‘The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild’ Is a Game Without Gates

Nintendo’s modern recasting of a classic ran the risk of losing what has long set ‘Zelda’ apart. Instead, this satisfying fusion of old-school and new lets gamers go wherever they want in the real world and digital world alike, producing the platonic ideal of a launch title.

I’ve opened thousands of treasure chests while controlling incarnations of Link, The Legend of Zelda’s Hylian hero. The series was born the same year I was, and I discovered it on my sixth or seventh birthday, when I got a gold cartridge gift from a contractor who had a crush on my mom. Since then, I’ve grown from tiny to teenaged to adult, while Link, who was only eight bits when we met, hit polygonal puberty, gained greater resolution, and morphed multiple times from a realistic look to cartoonish shading. Amid all of that evolution, our acquaintance has had its constants. For instance: Ever since A Link to the Past, the early-’90s installment for the Super NES, Link has gotten goodies from chests hidden around his environment and revealed or unlocked through puzzle-solving and combat. And he’s always opened those chests from the front.

The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, the latest addition to the storied series, is, to my knowledge, the first Zelda game that lets Link open chests without facing the front. No longer does the player need to position him perfectly for the game to grant access. Now Link can kick chests open while standing to the side.

I know, I know: It’s not a feature that would send someone sprinting to the nearest Nintendo retailer. It’s a mostly cosmetic quirk that one wouldn’t notice without a Zelda-playing past. In its insignificant way, though, the chest change is Breath of the Wild in microcosm, one of the most minor manifestations of a permissive, tradition-defying design philosophy that produced the platonic ideal of a launch title. Breath of the Wild’s exploratory ethos suits its platform perfectly: It’s a game designed to take the player anywhere, for a system designed to be taken anywhere.

It’s been one week since Nintendo released both that system, the Switch, and its system seller, a Zelda epic originally slated for 2015. The Switch, which can be connected to a TV or, in an unprecedented twist, detached from its dock to play the same games on the go, is Nintendo’s seventh home or hybrid console. Depending on your criteria for inclusion, Breath of the Wild is the 10th non-solely-handheld installment of Zelda (and the 19th entry overall). Almost without exception, its predecessors have been among the best games on their respective platforms, if not their whole hardware generations. A few are inarguably among the best games of all time.

Whenever a new Zelda arrives, then, we hold it to an extremely high standard. Anything less than a classic is a mild disappointment compared with the pantheon: Majora’s Mask and The Wind Waker, A Link to the Past and Ocarina of Time. Yet three decades after Zelda’s debut, we’re also inclined to grade its innovations on a curve.

Zelda, before Breath of the Wild, had long since settled into a nostalgia-generating routine that relied on familiar abilities, animations, and musical cues, and a beloved but oft-repeated progression of challenges. Recent console releases sustained the series’ attention to detail and devious puzzle design but suffered somewhat from a calcified formula in which players reacquired old equipment — bombs, boomerangs, hookshots, and so on — that they then used to access new areas in a specified order, clearing dungeons whose brainteasers and traps were tailored to one item each. Whether out of loyalty to its lineage, lack of incentive to shake up a series that still sold and got great reviews, or fear of tampering with a moneymaker, Nintendo largely stuck to its singular, anachronistic course, delivering quality titles — Twilight Princess, Skyward Sword — that didn’t sully the series’ reputation but didn’t burnish it, either.

Although the 2013 portable title, A Link Between Worlds, grasped the reins a little less tightly, every experiment in Breath of the Wild seems more striking in light of its console precursors’ rigidity. Hence my surprise at seeing Link’s new chest-opening tactic, or, in some cutscenes, hearing actual voice work complementing Nintendo’s traditional presentation of text and short, comedic exclamations. (Some traditions are too sacred to disrupt: Link remains a silent, if facially expressive, protagonist.) But Breath of the Wild doesn’t just look and sound different; it plays dramatically different, by almost any series’ standards. This is a game without gates.

Breath of the Wild constructs its many hours of obstacles out of four foundational abilities: bomb-throwing, time-pausing, water-freezing, and manipulating and levitating magnetic objects. Link adds all four tricks to his holster in the first couple of hours, while sequestered on a protected plateau. After that, he’s free to roam Hyrule with almost zero constraints. Although Link’s armor, health, and stamina can all be augmented, players can tackle quests in virtually any order, secure in the knowledge that any puzzles they stumble upon will be solvable with the same basic skills. In a nod to that open-endedness, the game’s ultimate goal — as usual, rescue the realm, save Princess Zelda, and defeat Ganon — is listed on the quest screen almost from the start, which allows speedrunners to skip straight to the climax.

