When Michael Irvin wore a stocking cap in the remake of The Longest Yard, even Adam Sandler thought it made him look hard. "It criminalized me," Irvin said, with the air of a man who knows what that’s like. He now refuses to wear caps on TV, ever. So one night in December, as the temperature dipped toward freezing, Irvin stood shivering outside Seattle’s CenturyLink Field. When he looked up toward the stadium lights, he saw that snow had begun to fall.

Irvin did not much mind. A crowd had gathered behind the set where the NFL Network was filming its pregame show. During a commercial, Irvin had thrown himself into it. "Shaking hands and kissing babies," said Steve Mariucci, Irvin’s NFL Network colleague. "Michael’s a man of the people."

Years ago, when Irvin started traveling to remote broadcasts for ESPN, fans who remembered the bludgeonings that the 1990s Cowboys put on their teams would gather to chant, "Dal-las Sucks!" "They never said anything to Steve Young …" Irvin noted drily. "Maybe it has something to do with the way I was playing, all the stuff I was doing."

Over the intervening years, the reaction turned. It’s no exaggeration to say that among the people who stand in the cold outside TV sets, Irvin is now one of the most beloved ex-players in the NFL. "None of these kids saw him play in 1994," said Mariucci. "But his persona is even bigger now from television."

"How ’bout a smile, Michael?" someone in the crowd yelled.

"You can still play!"

"What these hands do now is just carry SUPER BOWL RINGS!" Irvin shouted back. Not that he wears them. Players who have one Super Bowl ring always show it off, Irvin has said. Players who have three rings don’t bother.

Eyeing the crowd like a Secret Service agent was a big man in a wide-brim felt cap and blue-suede shoes. This is Rassaun Johnson. At remote broadcasts, Johnson guards Irvin’s person, carries his valise, and — on one occasion I observed — bends down to tie the laces on Irvin’s Ugg boots.

"We have to keep him moving," Johnson said, "because otherwise Michael will stay and talk to literally everybody in the stands."

Irvin’s colleagues Mariucci, Marshall Faulk, and Rich Eisen stood nearby. They did not have bodyguards.

By December, the Cowboys were cruising toward a 13–3 regular-season record. Irvin had assumed his natural role as the team’s ambassador to the world. He’d been preparing rookie quarterback Dak Prescott for the spoils of fame he enjoyed in the ’90s, when the Cowboys had to enter every hotel through the back door, when Irvin could walk the streets of Dallas and feel like the biggest movie star in the world.

"Just think about it," Irvin told Prescott. "If you lead the Cowboys to a Super Bowl, do you know what you would be in African American history? It would go Barack Obama, Dak Prescott."

"And in some homes in Texas, it’ll be Dak Prescott, Barack Obama!" Irvin laughed his famous hoarse laugh. "Heh heh heh."

In person, as on television, Irvin toggles between studio-show inanity and New Testament righteousness — as if Terry Bradshaw and a televangelist were battling for his soul. TV, Irvin has said, is a form of ministry. "When can you really talk to men?" he told me. "Where do men really receive things? They receive them through sports."

After snapping a few selfies, Irvin asked the crowd, "Where are the fathers and sons?"

He located a pair: a cherubic boy of 4 or 5 and his unshaven, hipster dad. Irvin began ministering. His topic was fatherlessness — "a curse," he said, "that’s killing this country."

To the dad, Irvin said: "Your commitment as a father is to never leave your seed" — a.k.a, the boy.

The dad nodded. Sure, Playmaker.

Irvin then turned to the boy. The boy was at least a decade away from procreating. Irvin was undaunted. "Don’t ever let your kid come and hunt me down and say he can’t find his dad," he said. "If he does that" — Irvin placed his hands around the boy’s neck and comically began to shake him — "then I’m going to come and kill you!"

After Irvin returned to the set, the dad and the boy had the happily glazed look you get after meeting a celebrity. Someday, perhaps, they would talk about the moment: Remember that Seahawks game — the one where Michael Irvin told us not to be deadbeat dads?

Michael Irvin is 50 years old. The number on the scoreboard doesn’t scare him. It’s 51 that scares him. Irvin’s father, Walter, was 51 when he died. "That’s something that haunted me forever," Irvin said. "I can’t wait to hit 52." A few years ago, he started putting his affairs in order just in case.

It’s no surprise the Playmaker is still famous. Such is the power of sports TV (Irvin is on the NFL Network and Showtime’s Inside the NFL) and its in-house nostalgia factory (The U was a 30 for 30 tribute to Irvin’s old Miami Hurricanes).

