I.

Last November, Jim Delligatti, the inventor of the McDonald’s Big Mac, died at 98 years old. The owner of several McDonald’s franchises in the Pittsburgh area, Mr. Delligatti debuted the Big Mac in 1967 after workshopping it with the company for about five years. By 1972, it reportedly accounted for 20 percent of the company’s net sales, while in 1973, an otherwise excoriating review of McDonald’s in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette declared it one of the only salvageable items on the menu. The people loved it, and the critics didn’t mind.

John Keim is the manager at the Big Mac Museum Restaurant in North Huntingdon, Pennsylvania, about 40 miles from where Mr. Delligatti first introduced the sandwich, in Uniontown. The museum, which is attached to an otherwise conventional McDonald’s franchise, was opened on the occasion of the Big Mac’s 40th anniversary, and contains, among its memorabilia, a 14-foot-tall statue of a hamburger. My question to Mr. Keim is: Most sandwiches don’t have museums built in their honor. Why are people are so interested in the Big Mac? Keim, who has been with the company for 20 years, describes it as a matter of Newtonian law. "It’s the no. 1 selling sandwich in the world."

Keim’s answer isn’t unlike what Andy Warhol argued when he wrote, "The most beautiful thing in Tokyo is McDonald’s. The most beautiful thing in Stockholm is McDonald’s. The most beautiful thing in Florence is McDonald’s. [Beijing] and Moscow don’t have anything beautiful yet," or what the soon-to-be sitting president meant when he told Anderson Cooper, in praise of fast food, "It’s a certain standard. The one thing about the big franchises: one bad hamburger, you can destroy McDonald’s." These are Chinese finger traps, answers whose proof is that you arrived at them in the first place. Corporate history and Yelp users worldwide would contend otherwise, but the idea stands: McDonald’s is everywhere because McDonald’s is everywhere and anything that’s everywhere must be there for a pretty good reason. Warhol, incidentally, was writing in the mid-1970s. Now Beijing and Moscow are beautiful, too.

II.

A couple of months before Mr. Delligatti’s death, McDonald’s announced the upcoming retirement of its U.S. president, Mike Andres. Andres, who had been with McDonald’s since the 1980s, was credited among other things for the introduction of all-day breakfast, which defibrillated business after years of slumping sales and low guest counts, which is how McDonald’s refers to people.

Though the breakfast menu has since expanded, Andres wasn’t posing radical innovation so much as rallying his base. In 2014, McDonald’s then-CEO Don Thompson said that the company’s core menu — which includes the Big Mac, french fries, and the Egg McMuffin — still accounted for 40 percent of the company’s sales. Many of these items have been around for decades. Though the logistics of implementing Andres’s breakfast program were complex, the foundation remains satire: Let’s do what already works, but better, and more.

Not that radical innovation would ever be the answer for a company like McDonald’s, which, despite its hugeness and uniformity, continues to fashion itself as America’s surrogate living room. As early as the late 1960s, a psychologist named Louis Cheskin stressed the connection between the Golden Arches and mother’s bosom, furthering in the customer’s mind an image of the restaurant as a place of nourishment, stability, and comfort — not just a fact of civilization, but of life. This is why the company calls them guests: At McDonald’s, you are home.

This is more literal for some than others. For the past few weeks, I’ve been taking my breakfast at a franchise near my house, usually before dawn. The drive-through traffic is steady, and some people walk in to take out, but most of the clientele doesn’t seem to have anywhere else to go. They are there with bouquets of plastic bags, mountain bikes piled with collections of recyclable bottles and cans, blankets and backpacks, nursing coffee, waiting out the night. This is not the McDonald’s where teams go to celebrate the game or where grandparents bond with children, but a McDonald’s descended from Edward Hopper paintings, lonely and a little sad but girded by silent strength; a place for people who have time to kill, killing time.

