Nathan Robinson is gesticulating. This is something he does when making a particularly impassioned political argument. On one recent February afternoon, he grabs hold of a cappuccino spoon in a small Harvard Square café and stabs its handle into the air between clenched fingers, the way someone might hold a lit cigarette. His voice raised in a British lilt, Robinson announces, "One of the things alt-right guys are good at is making all these weird, young, disaffected teens feel like they’re the cool ones and the left side is the boring side. We need to have that kind of thing."

Then Robinson becomes expansive, his spoon arm swinging urgently, describing his wish for the new left in the wake of Donald Trump’s presidency. "We are the people you want to be around, we’re the fun people, we’re the cool people, the people who make life better!" he exclaims. I begin to worry about disturbing Café Pamplona’s other patrons, but they seem used to polemics.

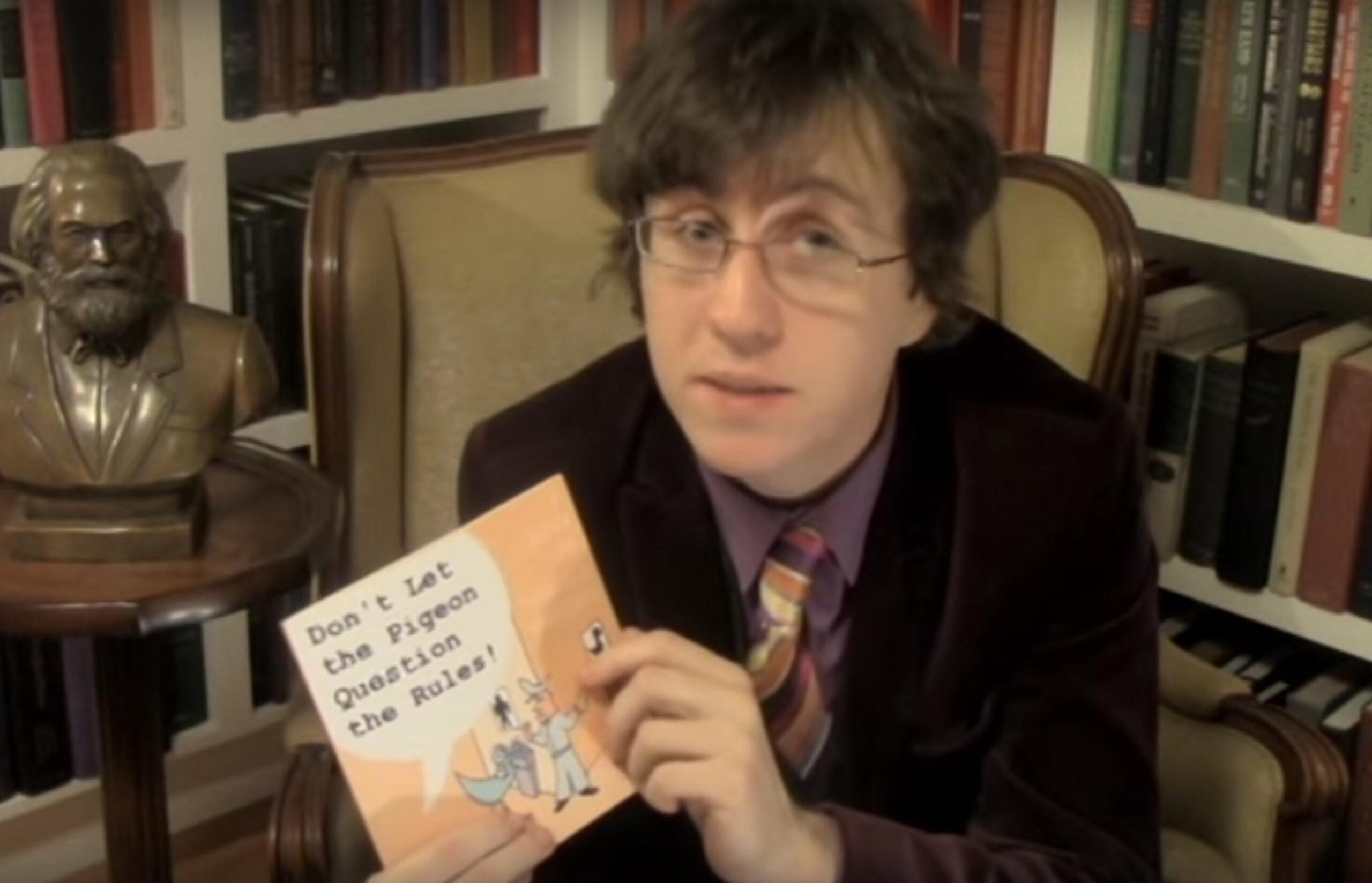

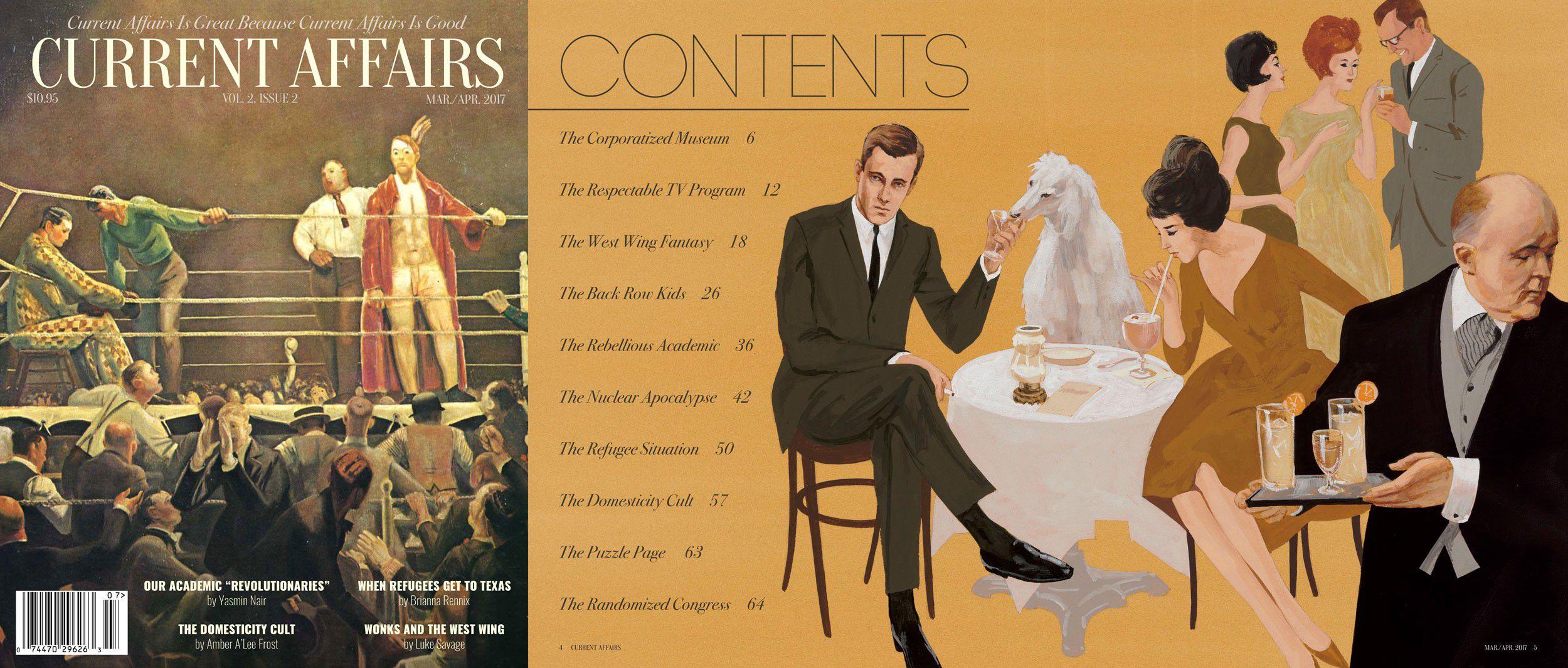

Splayed on the table where we sit are glossy issues of Current Affairs, the left-leaning politics-and-culture magazine that Robinson founded in 2015, where the 27-year-old is the editor-in-chief and more or less the only full-time staffer. Current Affairs is how Robinson spends his free time when he’s not fulfilling his duties as a PhD candidate in Harvard’s sociology department. The magazine’s covers feature cartoonish vintage-seeming illustrations and its logo’s typeface is an august serif that communicates seriousness. "It was intentionally the most boring conceivable name because it’s a name that confirms your credibility," Robinson says. Current Affairs has published only six issues for its now-2,000 