The NFL’s Mindfulness Movement Is Spreading

Pete Carroll isn’t the only football decision-maker obsessed with sport psychology anymore. The Falcons, Colts, and 49ers have all also embraced mindfulness training—and their experiences could impact the culture-building dynamic of a league long resistant to change.Positional distinctions are disappearing. Rushing yards are losing meaning. And offensive and defensive schemes are shifting from game to game — if not drive to drive. The most popular sport in America is changing faster than it ever has before — yet the way we talk about the game has largely stayed the same. It’s time for the conversation to catch up to the shifting concepts redefining front offices and gameplay nationwide. So welcome to The Ringer’s You Don’t Know Football Week, where we’ll explore and attempt to better understand the evolutions already occurring on the gridiron — and the reboots we’d like to see make their way to the game next.

The way Russ Rausch remembers it, the discontent took hold about 11 years ago. It was a clear spring day in 2006, and Rausch was sitting in his office at Trading Technologies International on the 11th floor of a building that overlooks the Chicago River. His view from above the Adams Street Bridge was gorgeous, with the Civic Opera House positioned off in the distance.

Rausch, then 42, had been with the company for eight years. He’d watched it grow from around 25 employees to more than 500. His work had taken him around the world, from Southeast Asia to Europe. He was living a dream that would have been hard to fathom as a kid growing up in tiny Clonmel, Kansas; Rausch had become the first member of his family to graduate from college and had made enough money to own a five-acre property in an affluent Chicago suburb and a vacation home in Wisconsin. “[I had] everything I thought I ever wanted, and I felt very empty,” Rausch says. “What’s the point of doing all this crap if you don’t feel any better? That was the initial sort of moment where I felt, ‘Something’s wrong.’”

In his search for answers, Rausch turned to the external factors in his life, leaving Trading Technologies to join a hedge fund in search of new professional heights. It wasn’t enough to alleviate his growing sense of dissatisfaction. In 2012, Rausch sunk to a new low, one that he considers his breaking point. “I’d been [at the hedge fund] for a year and a half and started to realize, ‘This isn’t the answer,’” he says. “I felt even worse.”

Rausch was wildly successful from a career standpoint, but unfailingly unfulfilled—a dynamic that many elite athletes know well. After previous changes failed to make him feel better, he shifted his focus inward, stumbling upon Charles F. Haanel’s book The Master Key System and becoming consumed with its methods of meditation and self-actualization. In early 2013, Rausch launched a website devoted to Haanel’s teachings that ultimately blossomed into a business. Now 53, Rausch has cut his time in finance to only a few hours each week, shaped a company called Vision Pursue, and emerged as one of the leading figures of a movement that’s spreading in NFL circles: mindfulness training.