It might sound as if a game with fewer items and less narrative hand-holding would be easier to program, but the opposite is true: Nintendo had to bake a dish that would last players for days with a recipe that called for few ingredients. Imagine keeping puzzles fresh with only four core components, or designing a sandbox whose every nook and cranny could be equally engaging after five hours or 50, no matter how experienced or powerful the player. That alchemy comes at the cost of a higher difficulty level and learning curve: Link can fall, drown, and come across foes who can kill him with one hit, and swinging swords and shooting bows damages his weapons as well as his enemies. But a forgiving autosave system, paired with the perpetual option to explore somewhere else, eases any concern about being "stuck," a sensation every veteran of the series has experienced in a Water Temple or two.

When death does require a redo, the player’s reflexive frustration gives way to the pure tactile pleasure of traversing the environment. The story’s lack of limits extends to the game’s navigation, which was clear as soon as I switched (sorry) focus from another open-world adventure. To start playing Breath of the Wild, a gigantic game, I had to temporarily stop playing Horizon Zero Dawn, another gigantic game, which came out three days earlier. Despite Horizon’s newness — it’s the first salvo of what strong reviews and early sales figures suggest will soon become a series — the two titles have some core components in common: vast, geologically varied environments scarred from some kind of calamity; day-night cycles and picturesque atmospheric effects; combat that incorporates stealth, a melee system, and ranged attacks; collecting, crafting, and cooking; animals (or animalistic machines) to hunt or tame; and some staples of recent big-budget, open-world games, such as high points that can be climbed to reveal more of the map.

Horizon, a PlayStation exclusive, is in some ways more technologically proficient than Breath of the Wild. Thanks to the PS4’s superior processing power — the Switch’s portability, so freeing for the player, is confining for the developer — it beats Breath of the Wild in the race for graphical fidelity and higher frame rates. But Breath of the Wild feels more like a game from the future, albeit one that retains its ties to an illustrious past.