subscribers, according to the editor, but Robinson knows what he’s doing. "People haven’t heard of it but they think it’s been around for a hundred years."

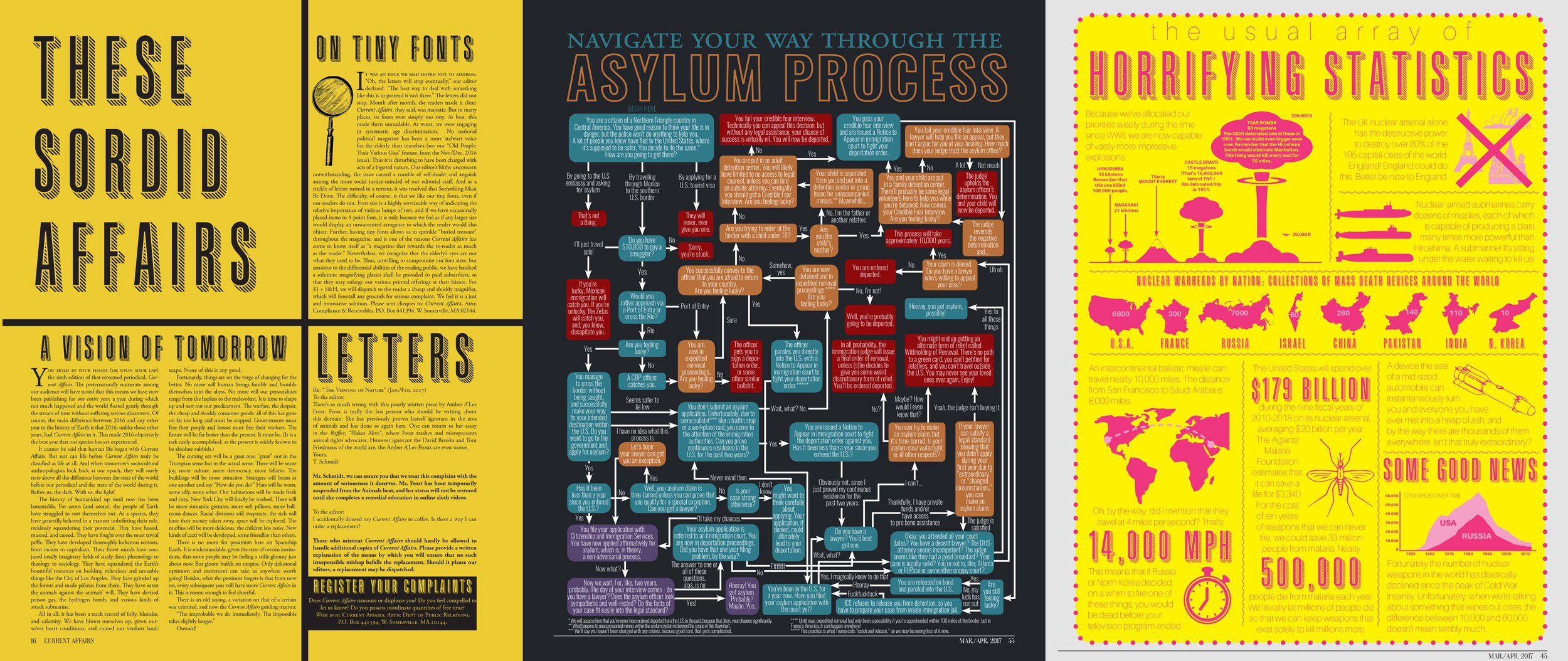

Inside the issues are essays and reviews that relentlessly critique popular entertainment as well as Democratic and Republican politics. No subject is safe from a scathing takedown, from the musical Hamilton to establishment academics and the Democrats’ politesse. Yet the Current Affairs tone is relentlessly sunny and energetic. Its pages are filled with satirical fake ads (think A Prairie Home Companion), comics, and interactive activities that might appear on the back of a highly partisan cereal box. The vibe is more cutesy Highlights than dour New Left Review. "I’m terrified of people getting bored," the editor says with a laugh. "Because I get bored very easily."

