Sportswriting Has Become a Liberal Profession — Here’s How It Happened

Donald Trump’s election was merely an accelerant for a change that was already sweeping across sports journalismBack in the 1930s, you could walk into a press box and find not just a social justice warrior but an actual communist. His name was Lester Rodney, and he wrote sports for the party newspaper, The Daily Worker. Rodney’s politics made his life complicated. Writers at "respectable" outlets like The New York Times would hardly speak to him. But his moral clarity was keener than just about anybody’s.

"I can do a lot of things you guys can’t," Rodney told colleagues, according to his biographer Irwin Silber. "I can belt big advertisers, automobile manufacturers, or tobacco companies. … You guys can’t write anything about the ban against Negro players. I can do that."

Indeed, the segregation of baseball — "The Crime of the Big Leagues!" the Worker called it — was Rodney’s great subject. He was determined to exact justice on the sports page. Rodney pestered owners and managers about their willingness to sign black players and recorded their responses. The pitcher Satchel Paige used Rodney’s column to challenge the winners of the World Series to a game against a Negro Leagues all-star team.

When baseball’s commissioner, Kenesaw Mountain Landis, ignored Rodney’s reporting, Worker headlines taunted him: "Can You Read, Judge Landis?" When Landis refused to give a statement about the progress of integration, they taunted him again: "Can You Talk, Judge Landis?" By the time Jackie Robinson integrated baseball in 1947, black ballplayers knew Rodney’s was one of the first and loudest voices to rally to their cause. But thanks to Rodney’s radioactive politics, he was largely written out of history until his rediscovery a half century later.

Occasionally, Rodney was so committed to being an ideological sportswriter that he tied himself in knots. After a game in the early ’50s, a fan at the Polo Grounds got close to Giants manager Leo Durocher, stole his baseball cap, and made off with the prize. If you’re sticking up for the oppressed masses on deadline, what do you do with that? According to Roger Kahn, Rodney wrote a column arguing ballplayers were workers and should be granted the use of their tools.

Later, police apprehended the thief. He turned out to be a poor Puerto Rican. At the request of his boss, Rodney then wrote the opposite column, arguing the thief was a victim of capitalism and, thus, had as much right to the cap as Durocher. Such were the headaches of being a lefty in the press box.

In 2017, it’d be hard to find a communist covering the Grapefruit League. But it’s easy to find a sportswriter who is infused with Rodney’s passion, his crusading spirit. Today, sportswriting is basically a liberal profession, practiced by liberals who enforce an unapologetically liberal code. As Frank Deford, who joined Sports Illustrated in the ’60s, told me, "You compare that era to this era, no question we are much more liberal than we ever were before."

In the age of liberal sportswriting, the writers are now far more liberal than the readers. "Absolutely I think we’re to the left of most sports fans," said Craig Calcaterra, who writes for HardballTalk. "It’s folly for any of us to think we’re speaking for the common fan."

Of course, labels like "liberal" and "conservative" don’t translate perfectly to sports. Do you have to be liberal to call Roger Goodell a tool? So maybe it’s better to put it like this: There was a time when filling your column with liberal ideas on race, class, gender, and labor policy got you dubbed a "sociologist." These days, such views are more likely to get you a job.

Donald Trump’s election was merely an accelerant for a change that was already sweeping across sportswriting. On issues that divided the big columnists for years, there’s now something like a consensus. NCAA amateurism is rotten. The Washington Redskins nickname is more rotten. LGBT athletes ought to be welcomed rather than shunned. Head injuries are the great scandal of the NFL.

A few decades ago, Taylor Branch’s line that NCAA amateurism had "an unmistakable whiff of the plantation" would have been an eye-rollingly hot take. Now, if you turned in a column comparing college football to the institution of slavery, I suspect few editors would try to talk you out of publishing it. But they might ask you to come up with something more original.

