Three seasons ago, the Chicago Cubs won 73 games. In 2015, that number jumped up to 97. And last year, well, you know what happened. In consecutive campaigns, Joe Maddon and Co. made the proverbial leap: from a mediocre team with potential to a bona fide mid-tier contender to a flexible juggernaut that looks set to dominate the sport for years to come. So this week, as part of The Ringer’s 2017 MLB Preview, we’ll be taking a look at what other teams and players — good, bad, and otherwise — are poised for some sudden improvement this season. It’s Make the Leap Week!

On September 28, 2008, 20-year-old rookie Clayton Kershaw came in for an inning of work in relief of Hiroki Kuroda, with the Dodgers leading the Giants by one run. He allowed a leadoff single and a double, then fielded a grounder and got the out at first, leaving runners at second and third. Trying to preserve his team’s slim leads, both on the day and in the division, Kershaw issued an intentional walk to Bengie Molina, hoping to induce a double play. And he did, getting pinch hitter Randy Winn to line out to first, where Molina was characteristically slow getting back to the bag.

Those outs helped Kershaw escape the inning unscathed, ending his last regular-season appearance of 2008 and lowering his ERA on the year — and in his fledgling career — to 4.26. It’s been dropping ever since.

Kershaw’s inexorably falling ERA represents one of the most improbable streaks in sports: The lefty has pitched nine years in the majors and has lowered his career ERA in each of the last eight, even though it’s been minuscule for some time. The gains get smaller, but they keep coming.

Only two other pitchers have had longer streaks immediately following their first seasons: Hal Brown and Justin Speier, who had 9.31 and 8.72 ERAs, respectively, in their abbreviated rookie years. And only 16 have ever lowered their career ERAs in any span of more than eight consecutive years.

One would think that to post a streak this long, a pitcher would have to have a disastrous debut season, giving him an easy ERA target to best for many years thereafter. Or maybe he’d have to break in as a starter and move to the bullpen, where he could throw harder, rely more often on his best pitches, and avoid facing hitters multiple times in the same game. And most pitchers on the list do fit into one of those two categories.

But Kershaw, who hasn’t made a regular-season relief appearance since 2009, didn’t have much room to reduce his ERA. Even his rookie ERA was slightly better than the National League average, and because it came in a partial season, he could put it behind him more quickly. The only pitchers on the list who had lower career ERAs when their streaks started were Hall of Famers Eddie Plank and Hoyt Wilhelm, who qualified in extremely low-offense eras. Moreover, Kershaw has been the best pitcher in baseball for years: He won his first Cy Young Award in 2011 and hasn’t finished out of the top five in any season since. Even so, he keeps beating his baseline. The lower the limbo bar falls, the better he gets at bending beneath.

The projection systems say that this could be the year the streak snaps. Kershaw needs an ERA lower than 2.37 to extend the run to nine years. ZiPS pegs him at 2.29, which would do it, but Steamer says 2.37, and PECOTA has him at 2.45. All told, that’s a toss-up. So let’s break down the reasons why Kershaw could do it while acknowledging the counterpoints that indicate he can’t.

He Doesn’t Have to Be Better

To reach year no. 9, Kershaw has to be better at preventing earned runs than he has been over the course of his career — but he doesn’t have to be better at it than he has been lately.

Kershaw has recorded ERAs well below 2.37 for four consecutive years, posting a 1.88 ERA and a 2.03 FIP in 816 regular-season innings from 2013–16. Admittedly, if baseball’s recent rise in home run rate doesn’t subside, Kershaw could have to contend with a higher-offense environment than he did during much of that time. Despite the substantial increase in scoring in 2016, though, he’s coming off his most spectacular season yet on a per-inning basis, in which he turned in by far his best-ever ERA (1.69) and FIP (1.80). Only two pitchers in baseball’s modern era have ever matched or beaten Kershaw’s park- and league-adjusted FIP from last season in 140 innings or more: Randy Johnson in 1995 and Pedro Martinez in 1999. And no pitcher has ever come close to his 15.6 strikeout-to-walk ratio.

One might wonder why the projections aren’t more optimistic, given Kershaw’s lengthy track record of posting closer-caliber rate stats and the fact that he’s never been less hittable than he was last year. ESPN’s Dan Szymborski, the creator of ZiPS, says there’s a “boring explanation” — regression toward the mean. “He’s got crazy skewed risk at his level,” Szymborski tells me via instant message. “A lot more things that could make him worse than make him better. You’re still going to have regressing, simply because of that almost one-direction risk.”

Granted, no pitcher with at least 500 balls put in play against him during the two-season Statcast era has allowed a lower average exit velocity than Kershaw’s 86.2 mph. If the projections could factor in that weak contact, they might be less skeptical about Kershaw’s ability to maintain his well-below-average BABIP and home-run-per-fly-ball rate.