Last summer, a photographer named Chris Arnade put together a compelling if sentimental piece for The Guardian recasting the restaurant as a kind of modern community center where — in places often stripped of better options, at least insofar as Arnade argues — people come together to do uplifting things like study the Bible or find friendship late in life. Last year, a McDonald’s franchise owner in Milwaukee was vilified for limiting a local breakfast club to a half-hour stay, while in 2014 the general manager in Flushing, Queens, called the police on a group of elderly Korean men and women who had been gathering at the restaurant from dawn until dusk, employing a strategy well known to any teenager who grew up near a diner: splitting one order of fries between a dozen people. At times, the rhythms of McDonald’s resemble something more like a city park or a public library without books than a restaurant run by the fourth-largest employer in the world. Only at a fast-food place could life go so slow.

And yet, the company persists. For organizational purposes, here is an incomplete list of innovations McDonald’s has either discussed or piloted within the past couple of years: screen ordering. Customization kiosks. Table service. Wraps. Fancy coffee. "Artisan" burgers. Caprese sandwiches. In 2016, the company redesigned its packaging, transitioning from a somewhat cluttered, painterly tangle of ingredients to a declarative, text-centric design that taps into the current fetish for both minimalism and for the blocky, colorful look of the 1990s, which, right on time, is back.

McDonald’s restaurants through the years (Getty Images)

Despite the general understanding that about 70 percent of business comes from people who never leave their cars, the cosmetics of the restaurant continue to change, too. More than 10 years ago, franchises started transitioning away from their archetypal Mansard roofs to models that resembled a stone farmhouse crowned by a streak of neon exhaust from a passing spaceship — a look that, like the company itself, continues to make promises to both the past and the future. The interior of my own preferred McDonald’s follows a variation on what the company interiors manual calls the "Allegro" theme, which mixes modernist austerity with an accent wall where clusters of libidinal verbiage — SMELL. EAT. HOT. CRUNCH. — are written sideways in scratchy block letters, like the margin doodlings of a high school notebook.

All this amounts to some corporate confusion. In a May 2015 video address, McDonald’s CEO Steve Easterbrook announced the hiring of former Bacardi CMO Silvia Lagnado and former Obama White House Press Secretary Robert Gibbs with the intention of building a "modern, progressive burger company." The following March, the company filed a trademark for the phrase "The Simpler, the Better." At times the company looks like a friend frantically cycling through outfits before a date only to settle on what they wore that morning.

III.

One of the reasons often given for McDonald’s American slowdown is the rise of more refined alternatives. Chipotle, of which McDonald’s owned a 90 percent stake in 2005 and then divested from a year later, is one. The refreshingly artless Five Guys is another. (In a culture where endless customization is sold as a privilege instead of a burden, I find its menu alone relaxing.) So-called "fast casual" restaurants (like Panera Bread) — an oxymoron whose twin imperatives of relaxation and puritanical efficiency could have been invented only in America — count, too, as does food-truck culture, which shares fast food’s modularity and expediency but has the cultural bonus (should you care) of feeling like the product of human beings. Coastal urbanites will of course wonder why everyone doesn’t just eat at Shake Shack, which is decent, and could in certain conversations even be considered cool, without realizing that Shake Shack operates in only 16 states and D.C., many of which have only one or two locations.

Even higher-end adaptations of low food — gourmet burger bars, Southern-style "kitchens" — essentially take the culinary architecture of McDonald’s — stuff you can eat with your hands — and bring it back to the table, which is probably in a converted warehouse or light-industrial space and paired with a cocktail made using house bitters. None of this is fast food, but it intends to bypass your better judgment and hit the spot.

In each case, these are places that do something like what McDonald’s does, but do it healthier, or more agriculturally sustainably, or, if nothing else, aren’t hamstrung by cultural sigma. In some respects, the most forward-thinking changes the company has made in the past few years were to replace the margarine in Egg McMuffins with real butter and to move toward using only cage-free eggs. These are not sexy commitments, nor will they probably matter to the millions of people for whom McDonald’s in the driver’s seat of a car is the closest thing they have to a lunch break, but they are what people who would currently never think of setting foot in the restaurant might need to know before ever considering it again. This past October, The Wall Street Journal reported on a memo written by a "top McDonald’s franchisee" noting that only one in five so-called millennials had ever tried a Big Mac, and you have to try something only once.