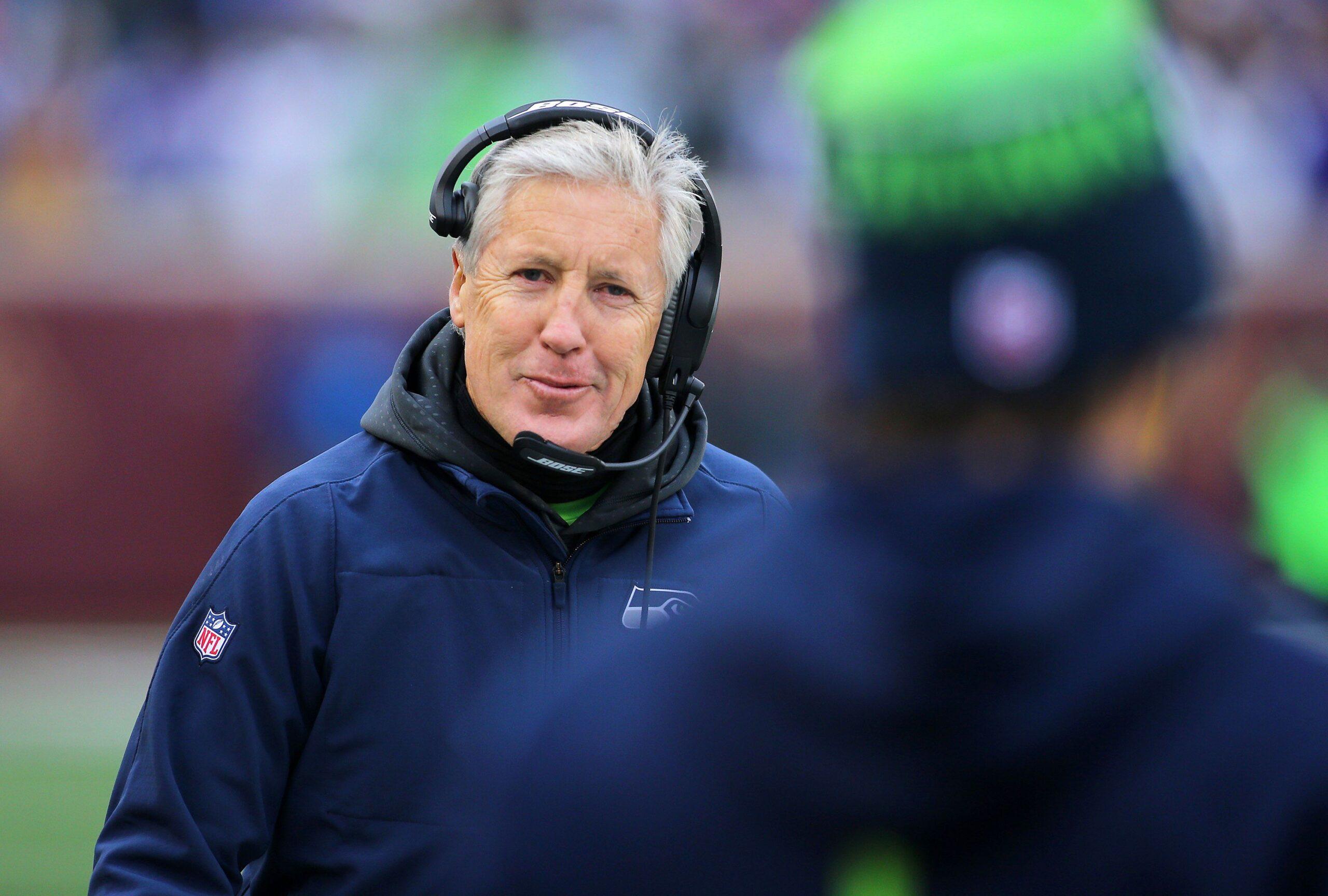

Football culture has been notoriously resistant to new or different thinking, as the NFL has been slow to embrace advanced analytics and to implement changes that could improve player safety. In at least one respect, though, the game is welcoming a philosophy that hasn’t traditionally meshed with gridiron wisdom. Seahawks head coach Pete Carroll has long stressed the importance of mindful experience and seeking out moments of immense mental clarity to improve performance, but up until recently he’s been an outlier. By creating an app to facilitate scheduled meditation and mindfulness exercises, Rausch has provided a resource that espouses similar ideas in a way that fits the rhythm of NFL routines.

[I was] always looking for something else. It’ll be better when … Now, I don’t think in those terms.Dan Quinn

“It’s different way of looking at it,” 49ers head coach Kyle Shanahan says. “It relates more to your daily life. I think it helps our players.”