What’s surprising — if you remember the years of drug arrests and scandals that Irvin calls "my mess" — is that Irvin is now an elder statesman. After his pregame duties in Seattle ended, Irvin sat in a trailer that doubled as the Thursday Night Football green room. He looked through Versace sunglasses at Eisen, Bob Costas, and other broadcasters. "When I was a player — and unfortunately I was in my mess — these were the guys giving the commentary on me," Irvin said. "Now, I’m sitting here with ’em."

For young Cowboys like Prescott and Zeke Elliott, Irvin is a chatty mentor — Uncle Michael. Cowboys owner Jerry Jones told me, "If in fact we have a player with a unique set of circumstances" — a record like Irvin’s, say — "I’m really aggressive in getting Michael to spend some time with him."

Ironically, it’s Irvin’s sins that now confer gravitas upon him. "I joke sometimes with people," Irvin said. "I say, ‘Who would you rather give you help on this: Dr. Phil, who just read about it in a book, or a man like me, who actually walked it?’ Heh heh heh."

Irvin’s public rehabilitation had yet another iteration. His life has been reshaped into a Christian parable. The Playmaker has become the Praymaker. Over dinner at a waterfront restaurant in Seattle, Irvin bowed his head before digging into his king crab legs. In the Thursday Night green room, I noticed Irvin sitting alone for a time, thumbing through a devotional.

A pupil of Dallas evangelist T.D. Jakes, Irvin is fond of saying that every church needs Lazarus. For the reanimated man proves the validity of the ministry. This is no less true of the NFL, where Archbishop Goodell wants not just to punish wayward players but — after suspensions are served and fines paid — have them return to the fold to counsel their peers.

It’s tough to find a famous player willing to accept such a role. This is where Michael Irvin comes in. "I like to raise my hand and say, ‘I’m your Lazarus,’" he said. "Somebody you brought back from the dead."

If Michael Irvin was a sinner, he was an undeniably charming one. I got a taste of this over dinner in Seattle. Every time Irvin cracked a joke, he took his giant right hand — the one that he used to shove Darrell Green aside without ever drawing a pass interference call — and extended it across the table for me to shake. The first time I shook it sheepishly; by the sixth or seventh handshake, it was like Irvin and I had been shaking hands for years. It was a typical love bomb. "If I ran into him on the street in Dallas, he’d be hugging me and kissing me on the head," said his old teammate Darren Woodson, who was one of multiple Irvin pals who told me he often kissed them on the head.

In 2013, Rich Eisen and his wife, Suzy, needed a friend to speak at their daughter Taylor’s baby-naming ceremony. They both agreed it should be Irvin. This produced the surreal scene of a rabbi throwing the ceremony to the Playmaker. Irvin began with a joke. "Everybody thinks I’m Jewish because they think my last name is Irving," he said, while 1,000 Catskills comedians died of shock.

Last week, while the Cowboys were on a playoff bye, I called Jerry Jones. Without caveat, Jones declared Irvin to be his favorite former player. "I love him because I see so much of me in him," Jones said. "In that a lot of what we are overcoming are our foibles. I’m a guy that’s used eight of my nine lives."

Witness Jones’s "all-time favorite" Irvin story — a story no other NFL owner would tell about any other player. In the mid-1990s, Irvin and some Cowboys teammates rented a house near their practice facility that they called the White House. It was your basic den of iniquity — though the players insisted they were taking the carousing they did across the city of Dallas and bringing it under one roof. You know, for safety and convenience.

The White House’s existence became public in 1996. "I called to ask Michael to get out of a meeting and come into my office," Jones said. "When he walked through the door, I unfolded the big paper in front of him and said, ‘What do you have to say about this?’"

Another player might have hedged. But Irvin "didn’t blink. He looked at me and said, ‘Jerry, this is a classic case of trying to do the wrong thing the right way.’ Now, how can you stay mad, or how can you not love that answer?"

Beginning in the mid ’90s, Irvin’s "mess" sprawled from the sports pages to the news pages. He was arrested three times in five years for drug possession (one arrest resulted in a no-contest plea; the other charges were dropped); he reportedly stabbed Cowboys teammate Everett McIver in the neck with a pair of scissors.

This is a necessarily partial list, because Irvin lived in a world uncatalogued by social media. "Can you imagine Twitter every second?" he told me. "Are you joking? I got in trouble with News at 11:00."

