Wasted Talent

After his turns in ‘A Bronx Tale’ and ‘The Sopranos,’ Lillo Brancato had stardom at his fingertips and lost it all in a haze of drugs and a violent crime. Does he deserve a chance at a comeback?One Saturday afternoon in the spring of 1993, Robert De Niro visited the Yonkers home of Lillo Brancato for lunch with his family.

Brancato, the 17-year-old soon-to-be star of De Niro’s directorial debut, A Bronx Tale, was living a dream. He grew up idolizing De Niro, not least because he’d been told that he resembled the two-time Academy Award winner. He loved De Niro’s films and would routinely reenact scenes from Raging Bull and Goodfellas with his brother, Vincent. When Cape Fear was released in November 1991, Brancato even grew out his hair and scrawled crude tattoos on his skin to mirror the Southern backwoods look of De Niro’s Max Cady. He also developed an uncanny De Niro impersonation — which was how he was discovered.

On July 5, 1992, a casting scout seeking a fresh face for the role of Calogero, De Niro’s son in A Bronx Tale, was handing out flyers on Jones Beach when he approached Vincent. He declined, but recommended his older brother. Lillo then emerged from the surf and immediately launched into his De Niro shtick for the video camera — the "You talkin’ to me" scene from Taxi Driver. The next day he visited De Niro’s office in the Tribeca Film Center. Less than two months later Brancato was on the Astoria, Queens, set of A Bronx Tale, making his acting debut in a movie directed by his hero.

De Niro and his young star grew close during filming, with De Niro often huddling with Brancato and Chazz Palminteri, the film’s screenwriter and costar, after hours in his apartment to review scenes. And so De Niro had arrived at the Brancato home, a six-bedroom brick house that Lillo Sr., a contractor, had erected in 1987, for more than a home-cooked meal of pasta and meatballs. He was there to deliver a warning.

Sitting at the head of the dining room table, De Niro charmed his hosts, often slipping into Italian during conversation. He called Lillo’s dad "Mr. Brancato" and complimented him on the espresso, which was served with homemade cookies and pastries from the fancy bakery. He then turned to Lillo. "Your life is going to change immensely and you have to be careful with who you surround yourself with," he told him. "You have no idea what’s coming. You have to make smart decisions. Please, be smart."

Brancato shrugged off the advice. "A kid at 17 handpicked to be in Robert De Niro’s directorial debut thinks they’re invincible," Brancato says today. "You don’t know better at that age. Only later on in my life when I ended up incarcerated did I realize I’m not invincible."

A Bronx Tale received overwhelmingly positive reviews when it opened in September 1993, with Siskel & Ebert, Entertainment Weekly, and Rolling Stone singling out Brancato for his performance as Calogero, or "C," as he was nicknamed. From there, he traced the standard trajectory for an emerging star, signing with William Morris and landing parts in big studio films.