As recently as the turn of the century, you could find columnists hanging Alex Rodriguez’s $252 million contract around his neck. Nobody much writes about free agency like that anymore. Even a bad contract is usually called a misallocation of resources by a team rather than a manifestation of a ballplayer’s overweening greed.

In the new world of liberal sportswriting, athletes who dabble in political activism are covered admiringly. Last year, Slate’s Josh Levin went searching for the voices who were dinging Colin Kaepernick for his national anthem protest. Levin found conservatives like Tomi Lahren and a couple of personalities from FS1. In the old days, such voices would have filled up half the sports columns, easy.

Institutions that made for easy off-day fodder for the writers now get increasing scrutiny. The writer Joe Sheehan has called the Major League Baseball draft "a quasi-criminal enterprise that serves the powerful at the expense of the powerless." Lester Rodney would have been proud of that line.

And these are just issues within sports. Look at the way sportswriters tweet about politics now. "God bless the @nytimes and the @washingtonpost," Peter King tweeted earlier this week after the papers revealed the Trump administration’s web of ties to Russia. Two weeks ago, sportswriters blasted away at Trump’s immigration ban — staging their own pussy-hat protest within the press box. Last year, Roger Angell came out of the bullpen to endorse Hillary Clinton.

"How many sportswriters have you seen on Twitter defending Donald Trump?" asked the baseball writer Rob Neyer. "I haven’t seen one. I’m sure there must have been a few writers out there who did vote for him, but there’s a lot of pressure not to be public about it."

Forget the viability of being a Trump-friendly sportswriter today. Could someone even be a Paul Ryan–friendly sportswriter — knocking out their power rankings while tweeting that Obamacare is a failure and the Iran deal was a giveaway of American sovereignty?

In sportswriting, there was once a social and professional price to pay for being a noisy liberal. Now, there’s at least a social price to pay for being a conservative. Figuring out how the job changed — how we all became the children of Lester Rodney — is one of the most fascinating questions of our age.

There was always a coven of liberals in sportswriting: Shirley Povich, Dan Parker, Sam Lacy, George Kiseda, Robert Lipsyte, Wells Twombly, and the merry band known as the Chipmunks. As Roger Kahn once wrote, "Sports tell anyone who watches intelligently about the times in which we live: about managed news and corporate politics, about race and terror and what the process of aging does to strong men."

But these idealists plied their trade in a media universe almost completely different from our own. The first reason sportswriting became a liberal profession is that the product known as "sportswriting" has been radically altered from what it was 40, 30, even 20 years ago.

The old liberal sportswriter was a prisoner of daily newspapers. If he wanted to write about politics, he had to do it within the confines of a sports story. "You decide whether you think this is a lefty idea or not," said Larry Merchant, who was a columnist at the old (liberal) New York Post. "I wrote a story about a horse that had ridden in the Kentucky Derby. Now, it was in service of the national police in riot control in Washington, D.C. To me, that’s the most natural story in the world!"

Even if a newspaper had a "political" sports columnist, he was nearly always paired with a second, apolitical columnist, who matched the former’s moral crusades with his own rigid attention to balls and strikes.

"When you treat sports as a self-contained universe into which the rest of the universe does not intrude, it will inevitably be conservative," said Craig Calcaterra. You defer to the commissioner, to the head coach, to the reserve clause — to the reigning authority.

The internet leveled the barrier between sportswriting and the rest of the universe. It also dropped the neutrality that was practiced by everyone but a handful of columnists. "We might have been more liberal than you would have imagined we were, but we didn’t bring it in our copy, you know?" said Deford. "We separated our individual lives from what we wrote because that was what was expected."

This loosening of the prose was hastened along by a technological change. Starting in the 1950s, accounts of games ("gamers") became less valuable when fans could watch for themselves on TV. As the game inventory on cable and then DirecTV and then the internet has exploded, gamers are less valuable than ever. Newbie sportswriters have been redeployed. "The people who in an earlier generation would be telling us what they saw are telling us what they think instead," said Josh Levin.