Current Affairs is part of a wave of print and digital independent leftist media organizations gaining steam after the November presidential election. Not only are heritage brands like The New York Times and Vanity Fair adding tens of thousands of subscribers; business is also booming for Jacobin, the colorful Marxist journal founded in 2010; Chapo Trap House, a darkly funny roundtable podcast made up of mostly Brooklynite, mostly male 20- and 30-somethings; and The Baffler, a magazine of cultural critique first established in 1988 (and to which I have contributed) that’s the closest predecessor to Robinson’s project. All are helping fill a political vacuum that Hillary Clinton’s loss created, or perhaps revealed to a wider public.

While the likes of The Washington Post and The New York Times charge ahead with investigating Trump’s White House and providing polestars of public opinion for mainstream liberalism, these smaller publications are courting a different kind of follower. Their audiences are still looking for an alternative to the usual media model, a more intimate voice to help them keep up hope during an administration that few expected.

In a recent column for Vanity Fair, the writer James Wolcott lumped many of these types of publications and their writers under the label "alt-left," joining them to the Trumpian alt-right under the banner of their mutual discontent with Obama and Clinton, as well as what he called a desire for a "climactic reckoning." "They’re not kissin’ cousins," Wolcott wrote, "but they caterwaul some of the same tunes in different keys."

The piece provoked controversy, striking a clear nerve among the liberal left. Two articles published at one of Wolcott’s targets, New Republic (where I am also a contributor), symbolized the split. While Sarah Jones argued that the "alt-left" doesn’t exist, as the phrase groups together too diverse a political crowd to be unified by a single label, Clio Chang proposed that such a coalition is necessary for the Democrats to find success in the future.

As Robinson so emphatically points out, the left is in need of some charisma — not to form its own alt-right but to present some kind of meaningful vision that might win elections. The new media brands are tapping into the group of political engagées feeling disenfranchised by plans to Make America Great Again, and in the process of creating their own communities beginning to answer vital questions for the liberal left. Just what does the post-Trump left stand for, if indeed this disparate group sticks together? Will its voice be defined by a grungy podcast, the policy wonks of Vox, the slick Marxism of Jacobin, or Robinson and his band of geeky provocateurs? And what do they have in common, if anything at all?

Robinson’s personal sensibility is what drives Current Affairs. And one thing you should know about the editor and his voice, in a literal sense, is that the British accent is kind of fake. He moved to Sarasota, Florida, from a village outside Cambridge, U.K., when he was 5 years old, in 1995. His father worked at an international corporate training firm and the family decided that they might find a better future in the United States. His parents became citizens in 2001, and Robinson along with them.

"Nathan realized early on that people love listening to a British accent. It gives you this air of authority that Americans seem to like," his mother, Rosemary Robinson, tells me when I reach her on the phone in Florida. "I think he worked very hard to keep it." Amber A’Lee Frost, one of Robinson’s initial writers and now a Current Affairs editor-at-large, freely describes him as "a poor man’s Doctor Who." (He says the accent stems from "a stubborn fear of sounding American that began the moment I first arrived here. It’s far more unconscious than conscious, because I can’t speak in an American accent even if I want to.")

Robinson’s persona is defined by this bookish extravagance. He favors formal clothing, but of the type that Austin Powers might if he were teaching Ivy League liberal arts. At the café, he wears a camel jacket, camel vest, paisley tie, gray suit pants, tasseled leather loafers, and thin-framed glasses, accented by a pinkie ring inscribed with the letter R — possibly from an ancestor, he doesn’t remember. His chestnut hair is in a 1970s wave with a few gray strands. It’s not just style; he’s prone to grandiose statements about Current Affairs, too: "The ambition is to supersede and discredit all other magazines."