You can trace the "new" Irvin — the man who hears God’s voice and sees His signs all over Dallas — to an event in 1996. Irvin was driving to a hotel to meet two women, neither of whom were his wife. Suddenly, Irvin told me, he heard a voice. It was his mother, Pearl. "Don’t go in that hotel," she said.

Irvin went into the hotel. A while later, Dallas police entered the room the women were in and found Irvin with cocaine and marijuana. Irvin was arrested for drug possession.

The arrest was a sensational media event in Dallas. As he drove home from jail, Irvin prepared to charm his wife as he would Jones. "I’m a talker now …"

Before Irvin could say a word, Sandy told him she wasn’t leaving him. "I’ve already heard from God," she said. "I am your wife. You need to go make your peace with God."

Irvin was staggered. "She took the fight from between me and her, where I thought, Oh, I got a shot to convince and confuse her …" he said, "and she put the fight between me and God, where there is no winning for me. It really was brilliant, actually."

And — so goes the parable — the man had to get right with his Maker. In this case, the man being the Playmaker.

On TV, Irvin sits on the far right edge of the desk for the same reason Charles Barkley does. That’s where studio producers put their "energy" guy — the one who needs no help getting to the center of the frame. Barkley chews scenery with his old-man lectures; Irvin is more prone to wearing a ninja outfit. "A lot of times you have to pull things out of some on-air talent," said Mike Muriano, an NFL Network production executive. "With Michael, a lot of it is, ‘OK, save it!’"

Last Saturday, I went to the NFL Network headquarters, in Culver City, for the last hour of a marathon, four-and-a-half-hour pregame show. "Football isn’t Walter Cronkite," Irvin told me by way of a theory of broadcasting. Indeed, GameDay Morning owes more to a children’s variety hour, with the stage manager herding ex-players to and from cutely named segments ("Warner’s Corner," "U Know It"). After a time, I noticed Irvin sitting at the edge of the desk filming himself with a selfie stick.

When Irvin first got on TV, in the early 2000s, he was accused of playing a character — one that embodied the pregame-show mantra of hyena laughter and forced zaniness. (It was appropriate, if unfortunate, that Irvin was nicknamed "the Producer Seducer.")

The bit about pregame shows is true. (Producers will tell you this is exactly what the audience wants.) But spend some time with Irvin, and you realize he’s innocent of the charge of playing a character. There is no public and private Michael Irvin. "He’s in his natural habitat," said his old teammate Emmitt Smith.

"What you see with Irv on TV, man, I saw the seven years I played with him," said Woodson, who now works for ESPN. "He’s the same guy all the time."

When it comes to malapropos, Irvin’s historical comp is probably the Game of the Week’s old word mangler, Dizzy Dean. Irvin once snapped a picture with the NFL Network’s Cynthia Frelund with his selfie stick, then tweeted, "I simply love pulling my stick out around you." A Twitter pile-on followed. Hearing Zeke Elliott talk about rushing, Irvin told a Dallas radio station this fall, "makes me want to go in the bathroom and spend some time by myself."

"I need another locker room," Irvin told me, nodding at his colleagues, "and this is what it is." Even ex-players are competitive. If Irvin doesn’t wear his Super Bowl rings, his colleagues joke that at some point during every on-air argument, no matter its subject, Irvin will remind them that he has "THREE SUPER BOWL RINGS!" I heard it as Irvin sat with Kurt Warner and Marshall Faulk in the "Players Only" segment: "I was fortunate to win THREE SUPER BOWLS IN FOUR YEARS …"

This is partly Irvin’s own self-preservation. He played before the passing boom inflated every receiver’s stats. But Smith noted that it’s also a subtle green-room status marker. The athletes who get TV gigs are usually among the best who ever played. Irvin is reminding them that he has more hardware.

Irvin found God in Deion Sanders’s bathroom. It was 1997 or thereabouts. Irvin had gone in to take a leak, and the evangelist T.D. Jakes, who was at Sanders’s house leading a Bible study, walked in on Irvin and began to witness to him. "He initially acted like he wasn’t interested," Jakes said. "He was a pretty wild guy at the time." Irvin told me he wasn’t ready for salvation. He ran out of the bathroom.