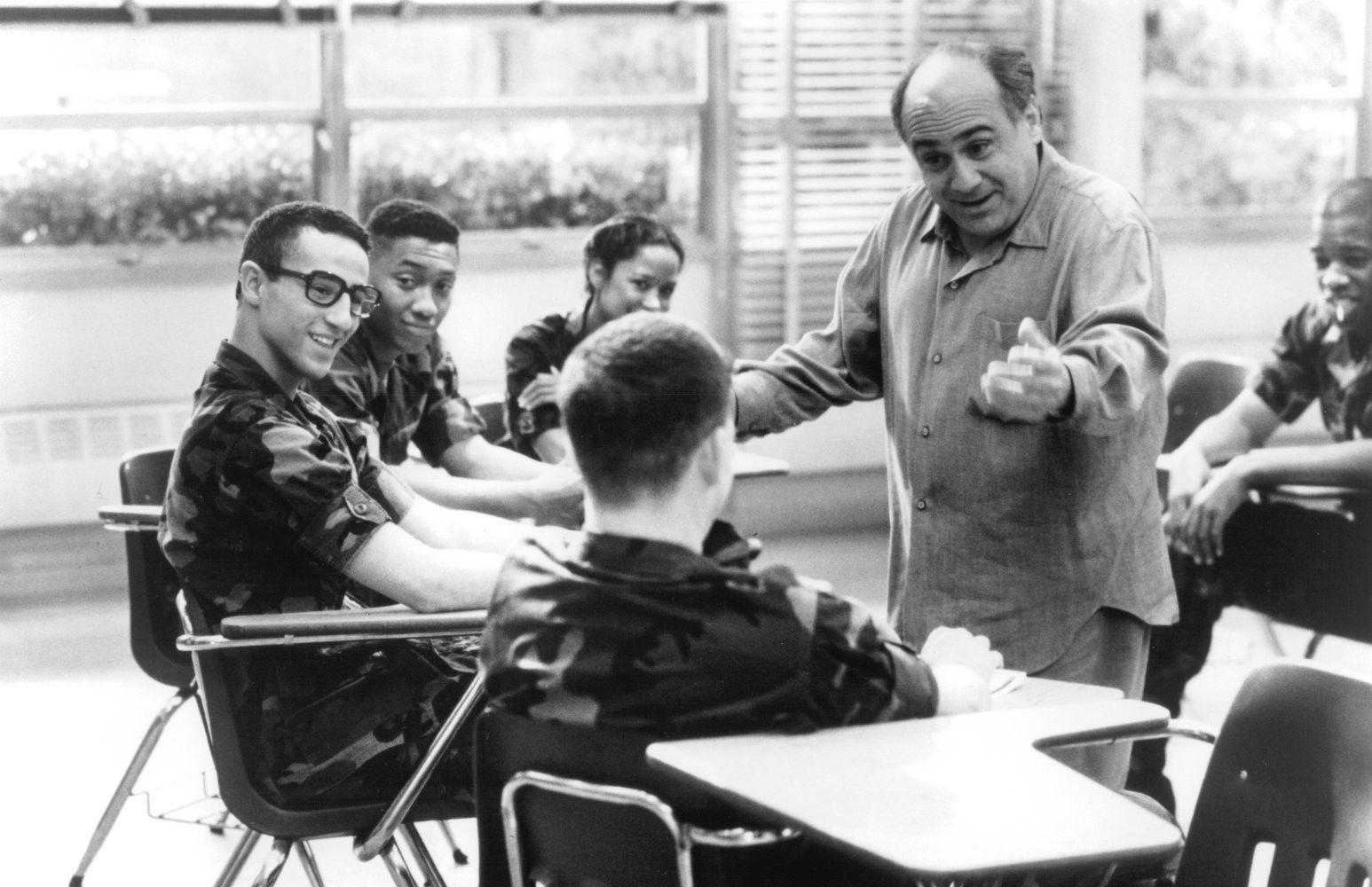

Brancato secured a supporting role in the 1994 Danny DeVito comedy Renaissance Man after De Niro showed an early print of A Bronx Tale to his Awakenings director, Penny Marshall; Marshall ensured that Brancato’s Raging Bull impersonation made its way into the film. As Benitez, the four-eyed private, Brancato showcased his goofy charm while maintaining a hint of street smarts.

Then Brancato saved the world from nuclear holocaust opposite fellow Westchester County native Denzel Washington in the 1995 Simpson-Bruckheimer submarine blockbuster Crimson Tide. Brancato initially passed on the role. "It was summertime and I didn’t want to work," he remembers. "But my agent was like, ‘Lillo, they want you in this.’"

He soon began making even more questionable decisions, his promise vanishing in a fog of drugs. Because stardom had come so easy, he thought, it would always be that easy. It wasn’t, and it wouldn’t. Brancato began to struggle to find work, even with a high-powered agency behind him. Hollywood moved on to the next big thing. Brancato moved on to pain pills and cocaine, and, later, to snorting heroin and smoking crack.

