Not long after every senior member of The Good Fight’s central law firm is subpoenaed by the Department of Justice, third-year associate Lucca Quinn (Cush Jumbo) reluctantly offers the team an unexpected Hail Mary: the so-called race card.

“I’m not sure if this helps,” she says hesitantly. “But Kresteva’s boss, the assistant attorney general, was concerned that the investigation was seeming … racist.”

“We’re an African American firm being persecuted by a majority-white department,” Adrian Boseman (Delroy Lindo) — one of the three name partners at Reddick, Boseman & Kolstad — adds after the firm’s own lawyer suggests Lucca may not be wrong. “You want us to turn our answers toward race.”

“What do you think?” he asks fellow partner Barbara Kolstad (Erica Tazel).

“About using race?” she responds quickly. “Well, it is about race.”

The aforementioned Mike Kresteva, played by a sinister Matthew Perry, is a government lawyer tasked with reducing the number of police brutality cases brought against the city; his craven plan is to discredit the law firm that most often represents clients bringing suits against law enforcement. Kresteva’s mission against Reddick Boseman builds slowly throughout the season, and Sunday night’s episode finds the firm’s lawyers facing a grand jury after repeated attempts to thwart Kresteva fail.

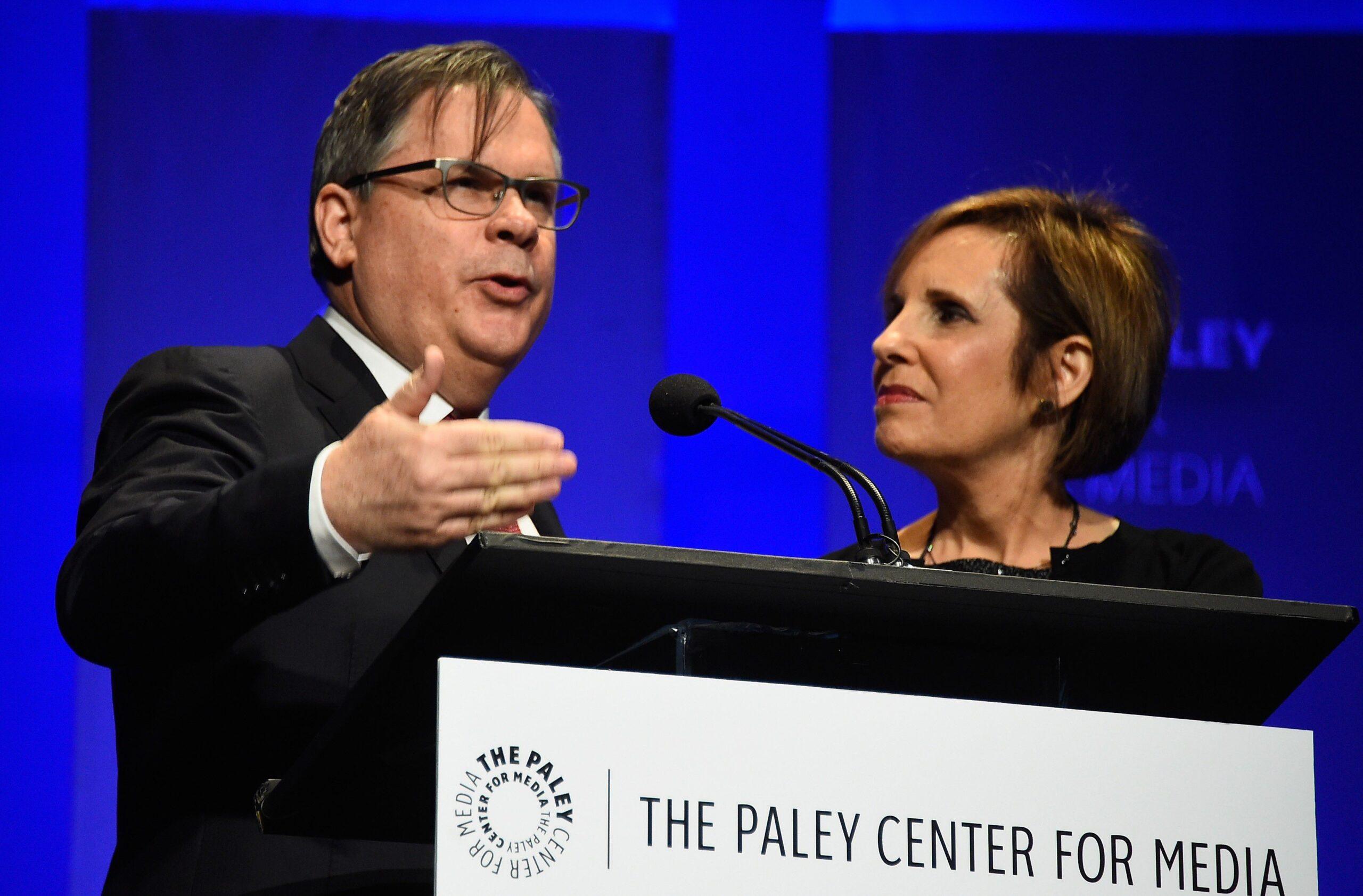

The lawyers’ discussion about whether to name race as a motivating factor of Kresteva’s case is representative of The Good Fight’s major strength: examining the law itself and explicating the context in which it’s applied. The CBS All Access show, which debuted in February, is a spinoff of the network’s successful drama The Good Wife; the premise takes one of its predecessor’s most beloved characters, Diane Lockhart (Christine Baranski), and, after a series of financial and social catastrophes, puts her at the historically black firm Reddick, Boseman & Kolstad. The result is a cultural shift that the staunchly liberal — but definitely still white — Diane finds herself negotiating differently each episode. “This [shift] felt like a way to have [the protagonists] meet characters they haven’t met before [and] see Diane in a fresh situation [while still remaining] firmly grounded in the law,” cocreator Michelle King said when we spoke on the phone recently. Her husband and fellow cocreator, Robert King, who helmed The Good Wife alongside her, added that the decision also simply “felt like an interesting way to address the [internal] politics of a law firm.”