The problem is culture, which remains invisible and increasingly cannot be bought. America is in an age of culpability, or of talking about it: We want individuals to acknowledge their privilege, businesses to acknowledge their political allegiances, politicians to acknowledge their business interests. We want transparency, or at least narratives about it, which a place like McDonald’s — which a few years ago started floating promotional videos about agriculture, sourcing, etc. — has presented only tentatively and to a reasonably suspicious public. Sometimes it seems like all the company would have to do to get its shot back would be to put someone important behind a lectern and apologize for marketing heart disease to children.

Of course, all this presumes that people make a habit out of McDonald’s due to preference, instead of something approaching necessity. The company, which remains the biggest fast-food brand in the world, was born alongside the suburbs and the highway, systems that rupture centrality and localism and consolidate commercial development into places people avoid living unless they have to. Studies by places like the USDA show — and have shown for a while — that fast food thrives in places where there aren’t better options, whether they’re healthier, comparably priced restaurants or places where people can buy food that isn’t shrink-wrapped.

Culturally, there are times when enterprises like McDonald’s can seem neolithic, the remainder of a civilization that until recently chose to do things like smoke indoors, and yet the company retains a primacy so undisputed as to be almost invisible. About eight years ago, an artist and data scientist named Stephen Von Worley figured out that the farthest anyone in the United States could get from a McDonald’s was 107 miles, and that required moral imperative and a mountain bike. One hundred and seven miles. In the West, where I live, this would take a reasonable driver — as in, a driver moving at the speed limit — about an hour and a half, presuming roads. The wealthier among us might think of places like McDonald’s as being on the wane, but these are arrows in the leg of a dragon. Ups and downs, educational initiatives and well-intentioned first ladies aside, the company keeps up.

This past summer, McDonald’s CEO Steve Easterbrook said the company was facing competition from a new dark horse: grocery stores.

IV.

One of the more interesting food-related stories that has unfolded over the past year is about a place called Locol. The restaurant, started by food-truck innovator Roy Choi and the more conventionally pedigreed chef Daniel Patterson, was first opened in Watts, Los Angeles, as a healthier and gastronomically enlightened alternative to the neighborhood’s small handful of other options, which include, of course, McDonald’s.

At Locol, you can get a burger made of both beef and tofu or a noodle bowl hinted with ginger and lime, machaca tacos and aguas frescas, veggie nuggets and chili bowls, all framed with a slangy cheerfulness that when ventured by corporate endeavors scans like the work of a narc out of water. In short, the vibe is good and the food is a little different and everything is still basically under $7.

More significantly, the restaurant has built itself into the community surrounding it: The staff is mostly local, and the starting wage, $13, beats the state minimum by about $3 and the federal by nearly $6. Its most optimistic advocates see Locol not just as a place to get lunch but a means of oxygenating an ecosystem, driving down crime, nurturing opportunity in a place where people often grow up without it — not just a restaurant, but a cause.

At the beginning of January, New York Times restaurant critic Pete Wells reviewed the restaurant’s second branch, in Oakland, California, noting, "The people working at Locol are engaged, and seem glad to be there. If Locol can create environments like this across the country, it would be a major achievement," while also giving it zero stars on account of the food. The dichotomy is one that anyone who has ever gone to see a friend’s band play knows painfully well: You’re proud to be there but still prefer the Beatles.

The review upset people. What remains to be seen is if it matters. Wells’s point — that a culinary revolution is going to need better food — is easy to make when you have other options. Locol’s argument is that many people effectively don’t.