Like most teenagers, he began experimenting with drugs out of curiosity. It quickly escalated. "I know what it’s like to be in the depths of hell and to be hooked on that crack pipe to the point where you don’t want to smoke, but you feel like there’s a magnet pulling your lips to it," he says. "It’s a place I never thought I’d get to, and everyone warned me about it."

A six-episode guest stint on The Sopranos in 2000 bore the makings of a comeback, but the actor spiraled further into addiction. Brancato hit bottom on December 10, 2005, when an aborted break-in left an off-duty NYPD officer dead; Brancato, who was shot twice in the incident, was convicted of attempted burglary and served eight years in prison.

Seated at a Yonkers pizzeria one June afternoon, he still resembles De Niro in a way that’s impossible to ignore. The mole on his right cheek is the clincher. Brancato is solid and compact, with sad eyes, a square jaw, and a shaved head — like many balding men, he is obsessed with his hair, or what’s left of it. He works out for at least two hours a day and eats clean on weekdays. He is concerned with things like the vascularity of his biceps. "I guess I’ve replaced one addiction with another," he cracks.

Brancato wears a black Gennady Golovkin T-shirt and a pair of dark jeans that hug his coiled frame. Even his sneakers — black-on-black Air Jordan IIIs — look a size too small. He occupies the corner table near the window, watching the high school students and senior citizens come and go. Occasionally, he’ll recognize a familiar face from this deep-rooted community, less than 10 minutes from the house where he grew up.

Brancato, still a youthful-looking 41, is now attempting to reclaim a career that peaked over two decades ago, while also maintaining his sobriety and accepting his role in the death of a 28-year-old police officer. He is a work in progress. "You do the best with the hand you’re dealt — this is what I got now. I can’t change it. I can’t go back to the C days," he says. "This is life after C, you know?"

As far back as Brancato can remember, to his childhood in Yonkers, he craved attention and used humor to attain it. He was the class clown in school and at family functions, where he’d ape Uncle Joe, Aunt Lina, and Rocco, a family friend. Making people laugh felt like a special power at times. A thing, it seems, he still needs.

Over the course of two hours in the pizzeria, Brancato impersonated his girlfriend’s mom, his father, Louis Mandylor in My Big Fat Greek Wedding, Canelo Alvarez, Paulie Walnuts, Woody Allen, Plaxico Burress, Johnny Depp as Whitey Bulger, James Gandolfini’s character in True Romance, Gandolfini as Tony Soprano, De Niro as Jimmy the Gent, and — De Niro’s favorite Brancato impersonation — Frankie Pentangeli from The Godfather: Part II. He is prolific to an almost extreme degree, with an ability to mask his distinct tone — a hard rasp on top of a thick outer-borough accent — during his send-ups.

Brancato reminds me of the kids I grew up with in Queens, brash neighborhood guys you’d find at a bodega skimming the Daily News while waiting for their bacon, egg, and cheese. He brandishes a hucksterish charm, the product of punctuating his anecdotes with the assertion that, yes, these are all true stories. He also picks weird moments to name-drop. "This guy looked like Buscemi for a second," Brancato says about a man with slicked-back hair dumping his crust into the garbage. But there is a genuineness to him that belies his bluster.

Brancato was born Saul Rodriguez in Bogotá, Colombia, to parents he never met. The circumstances around his adoption are difficult, yet familiar. After a miscarriage, the Brancatos contacted adoption agencies before finally adopting the baby who’d later be known as Lillo Jr. During this time, Domenica Brancato learned she was pregnant. Four-month-old Lillo arrived at the Brancato home in January 1977. Vincent, a self-described "miracle baby," was born in May.

Growing up in an Italian immigrant family — Lillo Sr. is Sicilian; mom is from Calabria — the boys were, well, boys. But Lillo had a troublemaking streak, and he was thrown out of Sacred Heart High School at the beginning of 10th grade for his antics; he completed sophomore year at Roosevelt High School in Yonkers. A few days later, he visited Jones Beach with his brother and his cousins. Life would never be the same.

