Share the Fantasy

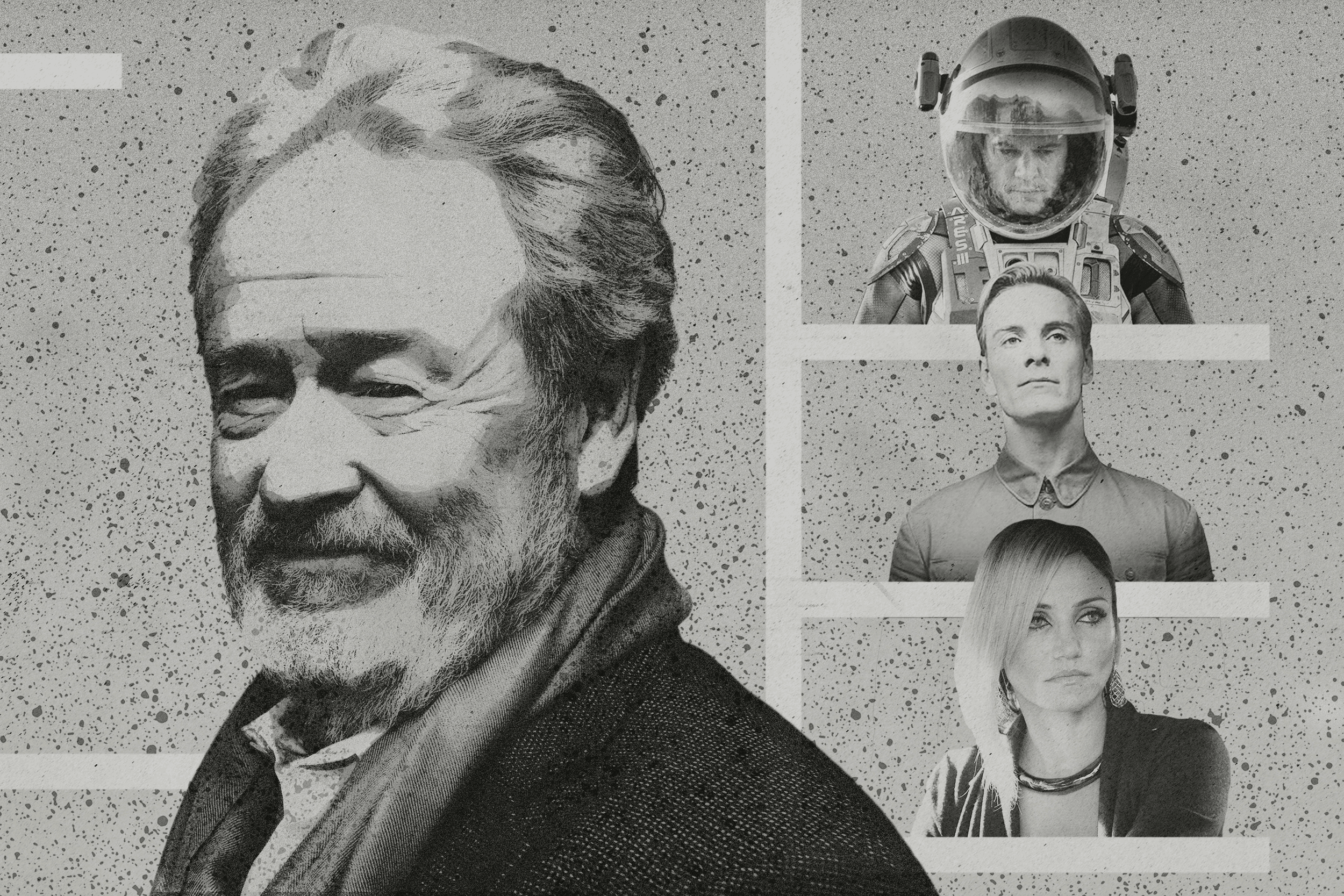

No one brings a scary, new world to life like Ridley Scott, and no one clutters those worlds with thin characters and bloated ideas like Ridley Scott. To mark the release of ‘Alien: Covenant,’ we look at the late period of one of our most brilliant and banal filmmakers.

At the beginning of Alien: Covenant, the screen is filled by a close-up of an eye. It belongs to David, the bottle-blonde android played by Michael Fassbender who has, improbably and provocatively, replaced Ellen Ripley at the center of the most durable sci-fi franchise this side of Star Wars. Besides indicating that this chapter of the story is going to be told from David’s point of view — from behind blue eyes, as it were — the shot recalls the opening sequence of Blade Runner, which also starts by reflecting a replicant’s unwavering gaze back at the audience.

