Late in life, Jerry Garcia took up scuba diving. He was introduced to the sport by Vicki Jensen, a friend and former ranch hand of Garcia’s bandmate, Mickey Hart. This was Hawaii, sometime in the late ’80s. Garcia had recently come out of a diabetic coma and was so fat that he had to carry extra weight to help achieve buoyancy, but he loved the water and the water asked nothing in return.

The experience spawned a fixation. Garcia took classes, bought gear, outfitted his goggles with prescription lenses. Later he set a record at the local scuba shop, Jack’s Diving Locker, by staying under for 109 minutes on one tank of air. "I can’t do exercise," he told Rolling Stone in an interview from 1991. Compared with his music with the Grateful Dead, Garcia’s interviews were refreshingly frank. "I can’t jog," he went on. "I can’t ride a bicycle. I can’t do any of that shit. And at this stage of my life, I have to do something that’s kind of healthy" — "this stage," in other words, meaning the end.

The story — about Garcia falling in love with the ocean, about the ocean as a place where Garcia could both reconnect with the world and retreat from it — is told in nearly every account of the Grateful Dead. Bill Kreutzmann, one of the band’s drummers, opens his memoir, Deal, with a scene of him and Garcia diving. Phil Lesh, the band’s bassist, writes about how he and Garcia shared a special bond over their total uninterest in exercise — that is, until Garcia convinced him to dive. You can see footage of the man in the water in The Other One, a documentary about the band’s cofrontman Bob Weir. Garcia glides through the water like he belongs there. He paddles up to an eel cautiously emerging from a coral hut and strokes it under its chin like a housecat. It’s remarkable to see a fat man move with such grace, not to mention a man of so many prisons — addiction, success — move so freely in a place where nobody knew his name.

But the most telling instance of Garcia’s diving history is from the September/October 1995 issue of People Magazine. Part of a tribute issue printed a month after Garcia died of a heart attack, the story catches up with Vicki Jensen and the staff at Jack’s Diving Locker, recounting Garcia’s early encounters with the water and his and the band’s financial commitments to the restoration of coral reefs, invoking Garcia’s rich sense of humor, and closing with the requisite speculation that diving might’ve made his short life just a little bit longer.

Substitute another name for Garcia’s and you can see how routine the story is: a lost star’s difficult attempt to reclaim solid ground. Flip, then, to the magazine’s cover, a picture of Garcia looking into the camera with his sunglasses lowered, lit from behind so as to create a halo at the edges of his hair. To understand how big the Grateful Dead had become by the time of Garcia’s death, how grossly saturated in the culture, look here. Other People cover subjects that season included Courteney Cox, Princess Diana, and a double issue called "The Year of the Big Splits," promising "an inside report on Hollywood’s divorce epidemic." You see why Garcia went under in the first place.

The scuba story comes up again in Long Strange Trip, a new documentary about the band directed by Amir Bar-Lev and due to be released Friday by Amazon Studios. At four hours, the movie is probably more exposure than many people have ever had — or wanted — to the Grateful Dead. It’s also a sad story, and a beautiful one, told with the reverence you’d expect and some poetry you might not. Split into six sections, it follows the band from the back of a pizza parlor in Menlo Park to stadiums so large they could no longer make out the faces of the people they were playing to. For all the journeying they did, the band always seemed to boomerang to Northern California, a place once synonymous with the counterculture and now — through decades of evolution — with the entrepreneurial frontier of Silicon Valley.

Garcia grew up alongside the beat generation, taking special inspiration from Jack Kerouac’s unbroken ream of typewritten pages — a predecessor to Garcia’s own guitar solos, which, like Kerouac’s writing, analogized a creativity so expansive it threatened to break the page. (Or, in a more Freudian light, here were men who could go all night long.) The beats were famously interested in speed; the Dead were famously interested in LSD, a drug that at the band’s inception was so off the cultural grid that nobody had bothered to make it illegal.

The way Long Strange Trip tells it, the impact of the drug on the band’s creativity was seismic. At their most enlightened, Grateful Dead performances, like acid, break familiar shapes into protozoan states, squiggles of guitar filigree and synaptic splashes of drums that seem to predate known musical forms that the band then bends — sometimes remarkably, sometimes with great injury to patience — back into something you can tap your foot to. No wonder people come out of hearing things like the Cornell 1977 performance of "Scarlet Begonias" into "Fire on the Mountain" thinking the band are gods: The music dramatized evolution.

For 20 years, they were primarily an underground concern. They put out records that — with the exception of the folksy, atypically simple American Beauty and Workingman’s Dead — most people didn’t buy, and instead focused on live shows, seeding an audience that by the late 1970s and early 1980s had become so complex and multifaceted as to warrant anthropological study. (As Neurotribes author Steve Silberman puts it in Long Strange Trip, Dead shows were like a mandala — a Hindu or Buddhist diagram of the cosmos — with the band at the center.)

