If there’s a moral to the story of this baseball season, it might be that the loss of one player can’t kill a campaign. We’ve had ample opportunities to learn and relearn that lesson this year, as team after team has held up or flourished despite the absence of a star.

From late May to mid-July, the Angels were missing Mike Trout, who was off to the best-ever start to a season in the best-ever start to a career. Somehow, they hit just as well and won just as often without him as they had before he got hurt. The Dodgers were 67-31 (a .684 winning percentage) when they lost Clayton Kershaw, the best pitcher of his generation, last month. They’ve gone 23-7 (.767) since. When the MVP-pacing Freddie Freeman fractured his wrist in mid-May, the 16-21 Braves acquired Matt Adams and cash from the Cardinals for a no-name minor leaguer. (Fine, that’s not nice—his name is Juan Yepez.) Adams posted a Freeman-esque .285/.333/.589 slash line with 12 dingers in 165 plate appearances while Freeman was out, and the Braves went 24-20. At least the Astros have had the decency to play worse without Carlos Correa, although they’re still sitting on a 13-game division lead—as are the Nationals, who’ve lost a load of top-tier talent and nonetheless remain on pace to tie a franchise record for wins.

The corollary to the “loss of one player can’t kill a campaign” maxim would seem to be that the addition of one player—or, for that matter, a preexisting player’s unparalleled hot streak—can’t make a campaign. In most cases, there’s truth to that, too. But we may have to make an exception for the Marlins’ Giancarlo Stanton.

Perhaps in response to a career-worst, whiff-tastic slump late last spring, Stanton morphed into a more contact-oriented and less powerful hitter from the middle of last season through the first two months of this year. In retrospect, that version of Stanton seems to have been an intermediate stage in a larger evolution. In recent months, he’s made a mechanical adjustment, closing off his stance and taking more controlled swings in a way that’s allowed him to keep making contact and resume hitting home runs, all while staying healthy for the first time in years. In short, he’s become the best of both Stantons.

Although the 27-year-old Stanton is still capable of hitting home runs we can gape at—since mid-July, he’s launched the seventh- and ninth-longest homers of the season—his average dinger distance is lower than it’s been since before the juiced ball, and he no longer squats at the top of the exit-velocity leaderboards. He does, however, lead the season’s second-most-prolific home run hitter, Aaron Judge, by 13 bombs. No home run king has finished a season with a lead that large since Willie Mays in 1965, whose 52 big flies blew away his teammate Willie McCovey’s 39. (Jimmie Foxx, whose 48 homers in 1933 led Babe Ruth by 14, is the last to finish with a lead larger than 13.) To make matters more improbable, Stanton is doing this during an era when home runs have been distributed democratically, probably because a bouncier, better-carrying ball has acted as an equalizer, disproportionately boosting weaker hitters who otherwise would have only warning-track power. (Stanton has the majors’ most no-doubt homers, but he also has the second most that just scraped over the fence.)

On Sunday, Stanton became the first slugger since Chris Davis in 2013 to reach the 50-homer mark, and the first NL player to do so in a decade. Stanton’s game-winning milestone moon shot, which snapped a 2-2 eighth-inning tie, brought his August total to 17, one short of the 80-year-old home run record for the month. That comes on the heels of an almost-as-scary July, in which he hit 12. Go back to the beginning of his most torrid stretch, which began with a two-dinger day on July 5, and the stats say that he slashed .353/.461/.935(!) with 29 dingers over a span of 204 plate appearances before the Nationals held him hitless in three at-bats on Monday.

That’s one hell of a hot streak. In fact, we can quantify exactly how hot it was. Using a tool built by Rob McQuown of Baseball Prospectus—which I’ve previously used to examine shorter stretches of blistering performance by Bryce Harper in 2015 and Gary Sánchez last season—we can compare Stanton’s production during that span to all previous spans of the same length within a single season since 1950. If 204 plate appearances sounds like an inelegant, not-round-enough number, just pretend it’s 200. We’re cherry-picking a particularly hot stretch for Stanton, of course, but that’s the point: We want to see how his hottest streak stacks up. Nor are we cooking the books in his favor, because we’re comparing only to other streaks of the same number of plate appearances.

