"People are generally not accountable for their actions and full of crap," says Captain Ralph Wilkins, one of the stars of National Geographic Channel’s Wicked Tuna. "What I wanted to do as a young boy was escape." His escape was the ocean. Growing up in Brooklyn, he’d ride his bike for miles until he reached the Rockaways. "Once I started with fishing, it was an obsession," he recalls. He’d spend his summers either on a boat or fishing off a pier. Wilkins doesn’t eat much fish, but he developed a taste for the income it brought him. He started out catching bluefish, striped bass, and flounder — but once he graduated to a bigger boat, tuna became the prize catch.

Because his boats were small and his equipment barely up to the task, some of Wilkins’s battles to reel in giant tuna took four or five hours. "Bluefin is the biggest challenge," Wilkins says. The biggest one he ever caught was 1,050 pounds. He was by himself out on the ocean. "You battle something like that for five hours and it becomes personal," he says. "It’s tug of war with a fish of the sea."

From Moby-Dick to The Old Man and the Sea, fishing is often presented as a romantic, even noble, profession. It requires strength, independence, and a willingness to spend day after day with no land in sight. Over the years, the waves erode the bodies of those who spend their lives on the water. Just to stay upright, muscles must make countless contractions. Wilkins says the ocean has done its best to wear away at his skeleton. "If you look at old men getting off of boats, they’re decrepit." After 30 years as a professional fisherman, he’s trying to slow down — just enough to give his bones a break, but not so much that he has to stop fishing.

Today’s commercial fishing vessels can catch with four employees what used to be the haul of 15 different family operations. The larger boats are nothing like the small skiff on which Hemingway’s Santiago rowed out to sea, but while the industry has consolidated, the ocean still beckons. But if people keep capturing and eating bluefin tuna at current rates, the call could go unanswered.

Today, those who frequent high-end sushi restaurants may know bluefin by names like otoro or chutoro — two sought-after belly cuts so fatty that the tuna’s otherwise dark-red flesh is pink, verging on white. You might have seen articles about absurdly expensive bluefin sold at Tokyo’s famous Tsukiji fish market during the first sale of the new year. In 2017, a 466-pounder went for $632,000 — an astronomical price that was still a deep discount from the record-breaking $1.76 million someone paid for a 489-pound bluefin in 2013.