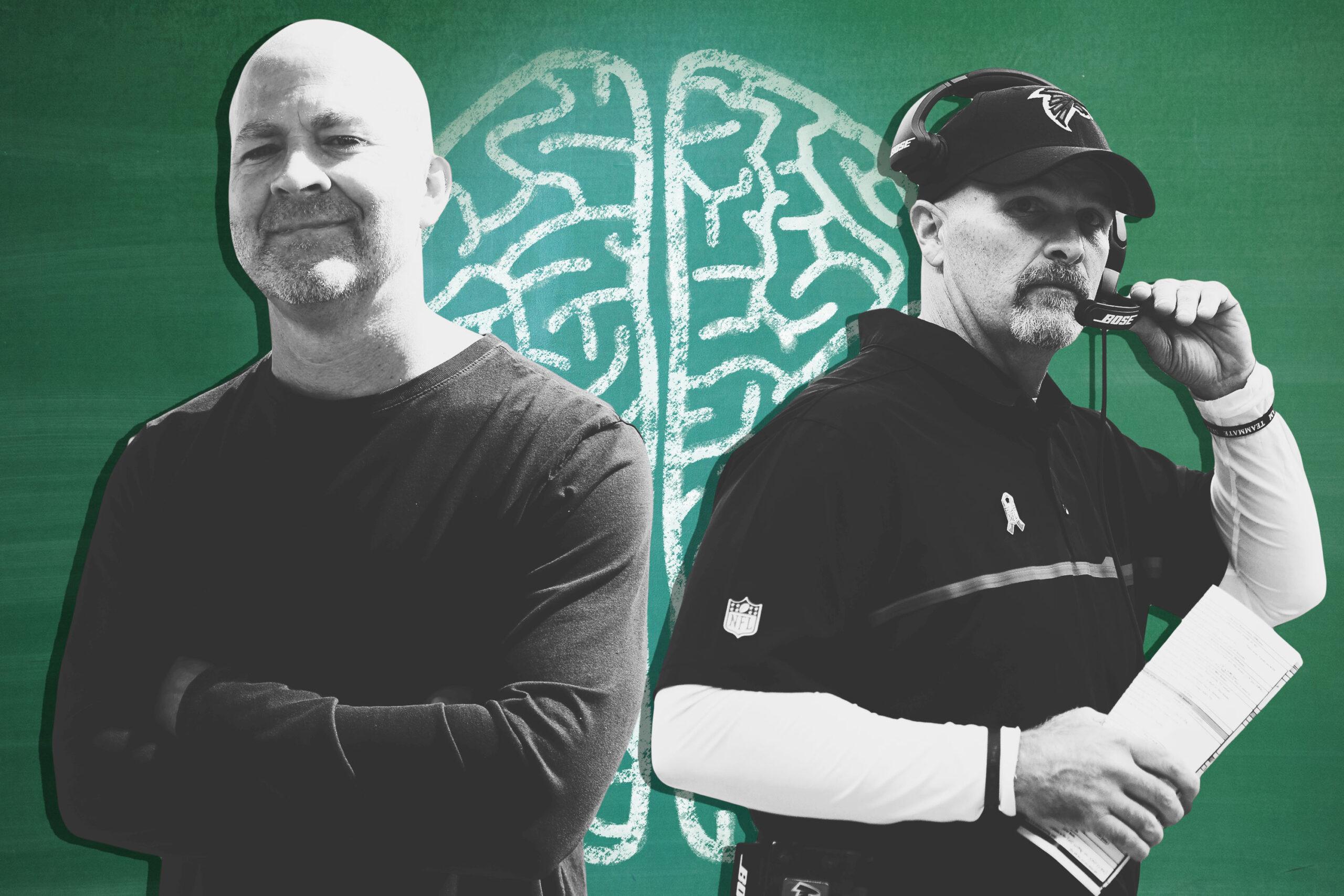

In their first years on the job, Shanahan and Colts general manager Chris Ballard have introduced Vision Pursue to their respective locker rooms, and Rausch’s program has become a fixture of what Falcons head coach Dan Quinn has built in Atlanta. Mindfulness exercises have become the NFL service du jour, and VP is the means through which some of the league’s best minds are enhancing their thinking.

“[I was] always looking for something else,” Quinn says of his career path from assistant to coordinator to head coach. “It’ll be better when … Now, I don’t think in those terms. It’s more the culture of what we’re doing and staying in the moment for everybody and creating that environment and culture for them. I knew when I came to Atlanta, I was the one responsible for creating that culture and adhering to it.”

Quinn’s introduction to Rausch is one of the many chance encounters that has allowed Vision Pursue and its philosophy to spread throughout sports. After serving a two-year stint as the defensive coordinator at the University of Florida, Quinn took the same position with the Seahawks before the 2013 season, overseeing a unit that would go on to win the Super Bowl.