Like all good stories about art — or about entrepreneurs, for that matter — Long Strange Trip becomes a parable about people who succeed in part by doing it wrong. Not recorded but live. Not scripted but improvised. Not concision but sprawl. Not entertainment but journey. Even when the band adapted to the times — the hillbilly jazz of the early ’70s, the disco Dead of a few years later — they seemed happily out of step, a talisman against business, fashion, and other methods of control.

The movie ends with Garcia’s death, while the other surviving members have soldiered on in various — and often multiple — Dead-centric reparatory groups, including the Other Ones, Furthur, Dead & Company, and Phil Lesh and Friends. After an extravagant 2015 tour publicized as the final time the band’s surviving original members would play together, a group of them are about to go out again. Whether you see the temporal scope of the movie as implicit criticism or just acquiescence to logistics probably depends on what you think of the idea of John Mayer singing with the Grateful Dead, which begins this weekend and will be happening throughout the summer and likely for some summers to come. For his part, Garcia famously said the band had been trying to sell out for years but nobody was buying. If a French exit is leaving without saying goodbye, the Grateful Dead have found its opposite.

Long Strange Trip follows certain conventions of the rock documentary. There’s the moment when the band becomes too big for its members to handle and the moment when the drugs stop being fun. There’s the suggestion that the band transcended the confines of reality and were eventually grounded for ignoring them. It makes its subjects look like decent people, or at least people chastened by the passage of time.

The portrait is as selective as any. For all the ideals surrounding the band’s music, the day-to-day culture seemed macho and banal. In his biography of the band (called, incidentally, A Long Strange Trip), longtime publicist Dennis McNally quotes Bob Weir as saying that the band’s early benefactor (and LSD manufacturer) Owsley Stanley could "abuse a waitress like no one else in the world." Bill Kreutzmann’s memoir, Deal, contains a story wherein Kreutzmann has sex with 13 women in a row and another in which he blows cocaine while suspended upside down in an Alfa Romeo he had crashed seconds earlier. (You don’t have to snort the coke if you’re already upside down.) One of the most salient images in Long Strange Trip isn’t of the band but their crew, a fraternity of bruisers who spent all night fucked up beyond cognizance, setting up and breaking down the band’s 75-ton sound system before trucking it to the next show. How any of them drove goes unexplained. "If you’re looking for comfort," Garcia said in 1991, "join a club or something. The Grateful Dead is not where you’re going to find comfort. In fact, if anything, you’ll catch a lot of shit. And if you don’t catch it from the band, you’ll get it from the roadies. They’re merciless. They’ll just gnaw you like a dog." Initially, the back cover of the 1970 album American Beauty was supposed to be a photograph of the band, heavily armed.

The band presented as socialists but the core of their philosophy was libertarian. Garcia, for example, was outspoken about drugs being a matter of personal choice, a convenient position for a heroin addict. Three months after a member of the Hells Angels stabbed a concertgoer to death at the Altamont Speedway, Garcia told an interviewer that the Hells Angels "happened because of freedom. They’re free to happen, you know, and they’re a manifestation of what freedom is" — the idea being that freedom isn’t good or bad, just free, while rules remain the currency of parents and cops.

Toward the end of Garcia’s life, the band’s shows got so chaotically overattended that the members issued an open letter. One request was that people without a ticket stay home. The second was that people don’t show up just to sell stuff, because that attracts people without tickets. The third — broadly applicable — was that the true Dead Heads help keep the phonies in line.

"Want to end the touring life of the Grateful Dead?" one line reads. "Allow the bottle-throwing gate crashers to keep on thinking they’re cool anarchists instead of the creeps they are." One fan in Long Strange Trip protests that they’re only doing what the Dead taught them. I ask Eric Eisner, the movie’s lead producer, what he thinks about this. "I get it," he says. "It’s an ethos. It’s like utopia: It doesn’t work in reality, but on paper it looks great." His first Grateful Dead show was on December 9, 1988, at the Long Beach Arena — the last time the band played there on account of (in Eisner’s recollection) too many people camping outside. In a perverted, Shakespearean way, this is how things had to go down.

The saddest story in Long Strange Trip is about Garcia’s late-in-life reconnection with Barbara Meier, a girlfriend Garcia had not seen since before the Grateful Dead were even called the Warlocks. It was Meier, a beautiful teenager making a pre-inflation-$100-a-day modeling for catalogs, who bought Garcia his first guitar. The relationship — in the telling, at least — is one of irreconcilable innocence, the point from which our best selves spring and to which we can never safely return. (In a Victorian flourish, Dennis McNally writes that Garcia remained "remorseful" for taking Meier’s virginity even 20 years later — because what are women if not angels or whores?)