He’s joking, but he’s also not — in a meeting at Condé Nast last November, he told Vanity Fair editor Graydon Carter much the same. Carter said that he was impressed with the magazine, especially given that Robinson assembles it in the living room of his apartment. (Carter was unavailable to comment for this story.)

Robinson graduated from Brandeis University in 2011, then attended Yale Law School. He moved to New Orleans to study for the bar, and there met Tyler Rosebush, the future art director of Current Affairs. Dissatisfied with being a lawyer — "it’s dull and I’m bad at it" — he made his way to Harvard, where, between classes, he took up writing and illustrating children’s books, contributing to politics websites, and "getting into YouTube comment fights," as Oren Nimni, his roommate and now Current Affairs legal editor, recalls. Then he decided to make a political magazine.

He taught himself InDesign by writing an entire issue himself, Robinson says. Inspired by the success of Jacobin, which has about 32,000 subscribers, he contacted the older magazine’s printer, web developer, and subscription management provider and signed them on to his new project. In November 2015, Robinson launched a Kickstarter project and raised $16,607 to fund a publication that would "bring a sharp critical eye to the absurdities of modern American life."

Political media is cyclical; particularly on the left, upstart institutions tend to found themselves on the basis of critiquing their predecessors or society at large. Current Affairs is only the latest in a long line of such magazines. The Nation was founded in 1865, edited by a former New York Times correspondent, advocating for civil service reform. New Republic launched in 1914; among its liberal causes was pushing the U.S. into World War I on the side of the Allies.

In the late 1950s, the New Left movement emerged in the U.S. and U.K. as a more mainstream version of Marxist critique, incorporating ideals of civil rights and social justice. Its American proponents included intellectual figures like Noam Chomsky and Howard Zinn. The movement developed its own magazines, too, with the launch of the New Left Review in 1960 and Mother Jones in 1976, named after an Irish American trade union activist. Dissent, a magazine founded in New York City in 1954, and New Republic were also advocates.

Robinson was first politicized at his magnet high school, where a friend urged him to join the school’s progressives club, but his media influences are less about political discourse than vintage science-fiction magazines and The Daily Show. In high school, he also had a half-hour public access TV show that he filmed with friends in the family garage. "It was Monty Python–type skits mixed in with political commentary and satire," his mother explains.

A principal reference point for Current Affairs was Spy, a satirical monthly magazine cofounded by Graydon Carter that ran from 1986 to 1998. Robinson encountered it when the magazine’s archives were uploaded onto Google Books in 2011. "If you ask me if I want to pick up a New Republic from the ’60s and read it, the answer is probably no," Robinson says.

Bhaskar Sunkara, the founder of Jacobin, says he doesn’t mind Robinson’s appropriation of his strategy, though Robinson even copied his magazine’s subscriber email templates, changing only the editor’s name. "Jacobin is in many ways a much more orthodox publication as far as our politics. The backdrop is that we think there’s a political alternative, and that alternative is socialism," Sunkara says over the phone. His magazine is focused on building a coherent socialist movement while "Current Affairs’ solution is a broader tent." He describes Robinson’s position as "broadly anti-neoliberal."

As seen in its initial issues, the Current Affairs approach is about cloaking leftist politics in playful imagery and sharp writing, rather than charts and graphs. Robinson still designs it himself. "I want every page to look different from the other page," he says. "There’s almost no consistency." The accessible presentation and voice "invites people who don’t necessarily agree with the underlying point to read this," he continues. "We have a lot of people who are conservatives read us because we make stuff people like to read."

The magazine’s standout pieces take the form of manifestos, like Robinson’s call for a "Luxury Leftism," a vision of socialism based not on austerity or self-sacrifice but limousines, mansions, and parties for all as equals. He asks, why shouldn’t your politics enable a good time? Amber Frost contributed a key piece called "The Necessity of Political Vulgarity," arguing against Voxian wonky aloofness: "Vulgarity has always been employed in revolutionary rhetoric," she writes. Being mean "is a crucial rhetorical weapon of the politically excluded."