He’s Still Tinkering

Kershaw, who’s famous for his work ethic, has tweaked his pitch selection, location, and movement more than once since he made the majors, and he’s still searching for ways to improve. Late last season, inspired by try-anything teammate Rich Hill, he started experimenting with a drop-down delivery to take hitters by surprise. Once in a while, he’d lower his arm angle and fire a fastball from about seven inches lower than he typically did. You can clearly see the smaller cluster of lower deliveries on a graph of all of his release points from 2016. (The lone point looking down on the rest was a super-slow curve.)

In real life, Kershaw’s lower angle looked like this:

According to Pitch Info’s park-corrected speed readings from the Baseball Prospectus database, that was the second-fastest pitch Kershaw threw during the 2016 regular reason, traveling 96.5 mph. Contrast that with a traditional fastball from earlier in the same inning, which went only 93.8.

A GIF juxtaposition makes the lower angle even more obvious.

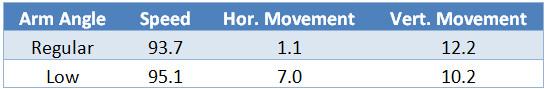

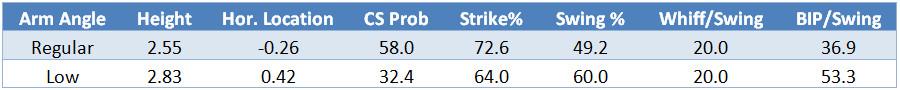

Pitch Info’s classifications say Kershaw threw 25 of the sneaky fastballs, all four-seamers, last September and October. The good news is that they traveled faster and broke farther side to side than his standard heaters.

The bad news is that their results weren’t great.

Kershaw’s low-angle deliveries tended to sail high and outside and have lower called strike probabilities and strike rates than his typical fastballs. Hitters seemed to see them better, too: They swung more often and put a higher percentage of the pitches in play. Only one of those balls in play was hit on the ground.

We can’t say conclusively whether Kershaw’s addition is a dud: Our sample is only 25 pitches, many of them thrown in the playoffs against good teams, and it’s possible that each alternate delivery has some hidden, positive impact on subsequent pitches. That peek at a crafty Kershaw may even bode well for his future, when he has to compensate somehow for slowing stuff. But based on what we’ve seen so far, it doesn’t seem as if the latest Kershaw wrinkle works.

As Jeff Sullivan has suggested, that could be because Kershaw threw exclusively four-seamers from the new angle, whereas Hill mixed in breaking balls too. Whenever Kershaw dropped down, hitters who read the scouting report could count on a fastball, reducing or removing the element of surprise. If practice or further work with Hill helps Kershaw refine his command or mix up his low-angle offerings, the new look could still be a benefit. But remember what Szymborski said: When a player has had a peak like Kershaw’s, any disruption to the routine is more likely to lead to a decline than another new high.

He’s Still on the Dodgers

Kershaw’s surroundings have helped him, not that he’s needed any extra edge. Dodger Stadium is still a pitcher’s park, suppressing offense by about 8 percent last season. The Dodgers stood out on defense, too, tying for third in park-adjusted defensive efficiency and ranking seventh in DRS and UZR. Steamer projects them to finish 12th in UZR this season, although there’s no glaring reason to expect a dramatic drop-off from Andre Ethier and Franklin Gutierrez replacing Howie Kendrick in left, Yasiel Puig playing more innings in right, or Logan Forsythe succeeding Chase Utley at second.

If anything, the Dodgers should benefit from giving more playing time to catcher Yasmani Grandal, who trailed only Buster Posey in framing runs saved last season (despite playing a lot less than Posey did). Kershaw was attached to former catcher A.J. Ellis, whom the Dodgers traded at the waiver deadline; he did better last year when he was pitching to Ellis, recording a 19.0 strikeout-to-walk ratio and a .431 OPS allowed, compared with a 12.8 K:BB and .526 OPS allowed to 41 fewer batters with Grandal behind the plate. But that’s too small a sample to make anything of; the year before that, Kershaw did better when working with Grandal. And in five regular-season starts following the Ellis trade — which made Kershaw cry — his ERA was an even more meager 1.29.

The biggest concern is the back injury that cost Kershaw more than two months last summer. Although he seemed to suffer no ill effects from his herniated disk after taking time off and restoring his arm strength, past injuries are the best predictors of future DL days. Just like last year, of course, Kershaw could keep the streak going without pitching a full season, as long as he does well when he’s on the mound.

Someday, age and infirmity will catch up to Kershaw, who just turned 29. Most pitchers are unpredictable, and time stops all streaks. But in light of his recent trajectory, there’s every reason to think that this year, Kershaw’s can continue.

Thanks to Hans Van Slooten of Baseball-Reference and Jessie Barbour for research assistance.