Ask the Maester: How Many Night Kings Have There Been?

Plus: Has winter reached all of Westeros? And who was the Night King before he turned to ice?

Rest in power, Viserion. You deserved better.

Why the Night King threw his ice javelin at you, in the air, rather than Drogon, who was on the ground and carrying the queen, is probably best explained by: reasons. Sure, spiking Drogon would’ve stranded most of the good guys in the show and ended the war against humanity before it even started. But why take the layup when you can hit the half-court hesi jimbo? Shooters shoot.

On to your questions from “Beyond the Wall.”

Jordan asks, “During the last Long Night thousands of years ago, when the children of the forest banded together with man to defeat the White Walkers, did they kill the Night King? Is this the same Night King from that Long Night, or a different one?”

Great question! The Long Night is one of the great mysteries of this story, precisely because it was so important and happened such a long, long time ago. George R.R. Martin is a history buff in the truest sense. He has a keen interest in the way people and places are shaped by events, even those that have receded so far into the mists of time that only their broadest outlines are known. A large part of what makes the books and show feel so rich is the sheer depth of the world’s shared history. Whether or not George ever finishes the books (COME ON, MAN; DON’T LEAVE IT LIKE THIS), his world-building achievement will stand on its own as one of the most fully realized fictional spaces in literature.

The Long Night, terrifying as it was, is a wonderful example of this. There are countless others: The (happily brief) demise of House Stark at the hands of the Boltons takes on an air of tragic but foreseeable destiny when you understand the centuries of open enmity between the two families. Tywin, Tyrion, and Cersei Lannister are just the latest apples under the mighty bower of the house’s progenitor, the legendary Lann the Clever, who, thousands of years ago, winkled the Casterlys out of their ancestral home without so much as unsheathing a butter knife. King’s Landing is so named because it’s the place where Aegon the Conqueror made landfall over 300 years ago. House Manderly of White Harbor in the North can trace its roots to the banks of the Mander River in the Reach. And the dilapidated state of the Night’s Watch—a tattered collection of criminals and otherwise ruined men inhabiting a few ruined castles along the Wall on the frozen and forgotten edge of the world—is heartbreaking when contrasted with the order’s truly heroic origins. Once, long ago, the warriors who founded the Watch saved the world.

But how? We don’t exactly know. Myths, legends, and prophecies are the best road maps we have. There’s the legend of Azor Ahai, the messianic hero who, after many tries, forged the fiery blade Lightbringer by stabbing his wife in the heart with it. There’s the prince that was promised prophecy, which tells of a hero born amid salt and smoke under a bleeding star. The Azor tale originates in the far east of Essos; the prince is of unknown origin. Both are obviously steeped in metaphors. Each speaks amorphously of a darkness that needs to be vanquished. We assume this refers to the Long Night, but that isn’t explicitly stated.

In the North, folktales speak to the Last Hero and his unambiguous struggle to defeat the White Walkers. This is likely the most historically accurate telling of the Long Night, the tale having been passed down in a direct line, from generation to generation, and originating all the way back to those who were there. This makes sense since the First Men of the North were on the front lines of the battle. By the time of the Last Hero’s emergence, the Long Night had gripped the world in darkness for years; perhaps decades. There were people alive then whose entire life experience was that of an unyielding cold and gloom, starvation, death, and monsters that hunted in the dark.

In desperation, the Last Hero—along with his human companions, plus a horse, a dog, and a sword—set off into eternal night to seek the aid of the Children of the Forest. The search apparently lasted years. Along the way, all of the Hero’s friends died or abandoned him. His horse died. His dog died. Finally, even his sword shattered in the merciless cold. But the Hero reached the Children. With their help, the Night’s Watch formed, and the Battle for the Dawn was won. The surviving White Walkers fled to the Lands of Always Winter, where they apparently slumbered, forgotten and unwatched, free to gather their strength, for the next six to eight thousand years.

Javan asks, “Where the hell is winter? The gloomy Starks are always sure to say that ‘winter is coming.’ But winter officially came months ago, if not a year ago, (white raven) and it seems to be no big deal. It isn't even constantly snowing in Winterfell! Varys got a tan for goodness’ sakes!”