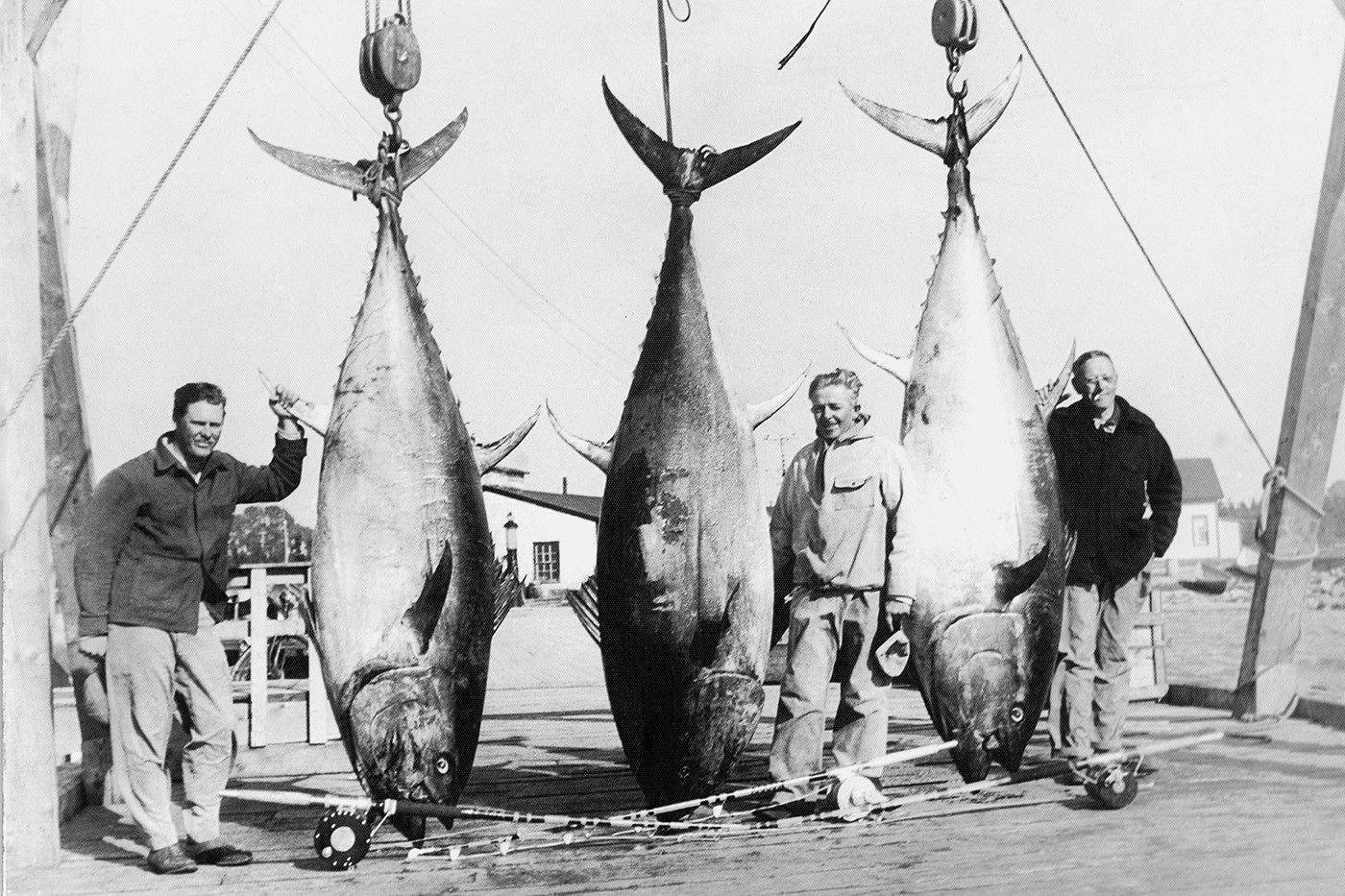

Until the 1970s, bluefin tuna was a literal trash fish. If it wasn’t put into cat food, sport fishermen paid to have it hauled off to dumps (after taking a smiling photo next to their strung-up carcasses). Until the mid-1900s, tuna’s reputation was so bad in Japan that it was referred to as neko-matagi, food too low for even a cat to eat.

Now, bluefin is the most expensive fish in the ocean. The Pacific bluefin population is at less than 3 percent of historic high levels, and last year, a number of environmental groups petitioned the U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service to add the fish to its endangered-species list. Demand is so high that many upscale sushi restaurants have refused to take bluefin tuna off their menus, even amid growing concerns about the precipitously low numbers.

Compared to pandas or floppy-eared elephants, there’s little public sympathy for the declining bluefin. After all, they’re neither snuggly nor puppy-eyed. They’re just fish. Fishermen like Wilkins who are worried about stocks collapsing keep catching the bluefin they can find because if they don’t, someone else probably will. It’s the Catch-22 of catching fish.

Even chefs who serve bluefin don’t know how long they’ll be able to continue. In 2014, Jiro Ono, the subject of the documentary Jiro Dreams of Sushi, told the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan, "I can’t imagine at all that sushi in the future will be made of the same materials we use today."

The world of bluefin tuna, while diminishing, is a lens into the culture and ethics of fishing; it also reflects a nation’s history. Within all this, of course, are two questions: First, how did this fish go from being low-grade cat food to the most expensive fish in the world? And why can’t we stop eating it?

Bluefin’s rise to prominence as the ultimate sushi topping resembles the series of revitalizations that sushi itself went through to become Japan’s most iconic food item. Its first iteration bears little resemblance to the fresh, light morsels on our plates today. Sushi was a way to store food. Fish were salted, covered, or stuffed with rice, and left in a barrel together for a year as the rice fermented into goop. When people were ready to eat the fish, the rice was scraped off and thrown away. Over time, the Japanese developed ways to expedite the process. They applied pressure or put vinegar in the rice to speed fermentation. None of this was a good application for bluefin, which had too high a fat content to preserve well using this method.

As the population of Japan and the new coastal capital of Edo (now Tokyo) rose, there was less of a need to preserve fish and even less time to wait for it to be ready. As Trevor Corson notes in his book The Story of Sushi, restaurants began putting fish fillets on top of vinegared rice and squeezing them in a box for just a few days, then a few hours.

Edo was ravaged by fires. Entire swaths of the city were leveled regularly, and in 1686, Corson writes, "authorities outlawed hot noodle stands during the busy dinner hours." Workers brought in to rebuild the city had little choice but to turn to sushi — a primeval fast food. Out of necessity, Japanese eaters expanded the types of fish they used to make the dish. Finally, Japan started to eat tuna, though more frequently other varieties like yellowfin, dousing it in soy sauce first to mask the taste.

