussed … but only because of the stakes.

These dicey moments have changed how we watch football, that’s for sure. Twenty years ago, I would have written a joke about the Luke Kuechly Concussion Face and moved on to the next riff. Now I’m a little haunted by it. We have too much information about head injuries. I feel like an accomplice. Everyone wondered why the NFL’s ratings slipped for those first nine weeks, but Malcolm, maybe it starts there?

Gladwell: I couldn’t agree more, Bill. Football has a problem. I thought of this the other day when I had the fun job of interviewing Astros GM Jeff Luhnow at a RAND conference in Santa Monica. He talked entirely about analytics, and what all the data they now collect mean for the decisions they make — how they didn’t bid on a major free agent after doing a micro-analysis of his swing, or what can be learned, in real time, by precisely measuring the rotation on a pitcher’s slider. That kind of stuff. The audience found him fascinating. Here’s the thing, though: I’m guessing that less than half of the people in the room were actually baseball fans. But it didn’t matter: There is now a second conversation about baseball — the Moneyball conversation — that is interesting even to people who don’t follow the first conversation, the one that takes place on the field. Same thing for basketball. There’s an obsessive first conversation about a beautiful game, and a great second conversation about how basketball has become a mixed-up culture of personality and celebrity. Boxing had a wonderful second conversation in its glory years: It was a metaphor of social mobility. Jack Dempsey, one of the most popular boxers of all time, dropped out of school before he even got to high school; Joe Louis’s family got chased out of Alabama by the Ku Klux Klan. That underlying narrative made what happened in the ring matter. When the second conversation about boxing became about people like Don King and the financial and physical exploitation of athletes, the sport became a circus.

So what’s the second conversation about football? It’s concussions. There’s the game on the field and then there’s a conversation off the field about why nobody wants their kids to play the game on the field. How does a sport survive in the long run when the second conversation contradicts the first? I thought you were going to mention the other excruciating Panthers game this season: the league-opening-night Super Bowl rematch with the Broncos, where one Denver defender after another made a run at Cam Newton’s head. After that happened a second time, a few weeks later, remember what Newton said? He doesn’t "feel safe on the field" anymore. Newton is one of the league’s biggest young stars, and the most memorable thing he has said all year is that playing football now scares him. Good lord.

Simmons: I like your "second conversation" theory. For college football: Should they pay the players? For college basketball: How do we stop one-and-done? For golf: Will Tiger ever get his mojo back? For tennis and men’s soccer: Why is America getting its ass kicked? For women’s soccer: How can we convince Americans to care beyond the World Cup and the Olympics? For UFC: Can it thrive long term with so much superstar turnover? For hockey: How can we kidnap Gary Bettman until 2032 without anyone getting arrested?

Gladwell: Bettman’s never leaving. He’s going to have himself cryogenically frozen at center ice in Madison Square Garden.

Simmons: I’d rather have Frozen Bettman as the NHL commissioner. At least they’d finally stop expanding. (We reached Peak Bettman with the Vegas Golden Knights, which sounds less like an NHL expansion team and more like a brothel.) Anyway, I believe the NFL is juggling more "second conversations" right now than any league in the history of professional sports. In no particular order …

1. Concussions

2. An undeniable change in the way the game is being played

3. An undeniable decline in the quality of play in September and October

4. The commissioner’s serial abuse of his power

5. Conflicting policies regarding painkillers, HGH, steroids, and marijuana

6. A looming free fall in youth football participation numbers

7. A lack of under-30 superstars who resonate with fans

8. National anthem protests (and whether it affects certain fan bases)

9. Billionaire owners repeatedly extorting their fans to pay for new stadiums

10. Millennials and cord-cutters gravitating more to the NBA and soccer

11. An oversaturation of TV games because of shameless greed

12. That pre-election decline in ratings, and whether it should be considered an aberration or something more

That’s TWELVE second conversations that have nothing to do with things like "Who’s winning the Super Bowl?," "Who are you gambling on this week?" and "Should announcers mention multiple times during Chiefs games that Tyreek Hill punched his pregnant girlfriend in the stomach and tried to strangle her back when they were in college, or is once a game good?"