Frost moved to New York City in 2013 to play in a punk band and write music reviews, blogging for the website Dangerous Minds. But she turned to political Twitter and to writing research-driven criticism for Jacobin and other publications, working for the Democratic Socialists of America as secretary for a time. An empty room opened in her Bed-Stuy apartment, and Felix Biederman, who went on to cofound Chapo Trap House, moved in. Frost became a regular podcast guest. In a tweet, she coined the moniker "Dirtbag Left" to describe her crew, a piquant alternative to James Wolcott’s.

After 2008, with the political activation of Occupy, leftist media became reinvigorated. The iconic midcentury publications had survived, and they suddenly saw interest from a new generation, predecessors of figures like Frost and Robinson. "It came from the politics of the economic crash experience coupled with new social movements emerging in the wake of young people realizing the system was built to their disadvantage, experiencing precariousness," says David Marcus, the co-editor of Dissent from 2014 to 2016 and now literary editor of The Nation. "There’s a need for ideas to fill the void or answer the questions raised by the inadequacies of Democratic Party liberalism."

Social media has also made it easier for far-flung converts to access newer voices and publications than the older ones. As opposed to intellectual institutions like The New York Review of Books, whose cofounder Robert Silvers just died, the new generation often comes from outside the literary establishment. These days, a viral tweet can play better than a lengthy book review. "Twitter is this great socializer," says Marcus. Sunkara puts it this way: "If you’re a young person getting politicized now, there’s a bigger chance of you getting into Jacobin than the New Republic."

I meet Frost in a Cuban restaurant near the Chapo house to discuss the left’s ennui and the need for messier politics. Dressed in a faded band T-shirt and jeans, having just strolled in from a recording session, she doesn’t look like a pundit on the job. But that’s part of the point. "In publishing circles, everything’s very genteel. We now have a right wing that’s completely dispensed with the idea of being genteel. These alt-right people have abandoned traditionally conservative ideas and etiquette — they are no longer a necessary part of the conservative identity. It’s significant," she says. "We’re not going to win this by adhering to good manners. Once they stop caring about having good manners, what are we going to say? ‘You have bad manners’? Yeah, we do, fuck you! You can’t clutch your pearls. You have to scare them. You have to be meaner and grosser than they are."

Chapo Trap House embodies that ethos. A resolutely lo-fi effort amid a boom of higher-budget podcasts, Chapo debuted in March 2016. A skit or scripted dialogue usually opens the show, with the core trio of hosts — Will Menaker, Matt Christman, and Biederman — lampooning figures in the news, sometimes by role-playing them. The podcast has evolved its own universe of guest commentators and in-jokes, inspiring rabid devotion from fans who see their own politics reflected in its spirit.

"I think liberalism as a culture produced a very intense snobbishness that people picked up on and they resented. You can’t work with or on behalf of people that you have contempt for," Frost continues. Hence the lowbrow sensibility, raunchy humor, and punk DIY spirit of many of these outlets — they’re imparting a feeling that their podcasters and writers are on your side in your bleakest moments rather than attempting to convince you by logic of a political inevitability. It presents an emotional appeal: "That’s why Chapo has more fans than Jacobin," Frost says. The podcast has more than 11,000 subscribers for its paywalled episodes, netting more than $51,000 a month on the crowdfunding platform Patreon.

Current Affairs splits the difference in tone, creating a community for liberal readers while avoiding alienating those who might not agree with their entire program. The publication’s voice is a specific blend of knowing humor and wide-eyed enthusiasm, never one to back down from a debate. Robinson drives a particularly pugnacious group of commentators united less by creed than tone. "It’s not like they’ve decided on a new set of rules," says Angela Nagle, a scholar of internet culture and Current Affairs contributor living in Dublin, over the phone. "It’s not like a political party or something; it’s more a dissident spirit, a sense that the way to give some kind of vibrancy and life to the movement is to allow a greater range of points of view."