“The picture keeps [Rick] Deckard — and us — fixated on eyes,” wrote Pauline Kael of Blade Runner in 1982. She was picking up on the film’s emphasis on perception, whether enhanced, obscured, or destroyed altogether, as when technocratic puppet master Tyrell (Joe Turkel) gets his peepers ripped out of their sockets by Rutger Hauer’s naughty neo–Pinocchio Roy Batty.

Beneath its layers of future-shock architecture and neo-noir homage, Blade Runner endures mostly as a series of metaphors on vision. Or, as Roy says with his his dying breath: “I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe.”

That line — which, according to legend, was improvised by Hauer on set after he found the dialogue in David Peoples’s original screenplay wanting — also doubles as the last word on Ridley Scott’s filmmaking. It’s been 40 years since he won Best Debut Film at the 1977 Cannes Film Festival for The Duelists, and he’s crafted more than his share of indelible images since. Not just in Alien and Blade Runner — arguably the two most stylistically influential sci-fi films of their era — but also the uncanny flyover-country lunar landscapes of Thelma and Louise; the neon fantasia of Black Rain; the frenetic shaky-cam combat of Black Hawk Down. Even an abjectly terrible movie like Hannibal features the unforgettable sight of Anthony Hopkins performing cranial surgery on Ray Liotta at the dinner table and feeding him his own gray matter.

At this point, Scott has worked in nearly every genre short of musical comedy (Blade Runner’s coastal early-21st-century dystopia is the closest he’ll ever get to La La Land) and yet his filmography is, in its way, remarkably consistent. The tale it tells over and over again is the story of an eye — of a way of seeing that maintains perfect clarity regardless of what it’s looking at.

In the 1970s, Scott’s eye was on a different kind of prize. Straight out of the Royal College of Art, he was the U.K.’s most sought-after director of TV advertisements, including a famous spot for Chanel No. 5 that featured a woman sprawled invitingly poolside, waiting for a handsome man to dive in and swim her way.

The tagline was “share the fantasy,” and the adroit combination of elements — half-naked, fully toned bodies; flared lighting; Vangelis’s hold-music-of-the-gods soundtrack — succeeded in lulling the viewer into a daydream, a state that was less conducive to deep thinking than the irresistible impulse to buy some perfume. If Hollywood is a dream factory, then Scott’s tactic of dangling shiny objects in the frame made him one of the industry’s great hypnotists. Just let your mind go blank and enjoy the show (or else Dr. Lecter will be along shortly to scoop your brains out for you).

In recent years, however, Scott has undermined his own skills as a trance-former by filling his films with the kind of nattering chatter that undermines the spellbinding quality of his visuals. This was not the case early on, when the severe, smoke-and-steel sheen of films like The Duellists and Alien spoke far more eloquently than their screenplays. Late Ridley — which is to say the films that he’s made since 2007, in the space between his 70th and 80th birthdays — tends to be heavy on talk. Or maybe it’s just that the talk itself that’s gotten heavy.

Roy Batty’s “tears in the rain” speech in Blade Runner endures because it’s the poetic high point of a movie that’s mostly terse and silent. It’s the same reason that we remember sadistic synthetic Ash (Ian Holm) rhapsodizing about the Xenomorph’s perfection late in Alien, when the other characters are too busy running away to reflect on the beauty of the thing that’s killing them off one at a time. Both of these monotone monologues delivered by robots are reflections on the processes of creation — the carefully chosen words of machines who’ve finally met their makers.

This is by no means Scott’s only thematic obsession: He’s also pretty into ancient civilizations (1492: Conquest of Paradise, Gladiator, Kingdom of Heaven, Exodus: Gods and Kings), alpha-male codes of honor (The Duelists, Black Hawk Down, Body of Lies), self-possessed heroines bristling against gender roles (Thelma and Louise, G.I. Jane), and photographing his buddy Russell Crowe in various states of disheveled grumpiness (Robin Hood, American Gangster, A Good Year). It does offer some insight into what makes him tick, however.

It’s understandable that a veteran craftsman working with basically unlimited resources would grow progressively interested in how and why things get constructed. In Exodus …, we see the pyramids being erected at the behest of Joel Edgerton’s cruel Pharaoh; the appeal of The Martian lies in how precisely stranded astronaut Matt Damon uses the limited tools at his disposal to “science the shit” out of his situation.