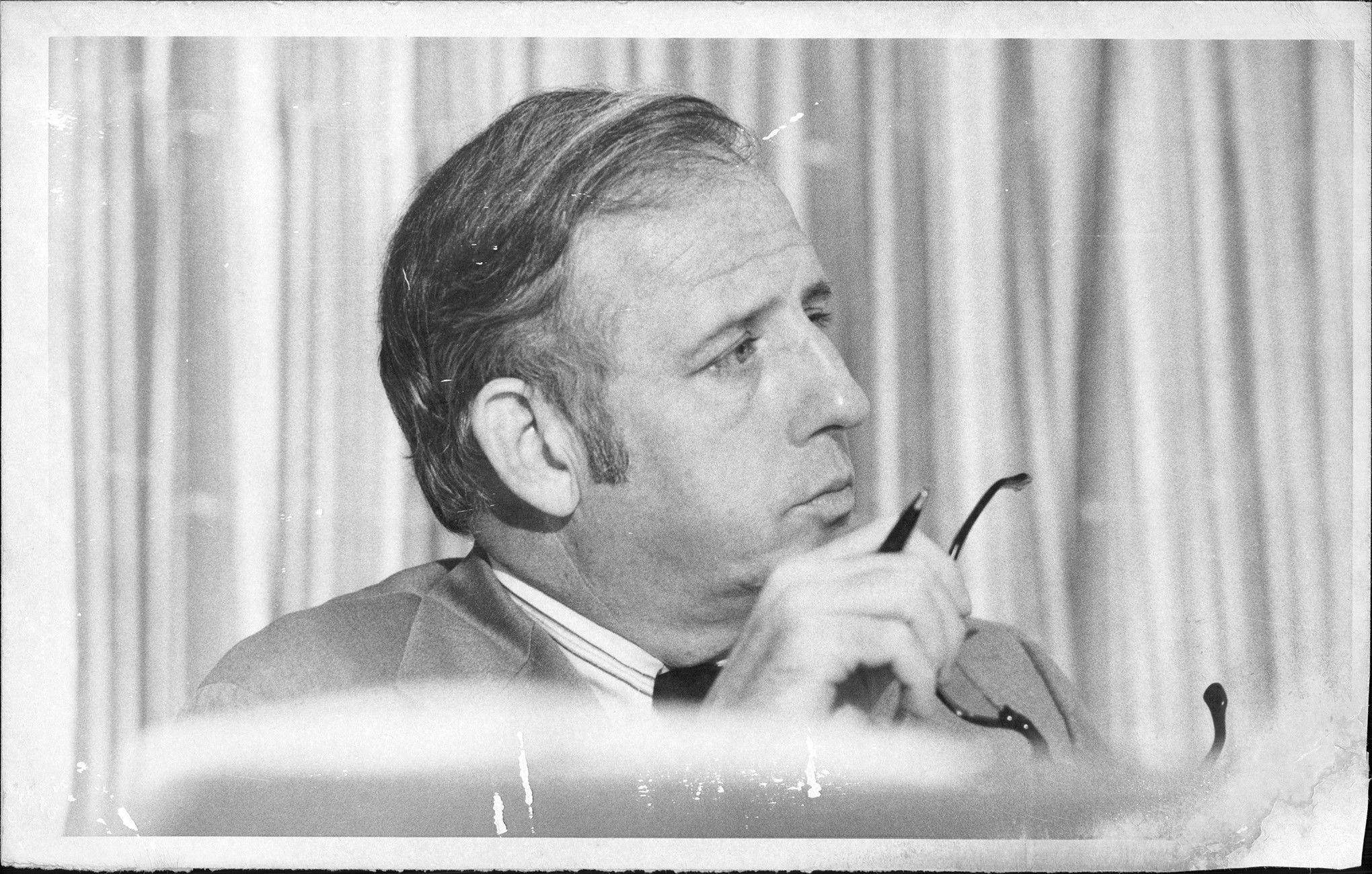

Gladwell: A quick digression about no. 4: Roger Goodell. Goodell’s dad, Charles, was a five-term congressman from upstate New York, and one of the earliest and most courageous voices in Washington against the Vietnam War. He was then appointed to the Senate, to fill the vacancy left by the assassination of Robert Kennedy. In his first campaign after his Senate term was up, he ran what has to be one of the all-time great TV ads:

Goodell lost, by the way, because he would not abandon his principles. He had balls, which makes me think that Roger might not entirely be a lost cause. Maybe there’s a heavyweight lurking somewhere in his DNA. For the moment, though, I think he’s too busy going through old physics textbooks with a Sharpie, crossing out mentions of the ideal gas law.

Simmons: Just so you know, "His dad had balls, which makes me think the son might not entirely be a lost cause" is what Knicks fans and Lakers fans mutter to themselves before falling asleep every night. But Goodell isn’t the issue anymore. He’s already been exposed as something of a bulletproof vest for 32 billionaires and almost-billionaires, their pet Rottweiler who does whatever it takes to protect their bottom line. Goodell doesn’t work for current players; he’s not overpaid to care about their long-term welfare, only to pretend that he cares about it. And he certainly doesn’t care about the retired players, as we found out here and here and especially here. For those and so many other reasons, we started seeing through Goodell’s draft-day bear hugs a long time ago. The next guy will behave just as callously. That’s the job description.

Back to those 12 secondary conversations — how have they affected the NFL’s erratic ratings in 2016? In the first three post-election weekends, the NFL’s signature games drew more attention than ever, in particular, Steelers-Cowboys (stupendously entertaining), Patriots-Seahawks (still hurts) and Cowboys-Deadskins (an impossible 35 million viewers on Thanksgiving!). Any NFL owner could easily argue, "That nonstop coverage of the most polarizing election of our lifetimes hurt everyone’s ratings, not just ours, so everything’s fine!" But Americans in 2016 are less likely to watch shitty football, and the NFL’s week-to-week ratings reflect that, too. Airing "national games" three out of every seven nights hasn’t helped, nor have those three London weeks when we’re overwhelmed with FOURTEEN straight hours of professional football. (Wasn’t this how ABC and NBC eventually murdered Who Wants to Be a Millionaire and Deal or No Deal, by the way?) Do the 32 owners realize that they advertently diluted their product? Apparently, yes! Mike Florio reported on Saturday that the NFL might cancel Thursday-night football, an astounding concession from the greediest league in professional sports history. The National Football League WALKING AWAY from piles of money??? And you thought you’d seen everything, Gladwell.

Gladwell: I was surprised to hear Cris Collinsworth say, on your podcast, that when he has to announce a Thursday game followed by a Sunday game, he can no longer keep the names of the players straight. When the smartest football analyst in the game gets overloaded, that ought to be a sign.

Simmons: So let’s say the NFL dumped Thursdays and beefed up Sunday and Monday nights, which would undoubtedly improve the week-to-week product and make signature games seem more special. But once ratings start dropping for signature games — and they will — I believe the concussion crisis will be remembered as the dominant reason. Once upon a time, we expected our NFL gladiators to annihilate each other. That’s one of the reasons we loved football. We never blanched at the repercussions unless Dennis Byrd got temporarily paralyzed or Bo Jackson’s hip splintered out of its socket — and even then, it’s not like we turned the channel. But as players kept getting bigger and faster, and collateral-damage injuries kept piling up, and concussion awareness started kicking in, and those devastating Mike Webster–type stories started trickling out … you could feel everything shifting, right?

Gladwell: In terms of how we watch football, high-definition television has clearly been a two-edged sword for the NFL, hasn’t it? It makes the drama of the game come alive, because we can now see the action in so much more detail. But it also means that when Luke Kuechly is writhing in pain on the ground, we can see every emotion on his face. That’s not a trivial matter. There’s a particular emotional expression that the psychologist Paul Ekman has labeled "Action Unit 1," which is when your inner eyebrows rise up suddenly, like a drawbridge. It’s almost impossible to do that deliberately. (Try it sometime.) But virtually all human beings do Action Unit 1 involuntarily in the presence of emotional distress. Watch babies cry: Their inner eyebrows shoot up like they are on hydraulics. And when you see that expression appear on someone else’s face, that’s what triggers your own empathy.

The point is, in an age when this kind of intimate information about other people’s emotions is available to us when we’re watching TV in our living rooms, a game as violent and painful as football becomes really hard to watch. The first time I realized this was after a hit on Wes Welker in a Broncos playoff game, in the season when he had multiple concussions (2013). I had just bought a new big-screen TV, with an incredible picture, and when the camera zoomed in on Welker, I was so shaken that I had to turn off the game. I wonder how many other people did the same thing. So, yes, we really watch football differently now.