You know what restaurant The New York Times has not reviewed lately? McDonald’s. For that you’ll have to turn to the Grand Forks Herald in Grand Forks, North Dakota, which in early 2015 ran a steady, meditative piece of writing by the columnist Marilyn Hagerty on the area’s four franchises. "If you read The Wall Street Journal or USA Today, you might be worried about the future of McDonald’s," Hagerty writes. "If you zip around greater Grand Forks on a cold January day, the McDonald’s restaurants seem alive and well."

Hagerty avoids questions of legacy and ethics and instead focuses on basics: The food is inexpensive, the atmosphere convivial. This is a place, she writes, for families, young people, citizens on the go. At the McDonald’s near Columbia Mall, she enjoys what she calls her "secret sin, a Big Mac for $4.39. Something I do once every couple of years. But they help to fill up active, working people."

I keep dwelling on this — "they help to fill up active, working people" — because it has the unmistakable density of truth. Here is McDonald’s not as harbinger of bigness, uniformity, and ruthless standardization, but of a regular place for regular people, a dream out of Reagan. Here is McDonald’s as it wants to see itself, and in certain ways, for better and worse, as it is.

V.

This week marks the release of a movie called The Founder, about the man who built McDonald’s into what it is today, Ray Kroc. Kroc didn’t found McDonald’s; that was the McDonald brothers, two hamburger stand operators in San Bernardino, California, whom Kroc met while selling milkshake mixers out of the back of his car and proceeded to systematically dismantle through contract and negotiation. It is an origin story predicated less on the birth of one thing than the death of something else.

Ray Kroc outside one of his franchises (Getty Images) / Kroc in his office at San Diego Stadium (AP Photo)

Kroc is played by Michael Keaton, who continues a strong run of roles (including in Birdman and Spotlight) in which a middle-aged man losing his grip on what little he has takes up the gauntlet of his obsession and emerges victorious. Kroc’s successes don’t humble or mellow him so much as provide divine confirmation that everyone else sucked all along: less a redeemed loser than a sore winner.

The story stops around 1961, a year or two before Ronald McDonald and the courting of young consumers, before wider awareness of the diabetes and obesity epidemics, before the stark revelations of Fast-Food Nation and Super Size Me, before the company had entered its imperial phase. At this point, its worst sins are ambition and a little double-talk. One senses that the movie quarantines itself to the early days because everyone already knows what happened next, as though its closing scene — in which Kroc rehearses a speech about the company’s budding progress — is nothing more than an ellipsis bridging something unfamiliar and something undisputed. Of course, this isn’t true: The more monolithic the company becomes, the more opaque and harder to understand.

Watching the film, I found myself wondering about the stories our culture tells ourselves and what morals those stories offer. The movie’s tone is ambivalent: You come away admiring Kroc’s drive while being glad to have never known him. Here we have the story not of David and Goliath, but of competing Davids, two sets of bootstrapping entrepreneurs whose conflict is dramatized as being more about personal style than the bottom line. Both Kroc and the McDonald brothers want to be successful, but diverge in how and, subtextually, why. One of the movie’s subplots involves a crumbling marriage between Kroc and his first wife, Ethel, played by the indefatigable Laura Dern. Dern lays awake in bed alone at night; Keaton pours himself his whiskey before even telling Dern he’s home. Meanwhile, the McDonald brothers, played by Nick Offerman and John Carroll Lynch, are seen caring for each other when sick, patting each other on the back, shepherding each other’s respective hopes and dreams through the disappointments of reality. The irony of the storytelling is poised but obvious: When Kroc makes his rounds to potential investors preaching the concept of "family," I don’t picture him and Ethel, but the McDonald brothers: They, to me, are success.