According to Meier, she and Garcia reconnected after McNally pressed her to interview Garcia for the Buddhist magazine Tricycle. He made her laugh. He invited her scuba diving. She went. He proposed. She accepted. He was such a beautiful diver. At the time, Garcia was clean. He started using heroin again shortly thereafter. When Meier approaches Garcia about his relapse (something she finds out from his doctor), Garcia severs the relationship. Her parting shot is of him standing in a doorway saying, "I think you should go now." An addict until the end, Garcia seemed to have a knack for making neglect look like a favor to the neglected. What the movie doesn’t cover is that Garcia was married to another woman, Deborah Koons, within a year, or that, as McNally writes, he told Barbara Meier and all four of his wives that they were the loves of his life. And it certainly doesn’t talk about the bitter disputes surrounding Garcia’s estate. Nobody wants to be the boss.

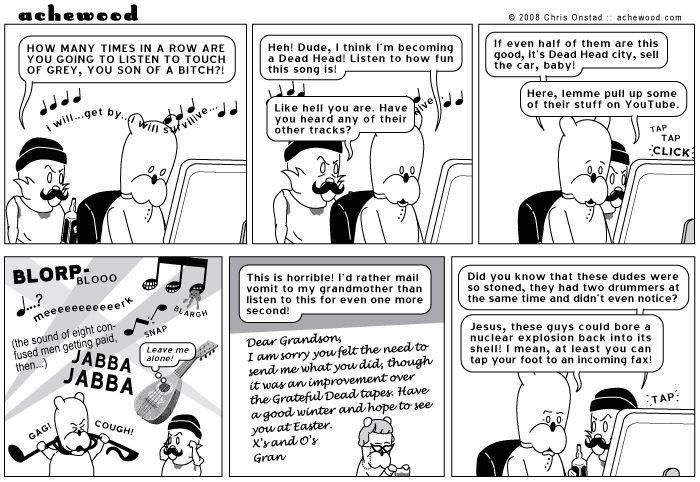

As for that music. The sharpest criticism of the Grateful Dead I’ve ever read was in the online comic strip Achewood. In it, a bear named Téodor sits in front of his computer listening to "Touch of Grey" on repeat. "Grey," which came out in 1987, was the band’s only quantifiable hit, a slick, feel-good song about — what else — keepin’ on. An alcoholic tiger named Lyle storms into the room and demands Téodor turn the song off. Téodor refuses. "Dude," he says. "I think I’m becoming a Dead Head." Lyle recommends he listen to a few more of the band’s songs on YouTube.

What follows is the visual articulation of what I imagine is a common response to the band’s music. Spotlights in every direction. A string of musical notes, some grinning, one vomiting. A lute with a thought bubble coming out of it reading "Leave me alone!" Téodor struggling with a musical note wrapped around his neck, either choking himself or being choked. Hovering near the middle, slightly tilted, a parenthetical that reads "(the sound of eight confused men getting paid, then…)."

The shape and volume of the space is unclear — it literally has no form. The parentheses, the ellipses, the word "then" — all of it nauseatingly inconclusive, signs that nobody really knows what’s going on but whatever it is, it’s going to go on forever. Kreutzmann said the band sometimes stretched the music out so far that he had to be reminded what song they were playing.

The Grateful Dead always had a dark side that I loved. The skulls split by lightning bolts. The laughing gas. The homeless kids camped out in vans babbling about angels. The way everything tilted toward chaos. When I think of the Grateful Dead I think of the man standing behind the stage at the Veneta, Oregon, show in August 1972, naked and sunburned, shaking his head as though trying to get a better signal. I don’t laugh at the man, I worry about him. If this is freedom, keep me caged, but let me watch.

It’s hard to find this vector in the band’s music. Even the darkest passages of the Grateful Dead sound like the shallow side of the deep end. These were people who shared good times with dangerous men. To date, five of their members have died. If they ever felt angry, or trapped, or like throwing a brick through a window, you’d never know it from their music. Maybe this is why the punks hated them so much: They pretended violence didn’t exist.

My favorite Grateful Dead song is "Black Peter," from Workingman’s Dead. The song tells the story of a guy lying in bed with a fever. He’s pretty sure he’s going to die, but he doesn’t. Maybe he’ll die tomorrow. Either way, he feels a little out of it. Everything seems important ("See here how everything lead up to this day") and then not ("and it’s just like any other day that’s ever been"). "Take a look at poor Peter, he’s lying in pain," Garcia sings toward the end. "Now, let’s go run and see." It’s an eerie moment, the glimmer from behind a dark door. He repeats the line — "run and see" — and the music dilates, then fades away.