Simmons: And it’s being played and governed differently. You can’t physically punish quarterbacks anymore, but quarterbacks also don’t want to be punished — so someone as fearless as Cam has to reprogram himself (on the fly!) to think about his own welfare before the team’s welfare. As this is happening, defenders are reprogramming their brains to punish offensive players safely, which is fucking impossible. And coaches are reprogramming their brains to call plays that don’t result in receivers and tight ends getting clocked over the middle — like what happened three Sundays ago, when Brady inexplicably led Gronk right into an Earl Thomas car crash and had Patriots fans Googling things like "Is perforated worse than punctured?" Even after everyone finishes updating their brains like an iPhone, I’m still not sure what will happen, because Safe Football makes about as much sense as Safe Boxing.

The other issue: 2011’s collective bargaining agreement chopped the total number of practices and eliminated two-a-days (making it harder for coaches to prepare players), but also created an unexpected salary-cap loophole that prioritizes cheaper labor (draft picks and undrafted free agents) over pricier veterans. Vince Wilfork was one of the most popular Patriots of the Belichick-Brady era, but he would have counted for $8.9 million against their 2015 cap. So they dumped him in March 2015 and spent a first-round pick on Malcom Brown, who signed a four-year deal worth less than one Wilfork season. Any shrewd franchise would handle it that way, right?

Unfortunately, when you chop practice time, lean on youngsters AND incentivize franchises to dump veterans, you sacrifice a dangerous amount of continuity (as Kevin Clark predicted for The Ringer in early September). You’re asking teams — basically, every franchise that doesn’t have Belichick, Carroll, Tomlin, Harbaugh or Reid as its coach — to figure out their rosters and schemes on the fly. And you lose the old guys saying stuff like, "There’s a way we do things here," and, "Young fella, lemme give you a little advice," and even, "Trust me, don’t send her that dick pic." My simple fix: Every franchise can designate two veterans who will have only half of their salaries count against a given year’s cap, as long as the veterans have spent nine straight years on that team. Why not promote a little loyalty and continuity?

(Thinking.)

Wait — this would really help the Patriots with Tom Brady’s cap figure! I LOVE THIS IDEA!

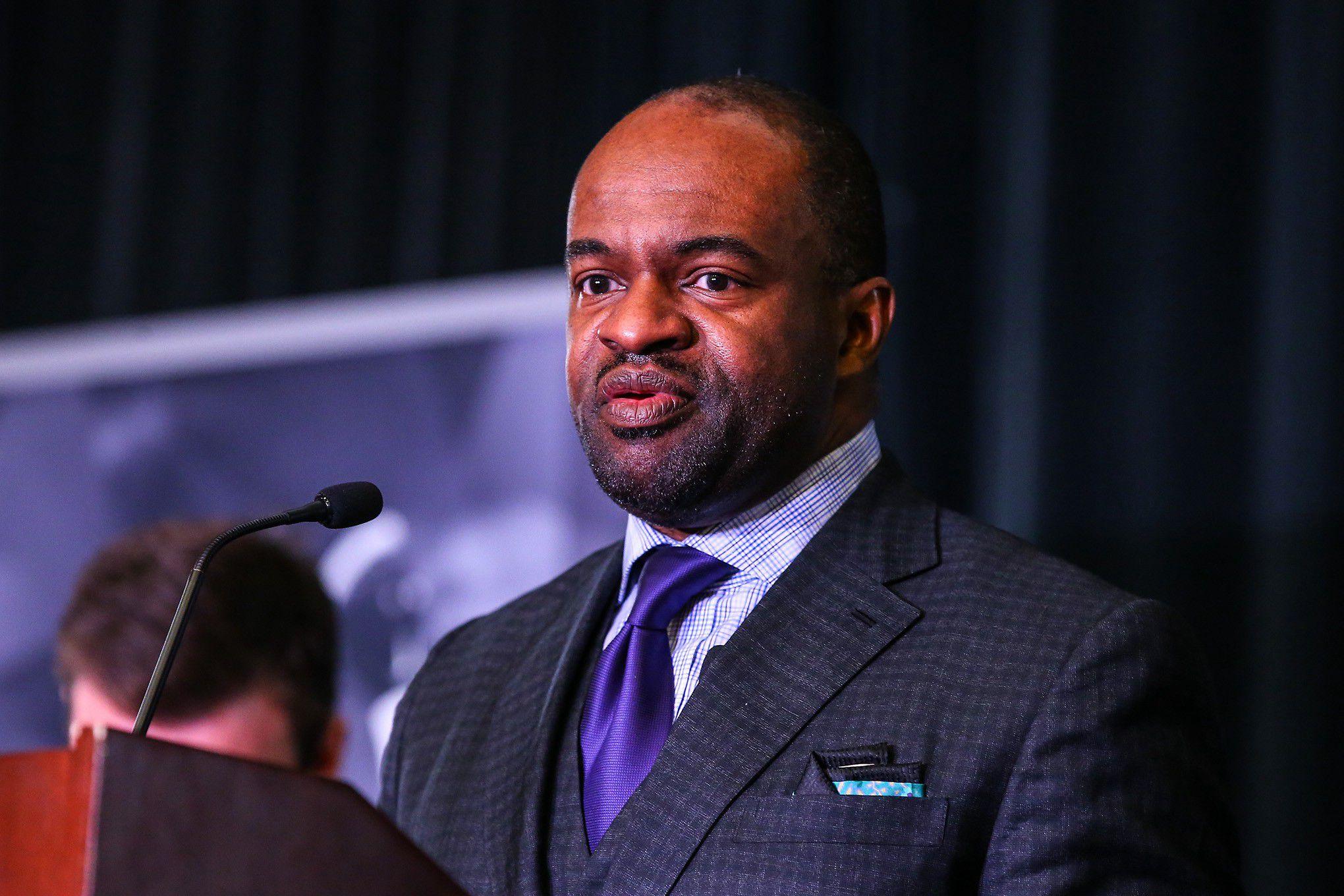

Gladwell: We talked about this with DeMaurice Smith, the head of the NFL Players Association, when the three of us had our conversation back in the summer on Any Given Wednesday.

Simmons: You don’t have to plug my show anymore — it’s gone.

Gladwell: It’s a plug for the reruns! Smith negotiated one of the all-time-worst collective bargaining AGREEMENTS in history in 2011, when he agreed to a smaller share of total revenue for the players and also to the salary-cap loophole that you’re talking about. But I have to say that his defense kind of convinced me: He has no bargaining power. The only card he can play is a strike, and the odds of getting the players to walk off the job are basically zero. And the owners know that. Think about it: The length of the average career fell by two and a half years from 2008 to 2014, and now stands at under three years. How do you convince the majority of players to risk a third of their projected careers in pursuit of a better deal? He’s right! It’s impossible! Do you remember what else he said? (I think this was off-camera, so forgive me, DeMaurice.) The owner that he feels is most open to improving the lot of the players and thinking rationally about the future of the league is … Dan Snyder. As you would say, Bill: Ladies and gentlemen, your 2016 National Football League! Living proof that in the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king. I say we turn this exchange into an open letter to Snyder, since he is apparently football’s last best hope for salvation. Are you listening, Dan? Here are our best suggestions for saving the National Football League.

