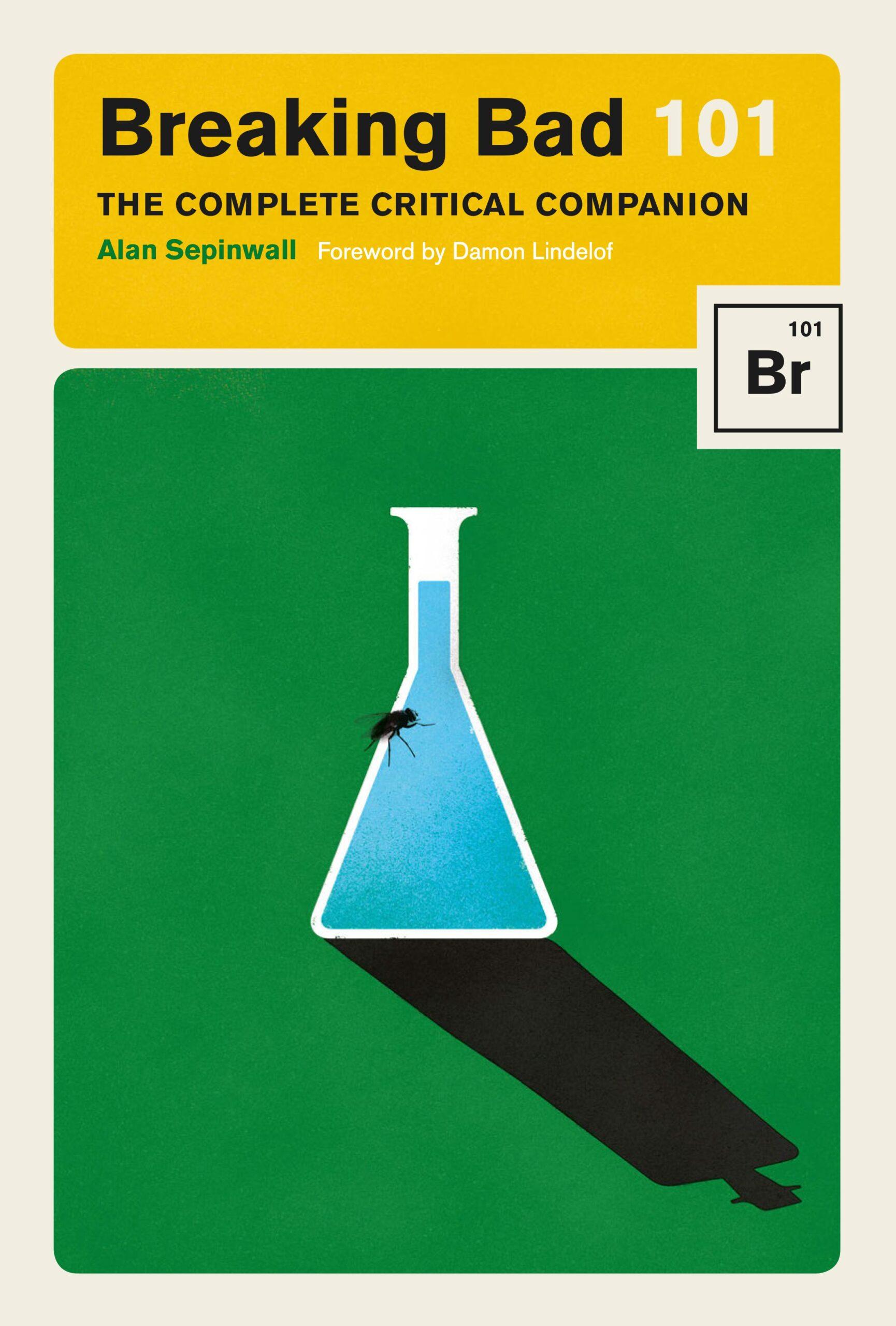

On October 10, Abrams Books will release Breaking Bad 101: The Complete Critical Companion, featuring reviews of every episode of the series by Uproxx TV critic Alan Sepinwall. Some are roughly what Sepinwall wrote when the episodes originally aired, some have been heavily rewritten, and some—like this essay on the narrative sleight of hand behind “Face Off,” one of the most famous Breaking Bad episodes of all—were written from scratch, either because his opinion changed or because it needed more context away from the weekly recap grind.