The approach is paying off. Current Affairs brings in around $15,000 monthly, according to Robinson, mostly from subscriptions and direct magazine sales as well as sales of paperback books that Robinson writes himself and publishes under a Current Affairs label. The first, on Bill Clinton, is called Superpredator: Bill Clinton’s Use & Abuse of Black America; a second, on the rise of Trump, is named Trump: Anatomy of a Monstrosity. Purchases of the $60 annual subscriptions (for six issues) have been rising during the new presidency, with an additional handful coming in every day. (Sunkara notes Jacobin gains around 75 subscribers daily.)

Yet the magazine remains a small-scale passion project. And, at times, an inside joke. At the Harvard Square café, Robinson shows me the trolling letters he mailed the likes of Jonathan Franzen and Chris Hughes (the Facebook cofounder who bought and then recently sold New Republic) courtesy of Current Affairs, copies of which are printed as spreads in the magazine. These are mailed as pranks: Robinson offered to buy New Republic from Hughes to save it from further embarrassment. No correspondence was returned, however. The magazine’s elaborate masthead is a bit of a put-on, too. Current Affairs "publisher and chairperson" S. Chapin Domino? "Fictional," Robinson says.

The new wave of leftist media voices could be separated into three categories. There are the hardcore socialists, who use their platforms to promote a holistic political agenda — publications like Jacobin and Dissent. Then there’s the so-called Dirtbag Left, ranging from Chapo Trap House to voicey pop-leftist magazines including Current Affairs and The Baffler. Finally, there are the liberal centrists who want everyone to rally: Vox and Crooked Media, a company that emerged in early 2017 from Keepin’ It 1600 — the political podcast by former Obama staffers (produced by The Ringer) — and which now publishes the podcast Pod Save America, among others.

Under Trump, presenting a different type of political program is important, but the more urgent cause seems to be simply activating the left while surviving to publish again tomorrow. The publications are less about muckraking journalism (so far) and more focused on leveraging commentary, humor, and anger into the self-confidence needed to take on the administration and move past the Democratic Party’s identity crisis for good.

According to David Marcus, the new wave of media institutions both on the right and on the left are "helping reveal a base that was already there," he says. And discourse slowly becomes policy. "I do think that the analysis that has been put forth by left magazines is becoming assimilated by the Democratic Party," Marcus continues. Despite the right’s proclivity to turn pundits and talk-show hosts into office-holders or White House czars, however, "I don’t think you’re going to see an editor at Jacobin becoming a chief of staff for Bernie Sanders, even."

I meet Noah McCormack, the publisher of The Baffler since 2015, in a Flatiron District Italian restaurant with an atmosphere of glossy blandness conducive to business meetings. McCormack’s family is something of a magnate in the independent print world; his father, Win, is the publisher and editor-in-chief of the Oregon-based literary magazine Tin House, and he purchased New Republic from Chris Hughes in 2016, becoming its editor-in-chief. (The McCormacks’ ancestral wealth comes via Illinois Tool Works and Northern Trust bank.)

The Baffler recently underwent a refresh courtesy of the high-end design firm Pentagram; where before it was rather sprawling, now it is sleek and angular. "We live in an anti-intellectual age in general," Noah McCormack says. "The marketplace of ideas has been completely conflated with the marketplace, so left-of-center and left-wing ideas just don’t have much purchase. They have to be artificially subsidized" — usually by wealthy patrons willing to take the hit or foundational trusts. Leftist publications, he says, are "providing a space for the ideas to happen. The larger the ecosystem is, the better for everyone."

Each editor and writer I speak to seems to seek a greater unity, including the founders of Crooked Media, the most centrist-liberal of the bunch and perhaps also the most corporate — unique among the crop, it makes its money from advertising. Cofounder Jon Favreau, who was director of speechwriting under Obama (and a former Ringer contributor), says: "Any voice on the left that’s going to be participating in and interested in making sure Trump isn’t president for eight years and we win back the House is a good voice to hear."