Still, America tends to define victory as something quantified rather than felt. Watching The Founder, I couldn’t help but think of Jim Delligatti, who through Ray Kroc’s ideals of quick thinking and perseverance came up with a sandwich so popular it attained synonymy with McDonald’s itself. Talking to the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette on the occasion of the sandwich’s 40th birthday, Mr. Delligatti said that people always assumed the company gave him a big raise or percentage of overall sales to reflect the enormity of his contribution, but all he got was a plaque. The museum and attendant franchise were opened in tribute by his son, Michael, and John Keim tells me that when Mr. Delligatti died, the staff wore black ribbons for a week.

Anyway, it was understood that Mr. Delligatti’s design — two beef patties sandwiched by three buns, cheese, lettuce, pickles, and a special sauce reminiscent of Thousand Island dressing — was itself a variant on a sandwich called the Big Boy, served by a local chain called Eat N’ Park, with which Mr. Delligatti was struggling to compete. This is the great American story: Good ideas remain free; the rest is predation and product positioning.

VI.

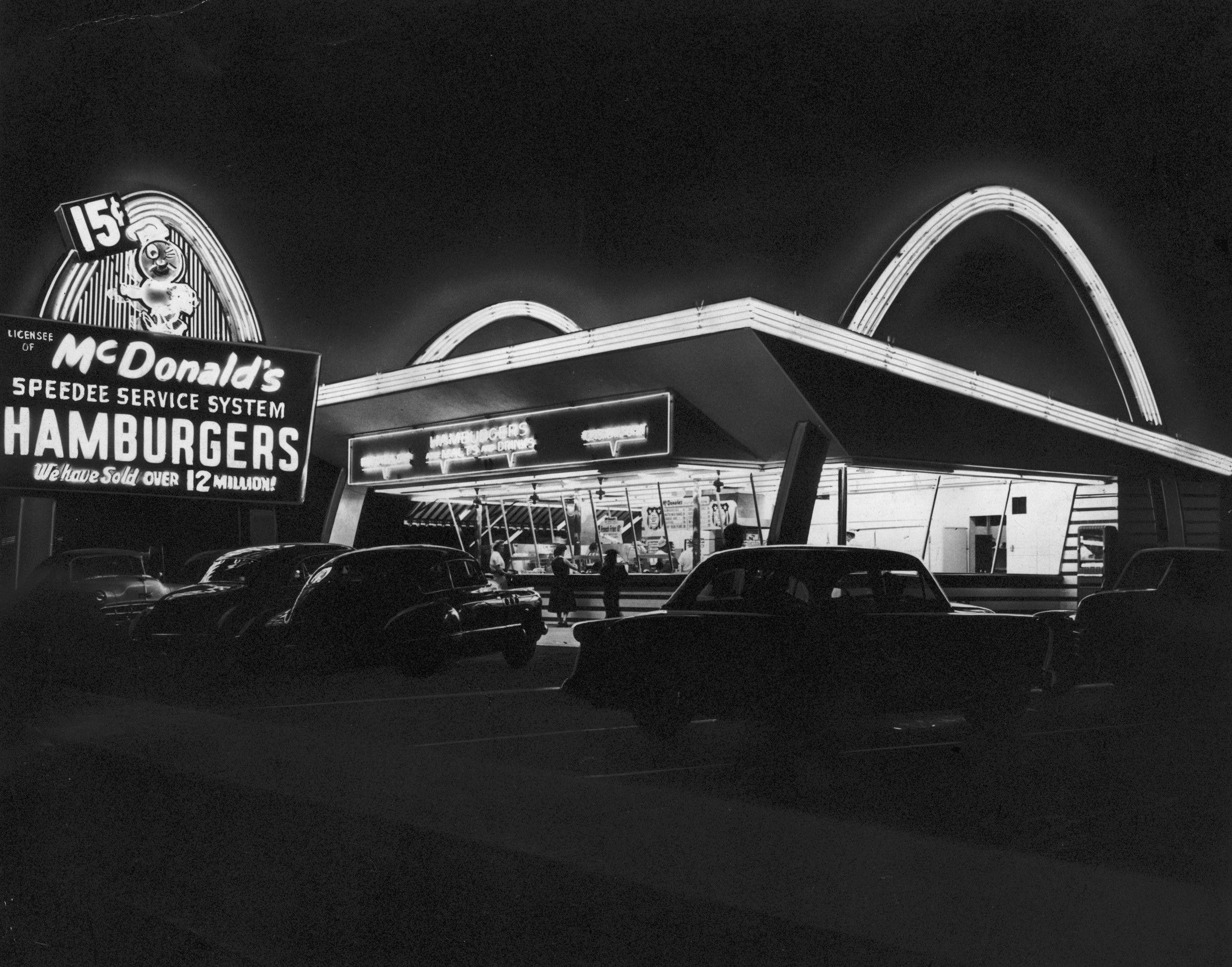

The day after Jim Delligatti’s death, I drove from a friend’s apartment in East Los Angeles down to Downey, a city near the southern end of L.A. County and home to the oldest operating McDonald’s in the United States. A shed-roof structure framed by grand, parabolic arches on two sides, the building appears bittersweetly out of place, a vision of the future according to the past. The National Register of Historic Places tried to add it to its list in 1984, but its then-owner declined; 10 years later it was considered by another preservation trust to be among the most endangered buildings in the country.

Built in 1953, the Downey McDonald’s had been designed with the intention of setting a new architectural standard for the company’s franchisees. Now, it’s the only one of its kind. Linda Dishman, the president and CEO of the Los Angeles Conservancy, remembers a national news team coming out to cover the preservation effort during the mid-1990s. "At first, the story was ‘these crazy Californians, what are they gonna save next?’" she says. "But then people kept coming out with these stories about having gone to McDonald’s like this one as kids." (This is one of the ironies of preservation: Take something nobody cares about and add time.) The only reason the building even survived into the 1990s is because it predated the franchise agreements set out by Ray Kroc. Had the owners kept pace with company preferences, it would look quite different — or it wouldn’t be here at all.

