On May 24, Orioles first baseman Chris Davis came up with two outs in the eighth, two runners on, and the O’s trailing the Twins by one run. Left-handed pitcher Taylor Rogers started the slugger with three consecutive curveballs, two of which were likely in the strike zone but all of which were called balls. Up 3–0 with the tying run in scoring position and a righty on deck, Davis was in an enviable spot, almost certain to get something to hit.

Here’s how the rest of the plate appearance played out:

Davis saw six pitches from Rogers, the last three of them strikes, and he never swung. Davis didn’t suffer from any incorrect strike calls; according to Pitch Info data, the three strikes had called-strike probabilities of 92.5 percent, 96.8 percent, and 98.9 percent. Add in the earlier calls that went the Orioles’ way — the first two called balls were 76.1 percent and 63.2 percent likely to be strikes, respectively — and Davis took five probable strikes in a single plate appearance. Rogers got out of the inning, and the Orioles lost.

Although Mets fans are still scarred by Carlos Beltrán’s NLCS-ending take from 2006, there’s nothing inherently blameworthy about a called strikeout. Sometimes — as in the Beltrán example — a great pitcher throws a great pitch that a hitter can’t handle. And patient hitters have to accept some called strikeouts as the cost of working the count.

Davis, though, is taking called strikeouts to an unprecedented extreme. After striking out looking 56 times in both 2014 and 2015, he set an all-time single-season record last year with 79 punchouts, breaking the previous record of 72 set by Jack Cust in 2007. (Cust is the only other hitter ever to top 67.) And Davis seems determined to obliterate his own record this year. The average hitter this season has struck out looking at a rate that would translate to 30 punchouts per 600 plate appearances. Davis has already been rung up 35 times in just 208 plate appearances, putting him on pace for a ridiculous 109. The 11-strikeout gap between Davis and the next-most-frequent looking-K victims of 2017 — Keon Broxton and Ryan Schimpf, who are tied with 24 — is as big as the gap between those two and the 11 hitters who are tied for 39th place. Davis is the king of caught looking. And while striking out isn’t awful in the abstract, he can’t hit homers if he doesn’t swing.

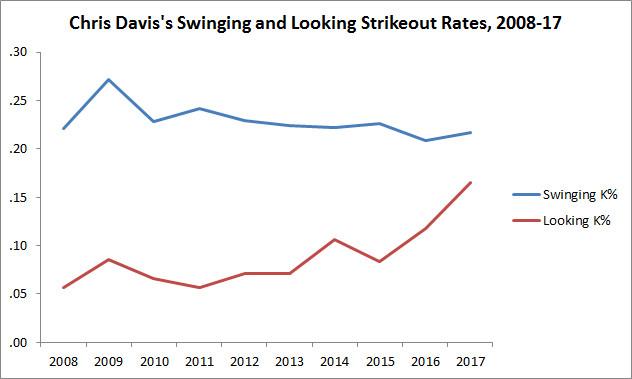

At 38.2 percent, Davis’s overall strikeout rate this season would be a career high for him, and trails only Broxton’s and Joey Gallo’s among qualified hitters. But his looking-K total isn’t simply rising in proportion with his overall rate — in fact, it’s completely causing his strikeout increase. As a percentage of his plate appearances, Davis doesn’t strike out swinging any more often than he did at the dawn of his career. But since last season, when his looking-K rate began to creep up, he’s struck out looking more often than ever.

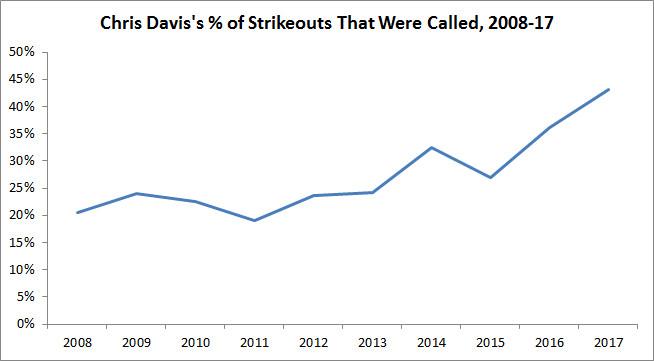

The lines representing Davis’s swinging- and looking-strikeout rates are close to crossing. This year, 43.2 percent of Davis’s strikeouts have been called.