"Fame," Brancato tells me, "was very overwhelming, especially in New York City."

It was the mid-1990s and, initially, Brancato enjoyed the spoils of fame: free food, free drinks, free clothes, free entry to the hottest clubs in the city — Limelight, Palladium, Tunnel, Expo, Veruka, Webster Hall, and Supper Club. Everything was comped. There were women — a lot of women. He partied with Heidi Fleiss’s call girls and had a tryst with a Scores stripper. And when drugs entered the picture, his entourage expanded.

"There were a lot of hangers-on. A lot of them were suppliers," says Louis Vanaria, the actor-singer who played Crazy Mario in A Bronx Tale. He and Brancato remain friends. "The best way to be Lillo’s friend at the time was to have drugs on you — then you were automatically his friend. When he got in with that [wrong] crowd, I kind of separated myself from him."

The drugs quickly affected his career. Brancato didn’t read scripts, didn’t work on his craft. He blew off talk show appearances and meetings — big, important meetings, like one with Steven Spielberg to read for the Vin Diesel role in Saving Private Ryan; Brancato had been partying all night and slept through the 10 a.m. appointment. The movie business is simultaneously big and also quite small. Word spread fast: Brancato was unreliable.

He still landed work — the Sopranos stint; some indie films; a walk-on, essentially, in Enemy of the State, directed by Crimson Tide’s Tony Scott. But work and drugs became intertwined. If he got a part, he’d celebrate by drinking and disappearing into a three-day crack binge. If he didn’t get a part, he’d disappear into a three-day crack binge. He was often high on set, sometimes holding back the vomit until a scene ended.

His addiction deepened. In June 2005 he was arrested on a charge of heroin possession. He was almost killed in an Atlantic City crack house. Once a good-looking, healthy kid, he shrank to 132 pounds. The family staged an intervention and shipped him to rehab; Brancato lasted a day. "He didn’t care who he was hurting," Vincent Brancato remembers. "That’s why I just gave up. I said, ‘You know what, dude? Go kill yourself, because that’s what you’re doing anyway.’ … We got into a fight and I was throwing him around like a rag doll. I stopped talking to him afterward."

In December 2005, Brancato went to a Bronx strip club with his ex-girlfriend’s father, Steven Armento, a burglar with three convictions. Brancato says they occasionally hung out because he was still in love with Armento’s daughter. On that night, Brancato, already high on coke and heroin, was looking for more drugs. With his regular dealer unavailable, he says he devised a plan: He’d score Valium from an acquaintance, a Vietnam vet named Kenneth Scovotti who lived in nearby Pelham Bay. But when he didn’t answer the door, Brancato broke a window. Scovotti had actually died in July.

Shortly after 5 a.m., a next-door neighbor, off-duty NYPD officer Daniel Enchautegui, heard the window shatter. He called 911 and left his home to investigate. Gunfire was exchanged in an alleyway, and Enchautegui was killed when Armento shot him in the chest with his .357 Smith & Wesson revolver. Brancato, who was unarmed, was shot by Enchautegui during the firefight; he’d eventually lose his spleen and part of his colon.

He remembers his first night in Rikers Island. Brancato was in the medical dorms, which, he says, were enclosed by plexiglass windows. People stared. He felt like an animal in a zoo. One inmate tapped on the glass to get his attention and then started rapping 50 Cent’s song "Wanksta," but with a twist: "Damn homie / In A Bronx Tale, you was the man, homie — what the fuck happened to you?"

Brancato was not amused. "Drugs!" he shouts now. "That’s what happened to me."

Brancato continued using in Rikers Island, even overdosing on four bags of heroin and 25 morphine pills on November 12, 2006. He started on the path to sobriety shortly afterward. Still, he was in despair. Friends didn’t write or visit. He was facing life in prison, alone and without hope.