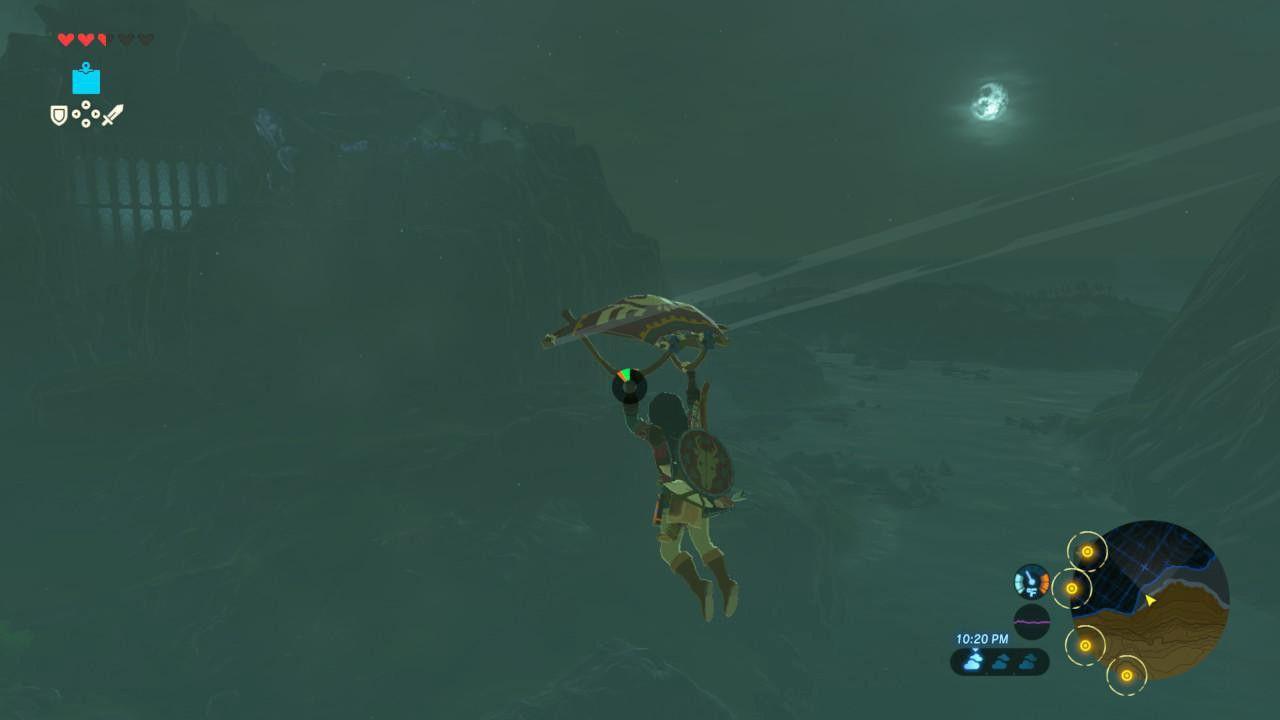

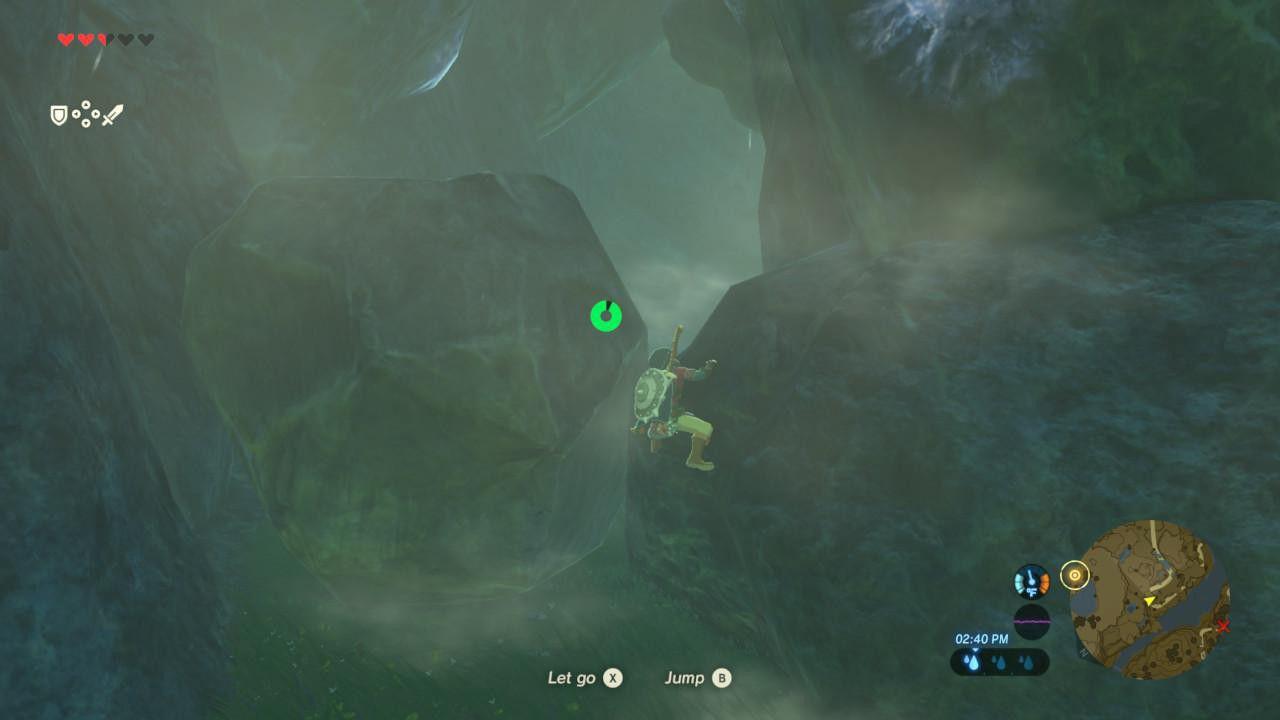

Both games emphasize exploration, but Breath of the Wild strips out every stop sign. In Horizon, cliff faces are barriers, signals to turn around. At best, the player can coerce its protagonist, Aloy, into a halting tumble, using rocky outcroppings to slow her fall enough for her to survive. But in Breath of the Wild, barriers beckon. The more insuperable something appears, the more insistently it seems to say "climb me." Yes, chest-kicking Link can climb, too, the heights he can summit (and paraglide off of) subject only to slipperiness and stamina. Boulders placed in Link’s path no longer impede him, and mountains, towers, and volcanoes in the distance aren’t digital window dressing; they’re potential destinations.

Horizon’s barriers aren’t so intrusive that they puncture the player’s suspension of disbelief. These aren’t the artificial edges of old — the un-budge-able barrel, the indestructible bush, or, most jarring of all, the invisible wall. It makes perfect sense for a steep fall to be fatal. But Breath of the Wild, with its go-anywhere wandering, surrenders some of that realism to create the temptation to try anything.