The internet transformed sportswriting in another way: It made a local concern into a national one. On one level, this is pure joy: Now everyone gets to read Andy McCullough. But it also meant that reactionary opinions that may have played in St. Louis or Cincinnati are now held up for ridicule by the writers at Deadspin. I suspect a lot of sportswriters who might be right-leaning either get on the train or don’t write about politics at all.

You might argue, as Neyer does, that the old sportswriters were probably mostly left-of-center types. But without Twitter, it was difficult for anyone to know this. "When I started doing this, in 2003, it felt a little lonely, like I was in a phone booth yelling this stuff," said The Nation’s Dave Zirin. "I didn’t know, or have access to, a community of sportswriters who felt similarly."

The changes in the architecture of sportswriting also changed the profession’s great dilemma. For a century, even sportswriters who had curious minds felt the narcotic pull of the toy department. (It took the carnage of the ’68 Democratic National Convention to shock Red Smith into consciousness.) Then — once woke — the sportswriter faced a second problem: What do I do? Try to sneak politics into my column? Abandon the good salary and Marriott points offered by sportswriting to do "real work" on the front page?

In the Twitter era, I suspect most sportswriters don’t feel this dilemma very keenly or even at all. As the world burns, they turn in their power rankings and then they tweet about Trump.

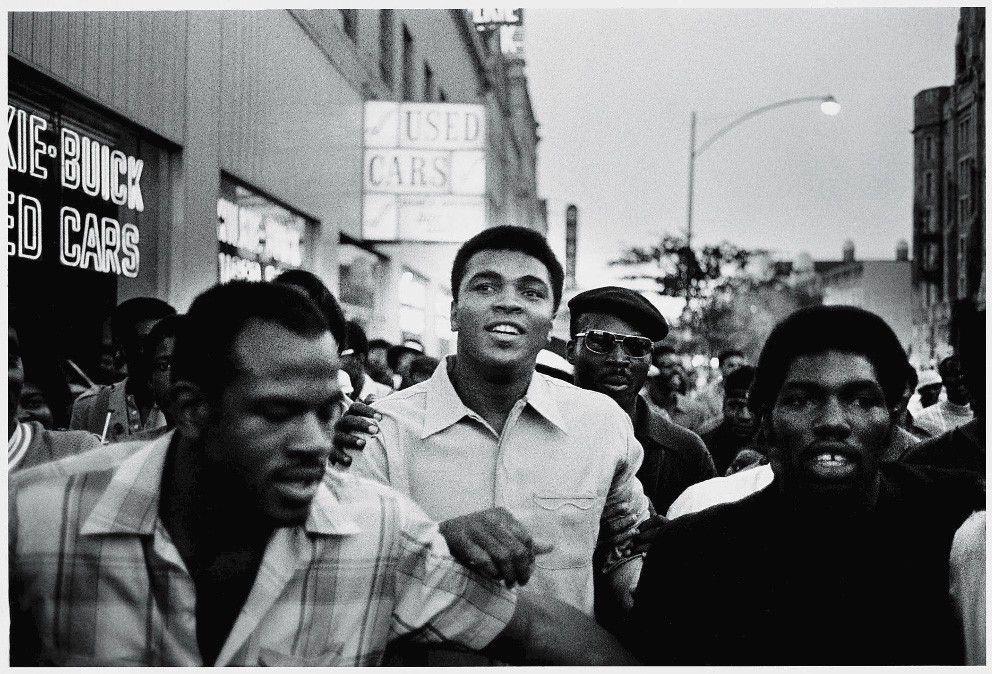

There were other tractor beams that pulled sportswriting to the left. After a slack period since Muhammad Ali and Jim Brown shuffled off the main stage, we’ve finally entered the second great age of athlete activism. "You’re talking about 50 years of pretty much quiet," said Sandy Padwe, who wrote a column for the Philadelphia Inquirer and later became an editor at Sports Illustrated. The new wave of activism "is not like the ’60s by any means," Padwe said. "But it’s a hell of an improvement."