Simmons: OK, we’re doing this! My first suggestion: Dump the preseason and adopt a 17-game schedule with two bye weeks, 50-man rosters and 12-man practice squads. So instead of taking 17 weeks to play 16 games, it’s taking 19 weeks to play 17 games. Yeah, we lose Hard Knocks, but we also avoid preseason injuries (and the irredeemable preseason games), gain everyone more rest and gift-wrap the networks another week of REAL football to sell. But here’s the big wrinkle … players could suit up for only a maximum 16 of the 17 games.

Gladwell: I LOVE this.

Simmons: Oh yeah! We’re going full Popovich! Imagine Pittsburgh announcing on a Monday, "We’re resting Big Ben against Cleveland this week," as the pathetic Browns try to take it personally before realizing that, yeah, it makes total sense and they can’t blame the Steelers. Most of these overmatched head coaches can barely figure out when to go for two; can you imagine them figuring out the ideal week to bench Von Miller or Odell Beckham Jr.? Imagine the ramifications on gambling, fantasy and the 24/7 sports-talk cycle. What about a contender blowing a first-round bye because its coach wanted to rest his best four starters for Week 18 and never realized Week 18 would mean something? What about Week 18 existing, and even better, us not feeling guilty about it? I love this idea.

Gladwell: I would actually go further: Players should be limited to 15 of 17 games. Football has lent itself to complication, and two "bye" games for every player just doubles the fun. Also, surely the goal here is to materially decrease the injury burden. Which leads me to my first issue: In mid-November, a group at Harvard University issued a 493-page report on health care in the NFL. Their main recommendation was that the physicians who take care of injured players should no longer report to the clubs. That’s a clear conflict of interest. They want health care decisions to be made by a neutral medical committee, on the principle that the person who decides if a player is healthy enough to perform really ought to represent the player. I should point out that this is maybe the most obvious point ever, and one that the rest of the world has taken for granted since, oh, medicine was invented: The value of medical advice is in no small part a function of its independence. The people who did the study were so sure of its conclusions that, as one of them said, they expected that the league’s reaction would result only in some "quibbling around the margins of how it would actually be implemented." So what happened? The league’s senior vice president for health and safety, Jeffrey Miller, fired off an indignant 33-page rebuttal. I know what you’re thinking, Bill: "The NFL has a senior vice president for health and safety?" Yes they do! Although I think they keep him locked in the basement, with all the underinflated footballs.

Simmons: "Senior vice president for health and safety, NFL" is my favorite job description since "Vice president of customer relations, the Madoff Group."

Gladwell: Here is a direct quote from Miller. The Harvard report, he said …

Is this for real? Do we need to buy Miller NFL Sunday Ticket? Does he really think that players would be taking painkillers like candy if their prescribing physician weren’t working for the team? Has he never seen someone hobble off the field on one play and then miraculously reappear two plays later? Let me ask you this, Mr. Miller: When you negotiated what is undoubtedly a multimillion-dollar contract with the NFL, did you use an attorney supplied by the NFL? I didn’t think so.

So here’s my first suggestion: The NFL should let its players have their own doctors. Notice how I’m not asking for them to own up to the full physical damage the game inflicts on its players. That’s a 21st-century issue. Let’s just ask them to join the 20th century. Baby steps. Accept the principle of medical impartiality. By the way, do you know what the players association’s response to the Harvard report was? It "declined to comment." Oh man, DeMaurice. You’re breaking my heart.

Simmons: Shout-out to Oliver Stone’s Any Given Sunday for tackling that doctor-team conflict, painkiller abuse AND the concussion epidemic in a movie that came out in 1999. That same year, future cable classic Varsity Blues featured Billy Bob’s harrowing battle with concussions — the most realistic moment in a movie that featured stripping teachers, human whipped cream sundaes, and tackle-eligible Hail Marys. (I love that movie, by the way.) But yeah, these movies were released a good 10 years before the NFL acknowledged that, yeah, it might have a concussion problem.

Gladwell: Ten years? Please, Bill. The first public acknowledgement by the NFL that there might be a link between football and neurological problems like CTE came on March 14 of this year, when our good friend Jeff Miller finally conceded that fact while testifying before Congress. Any Given Sunday premiered on December 16, 1999. I think you meant to say "a good 16 years, 89 days before the NFL acknowledged that, yeah, it might have a concussion problem."

Simmons: No … no … no …

(PS: I’m just leaving these here: Real Sports, 2007 … Real Sports, 2009 … Real Sports, 2010 … Real Sports, 2012 … Real Sports, 2013 … Real Sports, 2013 … Real Sports, 2014 … Real Sports, 2015 … Real Sports, last month.)

Gladwell: By the way, I think it’s worth pointing out that Miller is a Mr. Miller, not a Dr. Miller. That’s right, the NFL executive responsible for player health and safety is not a physician. He’s a lawyer. More precisely, he’s an antitrust lawyer: Miller began his career as chief counsel for the Antitrust and Business Competition Subcommittee of the Senate Judiciary Committee. Honestly, you cannot make this stuff up. In response to a rising medical crisis on the football field, Goodell hired someone to make sure the rising medical crisis doesn’t cause Congress to take away the NFL’s antitrust exemption.

The weird thing about Goodell is that he doesn’t even make a pretense of doing things the right way. It’s like in Deflategate when he used the same law firm both to conduct the "independent" investigation and act as counsel for the NFL in the legal proceedings that followed. I mean, if you want to manufacture an entirely phony allegation against your most important player in defiance of all physical laws, why wouldn’t you at least try to make it look legit? The more I learn about the NFL, the more I want to crash one of their staff meetings. Just once. Be a fly on the wall. Roger at the head of the table surrounded by his coterie of admiring antitrust lawyers. What do you think they do, Bill? Does Roger just dump a big pile of cash in the center of the room, and then they take turns rolling around in it? Sorry. You were saying …

Simmons: What a perfect setup for my second fix! At Grantland, I pushed for 10-year term limits for every sports commissioner. Could they be reelected? Sure! But they’d have to run for reelection with players, owners, and fans each counting for one-third of the vote. Upon further review, let’s tweak that process to every eight years and time it with November’s presidential election. If Californians can vote for props like "Should we raise the cigarette tax by $2?" and "Should porn stars be forced to wear condoms?" — FYI: I didn’t make either of those up — then why can’t we vote for every sports commissioner? Can you imagine the glorious barrage of attack ads that Goodell’s competitors would have run? Wouldn’t you love to see the final electoral map with the pockets of Goodell voters? (He carried Texas? Dumb-asses!) Would the Russians hack the fans’ online vote to keep Goodell in charge just to piss us off? When President-elect Trump hires me as his sports czar, we’re going to have sports commissioner elections — I can promise you.