Nintendo’s new playground is so enormous that sometimes I’ll stare at the map screen and forget that what I’m seeing is a sliver of the world; after zooming in twice on a segment of the map, the close-up still looks like it was taken with a wide-angle lens. Despite the dimensions of the tapestry producer Eiji Aonuma and director Hidemaro Fujibayashi were weaving, though, their team managed to make the space feel full. In case a peak’s mere presence can’t persuade you to scale it, Nintendo offers innumerable reasons to make it to the top: 120 shrines, or mini-dungeons that can be conquered and redeemed for rewards; 900 hidden Korok Seeds, concealed so cleverly that most barely trigger a gamer’s sixth sense; dozens of side quests and comedic encounters; an ecosystem stuffed with flora and fauna that can be catalogued, captured, and cooked to provide tangible climbing or combat benefits (or simply stockpiled in your inventory if, like me, you’re as anxious about virtual cooking as the kind in real life).

Unless you’ve avoided PCs and PlayStations, Breath of the Wild’s textures won’t be the most lifelike you’ve seen, but the artistic appeal of Nintendo’s virtual worlds has never stemmed from their adherence to reality. This one’s sweeping landscapes always offer something to see, ranging from far-off rain showers that leave rocks slick in their wake …

… to sudden double rainbows …

… to some of the most arresting sunsets and sunrises ever to grace a game, which have made me snap stills like a Times Square tourist and remain motionless just to track shadows as they creep across a wall.

Breath of the Wild’s beauty, just stylized enough to hold up as well as The Wind Waker has after almost 15 years, comes across in screenshots. But the gameplay’s subtle brilliance unmasks itself in an accumulation of emergent moments. This is far from the first game to feature climbing, cooking, or a nonlinear narrative; few aspects stand out as unique. But no lone mechanic can account for how well its sum of mechanics meshes, thanks to a governing framework that its developers call a "chemistry engine." Breath of the Wild’s weather and physics — fire, electricity, water — work together in ways that would be predictable if not for the long list of games that have taught us to treat those forces as superficial and noninteractive. That "multiplicative gameplay" — another development-team term — enables several solutions to any scenario, yielding unscripted outcomes that you’ll feel compelled to compare with other players’ and, possibly, to brag about, ideally via YouTube montage.

Breath of the Wild also has its small reminders of the medium’s mundanities. The frame rate sometimes stutters, probably a relic of the game’s origins as a title for the weaker Wii U, the expiring system for which it was also released. Most of the controls aren’t configurable, and some counterintuitive button-mapping leads to Last Guardian–like confusion at inopportune times. The horses are hard to control (not for the first time). Unlike some previous Zelda games, Breath of the Wild doesn’t allow Link to dive underwater, a curious departure from its commitment to mobility. And the story is standard Zelda, another skirmish in the age-old, timeline-breaking battle between an ineradicable evil and the champion who emerges over and over to beat it back.

That boilerplate plot is one place where Zelda’s longevity serves it well, producing different associations in a lifelong player than in someone coming fresh to the franchise. When you’ve been answering summons to seal away Ganon since he looked like this, the first fight feels like a legend, and you really start to empathize with the Hero of Time. If you’ve been avoiding your Zelda debut, though, this couldn’t be a better time to try it (assuming the Switch is in stock). The Legend of Zelda’s previous high points proved that a game’s linearity needn’t be a negative when its architect’s master hand is steady. Breath of the Wild reassures that a nonlinear game — at least one built by Nintendo — needn’t sacrifice the richness and attention to detail that makes linear games great. In giving us so many reasons to go wherever we want, it channels No Man’s Sky’s sense of scale and wonder without the accompanying emptiness, aimlessness, and lack of gratification.

In light of that liberation, it’s appropriate that the experience doesn’t have to stop when you leave the living room. You never have to feel homesick for Hyrule when the world can come with you, perfectly preserved in portable mode. The Switch may have hardware failures, minor design flaws, a lackluster rest of a launch lineup, and question marks when it comes to third-party support, exclusives, and how it will handle anything other than gaming. (Do you even stream, Switch?) But the ability to carry it around like Link’s Sheikah Slate and play Zelda on the way to work, on an airplane tray table, or even in your bed or your bathroom sets the Switch apart from any other system and makes Breath of the Wild an open-world game in more than one way.

Nintendo’s attempt to recast Zelda in a more modern mold could have been an embarrassment, as misguided as Spectre’s bid to Marvel-ize James Bond. In conforming to open-world trends, Zelda ran the risk of losing what sets it apart. Instead, its satisfying fusion of old-school and new reminds us that even when Nintendo borrows ideas from other developers, the company combines them better than anyone else.

An earlier version of this story misspelled the name of the Horizon Zero Dawn protagonist. She is Aloy, not Eloy.