Only five hitters have ever had called strikeouts account for a higher share of their K’s while qualifying for the batting title: Rickey Henderson in 1993 and the strike-shortened 1994 season, Luis Castillo in 2009, Brett Gardner and Bobby Abreu in 2010, and Matt Carpenter in 2014. That quintet came from a mold that Davis doesn’t fit: Aside from Henderson in ’93 and Abreu, those hitters homered eight times or fewer. All five posted on-base percentages of at least (and in most cases, well above) .352, and all except Carpenter stole at least 20 bases. In those seasons, at least, they were hitters who didn’t punish pitchers with power. They took close pitches, worked their way on and, with the exception of Carpenter, threatened to steal. It made sense for them to be so selective because they didn’t do that much damage when they did make contact.

Davis, who is bigger than all of those guys, isn’t even close to the same sort of hitter, so if he finds himself in an exclusive club with Castillo it’s probably a bad sign. Davis, who’s batting .230/.325/.475 with 12 home runs, hasn’t been a horrible hitter this season, but he’s dropped below the first-baseman baseline; his park-adjusted production has been only 12 percent better than the MLB average, compared to the typical first-sacker’s 16 percent edge. Davis doesn’t offer much value in the field or on the bases, so he’s only an average-ish player unless he’s really raking. In 2013 and 2015, he was among the best hitters in baseball, leading the majors in homers both years, but he’s fallen far from those heights through the first season and a third of the seven-year, $161 million free-agent deal he signed in January.

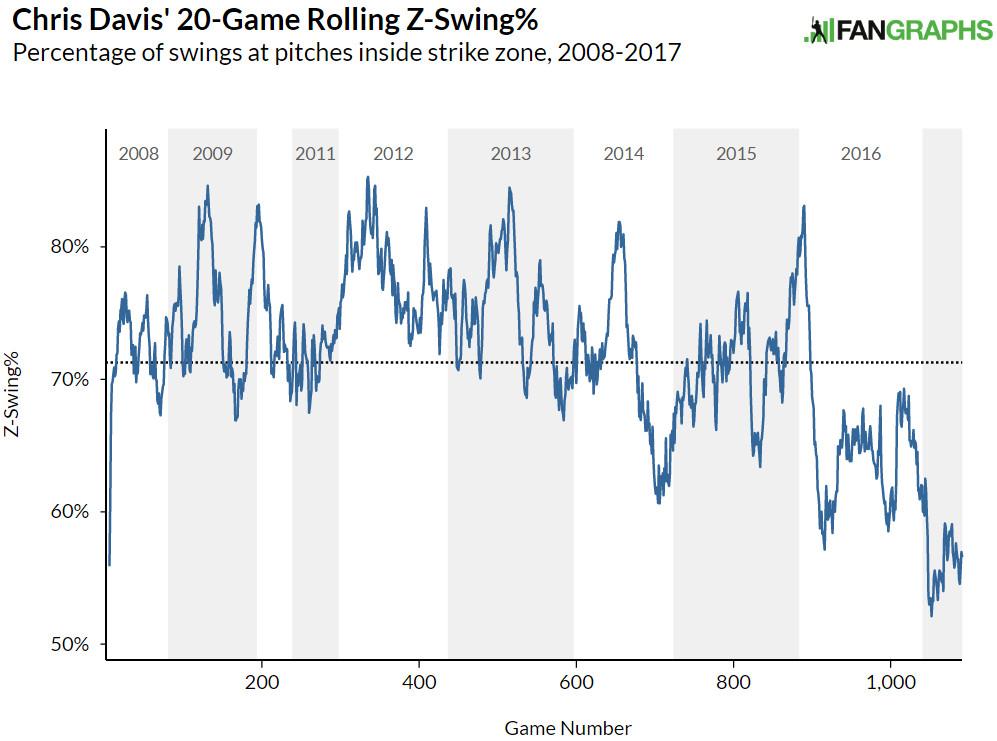

Davis’s looking-strikeout totals are really just a symptom of the core cause of his struggles — an apparent collapse of his grasp of the strike zone. Not only is Davis swinging at out-of-zone pitches more often than he has in several years, but he’s swinging at strikes significantly less often than he ever has — less often, in fact, than all but six other qualified hitters. A few weeks ago, I wrote about a stat I call “selective aggression,” which measures the ratio of a hitter’s in-zone swing rate to his out-of-zone swing rate. A higher ratio indicates that a hitter is swinging at presumptive strikes while letting likely balls go by. The “Percentile” column in the table below shows how Davis stacks up to other MLB batters (minimum 130 PA in previous seasons and 40 PA in 2017).