Gladwell: Gee. I dunno, Bill. If we had elections for NFL commissioner, we might end up with, say, a wholly unqualified reality-TV star with all kinds of dubious business connections and personal-conduct question marks who doesn’t understand football at all. I mean, what if the guy gets elected commissioner after we discover a tape of him boasting about a sexual assault? Or it comes out that he’s secretly being manipulated by Adam Silver? But that could never happen, right?

Simmons: You’re right, that’s definitely too unrealistic.

Gladwell: OK. My next fix. I watched two football games this weekend. On Saturday, Michigan–Ohio State and on Sunday, Jets-Patriots. First, a slight digression. In 2013, Ohio State spent $27 million on its football program and made $66 million. Michigan spent $25 million and made $91 million. The players I watched on the field on Saturday will, collectively, generate more than $150 million this season, of which roughly $100 million is pure profit. In return, they’ll each get a scholarship worth roughly $40,000 per year. This whole "amateur" business is getting a little embarrassing, don’t you think?

Now, two quick thoughts. First, my favorite bit of doublespeak on all of this comes from the NCAA, which says in the FAQ section of its website: "The collegiate model of sports is centered on the fact that those who participate are students first and not professional athletes."

Did Jeff Miller write this? It makes no sense. An amateur is someone who is unpaid and operating in a world in which payment is not possible or relevant. I am an amateur runner. Why? Because there is no money at stake in local masters road races. But if The New Yorker, which makes lots of money, didn’t pay me for writing articles, I wouldn’t be an "amateur writer." I would be a sucker. Big difference. Every time a multibillion-dollar enterprise like the NCAA refers to "amateur" football players, then, what it means is football players who, for the association’s own selfish, greedy reasons, it has chosen not to pay. And the correct understanding of that statement about the "collegiate model of sports" is more like: "the collegiate model of sports is centered on the fact that those who participate are unpaid, and we cannot pay them because then they would no longer be unpaid." Whenever we wonder where the NFL owners got some of their more antiquated notions about compensating and treating athletes, the answer should be simple: They learned it in college.

But here’s the other thing. Ohio State–Michigan was a thousand times more entertaining than Patriots-Jets! Even someone like you, Bill, who sleeps under a giant Fathead poster of Tom Brady, has to admit that. The Saturday game had Jim Harbaugh throwing his playbook in the stands, the fans going insane, Ohio State going from hapless to unstoppable in the space of half a quarter, and one of the greatest overtimes in living memory. (How much do I love the 25-yard-line back-and-forth?) The Sunday game had an expressionless Belichick, a glum Brady, Gronk limping off for his weekly visit to IR and a Jets team that meekly laid down and died in the fourth quarter. Can we please inject just a little more life into the pro game? The best moment of Ohio State–Michigan came when we got a glimpse of a bunch of Cleveland Cavaliers on the sideline, dancing, during one particularly Ohio State–ish moment. Can we have more dancing in the NFL please? More excessive end zone celebrations? More outlandish quarterback-sack routines? (I never thought I’d say this: I miss Mark Gastineau!) Can we get rid of instant replay, just so we can have more pissed-off fans and more furious postgame rants, like Harbaugh’s epic explosion after the game? The NFL has effectively turned into a circus: a bizarre combination of feudal management practices and primal on-field violence. If you aren’t going to fix either of those things — and I’m not going to hold my breath — then can we at least have some fun?

Simmons: "Feudal management practices" + "primal on-field violence" = "why the UFC just sold for $4 billion." You think NFL players are exploited? Did you know that UFC fighters are independent contractors? There’s no UFC union! In fact, a fighter could train for UFC fights by day and drive an Uber at night and double his chances to never belong to a union. I’d say that counts as an exploitation of athletes. Although the UFC is miles ahead of boxing. That reminds me, I have a quick tangent for you …

On Saturday night, HBO aired a potential Fight of the Year candidate: undefeated slugger Nicholas Walters taking on Ukrainian super-featherweight/two-time gold medalist/possible wildebeest Vasyl Lomachenko (he’s the LeBron of boxing, only he hasn’t gone mainstream yet). So Loma spends the first seven rounds toying with a helpless Walters and peppering him from every angle because, again, he might be a fucking wildebeest. Before the eighth round, what happens? Walters quits. He pulls a "No Más."

When Max Kellerman interviewed him afterward, Walters basically admitted, I was too rusty, it was only gonna get worse, I didn’t want to take any more punishment, I’ll get him next time. In 2016, with everything we know now … can you blame him? Walters knew he couldn’t beat Lomachenko, so he considered all the brain cells he’d already lost and all the brain cells he was clearly about to lose. He realized it wasn’t worth the risk. I continue to think 2016 is the weirdest year ever — now we have undefeated boxers quitting fights after seven rounds because it’s a good career move, and actually, IT IS.

Gladwell: In dogfighting, they refer to the best dogs as being "game," meaning they are willing to fight to the death. What you’re saying is that we are finally at the moment when fighters no longer feel compelled to be as "game" as dogs. Progress, Bill!