Oddly, it was a love of beef that put bluefin on the dinner table. During the postwar era, American influence helped the Japanese develop a taste for fatty beef. But Japan has little room for cattle ranches and had to import its meat (based on import value, Japan is the largest meat-importing nation in the world), so the Japanese looked for similar flavors in the ocean. Bluefin is the beef of the sea — it’s also the veal. A bite of otoro (toro can be translated as "to melt") is so buttery that teeth hardly seem required.

Like beef, when a piece of bluefin tuna arrives as sashimi, diners give little thought to the giant animal it came from. The largest bluefin ever caught weighed nearly 1,500 pounds and was 13 feet long. A typical adult bluefin is only half that length (and only a third that weight), but is still an impressive sight. In underwater photos or video, divers swimming among a school of tuna are dwarfed by the big fish. But size isn’t what makes bluefin meat so revered. For that, we have the fish’s biodynamics to thank. The bluefin’s particular way of torpedoing through the ocean is responsible for most of the flesh’s nearly spreadable texture. Unlike a typical fish, which undulates using its entire body, this tuna’s power comes from its crescent-shaped tail, which moves back and forth so fast that the human eye might see little more than a blur. (The U.S. Navy even modeled a spy vessel, the Robo-tuna, after the fish’s peculiar swimming mechanics.) Despite having the ability to move at speeds of up to 50 mph, they seem strangely still while moving through the water. The tail is in perpetual motion, but the rest of the body shows little exertion. Less movement in the body, more fat.

Bluefin, like sharks, are passive breathers. Breathing consists of running water over their gills, which is why they have to stay in constant motion — moving at least one body length per second — to get enough oxygen in their blood. They swim across oceans this way. Bluefin sit between the world of fish and the world of mammals. They don’t give birth to live young, but they’re warm-blooded, unlike the majority of fish. If fishermen don’t cool the tuna down after catching them, they can overheat enough to cook themselves. Bluefin aren’t just the kings of fish — they’re a marvel of engineering. Yet it’s not until bluefin have been caught, gutted, and carved into small pieces of sashimi that we recognize their value.

By the time they get to us, they’ve been auctioned, portioned, shipped around the world, and artfully plated. Under restaurant lighting, they’re served as pieces of otoro, chutoro, toro — all cuts of fatty tuna belly — or akami, the redder and least expensive part of the fish. The price of tuna oscillates constantly since most of the supply still comes from the wild; the price for a 400-pound fish can fluctuate from $15,000 to more than $1 million.

According to Sasha Issenberg, author of The Sushi Economy, bluefin tuna might still be swimming merrily along in record numbers if it weren’t for air travel. More specifically, if it weren’t for Japan Airlines (JAL). In the late 1960s, the airline was filling its cargo areas with consumer electronics to be sold to the American public, but on the way back to Japan, the giant planes were empty. An employee named Akira Okazaki was given the job of finding an American product that the Japanese prized enough to merit the higher cost of air travel. After seeing the prices bluefin tuna commanded at Tsukiji, Okazaki realized the giant fish was just what JAL was looking for.

Okazaki’s idea of loading plane cargo areas with bluefin would change the global appetite for fish forever. For the first time, East Coast fishermen could reach the ravenous stomachs and pocketbooks of Japan’s sushi lovers thousands of miles away. August 14, 1972, is known as "the day of the flying fish" among Japanese fish market regulars, Issenberg writes. It’s the day when the first notable auction of bluefin tuna from America’s Atlantic coast sold for $120,000 at Tsukiji. In short time, "flying fish" were being sent from fishermen to eaters all over the world. By 1974, 91 percent of JAL flights from Canada to Tokyo were filled with bluefin tuna. Seasonality was no longer an issue for sushi chefs; suddenly, instead of simply relying on fishing grounds close to home, migratory fish like the bluefin could be obtained as they roamed throughout their oceans-wide territories. The hunt was on. The process of capturing bluefin was expensive, but the rewards kept growing. By the 1990s, Tsukiji was selling Atlantic bluefin for $40 per pound on average. That’s more than $20,000 for an average-size fish.