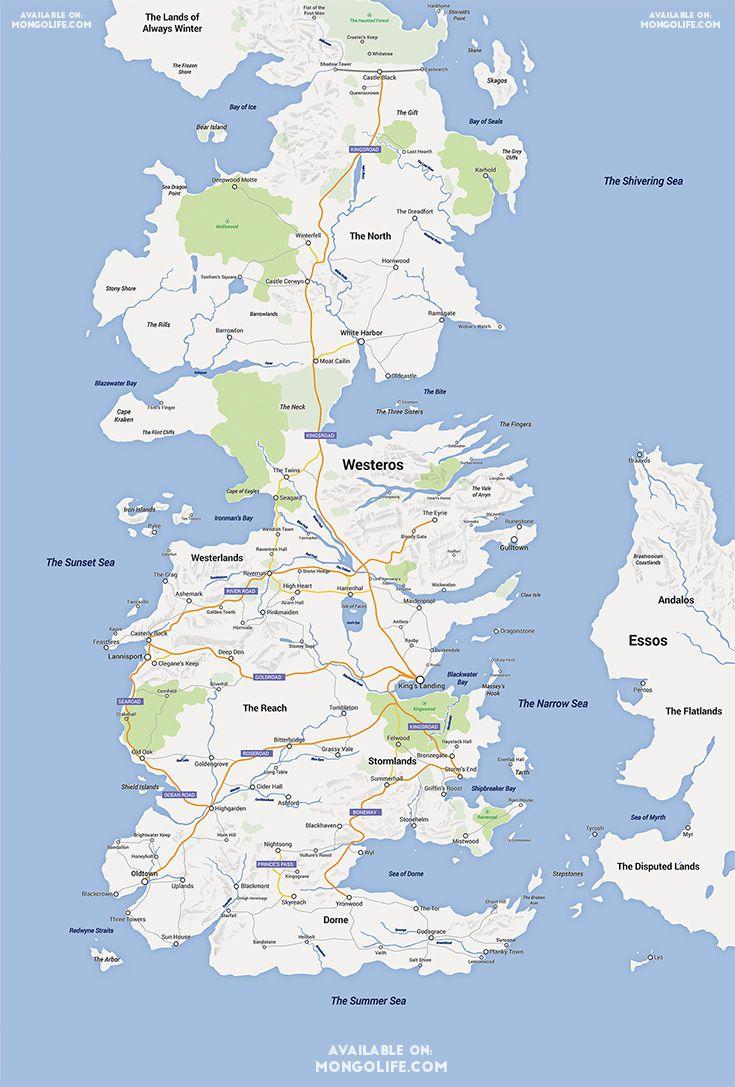

Winter is here but, just like in real life, that doesn’t mean that it snows every day! Look, despite the contracting effects of the incredible travel speeds we see every episode, it’s important to remember that Westeros is freaking huge. When first asked about the size of the continent, Martin, wisely, was cagey about his creation. Eventually, he revealed that he intended Westeros to be roughly the size of South America. Pretty big, guys!

Early this season, when Arya briefly reunites with Nymeria in the Riverlands, after leaving the Twins littered with dead Freys, we see that snows are already falling there. The former seat of House Frey is just south of the Neck, the swampy borderland that guards the North. King’s Landing is perhaps 800 miles to the south. (I’m using the map length of the Wall, known to be 300 miles, as a rough scale.) Or a bit more than the distance from New York City to Charleston, South Carolina. No surprise, then, that in the South, winter is still coming.

A related and commonly asked question: Does winter in Westeros affect the entire world? The historical record suggests yes! The people of Yi Ti, on the eastern edge of the known world, tell of a time when the sun “hid its face from the earth for a lifetime.” It was a woman with “a monkey’s tail” who, somehow, halted the catastrophe. (Why hasn’t this myth caught on?!) Remnants of the Rhoynar culture of central Essos allude to a darkness that caused the waters of the Rhoyne River to freeze and dwindle. Rhoynish folklore says that it took the magical creatures of the river uniting in song—the Crab King and the Old Man of the River are specifically mentioned—to bring back the light. (Actually, this is kind of what’s happening!)

Personal theory: Winter begins in the Lands of Always Winter and spreads progressively outward. Thus a winter of long enough duration should affect the whole world.

Michael asks, “What do we know about the Night King’s identity? Do you subscribe to the theory that he’s Bran or maybe another Stark?”

I don’t think he’s Bran. The guy the Children of the Forest turned back in Season 6 had blond hair and looked nothing like Bran. Furthermore, I think making Bran the Night King would be objectively dumb. That said, the show’s been so wildly unpredictable about its decisions. Clearly, the showrunners have changed the makeup/CGI profile of the Night King, not to mention the actor who plays him, and the results are that he looks more like Bran.

I do, however, think he’s a Stark. In the books, all the records pertaining to the Night’s King—the evil 13th Lord Commander of the Night’s Watch, who, along with his corpse bride, carved out a kingdom for himself along the Wall—were purged after his defeat by the combined forces of the Stark King of Winter and Joramun the King-Beyond-the-Wall. Only the Starks would have the juice and motive to “obliterate” the Night’s King’s name “from history.”

Now, the book and show versions of the Night King might be totally unrelated. But if the Night King is a Stark, knowing the family’s well-established talent for warging and greenseeing, this, perhaps, helps explain the source of the King of the Dead’s power. It could be that he’s simply a powerful warg whose power allows him to control the dead.