The spring after Seattle’s triumph, Carroll came to Quinn with an assignment. “He kind of challenged me,” Quinn says. “Could I be more mindful, have better awareness for all sorts of topics—player-wise, [play] call–wise?” Not long after Carroll issued that request, Quinn got a call from his older sister, Maribeth, who thought he might be interested in a program that a former colleague had just started. That coworker happened to be Rausch. “[Dan] was buying into all the stuff Pete was doing, but he didn’t know how to get better at it,” Rausch says. “He loved that we had a website, a structure, a process.”

Quinn also loved that Vision Pursue had natural football ties. Jon McGraw, a 10-year NFL veteran who spent the final five years of his career with the Chiefs, cofounded the company with Rausch shortly after the two met at a charity event in 2013. By the time they connected, it had been about 18 months since McGraw’s retirement, and the former safety was deep into digging through the work of thinkers like Eckhart Tolle, who stressed the importance of existing in the present moment.

McGraw’s injury-plagued career had been colored by dissatisfaction similar to what Rausch had experienced in the trading world. “A lot of my career, I didn’t get to enjoy, even though I was living my dream,” McGraw says. “There were a lot of times where I convinced myself that it was probably better than it was.” In the days leading up to a game, McGraw would be hampered by performance anxiety, manifesting in what he describes as narcissistic tendencies that damaged his relationships with teammates, family members, and everyone in his vicinity. Combined with his tendency to replay key moments and sequences over in his mind, McGraw never felt able to exhale. “I was taxing myself unnecessarily all the time, and didn’t realize the cost of that,” McGraw says.

A lot of my career, I didn’t get to enjoy, even though I was living my dream. There were a lot of times where I convinced myself that it was probably better than it was.Jon McGraw, former Kansas City Chiefs safety and Vision Pursue cofounder

With the formation of Vision Pursue, McGraw and Rausch tried to create a shared language structured around the work of Haanel, Tolle, and others. One of their litmus tests came when they visited Ian Connole, the director of sport psychology at Kansas State. Connole, who holds a Ph.D. in sport and exercise psychology from West Virginia University, was understandably skeptical when two men unversed in his area of expertise claimed to have devised a new way to aid athletes and coaches. “To be honest, I was pretty hesitant,” Connole says. “I was like, ‘Who are these guys that don’t have a sport psych background that do something that sounds a lot like I do?’”

The enterprise had the feel of a traveling doctor riding through town with a miracle elixir. But when Connole heard the pitch, he grasped how VP’s approach could be intertwined with his own work. “The more I started talking to them about what they were looking to do and their philosophy, the more I realized that it was completely compatible with what I did,” Connole says. “I didn’t feel like they were trying to do something that was necessarily out of their realm.”

It was only a few months after Rausch and McGraw got Cannole’s stamp of approval that they approached Quinn with the product. Entering what would be his final season with the Seahawks, the coach had begun to change his attitude toward the job, even before he fulfilled his lifelong dream of landing an NFL head-coach position. “You start building a connection with players and coaches,” Quinn says. “And when you’re enjoying what you do and engage with the players and the coaches more, it made that whole experience that much better and stronger.”

Part of Quinn’s motivation to bring mindfulness training to the Falcons came from how central the practices had become to his own life. At home with his family, he has moments when he feels his mind start to wander. Those are often the stretches when he hasn’t looked at VP’s app in a few days—when the myriad demands for an NFL head coach accumulate. “There are lots of distractions that can come up for me,” Quinn says. “Sometimes overly focusing on the distractions, or thinking about the past or things way ahead in the future, those are things that can jam you up.”

Before mindfulness training made its way to the NFL, it was buzzworthy in the business world. And long before Quinn invited Rausch and McGraw to speak to his roster in Atlanta, the pair honed their approach while pitching corporations. Their first presentation was to Rausch’s former coworkers at Trading Technologies, and their interplay was rocky. “It was Russ kind of guiding through the PowerPoint and me adding color,” McGraw says. “He was the play-by-play, and I was the analyst. Let’s just say they didn’t have us back.”