The trial was a tabloid sensation. Brancato hired high-powered defense attorney Joseph Tacopina, a flamboyant litigator with a nose for famous clients and television cameras. Brancato says that prosecutors offered him a plea deal of 15 years, but Tacopina insisted on going to trial, where the case hinged on whether the jury believed Brancato’s testimony — that he was unaware Armento was armed that night. In December 2008, he was found not guilty of second-degree murder, but convicted of attempted burglary. Later he was sentenced to 10 years in prison; Armento is serving a life sentence for murder.

Brancato maintains that had he been acquitted, he would have gotten high that night. "Three years at Rikers Island was not enough," he says. "I believe that was a sentence imposed by God. That was the amount of time needed to get where I’m at today." Brancato is now more than 10 years sober.

He learned how to survive in prison. The rules were simple: Mind your business. Pay your gambling debts. Never discuss your case. Do not pretend to be something that you’re not. Brancato played his position. He was the funny guy. But when tested, as was the case during an argument over phone time, he got physical. "He threw his punches. I threw mine. From what I was told, I got the better of him," Brancato says of the altercation. "When a guy says something like, ‘If you don’t like it, then do something,’ you kind of have to do something. It can get worse if you don’t nip it in the bud."

Not every inmate was hostile. During his time at the Oneida Correctional Facility, Brancato became workout buddies with former New York Giants wide receiver Plaxico Burress, who was serving 20 months on a gun charge. Sometimes they played catch. "I got a decent arm. I can throw a 20-, 30-yard spiral," Brancato says. "I think he was talking about me on one of the talk shows. He said, ‘You got guys up there who thought they were John Elway.’ No, Dan Marino, that’s my guy!"

For the most part, he lifted weights, played dominoes, and read. Brancato completed his GED and got a degree in business management while in prison. He was paroled on December 31, 2013, having served eight years of his 10-year sentence.

Brancato says he has reentered society a different person. The height of his fame — the "C days" — were fun and lucrative, but had stunted his emotional growth. He was a kid who starred in movies and then developed a drug addiction. Not only did prison save his life, it transformed him into an adult. He moved out of his parents’ house in September 2014 to live with his girlfriend, whom he met on Instagram while incarcerated. Brancato says he is a model parolee, always home by 9 p.m. He attends meetings at St. Ann’s Catholic Parish, where he had his confirmation as a kid.

But there are some who will never forgive Brancato. "There are people that I grew up with, people that loved me, who want no part of me nowadays," he says. "I’ve seen people in stores — someone will notice that it’s me and they’ll pull their kid closer to them. Fuck outta here with that bullshit."

New York Police officers have been among his toughest critics. Some cops look at him and spit on the floor, he says. Brancato accuses police of pressuring a Long Island restaurant owner into canceling a meet-and-greet he had scheduled. (The NYPD did not respond to requests for comment for this story.) And then there were the calls in 2015 from Pat Lynch, head of one of the city’s police unions, to boycott the boxing drama Back in the Day after Brancato was cast in the film. The tabloid news, along with Lynch’s rhetoric — calling Brancato a "junkie" and "thug" in a heated statement — reinforced Brancato’s image as a pariah.

It’s an image that Brancato struggles to manage himself. On the one hand, he says he has helped many experiencing addiction since his release from prison, including family friends and strangers on Instagram. (He shows me the DMs of those he aided.) Then again, he straddles the line between oblivious and tasteless when discussing those good deeds. "I sometimes look at this guy [Enchautegui] as my angel, like he gave up his life for mine, for me to help other people."

But he also takes full responsibility for his role in Enchautegui’s murder. "Someone is dead because of my drug addiction," Brancato says. "I think about that night every day." Not long after, he absolves himself of some of that responsibility when he notes, again and again, that he wasn’t armed when Enchautegui was killed. (Efforts to reach Enchautegui’s family were unsuccessful.)