Jakes is a round man with a shaved head and a gray goatee. Emmitt Smith, who worships at the Potter’s House, said when Jakes speaks, it seems as if he has been hiding in your closet, eavesdropping on your conversations. Jakes also has a gift for purple rhetoric to match Irvin’s. His sanctuary is a "labor room," he once said, for worshippers "pregnant with destiny and pregnant with dreams."

Jakes has said that he was advised against taking on Irvin as a pupil by people who thought Irvin would take advantage of him. But their friendship proved mutually beneficial: Irvin attained spiritual salvation, and Jakes’s ministry attached itself to the ’90s Cowboys. These days, Irvin calls Jakes "Daddy" — a name for a spiritual father.

It was Irvin’s conclusion that his "mess" sprawled out of control because he didn’t have a father to submit to. Irvin’s dad, Walter, died when Michael was 17. George Smith, his high school coach, was a capable fill-in for a time, as was Jimmy Johnson, Irvin’s coach in Miami and Dallas. But Irvin couldn’t bring himself to call Barry Switzer or Chan Gailey "Dad." "I call that my fatherless period," Irvin said. Thus, he ministers to Seahawks fans about deadbeat dads, and he calls mentees like Dez Bryant "my son."

Jakes was Irvin’s confessor, promising to never divulge Irvin’s darkest secrets. "If he got into trouble," Jakes said, "he would tell me exactly what it was and what happened, and I kind of would work him through it."

"You can’t lie to him," Irvin said. "He has those eyes that you swear he’s just right in your soul ringing bells. Like he’s knows everything that’s going on in there."

What was amazing was how much of Irvin’s confessions dribbled into public. The TV studio became the Potter’s House. Irvin is surely the only NFL player to hint at adultery in his Hall of Fame speech. When he was on Fox Sports Net’s The Best Damn Sports Show Period, he talked freely of his womanizing even as he refused to speak the show’s title, lest he curse in public.

In the Thursday Night green room, Irvin lowered his voice only slightly when he told me of his old adventuring: "If I was with two women, I wanted to have four. With four, I wanted to have six. It got out of hand. I look back and think, ‘Thank God I got caught. Thank God I got caught when I did.’"

For Jakes, Irvin’s religious salvation prefigured his PR rehabilitation. "The more you get closer to God, the less public scandal you have," he said. In 2000, Jakes advised Irvin to humble himself before Fox executives after he lost his job when police found him in yet another apartment with drugs. Eventually, none other than Pat Summerall — a former NFL star who dealt with an alcohol dependency and found God himself — vouched for Irvin with Fox brass.

For all of Jakes’s spiritual work, Irvin did the PR heavy lifting himself. Even as a televangelist, Jakes was dazzled by Irvin’s magnetism — the way he could win over the skeptical. "They always liked him," Jakes said of Cowboys fans. "Even when he was in the middle of all his chaos and womanizing and all the drugs. … He’s just a likable guy."

A green room is a great place to watch a football game, because all the false politeness you hear on TV melts away. When Richard Sherman pulverized Jared Goff, sending him into the concussion protocol, nobody in Seattle adopted the somber tone of an Outside the Lines report. The announcers said, "Ohhhhh!" just like the folks scoring at home.

When NBC put up a picture of Jeff Fisher, who the Rams had fired that week, eyes rolled. As Al Michaels and Cris Collinsworth talked about Fisher’s replacements on TV, Irvin turned to Tony Dungy, the coach turned studio host, and asked, "What you gonna do if you get that phone call?"

Irvin’s value to sports TV goes beyond his zany personality. This season, the NFL was mired in a ratings slump. Yet Dallas Cowboys games often matched or exceeded the ratings of games that aired in the same time slot in 2015. The Thanksgiving Day Cowboys-Redskins game drew 35 million viewers, the most of any regular-season game in Fox’s history.

Just as CNN hired Jeffrey Lord and Corey Lewandowski to defend Donald Trump, it has become de rigueur for sports cable channels to have Cowboys surrogates. On FS1, Skip Bayless calls them "my Cowboys"; when the longtime Dallas radio host Norm Hitzges talks about the team, he often assumes the second-person "we."

Irvin anticipated this. When he started with Fox, he brushed aside the mantle of impartiality that was pressed on ex-jocks. "For years, you couldn’t say you had a team," Irvin said. "I was one of the first to say to people, ‘I’m not lying to you. I’m not coming on acting as if I’m not a Cowboy fan.’" He figured it made him much more like the fans at home, who would never dream of being impartial.