The delivery is smoother these days, and hearing Rausch give his pitch, it’s clear how many times he’s laid out these talking points. Vision Pursue’s meetings typically open with a video of Kobe Bryant talking to Ahmad Rashad about learning the importance of mindfulness from Phil Jackson. “He’s one of my favorite athletes,” Falcons safety Ricardo Allen says of Bryant. “I’m like, ‘For sure, I’m doing this. I need this.’”

After citing other examples of how this type of thinking has disseminated across sports, Rausch asks whether players have trouble sleeping, whether they struggle to focus in team meetings, and whether they have a difficult time feeling present. “Most people don’t realize everybody is experiencing this,” Rausch says. “They think there’s something wrong with them. They don’t think there’s anything they can do about it. They try to sleep more or stop worrying. None of that helps.”

One of the pillars of this training gets at the reason Rausch started Vision Pursue in the first place. Most people, Rausch explains, don’t abide by an “expanding A” view of the world, meaning they derive their sense of self-worth from their accomplishments, leading to an existence in which they can never truly be satisfied. According to this rationale, any person driven by the rewards that come with moving from Point A to Point B is bound to be unhappy because Point B is always changing, whereas the focus should be on getting all that’s possible from an expanding Point A. Quinn says this problem describes him in a nutshell. “I was always this person that was looking to the next and the next,” he says. “Sometimes, I think I missed out on the present moment, on the experiences I had and the jobs I had that were so much fun.”

“‘Don’t listen to the tone. Dig into the information.’ When you start to do that, it changes everything.”

—Ricardo Allen, Atlanta Falcons safety

Another pillar of this program is attempting to understand the idea of the “automatic brain,” or the notion that people are wired to react to stimuli in different ways as a means of self-preservation. The key is to understand why a particular reaction occurs, rather than succumbing to the emotion brought on by any given situation. “I thought it was really hard to change the way you thought all the time,” Allen says. “I was like, ‘Man, I’ve been thinking like this for years and years.’ My auto-thought always popped on.”

Allen points to how mindfulness helped him late in the 2016 season, when the Falcons were barreling toward the playoffs and had spent nearly seven straight months around each other. Atlanta’s defensive backs coach (and now defensive coordinator) Marquand Manuel would harp on his players in the secondary, and his delivery can sound harsh. By the time the postseason arrived, Allen felt as if Manuel’s criticism had begun to mount. “At the end of the season, you remember all the critiques that your coaches have for you,” Allen says. “There’s a whole year, and everything you once messed up on or once did wrong, you have all that stuff bundled up in your lockbox of critiques. Then I ended up reading a passage [on VP] that said, ‘Don’t listen to the tone. Dig into the information.’ When you start to do that, it changes everything.”

For the Falcons and others, the biggest benefits of embracing mindfulness have little to do with football. Before taking over as the Colts GM in January 2017, Chris Ballard spent four years in the Chiefs’ front office. He lived a stone’s throw from McGraw, and their sons became fast friends. In one of their first conversations, Ballard, unprompted, brought up his love of Tolle’s work. “I was like, ‘OK, wow, we’re on the same page,’” McGraw says. “‘Because his books kind of changed my life two years ago.’” After McGraw introduced Ballard to VP’s program, he and his wife began using it regularly. “And it really helped me sift through a lot of stuff when I first walked in the door [in Indianapolis],” Ballard says. “We had this big task at hand—and we still do—but it was just about going day by day. Not worrying about a month from now, where we were gonna be.”

The most tangible results for Ballard come on his drives into work. One of daily meditation features in VP’s app is designed to make commuting more enjoyable; users are instructed to appreciate the shapes and colors of other cars, and to pay attention to the surrounding environment. While this may sound absurd in theory, both Ballard and Allen swear by its effects. “My first month on the job, I had no idea how to get to work,” Ballard says. “In the mornings, that’s when I most shut it off and paid attention to the drive—the scenery around me, everything you’d usually not notice.”