Activism smuggles liberalism into sportswriting — not as opinion but as news. Whatever his politics, the sportswriter must report Gregg Popovich’s lecture on white privilege; Steph Curry calling Trump an "ass"; and a handful of the Super Bowl–winning Patriots refusing to go to Trump’s White House.

It’s not only athlete activism that has rejiggered sportswriting but the athletes’ increased power. In the ’60s, a sportswriter who merely wanted to be a stenographer to the powerful would cozy up to the league commissioner or owner. Now — after the explosion in player salaries and the voice granted by Twitter — the same power seeker is more likely to cozy up to LeBron James, or his agent. As Lester Rodney would tell you, when you’re covering sports from the workers’ point of view instead of management’s, the trade inevitably moves to the left.

Non-sports types like Taylor Branch have given the industry a much-needed noogie. Branch’s 2011 article in The Atlantic transformed the crusade against NCAA amateurism from one often neglected in the sports press into one that burned up the New York Times op-ed page. "It makes sense that a hometown sports page is not going to get into this," Branch said. "Their job is to feed the appetite of the sports fan. This is a fly on their dessert."

Deford told me: "I kill myself when I think that when I ran The National neither I nor the bright people on that paper thought we really ought to examine the NCAA. We never said that. We just accepted that. We took it at face value. We should be ashamed of it."

If liberals have a long-standing delusion, it’s that the presentation of hard data (about everything from climate change to "voter fraud") will win the masses to their cause. But within sportswriting, this is actually true. The publication of college football coaches’ rapidly inflating salaries floated the anti-amateurism crusade. If you know that the NBA signed a $24 billion TV deal with ESPN and Turner, it’s hard to argue that even Timofey Mozgov’s contract is going to bankrupt the league.

"It’s the accumulation of evidence rather than political change," said Bruce Arthur, who writes a column for the Toronto Star. "People just figured it out."

There are chance events too. The fact that Dan Snyder hasn’t put many winning Redskins teams on the field has the side effect of undermining support for the team’s nickname — "If Snyder’s for it," people think, "how can I not be against it?" Similarly, Roger Goodell’s mishandling of issues like Deflategate suggests that he might be mishandling player safety too.

Donald Trump’s election changed sports Twitter into a frisky episode of All In With Chris Hayes. But here, sportswriters are probably being radicalized at roughly the same rate as the rest of the electorate — a process that began during George W. Bush’s administration and continued apace through the Obama years. If most Democrats you know seem feistier than they did 20 years ago, it follows that sportswriters would too.

Talk to the real lefties within sportswriting — Lipsyte, Padwe — and you find they’re skeptical that we’re witnessing a genuine ideological conversion. Sportswriters rarely touch issues like the antitrust exemption and the flag-waving militarism that drenches pro sports. (See Fox’s Super Bowl pregame show for one recent example.) There’s still plenty of PED hysteria, even if it’s getting better. The idea that league drafts unfairly conscript players to teams feels like an issue that’s just starting to get mainstream traction. In 10 years, woke sportswriters will be wondering why our generation didn’t talk more about it.

Maybe what we’re seeing is simply writers plying their trade in a different era. "We shouldn’t piss on things that are progress and are good," Lipsyte said. "But how much of it is really any kind of expression of liberalism? How much is times change and we change with it? Maybe we’re just standing in the same place but being carried along by the flow."

The Obama administration was a dream time for liberal sportswriters, who had a president who talked about sports like they did. Trump’s election caused a convulsion. Lipsyte added, "Kaepernick, the manifestos of Melo and LeBron, and the Trumpish tinge to the Patriots and its reaction from players who say they won’t go to the White House have to be acknowledged, and once you do that, it feels like left-leaning commentary. Unless, of course, it is."

On November 8, we learned a lot of Americans aren’t ready to sail into the progressive horizon. In sportswriting, as in politics, there was a backlash that you could see across the media.