The hot-streak query, which assesses each eligible streak’s True Average (TAv), a BP all-in-one offensive stat that adjusts for era and park, reveals that Stanton’s was the 332nd-hottest hot streak of that length since 1950. Maybe “332nd” doesn’t sound like much, but consider that Stanton’s hottest streak of 204 plate appearances—from his 347th through his 550th PAs of this year—is being compared to millions of previous streaks of 204 plate appearances. It’s extraordinarily difficult to come anywhere close to the top of that list.

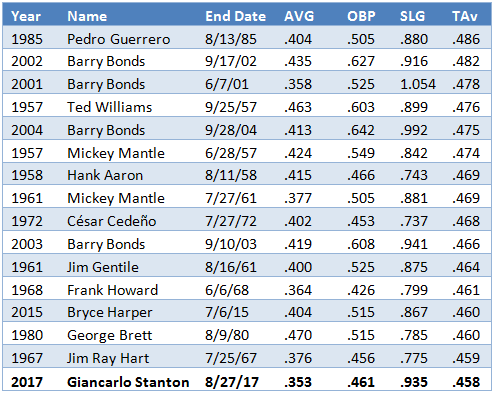

Most of the 331 entries ahead of Stanton belong to overlapping streaks; Stanton himself places six overlapping streaks from this season in the all-time top 1,000 (including PAs 345 through 548, 346 through 549, and so on). If we remove the duplicate entries from the same hitters in the same seasons, we’re left with only 15 stretches hotter than Stanton’s, most of which belong to players with Hall of Fame–caliber careers.

Barry Bonds and Mickey Mantle make the list in multiple seasons; after accounting for that, we can say that only 11 hitters since 1950 have ever been as hot for as long as Stanton just was. As the table above indicates, Stanton’s slugging percentage over his hottest streak tops that of any of the non-Bonds streaks ahead of him. His streak doesn’t rank even higher largely because it featured a relatively “low” batting average and on-base percentage, and also because he’s put on this power display during the highest home-run-rate season in history.

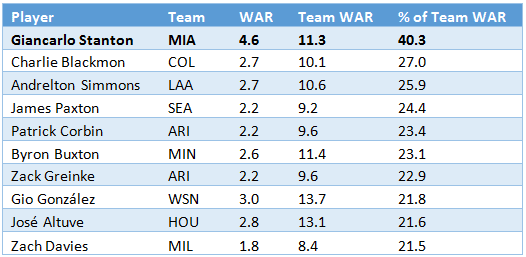

As one would expect, Stanton’s win probability added and WAR during that 204-PA period from July 5 through August 27 dwarfed those of his closest competitors.

After a losing April and May, the Marlins began to bounce back in June, but their record still stood at just 37-45 before Stanton’s hottest stretch started. While he was streaking, they went 29-18. Stanton hasn’t had a ton of help. Over the same stretch, the closest Marlin on the WPA list was Marcell Ozuna, with 1.3; the second-highest on the WAR list was Christian Yelich, with 1.9. Those two and Derek Dietrich have supplied most of Miami’s non-Stanton offense this month, and some solid work from the back of the bullpen (in relief of an injury-racked and not-good-to-begin-with rotation) rounds out the bright spots.

That brings us back to the contention that Stanton has carried his team. And to the extent that the structure of baseball permits, the numbers bear it out. During his July 5–August 27 hot streak, which not-so-coincidentally occurred in the midst of a winning close-to-two-months for the Marlins, the percentage of team WAR that Stanton produced easily outstripped that of any player on a team with a seasonal record of .500 or better. By roster spots occupied, Stanton was one-twenty-fifth of the Marlins. WAR-wise, he was more like two-fifths.

Even after all of his heroics, the reigning NL Player of the Week (and presumable Player of the Month to be) almost certainly won’t set a new home run record. And even with one of the weakest rest-of-season schedules, the Marlins probably won’t make the playoffs. (After their loss on Monday, their odds of winning a wild card sit at 13.6 percent.) But just reaching a point where we would bother to speculate about either of those outcomes required an incredible binge of hot hitting. The Stanton we always hoped we would see has arrived, just when we were ready to stop searching.

Thanks to Rob McQuown of Baseball Prospectus and Dan Hirsch of The Baseball Gauge for research assistance.