Over the course of The Good Wife’s run, the show handled an increasing number of cases involving the state’s troubled interaction with black people, most often law enforcement. The finale of its sixth season even saw protagonist Alicia Florrick taking on infamous Chicago police “black site” Homan Square, an episode ripped from headlines in the way the Kings do best. But The Good Fight’s Reddick Boseman doesn’t dip its toes into these kinds of cases occasionally the way Alicia’s various firms did; one of the firm’s primary sources of income is representing clients in brutality cases against the Chicago Police Department. The stakes are different here; these cases are quite literally a matter of life and death. Focusing on a primarily black firm offers the Kings an avenue to explore pressing social issues through the perspectives of people more directly affected by them — –and complicates the white, liberal world of the show’s predecessor. The Good Fight’s black lawyers are especially captivating and complex, rare traits for black characters on The Good Wife (with the exception of Mike Colter’s Lemond Bishop). They disagree both personally and politically, and The Good Fight is better for that tension; the firm’s internal heterogeneity highlights the obvious truth that groups of black people are, in fact, not monolithic.

“I think the show is about the racism of liberals,” Robert King said. “I think it’s an easy thing to point to the racism of rednecks and conservatives and the people in the South and so on; I thought what was interesting is that Chicago is such a liberal town, and there is so much kind of limousine liberal racism.” Where The Good Wife addressed race primarily through subplots (like the ongoing controversy around Peter Florrick’s discriminatory hiring patterns), The Good Fight takes a better-integrated (though not always perfect) approach. Main characters like Diane stumble with unconscious bias, and the scenes in which she does are especially didactic. Quiet forms of discrimination are woven into each episode; there is a keen sense of awareness that the unintentionally racist comments a tech CEO makes toward his black lawyers cannot be fundamentally separated from the rampant hate speech on his platform. If The Good Wife challenged the notion of the innocent political bystander, then The Good Fight extends the reach of “politics” well beyond the halls of civic power.