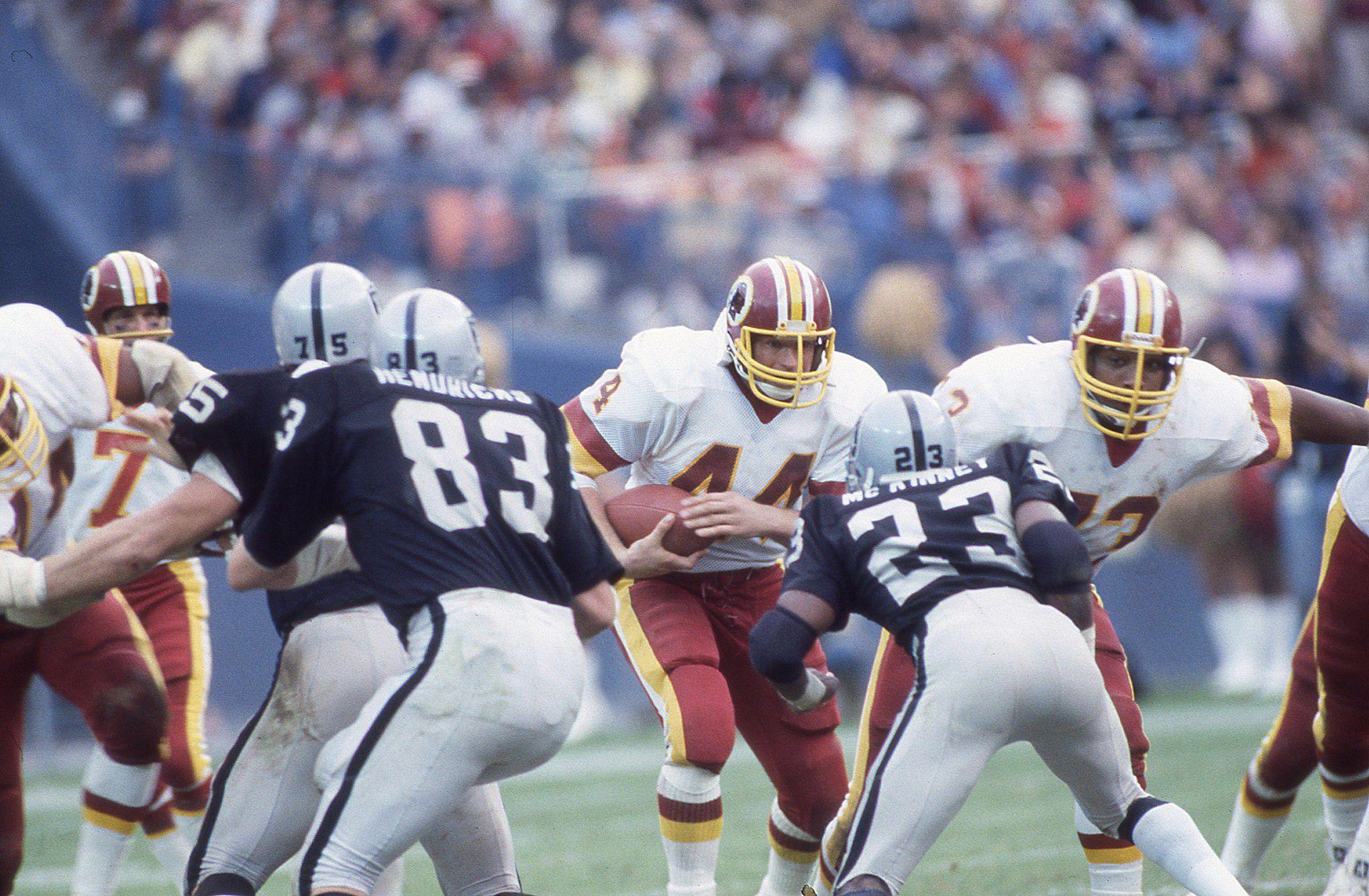

Simmons: My next football fix: weight limits. Check out the average weights of Washington’s starting offensive lines in the 1980s ("The Hogs") and now ("The Monster Hogs").

Washington (1982): 273 pounds

Washington (1988): 279 pounds

Washington (2016): 326 pounds

They weigh 53 pounds more per person than the ’82 Hogs! It’s not like 1982 was THAT long ago. That was the year Michael Jackson released Thriller, Eddie Murphy became a superstar and Michael Jordan made the championship-winning shot for North Carol — you’re right, that was a long time ago. But still … 53 pounds? How is this good? How is this healthy?

You’ll love this: 2016’s "smallest" offensive line belongs to the Falcons … at a paltry 304.4 pounds per player. (FYI: This link is amazing.) I see two major issues here that don’t include the words "obesity," "heart attack," "cardiovascular disease" or "steroids."

First, it’s telling that so many linemen either drop 50–70 pounds after they retire OR swing the other way and balloon dangerously higher because they can’t change their eating habits. Do you realize how much you have to eat to maintain a 300-plus-pound weight? Matt Birk claims he consumed 6,500 calories a day, sometimes tripling up on dinners because that’s a totally normal way to live. Jeff Saturday dropped 60–70 pounds and fell under 240 after he retired; watch Jeff on ESPN every week and ask yourself, "Wait, this guy weighed 25 percent more five years ago and it was a GOOD thing for his athletic career?"

Second, I’m guessing that oversize linemen who carry an extra 30–50 pounds present a bigger injury risk to themselves and others. It’s just one of my crazy theories. And it’s an easy fix. Again, weight limits. When they had the tug-of-war in the Olympics, and later, in the just-as-important Battle of the Network Stars, there was a weight limit for each team, 1,500 pounds, which you could divvy up however you wanted. I don’t think that’s realistic with football. But if no offensive or defensive lineman could weigh more than 300 pounds, no tight end or linebacker could weigh more than 250, and no defensive back or skill-position player could weigh more than 240 … would the sport be safer? Absolutely! Right until some 6-foot-8, 330-pound left tackle sued the league for discrimination and my whole plan got shot to hell. Dammit.

Gladwell: Remember 10th-grade physics, Bill? Force equals mass times acceleration. You’re absolutely right. There is no way to reduce the forces that cause so many injuries without reducing the mass. (I’m not sure there’s much to be done about acceleration.) While we’re on the subject of offensive linemen, I want to quote a (ridiculously long) section of a March 1 article from ESPN.com about the Buffalo Bills. I chose it at random:

You and I and every other football fan in America have read so many stories like this over the years that I think we’ve lost sight of how weird they are. Here we have an account of consequential decision-making by a professional sports franchise — an organization in the business of creating and sustaining a high level of athletic performance — in which there is no consideration whatsoever of what it takes to create and sustain a high level of athletic performance. It’s entirely about money. The Bills propose to say goodbye to Kraig Urbik and Mario Williams, the article states, because they can’t afford Kraig Urbik and Mario Williams.

Now of course this isn’t true. The Bills can afford Urbik and Williams. The owner of the Buffalo Bills is Terry Pegula, who sold his natural gas company a couple of years ago for almost $5 billion. Like eighteen of his fellow NFL owners, he’s a billionaire! He could have found the necessary cash for Urbik and Williams in the loose change on the top of his dresser. Pegula, in fact, may have been perfectly happy to re-sign Urbik and Williams. Maybe he thinks his team would be better with them in the lineup than it is with their replacements. Maybe he’s perfectly willing to spend a few extra dollars for a chance at making the playoffs before he dies. And maybe he just wants to make his fans happy. And why not? It’s been nothing but bad news for Buffalo since William McKinley was assassinated in 1901.