Fishermen who had once used little more than a boat and intuition to find bluefin soon turned to technology to reel in the diamonds of the ocean. Most boats today use GPS navigation as well as a form of sonar to help spot fish swimming beneath the surface. Bluefin can dive deeper than 3,000 feet, making them hard to locate unless they’re feeding near the surface. As the population declined, an already elusive fish became even more difficult to find. In 1957, a school moving near the coast of Spain was found to occupy 7.2 million cubic meters. The Empire State Building holds only a little more than 1 million cubic meters. Even at stable population levels, it’s unlikely bluefin will reach those numbers again.

A bluefin tuna usually lives from 15 to 30 years. Over just two decades, Issenberg writes, the price Atlantic fishermen could get for bluefin tuna rose 10,000 percent. And in a little more than one tuna generation, the trash fish that turned to gold became endangered.

The faction of top chefs who serve bluefin tuna is like Fight Club. No one talks about bluefin. Of the 20 top sushi restaurants around the world I contacted that serve bluefin tuna, only two offered to speak to me. There were polite responses from a few who were "unable to participate" and a lot of silence from the others.

I ask Kato, a chef at Tojo’s restaurant in Vancouver, Canada, why people eat bluefin. He scoffs at the question. "Basically, it’s very fatty with a nice texture," he says, as though it should be obvious. Bluefin tastes good because it tastes good, and chefs serve it because that’s what belongs on the menu of a top sushi restaurant. Kato explains that the restaurant tries to be "ocean wise" in its choice of bluefin and buys only wild fish versus tunas fattened in Mediterranean fish ranches. Tojo’s worries about where its fish comes from and how it’s caught, and it composts instead of throws food in the garbage. For Tojo’s, and many other restaurants, the act of worrying is enough.

Neal Covington, the "afishiando" for Sushi Nakazawa in New York, says that bluefin tuna is one of the restaurant’s most popular items, yet far from the only type of fish it serves. Skipjack, albacore, bonito, blackfin tuna, bigeye tuna, and others are on the menu.

"With that said, bluefin will reign supreme in the diner’s eyes for its range of different cuts as well as its oil content and texture," he writes in an email. "The buttery, oily, creamy texture puts it at a higher demand and into the coveted spotlight among sushi beginners and connoisseurs alike."

Most of Sushi Nakazawa’s bluefin tuna comes from the East Coast. Occasionally it gets customers who request their omakase menu not include bluefin, "which we gladly accept and we take that chance to show the quality of other tunas we serve and that there are additional options," Covington says.

Though it helps that the East Coast is the nearest source of bluefin for Sushi Nakazawa, Covington says that the restaurant prefers staying domestic, considering the United States’ strict adherence to fishery laws. "Great taste is any restaurant’s goal," Covington writes. "With that said, if what the restaurant is using is disappearing at an alarming rate, they too will disappear at an alarming rate."

Kato takes a more macro view of the bluefin controversy. "If you destroy the planet you’re not going to do any business from that point onward," he says. No planet, no ocean, no tuna. "Think about the countries getting their energy from burning coal and the deforestation of the Amazon," Kato says. "If you talk to Al Gore, he will tell you what’s going to happen." When the entire planet is set up as a straw man, Kato’s point is hard to refute: What good is it to save one fish while we’re still destroying the ocean with pollution and acidification? Tojo’s will continue to serve bluefin to its customers, but it won’t broadcast that fact.

This seems odd. Is a sushi restaurant that serves bluefin under the table any better than an oil company that refuses to talk about climate change?

Tojo’s is not the only one to take this approach. Nearly every high-end sushi restaurant that makes it onto a "best of" list serves some type of bluefin tuna. In the United States, the Iron Chef Masaharu Morimoto has it on his menus, as do Nobu Matsuhisa and Masa Takayama. But when bluefin’s precipitously declining numbers made it into the headlines in 2009, many of these chefs were attacked. A number of celebrities threatened to boycott Nobu after its menu was singled out in the documentary The End of the Line. "It’s astounding lunacy to serve up endangered species for sushi," the actor and writer Stephen Fry tweeted in the midst of the debacle. "There’s no justification for peddling extinction, yet that is exactly what Nobu is doing in restaurants around the world." A member of Greenpeace compared serving bluefin tuna to whipping up a "rhino burger" or "tiger steak." Greenpeace investigators later DNA-tested the fish at Nobu to confirm that it was selling bluefin. Nobu’s sole response was to add an asterisk next to bluefin tuna on the menu, reminding customers that it was "environmentally challenged."