Falcons center Alex Mack also testifies to feeling the impact of these teachings, as there’s also a focus on not letting the inevitability of traffic affect your mood. “When you’re driving downtown at 5 o’clock, there’s going to be traffic,” Mack says. “You shouldn’t be surprised by that. That shouldn’t ruin your day.” In mindfulness parlance, that’s referred to as “expecting the expected,” an expression Quinn has worked into his everyday coaching lingo. “I talk in bumper stickers a lot,” he says.

Melding those simple mindfulness phrases with his message has made it easier for Quinn to sell related principles to his players, and in that respect he’s not alone. Encouraging players to embrace the process and live in the moment isn’t a new idea. Bill Belichick’s “do your job” decree falls under that umbrella; Nick Saban’s Process is renowned far beyond the University of Alabama; and Ballard says Andy Reid’s general demeanor creates that type of environment naturally. What’s attracted people like Ballard and Shanahan, who are in the early stages of of culture-building within their franchises, to VP is the systematic way these philosophies can be taught.

Shanahan says that even with all the time that players spend working on their bodies and breaking down the specifics of given schemes “there’s a lot of other stuff that goes with [being in the NFL]—playing under pressure, being able to control your anxiety, things like that. Everybody tries to find ways to do it, like meditating and being able to relax. That sounds great and stuff, but it can be hard for some people.”

Even with a tool like VP at their disposal, Mack and Quinn say they’ve struggled with some of the lessons. The universe of professional football is filled with restless, goal-driven personalities, which makes many areas of mindfulness training foreign. “Meditations I find the hardest,” Mack says. “Taking 10 minutes to calmly sit there, that I find the most difficult.”

Specializing the training is one of the many ways that Quinn and others have tried to make engagement with the ideas easier, but Ballard concedes that the work it takes to make the approach a natural part of players’ lives never really ends. “[Players] hold onto that worry,” Ballard says. “Players worry about, ‘OK, this is how I performed.’ Instead of letting go of the past and staying in the present moment, they worry about all the bad things that happened. Now your mind is playing tricks on you.”

By the fall of 2016, Vision Pursue had three regular football clients: the Falcons, the Kansas State Wildcats, and the high school team in Rausch’s hometown of Barrington, Illinois. While Barrington’s head coach, Joe Sanchez, may not know the challenges associated with presenting these concepts to rooms full of adult millionaires or scholarship athletes, he still faces many of the same obstacles teaching mindfulness to his roster. “It’s still a hard concept,” Sanchez says. “And when I say that, it’s kind of one of those concepts that’s hard to believe in right away because of our natural, default mind-set. We want to naturally resist it because we’ve grown up in [a certain manner] and been trained that things are supposed to look a certain way.”

Some people might think using meditation and having a mental performance side might soften you up, but it’s just the opposite. It allows you to experience yourself the way you’d like to be.Dan Quinn

Pushing past the power of people’s ingrained habits is the first barrier Rausch, McGraw, and others have had to overcome in introducing anyone to this school of thinking, but in the NFL, that is compounded by the sport’s culture. “Some people might think using meditation and having a mental performance side might soften you up, but it’s just the opposite,” Quinn says. “It allows you to experience yourself the way you’d like to be. We think of ourselves as a tough-ass, hard-nosed team. But when we have a chance to apply some of this mental training, it helps with football, but it also helps off the field quite a bit too.”

Quinn’s adherence to mindfulness training seems more fortuitous now than ever. The 2017 Falcons face a mental hurdle unlike any in recent league memory. Blowing a 28-3 lead in Super Bowl LI could have delivered a blow so crushing that it lingered with the team into the subsequent season. But after years of training himself to avoid living in the past and future (and doing all he could to teach his players the same), Quinn seems ideally suited to help the Falcons navigate the aftermath.

“In [the media], it’s so much of ‘Are you guys going to get back to the Super Bowl?’” Quinn says. “Honestly, we’re so far from thinking that. I’m not even to the spot where we talk about our own division that much. To play really well in our division, you better be on your game. Getting back at the Super Bowl isn’t where are minds are at.”