Simmons: I disagree. Buffalo created buffalo wings in 1964. Teressa Bellissimo is an American hero. Sorry, keep going.

Gladwell: A better way of saying it is that Buffalo can’t afford Urbik and Williams under the terms of the arbitrary salary restrictions that the owners have collectively imposed upon themselves. Now, what the owners tell us is that those arbitrary restrictions exist explicitly to help small-market franchises like the Buffalo Bills compete on a level playing field against major-market teams in places like New York City and Los Angeles. But that’s not quite right either. There’s nothing stopping the owners from sharing their revenue. If they wanted to, they could throw every penny all the teams earn into one pot and split it 32 ways. Problem solved. What they really mean is that Urbik and Williams were cut loose from the Bills because the team could not afford them under the terms of the arbitrary salary restrictions that the owners have collectively imposed on the players, because they would rather not impose any restraints on themselves.

Can you imagine if any other industry tried to pull this stunt? The average market salary at Google is $243,000 a year; at Yahoo, it’s $203,000 a year. What if Google’s Larry Page and Sergey Brin called an emergency all-hands meeting, and asked their employees to take $40,000 pay cuts so that all the companies involved in online search could compete on a "level playing field"? People would stop working at Google: One of the ways in which companies in talent-driven industries compete against each other is by making their own choices about whom to hire and how much to pay them. If there were a salary cap in Silicon Valley, there would be no Silicon Valley.

I have no idea why the NFL thinks this problem doesn’t apply to the league. Urbik is by no means a great player. He’s a career backup. But he knows the system, and he knows his teammates and I’m quite sure that as whoever took his place learned the ropes, blocks were missed and sacks allowed and what might have been 5-yard runs turned into 2-yard runs — and if you are a Buffalo Bills fan your enjoyment slipped by the same amount. It’s the same point you were making earlier about Vince Wilfork. If playing good football were the only consideration, the Patriots would almost certainly have kept him. Item no. 3 on your list of secondary NFL conversations — the decline in the quality of play — is an entirely self-inflicted wound. You want a better game? Free Terry Pegula! Let him spend as much on players as he wants!

Simmons: I think the words "Free Terry Pegula" are a sign that we should wrap this up soon. For the record, I would decrease taunting penalties to 5 yards (how is taunting someone as dangerous as a chop block, a helmet-to-helmet hit or one of those semi-decapitation face mask penalties?), make helmet-to-helmet hits reviewable (isn’t that the natural evolution of pretending to care about head injuries?), put microchips in footballs (for all the reasons you’d think) and dump celebration penalties and taking-your-helmet-off penalties (because the league clearly enforces anonymity so that it can keep control of its pay structure and balance of power, which is actually a little creepy when you think about it). But here’s a bigger idea that would easily shave 12 minutes off every game (and work for every sport, by the way) …

Did you know NFL games have ballooned to three hours and 12 minutes on average this season? That give us 60 minutes of actual football and 132 minutes of commercials, challenge flags, instant replays, timeouts, injury timeouts, two-minute warnings, injury cart pickups, penalty announcements, awkward closeups of The Guys In The Booth, first-down measurements, icing-the-kickers, highlight breaks, streakers whom they never show running across the field, and promos for CBS comedies featuring white dudes in their 40s and 50s.

So how could we fix it? During NBA telecasts, you’ll notice ESPN occasionally pulling away from a free throw attempt, switching to a wide shot of the arena (so you can still see the free throws) and promoting an upcoming ESPN program with an in-game ad. Never bothers us, right? Same for Sunday Night Football showing four different starting lineups in the first quarter — "Tom Brady, quarterback, University of Michigan" — with each one running about 25 seconds so that viewers never miss a play. You know why these in-game gimmicks work? Widescreen televisions. We have enough real estate to accommodate split screens now. Gladwell, that’s our 12 minutes of fat, right there! If they sold 36 20-second ads, they could sprinkle in nine per quarter during various breaks/stoppages/replays/hiccups and we’re good to go. Move this shit along.

Gladwell: Yes please. What’s the most exciting stretch in any football game? When a team gets the ball with two minutes remaining, down a touchdown and with no timeouts left — because that’s virtually the only time in the entire game when we get continuous action. Football played in a hurry is really exciting. We need more of it.

Simmons: Same for basketball. There’s a reason everyone loves the flow of those FIBA games.

Gladwell: OK. Here’s my next one. I want to go back to what DeMaurice Smith said: that the owners know that the threat of a player strike is hollow. There are two reasons for that. The first is that the players are unwilling to make that sacrifice. But the second is equally important: There’s a very real worry on the part of the players association that the fans won’t make that sacrifice, either — that in the event of a work stoppage the fans will side with the owners. Is that true? I fear it is, and it breaks my heart. One of the responsibilities of being a sports fan, I think, is to align your interest with the athletes. I know all the reasons people don’t like to do that: The athletes are spoiled, overpaid, arrogant, etc. Bullshit. A group of young men create an extraordinarily beautiful game through their own talent, discipline, and creativity. They quite literally risk their lives and long-term health in the process. Their efforts create billions of dollars of wealth for the league, which responds to that windfall by giving the players, over the past several collective bargaining agreements, a smaller and smaller share of the pie. Yet the players are afraid to take the only step available to better their lot. Why? Out of a fear the fans will side instead with the rich, mostly white, male billionaires lucky enough to have been let in on the cartel that is the NFL. Oh man. Is that where we are as a society?

Simmons: Short answer: yes. Long answer: yes. (By the way, I like when you call the 32 NFL owners a "cartel." I’m stealing that.)