Chapo Trap House, the least traditional operation of them all, gives itself a specific and yet equally universal mission in its twice-weekly episodes: to entertain. "Our responsibility is just to keep doing what we’re doing, to keep making things that make the worst aspects of where we’re at feel bearable," says cofounder Felix Biederman. Humor soothes the pain of being the opposition, particularly when the jokes target subjects like the conservative Times commentator Ross Douthat and build recurring bits off of the much-touted "deep state." Activist or not, "We can give you a voice in the background that you can laugh at things with and there’s something to look forward to."

The aggressive partisanship, ironically, has something in common with the alt-right after all, at least according to its proponents. "They’ve actually taken the Andrew Breitbart view of journalism, which is that we ought to be open about our biases. I appreciate that, and I learn from it," says Ben Shapiro, an acolyte of Breitbart and the founder of The Daily Wire, a bombastic conservative website. "I think that everyone is rushing to the new media as an alternative to the restricted distribution mechanisms of the old media, and that’s great. I enjoy listening to a lot of those [leftist] podcasts."

If the new left media shares core values, it might be these: Trump is bad. A fair democracy is good. The rampant concentration of wealth is bad. Open borders are good. Diversity is good, too. All are welcome — the tent is getting bigger. Whether you call them the opposition, the #resistance, or the alt-left, they are becoming a coalition and a self-sustaining ecosystem.

The more that establishment figures like Wolcott try to take them down, the more coherent they appear.

"The way that critics of the movement write about it can shape the movement itself," says the Current Affairs contributor Angela Nagle. "If you’re attacked with other people, you’re more likely to bind together with them."

At Harvard one morning a few days later, Nathan Robinson is standing before one of the sociology class sections that he teaches to undergraduates. He’s wearing a purple velvet jacket, lilac shirt, and paisley tie under a white vest, the very picture of a liberal arts education. He dances energetically at the front of the room, evincing more enthusiasm than the students, who shift restlessly in their activewear along the horseshoe of tabletop.

Robinson leads a discussion of cults and the ways in which they use rituals to create a sense of belonging. Might the ceremonies of a college sports team be reminiscent of a cult? An innovation of which he is proud are triangular nameplates for the students that can be flipped to red, yellow, and green sides based on how amenable they are to adding to the conversation. One young woman, flipped to green, describes her experiences at Burning Man as cultlike.

After class, Robinson and I go to the café in the atrium of Harvard’s Fogg Museum, which was designed to resemble an ancient Roman courtyard. The sunlight falling through glass onto weathered stone arcades is redolent of the failed grandeur of democracy and the ruins of civilizations. Robinson orders another cappuccino with a small circle of quiche, and I have a grainy matcha latte.

I bring up James Wolcott’s article, which Robinson and his roommate Oren Nimni had discussed that morning. Is there such a thing as the alt-left?

"There is a left that’s critical of the left just like there’s a right that’s critical of the right, but it’s misleading to categorize it that way. The people on the alt-right really are pretty monstrous. Freddie deBoer is not Richard Spencer," Robinson says, referring to a popular leftist blogger and academic. "The key thing about the alt-right is that they’re Nazis, not that they criticize Hillary Clinton."

"Is there a coherent movement and do we all sit in a room and plot? Obviously not. There are a few new writers, I think, and types of voices in the media who share some common themes."

In May, Robinson plans to take some time off from Harvard and move back to New Orleans, where he might work on his dissertation, but will likely double down on Current Affairs, renting office space and creating an actual editorial calendar. Professionalism is part of the agenda.

"What I think about a lot is how to make left ideas mainstream and not fringe. If you want to be a serious and credible thing, the first thing is to adopt the aesthetic of serious and credible things. I’m going to wear a tie. That’s a cheap way of buying credibility," he says, that British accent more precise when he’s making a pronouncement. "It’s entirely about being useful. I don’t really want to produce just entertainment."

Some of the goals for Current Affairs are more prosaic, however. "I do like a magazine that, when you pick it up, things fall out of it. I want things to fall out of our magazine someday. You pick up The New Yorker, all sorts of shit falls out. You can’t keep it in," Robinson says. "I dream of a big fold-out map or a pop-up. People just need to subscribe, and we’ll do incredible things."