First, conservative political writers began grumbling about their sports pages the way they grumble about the front pages. A 2014 American Spectator column sniffed: "[The sportswriter] now lies prostrate before a new set of masters: Mimosa-sipping Manhattanites and liberal witch hunters whose sole interest in sports is purging football teams of offensive names, obtaining equal screen-time for females, and celebrating sexual diversity." Equal time and diversity — what a crock.

Next, other sportswriters took up the critique. "The sports media is the most far-left contingent of media that exists in this country," Fox Sports’ Clay Travis declared last month. In tsk-tsking the writers — and the athletes they worship — the holdouts sounded like the founders of Fox News. Your media’s been hijacked!

Those who are sitting out the liberal sportswriting renaissance are as likely to tweak the media as they are to offer competing ideas. This week, when Nike released an "Equality" ad starring LeBron James and Serena Williams, Jason Whitlock said: "all this ‘resist, resist’ … it’s bogus. It’s a campaign. … It ain’t got a damn thing to do with you, the ordinary working man."

Earlier this year, when Ronda Rousey was throttled by Amanda Nunes, Travis said: "There were a ton of people in the sports media who wanted Ronda Rousey to be good because it somehow represented their belief that women are better than men." Breitbart approvingly cited the remark.

In a world where liberal sportswriters predominate, there’s a second economic opportunity. You create a "safe space" where sports and politics don’t intermingle, where readers aren’t just excused for not being woke but are rewarded for it. On one of the recent Barstool Rundown TV specials, Dave Portnoy said the immigration protests that were filling airports were "probably the no. 1 story for people [who are] not us … real-world issues that we don’t care at all about."

Then Portnoy cut to footage of a reader — a Stoolie — who’d arrived on a flight from Istanbul while the protests were raging. The Stoolie pretended to be a refugee who’d made it through customs and marched through the terminal, soaking up the applause of the crowd. If there was ever a more backhanded indictment of sports Twitter, I’d love to see it.

What about me? If it hasn’t seeped into the preceding paragraphs, I’m a liberal sportswriter myself. The new world suits me just fine. Would it be nice to have a David Frum or Ross Douthat of sportswriting, making wrongheaded-but-interesting arguments about NCAA amateurism? Sure. As long as nobody believed them.

If anything has gone haywire in this new world, it’s the problem of Leo Durocher’s cap. Writers trying to find the proper, liberal response to new issues wind up tying themselves in knots.

Take the reaction to the Ray Rice video in 2014. There was a hue and cry throughout sportswriting: Something ought to be done! (If there was any criticism, it came from the left: that replays of the elevator video were "re-victimizing" his then-fiancée, Janay.)

Unfortunately, many of the early columns didn’t always say who ought to do something or what it should be. Roger Goodell used the groundswell of rage to suspend Rice indefinitely and increase his already-fearsome power over player discipline.

Such imprecision doesn’t just empower hardliners like Goodell. A few months after Rice’s suspension, Adam Silver, the model of a progressive commissioner, used a gray area in his league’s CBA to levy a harsh punishment against a convicted domestic abuser, Jeffery Taylor. Silver attributed his actions to what he called the "evolving social consensus" — much of which was crafted in the media.

And there’s another liberal ideal at stake here: that criminals who’ve paid their debt to society ought to have a chance to re-enter it. In 2010, Barack Obama congratulated the owner of the Eagles for giving Michael Vick a job after he was released from prison. Rice’s bad acts were very different from Vick’s. But say Rice got another NFL job after his apology tour. Would a sportswriter have written an encomium to the owner who signed Rice? Should they have? It’s an awfully tough question.

I bet old Lester Rodney would have smiled when told the headaches he faced at The Daily Worker are now racking sportswriters from the L.A. Times to SB Nation. For this is what happens when revolutionary ideas become a ruling philosophy — when the former insurgents get the run of the place.