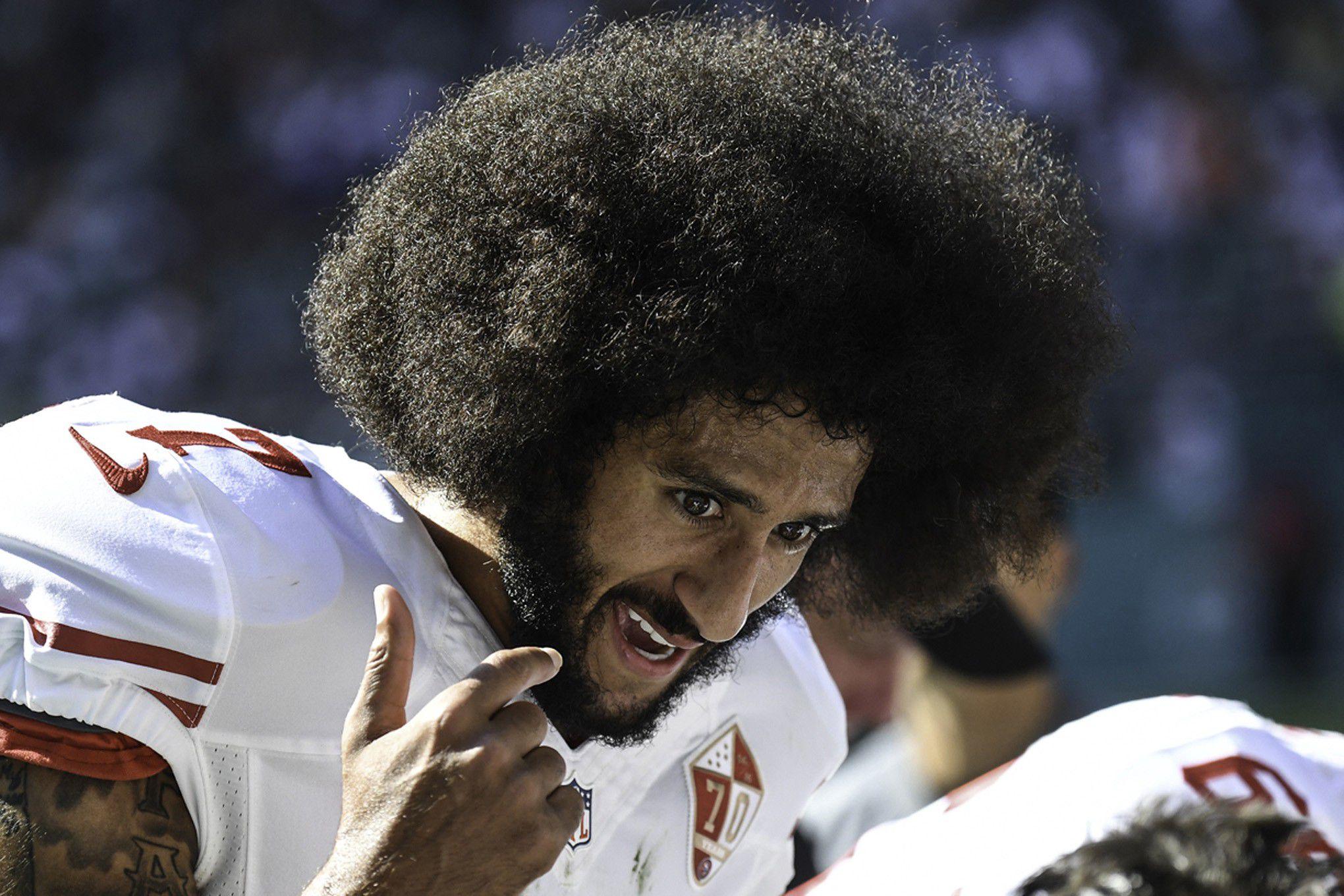

Gladwell: There was an article earlier this year on the Colin Kaepernick saga by Bleacher Report’s Mike Freeman that quoted a senior league executive as saying that Kaepernick was as despised among NFL officials as Rae Carruth. That’s Rae Carruth, the Carolina wide receiver who arranged the murder of his pregnant girlfriend. "In my career, I have never seen a guy so hated by front office guys as Kaepernick," Freeman quotes one general manager as saying.

Now, I get that some people disagree with Kaepernick’s stand, or how he chose to behave, or the way he articulated his position. I also get that the nameless executive is probably exaggerating a bit for effect. Fine. But at the end of the day, Kaepernick is an intelligent young man at least trying to address something of consequence: the continuing disgrace of racial inequality in this country. And, incredibly, some portion of the people running football find that appalling. So here’s what I want, with my final suggestion. I want football fans to stand up and say that they’ve had it with the cretins running the league. And I want football fans to pledge that whenever a player tries to make the game or the world outside the game a better place — no matter how awkwardly or inexpertly they go about doing it — they’ll have his back.

Simmons: I didn’t believe that anonymous Carruth-Kaepernick quote until I started considering the reasons an NFL executive might have said it. Though if Carruth goes down as a first-ballot NFL Scumbag Hall of Famer, he never threatened revenue, ratings, locker rooms or the league hierarchy itself. We’ve spent the past half century becoming conditioned to NFL players behaving poorly. Aaron Hernandez, Leonard Little, Christian Peter, Dave Meggett, Ray Rice, Darren Sharper, Tyreek Hill … you can keep rattling off offenders for days. The most heinous human behavior possible never actually affected the NFL’s bottom line, right?

But Kaepernick’s anthem stance affected the NFL’s business. Kaepernick injected discussions about politics and racism into the 2016 season in the simplest but most profound way possible. He also triggered the wrath of football fans in certain pockets of America who feel so strongly about the American flag, and what they believe it stands for, that they became one of the excuses for declining ratings (whether it’s true or untrue). And worst of all for owners and executives, Kaepernick threatened the team-over-individual mind-set that’s unique to football and has undeniably been modeled after the military since the days of leather helmets and no face masks. The NFL doesn’t want fractured locker rooms. The NFL doesn’t want its players behaving in ways that it can’t govern — it can penalize Kaepernick for ripping his helmet off after a touchdown, and it can penalize him for doing the macarena with his tight end, but it can’t penalize him for kneeling during the national anthem. For the NFL, irredeemable players like Carruth or Hernandez were outliers — a necessary cost of doing business with a certain type of dangerous person who might thrive in a barbaric sport. Kaepernick is no outlier. He exposed a precarious political-racial-social tightrope that the league had been walking for decades. Rae Carruth never exposed anything.

Anyway, I admire your hopefulness, but we can’t get America to agree on anything right now. We can’t even stop billionaires from making the general public pay for stadiums they don’t need … we’re gonna fix football? Did you see that the Rangers made everyone in Arlington pay for ANOTHER new baseball stadium? They just built one in the mid-1990s, during the post–Camden Yards boom, and now they’re building a new one because they wanted air conditioning. And a majority of Arlington residents voted for it! Over, like, paying for things Texas residents might actually need! It’s hopeless, Gladwell. We’re never fixing anything.

Gladwell: Since we’re ending on a depressing note, can I pass on the link you sent me at 5 a.m. last night? It’s from Neuroscience News. (By the way, everything we need to know about football’s second-conversation problem is summed up by the fact that Bill Simmons, fanatical football fan, is reading Neuroscience News at five in the morning.)

Ready?

If I were Roger Goodell, I’d get an antitrust lawyer on this as soon as possible.