"I always tell people it’s tougher being a fan than it was playing," Irvin said. "When it ended as a player, you’re exhausted, tired. You really just wanted to get away from it and just let it go. As a fan, you’re not tired. My mind is just like, ‘This should have happened. We should have done this.’"

When the Cowboys go 13–3, their ambassador enjoys certain downstream benefits. Groups hire Irvin to give speeches, and he gets some commercial work. "It makes it more difficult to get through the airports and stuff like that," Irvin said, a smile spreading across his face. "But it is more profitable also."

Irvin’s cachet is further increased by the fact that his Cowboys teams have never produced an heir. Since 1996, when Irvin walked off the field with that THIRD SUPER BOWL RING, the team has won just three playoff games in 20 years.

In Dallas, the ’90s Cowboys are nostalgia — a piece of sports IP in a constant state of reboot. Fans immediately dubbed Dez Bryant, who wears no. 88, the "next Michael Irvin." This season, Dak Prescott was pronounced the "next Troy Aikman" (following Tony Romo, the old next Aikman), and Zeke Elliott was called the "next Emmitt Smith."

How does it make you feel, I asked Irvin, to constantly watch them try to replace you?

Irvin said: "People tell me, ‘Michael, why don’t they retire your jersey?’ Why would I want my jersey retired? When they retire it, the only time they talk about it is when I leave time and go to eternity and they take the camera off the field and say, ‘Hey, we lost Michael Irvin today. Back to the game.’

"Why should I wait for my death for my flowers? With Dez Bryant wearing [88], every Sunday when he makes a play, they say, ‘Boy, that reminds you of Michael Irvin!’ If he a drops a ball, they say, ‘Michael Irvin wouldn’t have dropped that!’"

Irvin smiled again. "I get to enjoy my flowers every Sunday," he said, "while I’m alive." Then he shook my hand.

Just before halftime, Irvin and Rassaun Johnson left the green room and made their way to the field. Irvin had a halftime show to perform on, but as soon as he walked out of the tunnel, huge swaths of the Seahawks crowd stopped watching the game and starting yelling for him. Irvin never played an NFL game in Seattle.

A man wearing a Santa costume who was sitting in the first row grabbed Irvin. He fumbled with his camera phone as Irvin waited patiently, a camera-ready smile plastered across his face. Johnson had pulled Irvin away so he wouldn’t miss his TV hit.

Later, on the sidelines, Irvin chatted with Howard Schultz, the former Starbucks CEO. "He said, ‘Man, what a great career you had,’" Irvin reported later. "I said, ‘What a great career you had!’" Imagine that conversation taking place in 1997.

If Irvin is beloved, part of it can be chalked up to the way the passage of time glamorizes everything. In the ’90s, the sins of Irvin’s Cowboys were seen as evidence of their rotten souls. Now, they’re a vital part of the Cowboys’ mystique.

"Same thing at Miami," Irvin said. "When we were in it, we were the worst people in the world. Now, it’s the most-watched 30 for 30 they’ve ever done."

But another part is that Irvin’s particular idea of redemption — the public accounting of sins; the bottomless gratitude for being allowed back in the fold — is also the NFL’s. Irvin admires Roger Goodell. "People get on him and say things," said Irvin. "But I like Roger because when I sat and talked with him a while back, one of the first things he said [of wayward players] was, ‘Michael, I want to find how we can make the story end well.’"