“Part of [the goal with The Good Fight] was showing how people are polite in other ways and then in fact still recognize that there is this racial divide that affects their opinions, affects their willingness to work with each other,” said Robert King. “And that felt very interesting to approach in a firm.” Diane’s fall from grace comes after a Madoff-like Ponzi scheme run by her old friend robs her of her retirement funds and her status at the many liberal organizations she’d unwittingly referred to the scheme. Reddick Boseman is the only firm that takes a chance on Diane, talented and experienced though she may be. Boseman explains the decision to hire Diane by telling her the shady fund never courted black investors; their indignities may not be identical, but both are personal.

The show tackles Diane’s own biases most often through her interactions with Kolstad. Kolstad is wary of Diane from the start; there’s a scene early in the season when Kolstad tells her new colleague — in less than complimentary terms — that she once saw her lecture on diverse hiring. (Diane attempts to lighten the mood by joking that she hopes she didn’t embarrass herself too much; “Not too much,” Kolstad replies, tight-lipped and apparently unamused.) Kolstad is especially upset that Diane brings two white women with her to the firm instead of interviewing the many black women applicants Kolstad had arranged for her.

Kolstad, who must contend with intersecting forms of discrimination as a black woman, is a particularly sympathetic character. When Diane brings on an old client, tech CEO Neil Gross, he makes T-shirts to celebrate his company, ChumHum, joining the Reddick, Boseman & Kolstad family. The only name he misspells is Kolstad’s. Kolstad wants the best for her firm, so she heeds Boseman’s laughing admonition to let the misspelling slide. The show frequently highlights her thankless emotional work — a labor that is vital to the survival of the firm and frequently ignored because of its association with femininity. Robert King noted that the dynamic between Tazel’s Kolstad and Lindo’s Boseman feels directly “in dialogue with the old show”: “Delroy [and Tazel are] very much versions of what Will Gardner and Diane Lockhart were in The Good Wife.” That bond is part of what enables them to survive slights both obvious and perhaps unconscious, like every interaction with Gross that isn’t shepherded directly by Diane. Gross, who was a temperamental figure even on The Good Wife, also offers a particularly amusing opportunity for The Good Fight’s white characters to reflect on their own relationship to race and the firm writ large: “Sometimes even the characters in the scene will say, ‘Look, we’re the only white people here and we’re satirizing the ChumHum guy who comes into the office and says, Oh, I love that this is a black firm,’” Robert King said of the T-shirt scene. “It’s a satire of somebody who can only see the firm as African American.”

Kolstad’s discomfort with Diane ebbs and flows, but watching Diane respond to no longer being a name partner, and answering to a black woman in particular, draws out the simmering tension the Kings wanted to highlight: “It’s interesting to see a main character like Diane no longer be at the very top of the heap in this new workplace [and grapple with] what it means to be a subordinate as opposed to the one making all the decisions,” Michelle King said.

But beyond subtle interpersonal racism, the show also addresses the forms of systemic discrimination that plague both Reddick Boseman’s lawyers and the clients they represent. The first episode’s police brutality case hinges on video evidence discovered late into the trial; footage from the police-operated body cams cannot be viewed because the officers never turned theirs on. The nonexistent body-cam footage is an eerie representation of the fears of black people who are exhausted by news of yet another person dead at the hands of supposed law enforcement; the case itself raises anxieties black people feel about policing and government bureaucracy under any administration. Subsequent episodes trace the stories of retail employees whose wages are illegally garnished and a woman fighting for access to an ovum she once donated. Each episode finds clients seeking Reddick Boseman’s counsel for reasons ranging the entire moral spectrum: Union employees are thrust into Reddick Boseman’s portfolio by virtue of a contract intended purely for optics; a tech CEO contracts the company to draft his site’s terms and conditions because he wants the publicity of having worked with an African American firm to address hate speech. It’s not just obvious bullies like Kresteva whose actions belittle Reddick Boseman’s work; The Good Fight examines and critiques discrimination in multiple forms.

