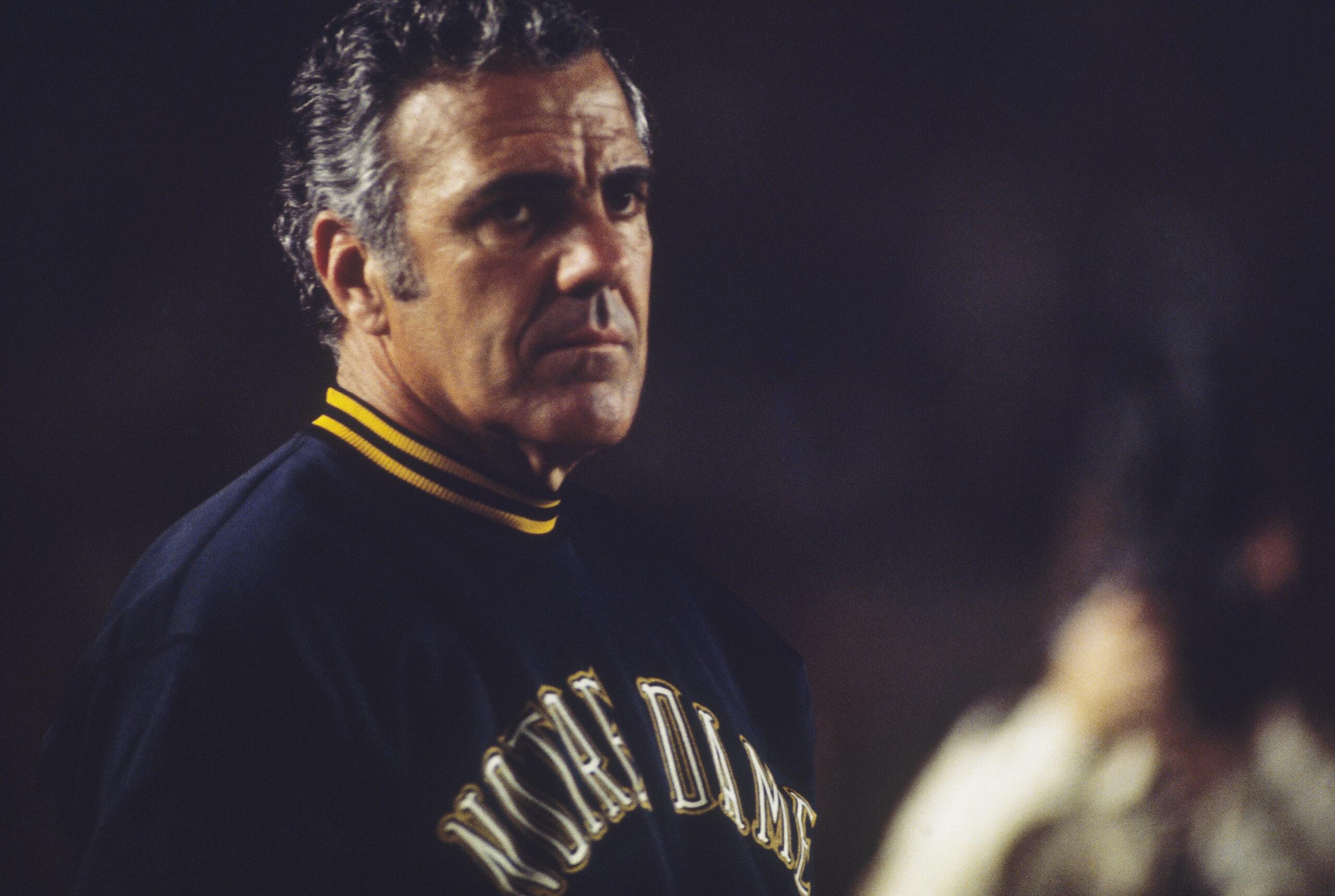

Legendary Notre Dame Coach Ara Parseghian Dies

The Fighting Irish tactician was universally respected

In November 1966, an attorney from Miami sprung for a plane ticket, food, and lodging in New York City, all so that he could watch a college football game on live television rather than on a two-hour tape delay. This is how different the sport was back then: It was largely a regional pastime, with one live, nationally televised game a week. There was only one team that transcended geography, and this was the team that the attorney had traveled north to see — the team that Ara Parseghian had resurrected into a national power after taking the job a couple of years earlier.