I stepped to the window and ordered two Big Macs and two fries, for me and my friend. I asked the cashier if she knew that the inventor of the Big Mac had died yesterday. She shrugged. I don’t know why I expected the attendants to have been vetted by some higher order, not just cashiers but stewards of the company’s legacy, but I did. I thought she might know the man’s name.

"Yeah," I said. "He was 98."

"Holy shit," she said blandly. The total was $9.83.

We sat and ate in an airy, octagonal pavilion next to the walk-up stand, an echo of the McDonald brothers’ original stand in San Bernardino, which was demolished in 1957, designed to accommodate overflow from the patio. A man in the corner handled his burger with driving gloves. Another drank soda. Posters announcing the theatrical release of Disney’s 101 Dalmatians remake were pinned to the wall, faded from two decades of sun. The burger wasn’t anything I’d make a habit of, and the fries were perfectly crispy but too salty. A group of pigeons on the next table over watched us with intense interest. A woman, nobody I knew, told me to just give the pigeons a fry already. This only encouraged them, but I felt as though I was a visitor and this was their home, and they had as much a right to the fries as I did, if not more.

After lunch, we headed into a small museum tacked onto the back of the pavilion. It was about the size of five or six bathroom stalls. Old advertisements and group pictures commemorating the company’s history were hung on the wall at sloppy angles. Several of the pictures had been removed, leaving two small holes. The wall itself was stainless steel, herald of efficiency and hygiene, of a world without decay, now scratched up with teenage hieroglyphs. After a few minutes of silence, my friend noted that this is one of the only authorized memorials to one of the largest companies on earth. We drove north, digesting, passing a McDonald’s a few blocks away.

A 2007 story in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette on occasion of the Big Mac Museum’s grand opening reported that Jim Delligatti, then 89 years old, still ate them about once a week. Good genes, maybe. As for John Keim, the museum manager, he says he loves the secret sauce and uses it to dip his nuggets, and has been enjoying the new Mac Jr., but has always found the original "too much to sit down and eat all at once." The company could not be reached for comment.