I think it was God who first said, “Thou shalt not lie.” Since then, people have understood that telling the truth is good and important, even though they still lie all the time. I still remember my first big fib: I lied about washing my dad’s car with dirt. I had watched him wash the car, but I hadn’t made the crucial connection that the materials involved were as important as the physical movements. So, there I was rubbing dirt, which I had scooped up from dusty patches of the lawn, on the sideboards and doors and throwing it in clumps over the hood because I couldn’t reach all the way. Soon after, when confronted, I lied and said something like, “Wow, who would do that?” Not very confidently mind you, as I realized that the list of probable suspects for this dirt caper was short. But still. I lied and eventually broke down under heavy questioning. Whatever — I was 17 and I learned my lesson. Anyway, many thousands of years after God warned his creations not to bear false witness, he sent his prophet of truth Rasheed “Sheed” Abdul Wallace to earth. The rest is NBA history.

“It just came into my head during a game,” said Sheed, of the moment the Lord revealed the message to him. “It just so happened I felt as though one ref called a B.S. call on me and so the guy went to the line — it was nothing personal against him — he went to the line and he shot that first one and it went clunk. And it just came out. Ball don’t lie.”

Thus spake the Lord.

Whether or not inanimate objects are capable of divining truth from lie is a question that has dogged human civilizations since almost as long as lying itself. The Old Testament speaks of the casting of lots as a method for knowing the mind of God. The ancient Etruscans practiced haruspicy, which is a means of predicting the future by reading the entrails of animals. And, for years, college-age Americans have entrusted some of their most sensitive life decisions to the sage cyclopedic eye of the Magic 8 Ball. In my personal experience, the 8 Ball was right more often than it was wrong. But, what of basketballs?

The Ball Don’t Lie Commandments, as set down by Sheed, are as follows:

— If a foul call is disputed by the one cast as the guilty party, then the ball will have final say over whether the call was right or wrong. If the shooter misses one or both foul shots, the ball will be said to have told the truth and the call will be registered, in the minds of all that have seen the play, as unjust. It then behooves the wronged party to exclaim, with ferocious energy “Ball don’t lie!”

— The opposite also holds true. If, after a disputed foul call, the shooter hits all of his free throws, then we can say that the referee was indeed correct. Either that or the ball lied.

Which leads us to the essential question: Does the ball not lie? Or does it? I decided to find out, once and for all, using only the most cutting-edge scientific methods.

Since the 2014–15 season, the NBA has been releasing its Last Two Minutes (L2M) reports, which log calls made in game situations when the score is within five points with two minutes left in regulation. These calls are analyzed after the game and categorized as either correct call, incorrect call, correct non-call, or incorrect non-call. I logged every incorrect call then looked at the scoring opportunities that followed to see whether the ball is indeed truthful.

Note: The sample size was relatively small and consisted of only this season’s L2M reports. Some more rigorous analysts might have a problem with this methodology. That’s fine. But we’re on the trail of magic here.

Findings:

Foul shots

Players who benefited from incorrect calls shot 80 percent from the line. Currently, the league-average free throw percentage is 77 percent. Last season, it was 75 percent.

Verdict: This season, the ball lies during free throws.

3-pointers

Players who shot 3-pointers directly after benefiting from an incorrect call have missed all of their attempts so far this season.

Verdict: When it comes to 3-pointers, the ball is 100 percent truthful.

Layups

Players who shot within three feet of the basket after receiving possession due to an incorrect call are shooting 33 percent. League average is 62 percent.

Verdict: With layups, the ball is overwhelmingly truthful.

What does this mean? You get weird outcomes with small samples sizes. That’s one thing. But let’s ignore that for now because it’s not fun. At this point, arguments for and against the ball lying can be made. Eighty percent at the line after bad calls would seem to indicate lying, while players shooting 29 percentage points worse within three feet of the rim strongly suggests that the ball, in fact, don’t lie. Clearly, we need to go deeper.

Working with a larger (but not that much larger) sample, two economists found evidence for a Ball Don’t Lie effect.

Their paper, published in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology in 2009, is called, “The Ball Don’t Lie: How Inequity Aversion Can Undermine Performance.”

Inequity aversion is a field of study in economics and sociology that seeks to quantify how people respond to inequality in an economic setting. The idea is that human beings are hardwired for fairness, and we instinctively recoil from ill-gotten advantages, even when they favor us. In basketball, this would manifest as lower shooting percentages on foul shots awarded due to objectively bad calls.

The paper looked at the shooting accuracy of players awarded fouls shots which came from obviously wrong calls. “We predicted that players would at some level be troubled by their undeserved gain,” they wrote, “and would therefore be significantly less likely to make foul shots that are attempted as a result of such calls.”

After crunching the data, including 77 instances of foul shots resulting from incorrect calls, the writers found that “players do not shoot well in the immediate aftermath of being awarded free throws” unjustly. They shot roughly 20 percent below their average on the first free throw after a bad call, from over 70 percent to just over 50 percent. Ball don’t lie, then, is a function of human guilt.