Parseghian—who died Wednesday at the age of 94 — was a Johnny Carson–like figure, an almost universally respected coach and a lovable human being who put Notre Dame at the front and center of the national conversation at a moment before ESPN and message-board culture would factionalize everything. When Parseghian took the job at Notre Dame in 1964, the Irish had been in freefall. The eras of Knute Rockne had long since passed, and the subway alumni in New York City, whose only true connection to college football was through Notre Dame, were becoming restless and distracted. Notre Dame had gone 19-30 between 1959 and 1963, and that’s when it took a shot on the son of Armenian and French immigrants who had grown up in Akron, Ohio, coached at Miami (Ohio), and then turned Northwestern into a respectable football program.

The first thing Parseghian did upon his arrival was deliver a rousing pep talk that fired up both the student body and his own roster of players. That was the other thing about the man: He was shrouded in mysticism, but it was not the gruff and hard-assed mysticism of colleagues like Alabama’s Bear Bryant or Ohio State’s Woody Hayes.

Ara’s mysticism was metaphysical: He was the kind of guy you just believed, without him having to shout or curse you up and down the practice field (in fact, Parseghian never cursed). He was fastidious and organized and he paid attention to detail (among other things, he prohibited his players from eating ice cream and gravy in the dining hall); he believed his Notre Dame players suffered from a lack of confidence. One of his former players, the writer and professor Michael Oriard, called him "a charismatic, all-seeing god on the high tower at practice."

All of it worked: In his first season, Notre Dame improved from 2-7 to 9-1, and by that fall the student body was so enamored by his presence that when the cold weather took hold in South Bend in November, they began to chant, Ara, stop the snow! ("Could I?" Parseghian is alleged to have asked his assistants.) He lasted 11 seasons at Notre Dame; he won 95 games, lost 17, tied four, and won two national championships, and by the last game of the 1973 national championship season, when the students again chanted, Ara, stop the snow, even he seemed convinced of his own otherworldly presence. ("Should I?" he supposedly asked.)

And yet it was one of those four ties that proved the most complex, because that tie occurred in November 1966, in the game that prompted that Miami attorney to invent a primitive form of pay-per-view. That day, undefeated Notre Dame played undefeated Michigan State in one of college football’s multiple variations of a Game of the Century. This was in the era before bowl games mattered, an era when the final national polls were essentially popularity contests. Parseghian was very popular, and Notre Dame was very popular, which is why, with roughly 90 seconds to play and the game tied at 10, Parseghian, playing with a backup quarterback who had been recently diagnosed with diabetes, chose to sit on the ball. Notre Dame, with its national profile and its largely white roster, wound up winning the national championship that season; Michigan State, with a largely black roster and a lesser national profile, finished no. 2.

You can argue whether the decision to settle for a tie was the right call from an ethical perspective, but it was the right call from a practical perspective, and Parseghian would defend it for the rest of his life. "We didn’t go for a tie," he would later say. "The game ended in a tie."

Even then, as the social changes wrought by the 1960s sunk in, few could ever question Parseghian’s morality or his ability to relate to his players’ changing attitudes. He won his second national title in 1973, and then, burned out by the demands of the job, he retired after one more season and became a genial television broadcaster and an advocate for a cure for the disease that killed three of his grandchildren. He was on the air as college football became a cash cow for the networks and the cable stations, as it began to grow into a sport where everything is televised — a sport that Notre Dame is still a critical part of, but not in the same way it once was. These days, the best college football coach in the country is a Process-oriented grump who would probably attempt to stop the snow by staring down a nimbostratus cloud; the only coach I can think of who can even approach Parseghian’s level of spiritual charisma is Kansas State’s seemingly ageless Bill Snyder. The era of Ara is long gone now, and so, too, is our belief in the mystics.