"My lawyer said it best: ‘There were three people there that night. Two were carrying guns. Lillo Brancato wasn’t one of those people,’" he says, raising his voice. "This is the pretty picture that the press painted. ‘You’re a scumbag, a cop killer.’ I’m far from that. How could you say that when if I was there that night by myself doing what I was doing with exactly what I had on my person and you eliminate the other guy from the equation that cop would still be alive. How did I kill this guy?"

When he gets going like this, pleading his innocence all over again, Brancato speaks in long passages. "I don’t consider myself a bad guy," he says at the end of his outburst. "I will be remembered as a good guy. I will be remembered as a real good guy. … I was a drug addict. Some of the best people get addicted."

Unlike most people who peaked in high school, Brancato can easily access his glory days. Like whenever A Bronx Tale airs on cable.

When was the last time he saw the film? "The whole thing?" he asks. "Listen, I’d be lying if I said I was flipping through the channels and it was on and I didn’t look at it, you know?"

A few days after our first meeting we reconvened in Yonkers to watch A Bronx Tale. Standing in front of his place, a sleek luxury building near the Yonkers Metro North station, Brancato expresses reluctance about the screening. "You’re really gonna make me watch the movie?" he asks as we walk along the Hudson River. "It’s like going up to De Niro and going, ‘You talking to me?’ Can we at least fast-forward the beginning with the kid?"

Soon we are in his apartment, a 14th-floor one-bedroom rental with granite counters, a climbing tower for his cat, Mila, and a dazzling view of the Hudson. We settle into his couch and order the movie on Showtime on Demand.

Brancato first saw A Bronx Tale during the summer of 1993, when he and a friend were stranded in Manhattan after an audition. He called Chazz Palminteri, who began performing A Bronx Tale, his semiautobiographical one-man show, in 1989. Before selling the film rights to De Niro, he insisted on writing the screenplay and starring as Sonny, the charismatic gangster who mentors Calogero. When Palminteri heard about Brancato’s predicament, the older actor invited them to his house. After dinner, he asked if they wanted to see the movie. "It was amazing," Brancato remembers.

The memory puts him a better place. We do not fast-forward any scenes. "On the streets of the Bronx," he sings along with the film’s theme song. For the next two hours, Brancato will provide his own commentary for the film, punching in with random facts, memories, and observations.

He points out that the real Eddie Mush played Eddie Mush. He discloses De Niro’s direction to his actors ("If you don’t feel like doing anything, don’t do anything. It’s better to do less than too much"). He names his best scene: the argument with Jane and her brother. And Brancato reveals that he’d smoked a blunt before the memorable "Is it better to be loved or feared?" scene with Palminteri.

"Great scene," he says after Sonny kills the man attacking Joe Pesci’s character. "This was the first day of shooting, August 31, 1992. I was on set for this. You see what Chazz did after pulling the trigger? Chazz, man, fucking perfect. He was fucking perfect, man. He didn’t look a second too long or a second too short. He’s worried. ‘This fucking kid saw us — fucking kid.’ You’re watching this movie and thinking Sonny may try to hurt this kid now. Instead, he takes him under his wing and becomes like his father to him."

Later, Brancato ponders his relationship with the actor. Palminteri, a former Limelight bouncer, treated Brancato well, even taking him on a $500 shopping spree at the Gap before filming started. Like De Niro, he cautioned Brancato about the trappings of fame. And he expressed concern upon learning of Brancato’s drug use.

Brancato and Palminteri kept in touch after the 2005 arrest and even discussed working together on a documentary, which Palminteri planned on titling Wasted Talent. But Brancato says that in 2007 he declined to participate until after his trial. That was the last time they spoke.

Since then, Palminteri has publicly blasted Brancato, most notably in a 2014 Daily News interview after Brancato’s release from prison. "I don’t want it in any way understood that I’m working with him or in contact with him," he told the paper. "I really have nothing to say [to him]." Palminteri declined to comment for this story.