But what happens when we go to the source: Sheed himself.

Watching the above video raises more questions. Sheed always yells “Ball Don’t Lie!” after the opposing player misses his first foul shot. This raises important issues of causality. Does the ball’s inherent truthfulness inform the miss or the other way around? A closer listen to Wallace’s holy cry further muddies the waters. He was known to frequently yell, “That ball don’t lie.” This raises the possibility that some balls may be more truthful than others. Or, perhaps, the ball veracity is tied personally to Sheed and Sheed only?

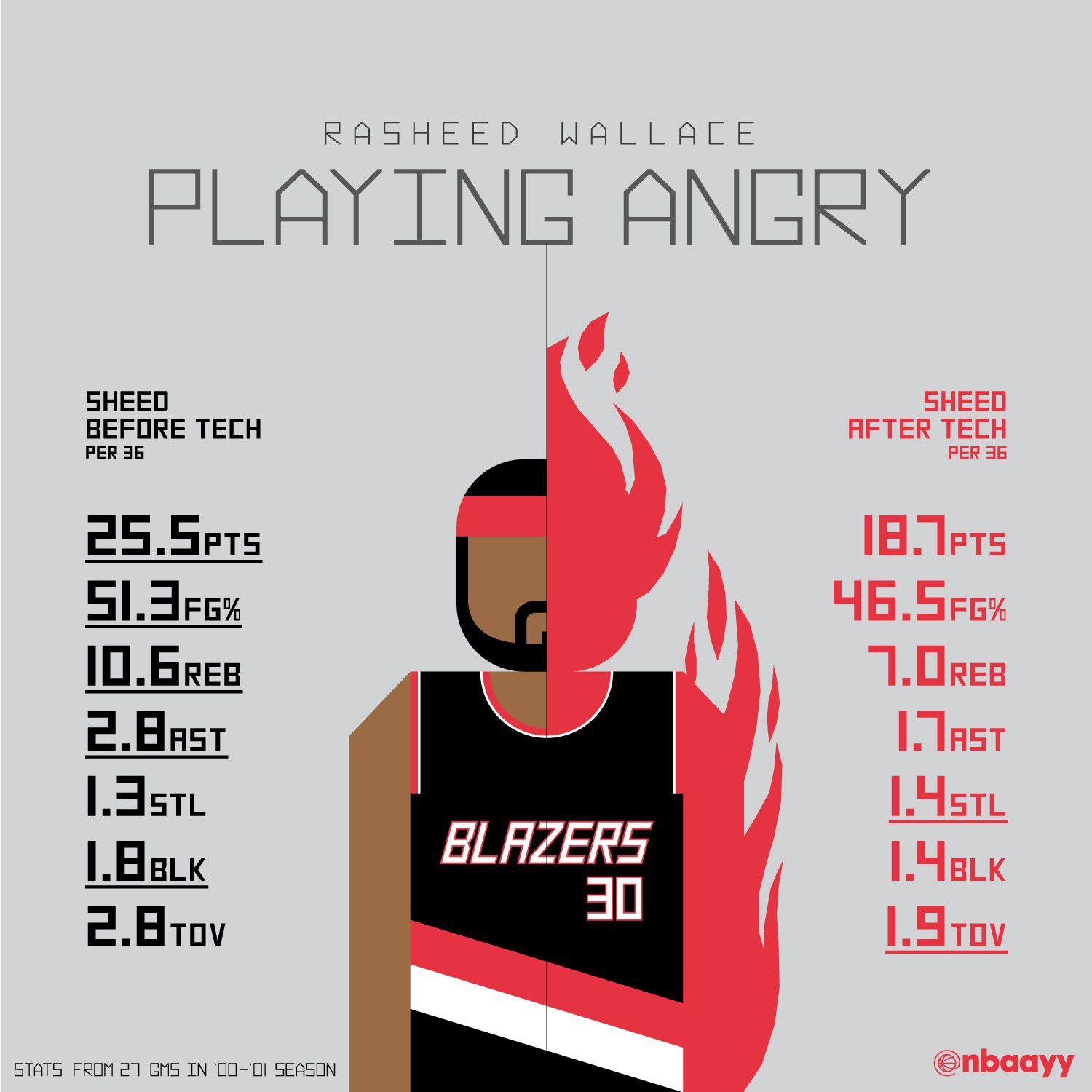

Consider, in 2004–05 Sheed shot significantly worse after receiving a technical foul, 39 percent versus 44 percent for the season. Moreover, in 2001, when Sheed garnered a Mt. Sheed–worthy 41 technical fouls, Wallace shot nearly 5 percent worse from the field after getting T’d up.

Unfortunately it’s hard to come to any conclusion other than that when it came to Sheed, the ball not only lied, but it lied consistently.