While chefs who have removed bluefin from their menus are outspoken on the subject, those who still slide a plate of delicious otoro to their customers are trying to do so discreetly. Chefs often include it in their omakase tasting menus but don’t mention it on their websites or social media. It’s hard not to interpret the silence as guilt.

Bluefin serves as a bastion of sushi culture and tradition; when a food item has that kind of significance, some chefs are willing to defend unsavory practices in the name of gustatory delight. When California passed a foie gras ban in 2004 (later overturned), chefs throughout the country spoke out in protest. Foie gras, lest anyone forget, commonly involves force-feeding ducks through a process called gavage, which enlarges their liver up to 10 times the normal volume. Chefs compared the rule to Prohibition and others eulogized foie gras’s culinary and cultural importance in French cuisine. Every time the bluefin tuna population drops, environmentally savvy eaters rise up against the practice of serving it. Restaurants won’t defend their actions yet they persevere in the shadows of "chef’s choice" menus. Farm-to-table chefs that make their living off sustainability often feature foie gras on their menus, but won’t serve wild-caught salmon, much less bluefin. In the restaurant world, it’s one thing to entertain a spectre of cruelty in order to enjoy buttery foie gras, another to willfully serve an animal out of existence one sashimi at a time.

In general, Americans look askance at cultures where it’s still acceptable to serve endangered pangolin (the world’s most trafficked mammal), sea turtles, gorillas, or elephants. There are stiff penalties for violating the Endangered Species Act. The trouble is, it’s not good enough for an animal to simply be endangered — it has to be added to the official list, and so far, no governing body has done so. Bluefin just isn’t endangered in the right way.

It’s easy to hide something in an ocean. These giant bodies of water cover 70 percent of the planet and yet, to date, humans have explored only 5 percent of them. There are shipwrecks, treasure, and undiscovered species lurking throughout the water, which ranges from wading level to more than 36,000 feet deep. One of the easiest things to lose in an ocean is a fish — even one as large as a bluefin tuna.

In this age of airplanes and satellites, mapping land animals is not a problem. As species creep closer to extinction, we can count their dwindling numbers with a fair amount of accuracy. Thanks to zoo breeding programs, even a handful of animals may be enough to repopulate a species. This is not the case for fish. We simply can’t find them all. The vastness of the ocean means we will never know exactly how many of a given species occupy the deep sea. Which also means we have no idea where the line between endangered and commercially extinct is.

In 1992, Canada had to close its 500-year-old cod fishing industry because they’d fished cod to the point of near extinction. Even with the moratorium on fishing, it wasn’t until 2006 that the cod fisheries were reopened and at a fraction of their earlier levels. Cod were apex predators, and when they were removed from the ecosystem, other fish stepped in, Game of Thrones–style, and took over. Cod may never be top fish again.

Pacific bluefin stocks are at only 2.6 percent of historic high levels, and no one knows whether 1 percent, 2, or even 2.5 is the magic number that will lead to commercial collapse, according to Jamie Gibbon, officer for global tuna conservation with Pew Charitable Trusts. Modern fishing requires a large investment in boats, technology, and other equipment, says Gibbon, not to mention general debt. "There’s a large incentive to keep fishing even if that fishing is depleting the population," he says.

In wrestling, the term "catch as catch can" refers to a style where just about any hold on an opponent is permitted. But it could easily refer to bluefin tuna fishing. Talking about the migration patterns of the great fish, a paper in the journal Hydrobiologia sounded like it was setting up a middle school math problem: Two giant bluefin met in Ireland, then swam more than 3,000 miles apart, ending up on opposite ends of the Atlantic Ocean. Because tuna migrate so far, multiple countries fish from the same stocks. Bluefin tuna are a shared resource. Unfortunately, different nations aren’t always so good at sharing.

It’s a perfect example of the economic theory known as the "tragedy of the commons." Essentially, there’s too much money to be made to stop one country from fishing for bluefin tuna if every other country is going to continue depleting the stock in their absence. Rather than acting in the common good — for tuna and sushi lovers — nations want to get what they can while they can.

Most bluefin tuna that aren’t wild-caught are ranched in the Mediterranean. Juvenile fish are captured, brought into pens, and fattened. Fish farms are generally created in the name of sustainability (and profit), but bluefin ranches pose one of the biggest threats to the species. "In the Western Pacific, over 95 percent of the fish caught are less than three years old," Gibbon says. They’re scooped up before they’ve had a chance to reproduce or add to the population. The ones who go free are caught by fishing boats a few years down the line. "Bluefin are caught at every stage of their life cycle," Gibbon says.