Thiago asks, “Is the Night King capable of turning every corpse available in the Seven Kingdoms into wights? For instance, could he turn the freshest bodies in the crypts of Winterfell?”

Yes.

Tyler asks, “Which is more believable: Tormund suggesting Jon bend the knee, or Jon giving up the sword he that has KILLED A WHITE WALKER WITH?”

Jon offering Longclaw, the ancestral sword of House Mormont, to Jorah, son of Jeor, actually makes a lot of sense. That’s exactly what Jon would do. He’s an honorable guy who prizes familial bonds precisely because he was raised a bastard. What’s strange is that he didn’t do it sooner or mention it to Lyanna Mormont, current head of Bear Island.

As for Tormund suggesting Jon kneel … yeah … that was weird.

Jordan asks, “Ice dragon? … Tell me about this.”

Ice dragons proper—distinct from a dead dragon turned wight—are legendary creatures. They are mentioned in the text enough times that there must be some truth to the tale. The histories speak of ice dragons roaming the skies above the Shivering Sea. Like the White Walkers, ice dragons are said to be made of living ice, with glowing “eyes of pale blue crystal.” They breathe blasts of freezing cold instead of fire and “can freeze a man solid in half a heartbeat.” No concrete evidence of their existence—bones, scales, and so on—has ever been found because the creatures apparently have a convenient habit of melting once they die. Many sailors over the centuries have claimed to have spied the creatures.

In the books, Jon recalls how Old Nan (who has yet to be proved wrong about a single thing!) told him stories about ice dragons.

Can a deceased dragon breath arctic-cold blasts of air? We’ll soon find out.

Emma asks, “Hasn't Jon just spent the past however long on Dragonstone digging up Dragonglass? Why did he not take any of that with him beyond the Wall?”

They brought it! That’s what the Sledshirts were presumably dragging on the sled.

Matt asks, “Why can't Jon think to offer a probationary alliance before jumping straight into the bending of the knee?”

I’m fine with Jon bending the knee. It’s just strange that none of Dany’s or Jon’s advisers have suggested marriage as a straight-line solution to the issue of who swears fealty to whom. The match makes sense. Jon rules the largest region of the Seven Kingdoms. As Ned Stark’s son (as far as anyone except Bran knows), his bloodline reaches back to the very dawn of history. He commands an army, according to Sansa, 20,000 strong. And he and his troops know how to fight in winter. Sure, they’re related; Dany is Jon’s aunt. But they’re unaware of it and, anyway, that kind of match is very on-brand for the Targaryens, who regularly married their siblings.

Matthew asks, “Is there a chance Arya uses a face to trick Littlefinger (via non-dead face swap) into a mistake, or are we heading toward a Sansa-finally-getting-blood-on-her-hands scenario via Valryian dagger?”

The Winterfell plot is wild. I really could not tell you what’s going on there or what anyone’s motivation is. Sansa being concerned about the letter she was forced to write while she was a young teenager and being held hostage in King’s Landing makes very little sense. Cersei, Littlefinger, Varys, and Pycelle were in the room when Cersei dictated that letter. Robb read it aloud to Maester Luwin and Theon. Luwin noted that the message was in “your sister’s hand, but the queen’s words.” Right after reading the letter, which demanded that he come south to swear fealty to Joffrey, Robb called the Stark banners.

The idea that this letter is not widely known is crazy. Firstly, several people witnessed Cersei threaten Sansa, and Robb surely would have mentioned it to his bannermen as a way to sell the justice of his cause. See what they’re forcing my sister to do?! Secondly, and just as importantly, people in this world are well experienced in the concept and practice of political hostage-taking. This is not some alien idea. No one would hold Sansa, who, again, was barely a teen, responsible for the words that she was forced to write while being held by the family that beheaded her father.

OK. With that out of the way, there is no evidence anywhere that Faceless Men can steal faces from a living subject. The “non-dead face swap” is not a thing. That doesn’t mean that the show won’t make it a thing. The scene in which Littlefinger tries to convince Sansa to use Brienne against Arya is strange. There’s none of the usual Littlefinger reaction shots, and he doesn’t say anything particularly insightful or, interestingly, anything that Arya wouldn’t know. It’s almost as if the show is trying to set up the suspicion that Arya is posing as Littlefinger in an attempt to get her to admit to betraying—or wanting to betray—Jon. And when Sansa (foolishly!) sends Brienne south, under this reading of the scene that would mean she “passed” Arya’s test, thus allowing the sisters to team up and take down Littlefinger. Again, there is no indication that “non-dead face swapping” is possible. But, man, weird scene.

Thanks, and see you next week!

Disclosure: HBO is an initial investor in The Ringer.