In their writing of the show, the Kings are driven by progressivism and also basic narrative considerations. “We had done some research on African American–owned firms, and [the fact] that there was a pragmatic reason to have these firms, not just an idealistic one, which is that they were open to no-bid contracts from government,” Robert King said. “And there were awards for people who gave money or hired them, so that felt like a very practical [consideration] because the show never wants to live in idealism. It kind of wants a pragmatic bone in its body, too.” In an earlier episode, Boseman and Kolstad remind a client of the same when they address his failure to pay the firm for their services. Immediately after raising concerns about how the new administration is affecting his board’s business decisions, the client callously reminds Boseman and Kolstad they “are not the only minority-owned business.”

The Good Fight is at its best when it leans into its own clever, idealistic conceits. In Episode 3, some of the most entertaining moments surrounds the revelation that Reddick Boseman lawyer Julius Cain had voted for Trump. His defection from the firm’s progressive politics allows them to repitch themselves to the aforementioned reneging client, but it causes a massive rift within the firm itself.

“We thought that Julius Cain, played by the wonderful Michael Boatman, was culturally conservative, in that he was pro-life, probably Catholic upbringing,” Robert King said. “He thought Trump was the better way to go. To everybody else in the firm, all they can do is stare at him, mouth open, like what?! … And there might even be other African Americans in the law firm who will not admit they voted for Trump.”

The Good Fight’s exploration of intracommunity dynamics — in this case, what happens when someone votes in a way that’s perceived as being against the larger group’s interests — is both sharp and entertaining. Lindo, Tazel, and Boatman in particular offer hilarious, incisive performances. (“I think people feel a level of betrayal with a Trump vote that they wouldn’t have felt with a McCain vote,” Michelle King added.) Their characters grapple with questions of authenticity and loyalty: Is it selling out their community if they have Cain pitch the firm as Trump-neutral or even Trump-positive when courting that high-profile client? Will this new administration change everything about the way they do business, or do they need to make only a few concessions?

For the Kings, the new show’s attention to politics simply reflects the changing world it is intended to depict: “I think given that The Good Fight takes place in the era of this new administration … the people I know in life are talking more about politics than they were, say, three years ago,” Michelle King said. “So it seems natural to me that our fictional friends are also talking more about politics than they would’ve been three years ago.”

And in keeping with both national and community trends, The Good Fight’s protagonists harbor a skepticism toward the law that even the more jaded Good Wife characters rarely exhibited. The show’s new backdrop — a reality in which calcified political and legislative norms are shifting, affects each episode. Whether it’s the introduction of a Milo Yiannopoulos avatar (played excellently by John Cameron Mitchell) or the trial of a TV writer whose show is ripped from the air for being too critical of the president, The Good Fight takes on the law with a sense of skepticism even The Good Wife’s most corrupt characters never did. (Even Diane’s approach to the law changes; though she’s still zealous as ever, she is visibly shaken by injustice at several junctures.) “Even though the show is not like a teardown of Trump, it’s not like watching Stephen Colbert every night, I think more about the culture has changed,” Robert King said. “The culture is different; you have to address fake news more than you might have before, and you have to address conspiracy theories more than you would [have].”

“Who wins in [a given] case is usually the one who gives the more truthful speech. In The Good Wife it was always ‘Who tells the better story, even if the story’s a lie?’” Robert King said. “Now the world is there, so how does The Good Fight address that when the world has taken over our arena?”

The Good Wife’s fundamental principles of civic engagement and political chess don’t apply to weary black lawyers who have undoubtedly seen some things in their day, who know firsthand that the nation’s most foundational legal documents were not written with them in mind. How they handle the new world they’ve been thrust into — and the new white women trying to figure it out alongside them — makes for television that feels at once grounded and deeply entertaining. The Reddick Boseman lawyers are just trying to figure things out, and it’s fascinating to watch Diane go along for the ride.