The world may have developed an appetite for sushi, but Japan still consumes roughly 80 percent of all bluefin. In 1970, before American bluefin found its way to Tokyo, Kindai University in Osaka Prefecture began researching how to breed the giant tuna in captivity. "Bluefin tuna are very delicate fish," says Syunichi Kanke of the university’s Aquaculture Research Institute via email. Their method of breathing means that they need large areas to move in and their skin is sensitive and vulnerable to external damage. Mortality rates are high. Pens have to be at least 32 feet deep and 98 feet in diameter to house bluefin. Even so, young fish, which aren’t as adept at steering, often fatally rammed into the walls of their pens. If self-inflicted wounds weren’t the cause of death, stress-related diseases were.

"Our survival rate has gradually increased," Kanke says. It took them nine years to figure out how to raise juvenile bluefin to maturity and allow them to breed. "Today we raise the juvenile bluefin tuna from eggs, but the survival rate at 1.5 months in our hatchery is still only 3 percent on average."

Even if Kindai University succeeds in increasing the amount of farmed bluefin it can raise, there’s no guarantee the Japanese public will want to buy them. To help with public perception, the university opened a restaurant in Tokyo that serves its farmed bluefin as well as other fish. The restaurant functions a bit like a focus group, allowing researchers to get direct customer feedback on the fish and what Kindai might be able to do to make them continue eating it.

Of course, farmed bluefin has its own environmental issues. Being at the top of the food chain, tuna need to eat lots of other, smaller fish. In a farm system, these lower-food-chain fish still come from the wild. While a natural ecosystem balances out the number of predators and feeder fish, farms and ranches can simply keep drawing from the ocean until small fish become endangered too. Farming bluefin tuna, while a valiant effort, may simply not provide enough benefit to the consumer or the environment to be worth it. But research will continue, because keeping bluefin around is a matter of maintaining a culture as much it is about maintaining ethical ground.

It’s an outlandish idea, but what if people just stopped eating bluefin?

When Ryan Roadhouse, chef and owner of Nodoguro in Portland, Oregon, was a novice sushi chef, bluefin was an integral part of serving Japanese cuisine. "As a chef, it was important to understand it and have a palate for it and be able to identify the varying degrees of quality," Roadhouse says. The owner of the restaurant where he worked would buy it even though the fish frequently cost more than they got from customers. The chef thought it showed the restaurant’s prestige. Last year, when Roadhouse went to visit that chef, whom he considers a mentor, he bragged about how he sold "the most bluefin in the [United States] right now." Roadhouse didn’t know how to respond.

Ten years ago, Roadhouse was interviewed about bluefin tuna for a DiningOut magazine article, and he talked about how beautiful and delicious bluefin was. Looking back on it, he’s a bit embarrassed. Only a year or two later, he stopped using bluefin.

The world of sushi is different today from when Roadhouse started, and the availability of fish has been the biggest catalyst. Rather than holding on to the past, he saw removing unsustainable fish from his menu as a chance for innovation. While Jiro Ono sees a future in which lack of availability forces sushi chefs to change the fish they put on their menus, Roadhouse and others are preemptively changing what "high-end" sushi can look like.

There’s now a whole food movement devoted to "sustainable sushi." In San Francisco, patrons of Tataki restaurant will find one of Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch booklets in front of them, and a menu of only sustainable fish to match. Bamboo Sushi, with multiple locations in Portland, Oregon, and Denver, has gone so far as to put fish back into the ocean by purchasing marine reserves that function as "no-fishing zones" and safe havens for marine life. Miya’s in New Haven, Connecticut, serves foods the world has too much of, devoting a section of its menu to foods made out of invasive species such as carp, lionfish, and catfish.

When Roadhouse met Kazunori Nozawa, the sushi chef of Sugarfish known as the "Sushi Nazi" for the etiquette he required of his guests, Nozawa told him that while many people believe the customers choose the restaurant or chef, the opposite is true. "The chef chooses their guests." For decades, Americans refused to eat raw fish despite Japanese chefs’ attempts to serve it. The chefs persevered. Eventually the guests came.

By refusing to serve bluefin, Roadhouse is inviting a consumer base that is willing to go outside the traditional idea of high-end sushi. If someone really feels that they need bluefin, Roadhouse says, plenty of restaurants in Portland will likely serve it to them. Nodoguro is there for the diners who are ready for something different.