Davis has never been among the best by this metric, but as recently as 2015, he placed in the middle of the major league pack, ranking in the 49th percentile. This year, though, he’s sunk all the way to the first percentile. That low ranking is the result of consecutive seasons in which Davis’s zone-swing rate has plummeted.

Among hitters who qualified for the batting title in both 2015 and 2016, only Joe Mauer saw his swing rate at pitches inside the strike zone drop more than Davis’s. And among hitters who’ve qualified for the batting title in both 2016 and 2017, only Jonathan Schoop and Corey Seager have exceeded Davis’s decrease. (Thanks to Schoop, Davis, and Adam Jones, the O’s have fallen from fourth in zone-swing rate in 2016 to 21st this season.) After nearly leading the league in zone-swing-rate decreases in back-to-back years, the middle of Davis’s swing-percentage heat map looks a lot less red than it did during his last big offensive season, as the GIF below reveals.

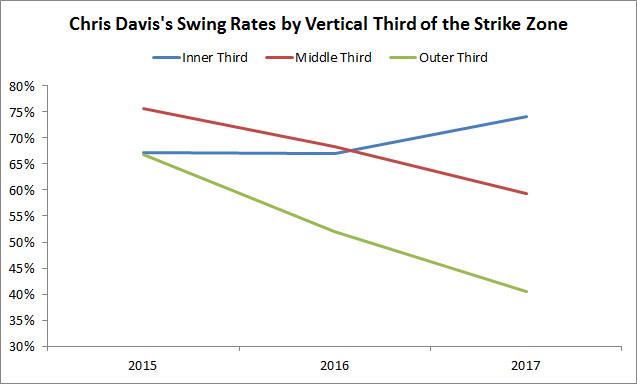

Those images make it clear that Davis is still swinging as often as ever at pitches on the inner third; in fact, he’s offered at even more of the inner-third pitches he’s seen in 2017 than he did in 2015. Over the middle and the outer thirds of the zone, though — areas in which he crushed the ball in 2015 — he’s letting many more pitches go by. Among left-handed hitters, only Mauer has swung less often this season at pitches over the outer third.

All of those extra takes on middle-out pitches are a recipe for called strikes and, in turn, called strikeouts. To make matters worse, pitchers seem to have noticed that they can get away with throwing strikes to Davis: Baseball Prospectus’s plate-discipline stats say he’s seeing more pitches inside the strike zone than he has since 2011, the year before his breakout in Baltimore.

On the surface, the solution to Davis’s called-strikeout scourge seems simple: Just start swinging at strikes again! Maybe a mindset change or a minor mechanical tweak is all it would take; Davis doesn’t seem to be setting up any farther away from the plate than he used to, but he did seem to close his stance slightly this week before hitting homers in back-to-back games.

But maybe those missing swings are also a symptom. Davis says he’s trying to be aggressive, but he admits that he’s had trouble picking up pitches. After striking out eight times in a recent series against the Astros, he sounded like someone who might need a referral from teammate (and LASIK success story) Seth Smith. “I feel like I was not really recognizing the pitch until it was right in front of me, but at that point it’s too late,” Davis told reporters. “Anytime I’m taking that many called third strikes, something’s going on because I’ve never been one to really lay the bat on my shoulder.” It might also be that at 31, he’s laying off more often because he’s not quite as confident in his ability to flick outside pitches out of the park as he did during his best years. In a period when leaguewide exit speeds and launch angles are increasing, Davis’s average values have dropped by 2.8 miles per hour and 1.7 degrees, respectively, relative to 2015.

Even in his current incarnation, Davis isn’t an easy out, but his passivity in the strike zone is making him more exploitable. Not so long ago, Davis led the major leagues in long balls. Now he’s leading only in looking strike threes.

Thanks to Hans Van Slooten of Baseball-Reference for research assistance.