The contrast in The Martian between the modesty of its hero’s means and the full-scale, multinational, multibillion-dollar rescue mission that gets mounted to bring him home is quite funny. While Scott clearly identifies more with the second cohort at this point in his career, there’s finally a harmonious marriage of handcrafted gadgets and high-tech hardware that’s very satisfying. The same goes for the film’s light, humorous tone (faithfully transposed from Andy Weir’s source novel), which might not fully explain its infamous Golden Globe win for best comedy, a choice that led to the Hollywood Foreign Press Association changing its voting rules, but does account for its superiority to other, more self-serious Late Ridley joints.

Exhibit A: Prometheus, which lays the master-builder subtext on pretty thick. “You know that I will settle for nothing short of greatness or I will die trying,” says industrialist Peter Weylan, played by Guy Pearce in distracting Trash Humper drag, neatly summing up the hubris of a movie that tries to out-Kubrick 2001: A Space Odyssey, while also name-checking T.E. Lawrence and John Milton en route to a reengineered origin story for the Alien universe.

The operative word is “Engineer,” the designation given to the sullen, alabaster-skinned titans glimpsed in the film’s wordless, evocative prologue, who are revealed to be the architects of human evolution — moody monoliths modelled on no less a literary-religious personage than Lucifer himself. “If you look at Paradise Lost,” Scott said in 2012, “the guys who have the best time in the story are the dark angels,” before adding later in the interview that he knew exactly how that allusion sounded: “incredibly, pretentiously intellectual.”

That’s a bingo: Prometheus is about as pretentiously intellectual as movies at its budget level get, even though it’s also unmistakably an example of what Roger Ebert called the “Idiot Plot” (meaning its characters all act like idiots even though most of them are supposed to be brilliant scientists). It’s not that the urge to ask big questions about existence is out of place in the realm of science-fiction, which is historically rooted in a spirit of metaphysical inquiry. The problem is that the answers, when they come, have less to do with God or Darwin or H.R. Giger than the modern economics of big-franchise-world building. All the final act of Prometheus actually confirms is that it’s going to take a few more studio-subsidized prequels to properly sort things out.

The mercenary cynicism of a movie that promises enlightenment only to offer brand extension is a ripe topic for satire, and Scott arguably tried to get there in The Counselor. It’s the weirdest of his late films and, as a result, the one that has amassed the most devoted cult. Anybody who has seen Beneath the Planet of the Apes knows that it’s possible to worship bombs, and the critics who’ve stood up for this star-cross’d thriller — written by Cormac McCarthy and set along the same corridor of cartel deals and contract killings as No Country for Old Men — have said that its radioactive status is a sign of integrity. Scott Foundas, who organized the first ever retrospective of Scott’s work at Lincoln Center in 2012, wrote that “its rejection suggests what little appetite there is for daring at the multiplex these days.”

“Daring” is certainly one word for a movie which features, in no particular order: cheetahs crammed into the back of an SUV; a motorcyclist being sliced apart by razor-wire at 200 miles per hour; a tattooed Cameron Diaz impersonating Rihanna; a tattooed Cameron Diaz simulating sex on the windshield of a car; bodies being dissolved in vats of acid; and one of the most famous actors on the planet being decapitated in broad daylight by a mechanical bolito device.

All of these memorably eccentric touches, are in the service of a stark, fable-like narrative about a shady lawyer (Fassbender) who gets inveigled with drug dealers only to find that some deals can’t be reneged on. The film is a critique of unchecked greed that’s nevertheless steeped in signifiers of luxury. Lounging by her five-star hotel’s pool, Diaz’s malign Malinka could be the star of that old-school Chanel ad, and Fassbender’s portentously unnamed attorney rocks designer fashions even when he’s wracked with despair. The contradiction of The Counselor is that it’s an awful lot of fun to look at, provided you can tune out McCarthy’s dialogue, which frequently borders on self-parody. “The world in which you seek to undo the mistakes that you made is different from the world where the mistakes were made,” advises an underworld sage played by Rubén Blades, while Fassbender tries his level best to look like his mind has been blown wide open.

In The Counselor, Fassbender is mostly on the receiving end of speeches. In Alien: Covenant he gets to give them — solemn disquisitions on creation that serve mostly to set the audience up for a late, semi-effective shift into the kind of visceral, predator-prey horror show that Scott pioneered in the first place. Whether or not Alien: Covenant is much of an improvement over Prometheus, it’s equally suggestive of what’s impressive and frustrating about a director whose eye remains sharp even when he can’t see what’s wrong with his own big, beautiful, insufferable movies.