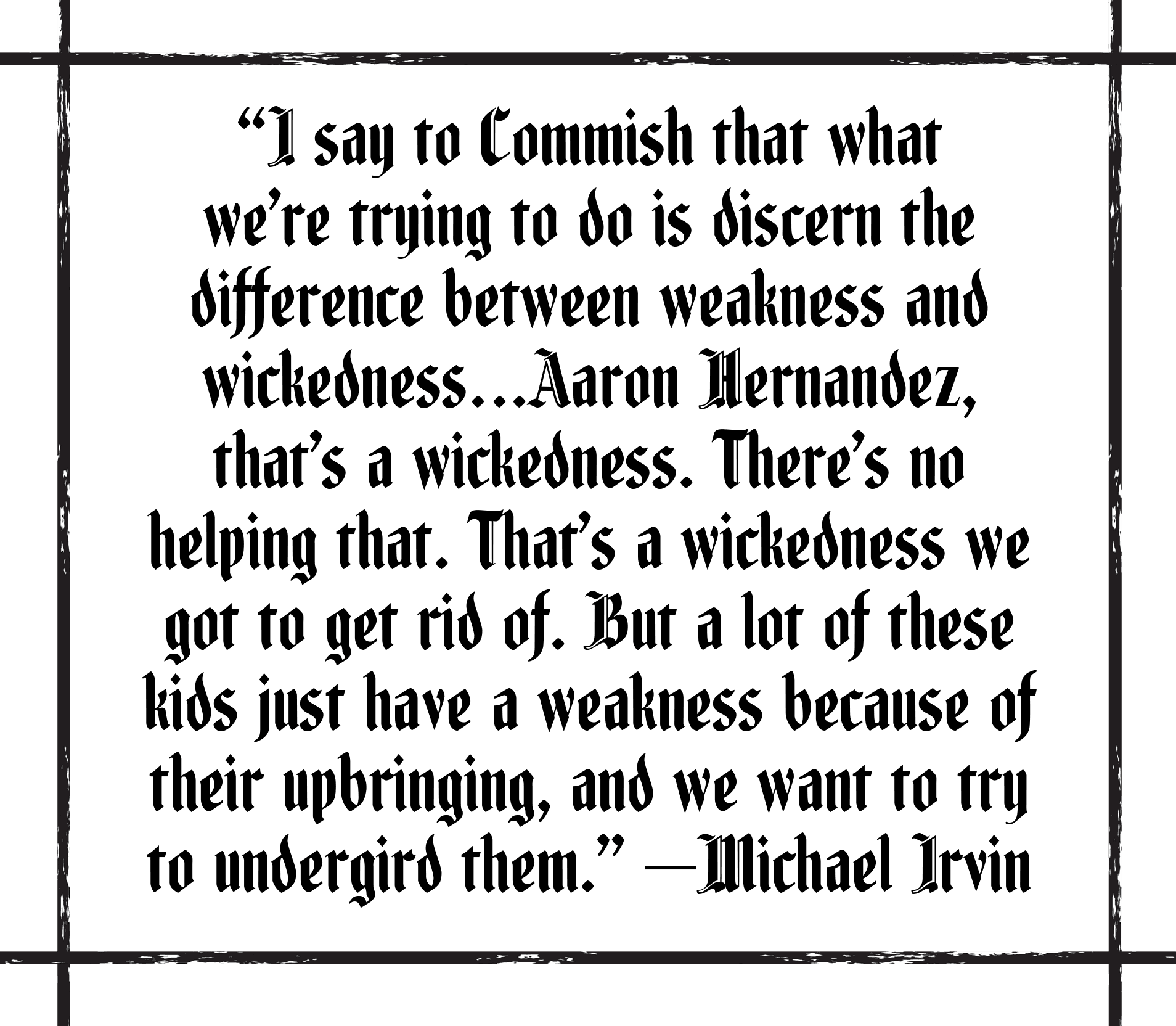

In his occasional chats with Goodell, Irvin urges him to divide law-breaking players into two categories. "I say to Commish that what we’re trying to do is discern the difference between weakness and wickedness …" he said. "Aaron Hernandez, that’s a wickedness. There’s no helping that. That’s a wickedness we got to get rid of. But a lot of these kids just have a weakness because of their upbringing, and we want to try to undergird them."

Of course, it’s the fuzzy line between the wicked and the weak that lies at the heart of the NFL’s thorniest personal-conduct cases. See: Ray Rice or incoming rookie Joe Mixon or possibly even the Cowboys’ own Elliott, who is embroiled in an ongoing investigation by the NFL. Irvin isn’t just using his TV pulpit to sort the players into two piles. He’s insisting that his own sins were ones of "weakness" — the Playmaker is stretching the ball across the line just like he did in Super Bowl XXVII.

As casually as NFL fans once condemned Irvin, now they want to give him a hug. After the halftime show, Irvin exited the field through a tunnel. Fans in Russell Wilson jerseys hung over the chasm and cheered Irvin like he was their own quarterback. Irvin loved them back.

"Hey, Michael!"

"What’s up, buddy? All right now."

"Mr. Irvin. That’s a classic man right there!"

"What’d he say? Heh heh heh. Funny people, man."

As he and Johnson got onto a golf cart that would take them back to the green room, Irvin noticed one final admirer. He was a bald, white man, well past middle age. Seeing Michael Irvin before him, the man held a fist in the air in the style of Tommie Smith and John Carlos.

As the golf cart rolled through the bowels of the stadium, I asked Irvin why he thought everyone had come to love him.

"I got warts," Irvin said. "They make me human."