According to The SetList Program, a searchable database of Grateful Dead shows covering 1965 to Garcia’s death in 1995, the band played "Black Peter" live 343 times, among the top 20 in their repertoire. It usually came toward the end of the night, though it was never the last song — too ominous, too inconclusive. Headyversion, a community site ranking fans’ favorite live versions of Grateful Dead songs, currently puts a performance from October 29, 1977, at the top. It’s all right but doesn’t seem to understand why it exists. My favorite — March 25, 1990 — comes a little further down the list, at no. 6. Garcia coughs and wails. The band plays like they’ve been chained to the wall of the same sports bar for 200 years. The sum is a report from the void: haggard, luminous, undead.

It’s in these late groupings of "run and see" — the way the song gathers into a wave but never breaks, the way Brent Mydland’s organ melts from solid into liquid and solidifies again — that I glimpse what I always imagined this band was: the good time that isn’t, the night you get so far out you’re not sure if you’re still there. Garcia once told an interviewer he never bothered going into the woods to take acid because it only showed him how pretty things were. His favorite trip was the one that peaked with him continuously dying. In 1986, he fell into a diabetic coma for about five days. By then, he took psychedelics only once in awhile to, in his words, "blow out the tubes." He preferred heroin. In 1970, "Black Peter" was a dream; in 1990 it was a diary.

My own introduction to the band was through a guy I grew up with. Let’s call him Mark. Mark and I met on the tennis team, where we were briefly doubles partners. He was a sinister kid, spoiled and mixed up, said awful things about girls and talked constantly about how much he hated his "old man." Mark didn’t laugh, he cackled. We used to speed around the backroads of southern Connecticut in his BMW convertible drinking beer and listening to tapes of the Grateful Dead live. The music made no sense to me. It had no urgency, no imperative. I felt like Téodor the bear, drowning in a sea of broken notes. Mark said I was a pussy and that the Dead were the fucking best.

This was my first association with the band: not the curious, openhearted hippies of the late 1960s but emotionally damaged kids who drove sports cars. Mark, I learned, was not unique. I met dozens of guys like him in college: preppy, conservative, intelligent but incurious, zigzagging across the lawn to "Franklin’s Tower." Even the ones not obviously racked with darkness would say things that made me realize they thought poor people were trash or gay people were sick.

What people whose lives had been defined by the exclusionary levers of privilege got out of music so inclusive was beyond me. If they were anything like Mark, their privilege didn’t do much to make them feel at home in the world. Not that any of this was the band’s fault, of course. Only to say that I showed up in 1998 and found the dream in tatters. Maybe their open letter had been right. I learn now that Mark is serving a six-to-eight-year sentence for getting drunk and crashing his Porsche Boxster, killing a 25-year-old in the passenger seat. You who choose to lead must follow, but if you fall, you fall alone.

The way Long Strange Trip tells it, two encounters haunted Garcia for most of his life. One was with the Watts Towers, a cluster of sculptures in South Los Angeles built by a local using scrap metal and rebar. Garcia first saw the towers around dawn after the Watts Acid Test. He couldn’t figure out why anyone would want to make anything so permanent. It was still on his mind nearly 10 years later. "The County of Los Angeles couldn’t pull the towers down," he told an interviewer. "So they made them a park. They wanted to destroy them."

His other hound was the movie Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein. He first saw it when he was 6, about a year after his father had died from drowning. It scared him so badly he could barely look at the screen. (Dennis McNally writes that Garcia spent so much time looking at the seat in front of him he could still remember the pattern of the fabric.)

Long Strange Trip turns the Frankenstein fixation into a motif, cutting footage from the movie into the narrative at moments of synchronistic resonance, the idea being that the monster was on Garcia’s mind even when it wasn’t. Like Charles Foster Kane and Rosebud, the suggestion here is that we spend our adulthood turning our hearts into fortresses but can’t ever protect ourselves from the aftershocks of youth. Half watching Frankenstein behind the seat in front of him, Garcia formed a concept of fear not as something to avoid but as the point of seduction, the gantlet between you and the unknown.

Talking about his acid/death epiphany, Garcia said, "It started to get more and more in kind of a feedback loop, this thing where I was suddenly in the last frames of my life. And then it was like, ‘Here’s that moment where I die.’ I run up the stairs and there’s this demon with a spear who gets me right between the eyes. I run up the stairs there’s a woman with a knife who stabs me in the back. I run up the stairs and there’s this business partner who shoots me." Die that often and it’s no wonder you feel weird about permanence.

And yet here stands a four-hour-long documentary made from film and magnetic tape telling the story of a band whose reluctant leader claimed no goal other than to ride the transience of a beautiful moment but kept returning to Frankenstein, to the idea of the Watts Towers, to the ocean. Garcia’s lapse in understanding here was a mortal one: You don’t build monuments outside time; time builds them inside you.