"The disappointment that Chazz has expressed, I totally understand it," Brancato tells me. "If I was him and he was me, I would say, ‘Look what we did. We gave you the shot of a lifetime and this is what you’re going to do.’ I understand that."

A few minutes later, after Sonny’s murder and the Joe Pesci cameo, we watch the final scene. Calogero walks out of the funeral home with his father and, speaking in voice-over, delivers the movie’s most famous line. "The best lessons right here," Brancato says, sitting on the edge of his couch. And then, in the film: "The saddest thing in life is wasted talent, and the choices that you make will shape your life forever."

As the closing credits roll, I ask what those words mean to him today.

"They have real true meaning. A lot of people will never appreciate those lines as much as I do because they never really wasted their talent or made the bad decisions I made," he says. "It’s one of the best examples ever of life imitating art. ‘The saddest thing in life is wasted talent’ is so real. Yeah, I did waste it for some years. But now I’m so hungry and motivated."

Hollywood is littered with redemption tales. Robert Downey Jr. Drew Barrymore. Last year, Mel Gibson was nominated for an Oscar. Their offenses were largely self-inflicted. Brancato’s crime had a real victim: New York Police officer Daniel Enchautegui. His family resists the idea of a Brancato comeback. "It’s always been about Lillo," Enchautegui’s sister, Yolanda Nazario, told the New York Post in 2015 after Brancato was cast in Back in the Day. "Shame on whoever hired him."

Recently, Brancato has been appearing in small independent films, including the upcoming Monsters of Mulberry Street and Fury of the Dragon. Dead on Arrival — a thriller from the writer of the 2015 film Heist, starring De Niro — features Brancato. "In his previous roles, he was very Lillo-esque in a sense, but in this movie you don’t see Lillo, you see a character," says Stephen C. Sepher, Dead on Arrival’s writer and director. He wrote the character with Brancato, his longtime friend, in mind. "I think Lillo’s going to be fine. I think he needs to stay the course and keep the discipline. … He has the chops to do it. I think it’s a matter of the right directors discovering that and him delivering for them."

He appears to be making strides into more mainstream projects, like an upcoming Showtime series for which he just auditioned. Then there are the close calls with a pair of legendary directors. Brancato’s first audition out of prison was for a small part in American Sniper, the Clint Eastwood–directed film that went on to gross more than $350 million domestically. He landed the role — he shows me the confirmation email from his manager — but his parole officer wouldn’t allow him to travel to Morocco for filming.

Then, last fall, Brancato shot a scene for Wonder Wheel, Woody Allen’s upcoming film starring Kate Winslet and Justin Timberlake. Walking on to the film’s Staten Island set, he was thrilled to learn that Jerry Popolis was the hair department head. "That’s De Niro’s hair guy," Brancato tells me. "Best hair guy in the world." From there, it got even better. On set he found Steve Schirripa and Tony Sirico — Bobby Baccalieri and Paulie Walnuts from The Sopranos. Sirico, he says, approached him, pinched him on the cheek, and said, "Welcome home."

"He was very empathetic to me and my situation when I saw him," Brancato says. "That was nice. It made me feel very good." Sirico, who spent two stints in prison, including one for armed robbery, declined to comment through his manager.

Brancato recently learned that his scene had been cut from the film. "What are you gonna do? Smooth waters never make a skilled sailor," he says. "I’m a little disappointed. I would’ve liked to have been in it. But it’s the experience just to say that Woody Allen hand-picked me to be in his film and directed me in a scene. That’s an honor."

These days, he knows what’s important. He attended a funeral three weeks earlier for a childhood friend who had overdosed. Drugs have claimed three more friends from Brancato’s childhood. Any one of them could have been him. Maybe they should have been him, he wonders. Which makes it easier for him to admit that this may be as good as things will get. The "C days" are over. And there might not be a second act.

"Sometimes you have to come to terms with the way things are and you have to accept them," he says. "Believe me, bro, I’ve been through a lot worse. If I’m never going to be in studio pictures again, so be it."