Lilies of the Valley

Skyler: “Was this you? What happened?”

Walt: “I won.”

“Face Off” documents Walter White’s greatest victory, and perhaps Breaking Bad’s as well. Never before has Walt overcome such enormous odds, nor taken down so formidable a foe, as when he orders the explosive death of Gustavo Fring. And as a piece of suspense, with a cathartic release (the final shot of Gus revealing that the episode’s title is meant to be taken literally) before a stomach-churning closing revelation, “Face Off” is the summation of nearly every narrative and stylistic lesson the series has learned over its four seasons.

But before we celebrate either victory, as Walt so obviously feels he deserves, we have to ask ourselves two questions:

1. Do we believe Walter White would poison a child to pull off this plan?

2. Do we think it was fair of Breaking Bad to keep that part of the plan hidden from us until after it was done?

The answer to the first question is sadly, but perhaps not surprisingly, “yes.” Once, Walt would have recoiled at the idea of in any way risking the life of an innocent boy to further his own ends, even if he felt confident that the lily of the valley berries would hurt Brock but not kill him. That’s the Walt that emerges in “Fly” (S3E10): the Walt who recognized that he had lived for too damn long and was likely to only hurt people going forward. But any semblance of decency Walt had left died down in the crawl space (if he even still had it after he let Jane die), and has been replaced by a desperate, wounded animal called Heisenberg who will do anything to survive. The episode forecasts Walt’s extreme selfishness in the earlier scene where Walt sends his next-door neighbor Becky (played by Gail Gilligan, Vince Gilligan’s mother!) into his house, like a canary in a coal mine, just to flush out any goons Gus might have parked there. As with Brock, he’s relieved that she survives, but he still sent her in there in the first place, knowing full well that she could have stumbled across the killers and taken a bullet as a result. This is who Walt is: a guy who will use anything and anyone, innocent or guilty, to keep himself alive.

So, no, it’s not a stretch to think that Walt would cheat in this way—endangering Brock, lying to Jesse about it in order to win him back—to pull off what he perceives as his crowning triumph. But Breaking Bad presents Walt’s repugnant maneuver as a cheat of the narrative ethos the series has established since its first episode, albeit a cheat that may be necessary to accomplish the most shocking aspects of “Face Off.”

Though the series began as one primarily focused on Walt, it always had a third-person point of view. We followed Walt, but we also saw what his family, his partner, and his enemies were doing. The Cousins wandered around Albuquerque for half a season without Walt even learning of their existence, and if Season 4 didn’t show us everything Gus was planning, it showed us enough of each side of his war with Walt so that we could tell who had the advantage at any given moment. And even when we were in the dark on an enemy’s actions and motives, we always knew what Walt was doing and why. From the pilot through the early part of “End Times,” no steps were skipped, no big secrets kept from us (technically, we spend the first half of “Full Measure” [S3E13] unaware that Jesse is still in town and working in concert with Walt to turn the tables on Gus and Mike, but that’s a much smaller reveal in terms of what it means for Walt’s character development) when it came to the rise of Walter Hartwell White.

Until this one.

Walt is missing from “End Times” (S4E12) from the moment his spun revolver points itself at the plant to Jesse showing up at his door to confront him about Brock. We don’t know where he is, what he’s doing, or why he’s doing it. The concluding shot of “Face Off” makes clear that he used the lily of the valley to make the poison that put Brock in the hospital, confirming that Jesse’s original suspicions about Huell lifting the cigarette pack from his pocket and Walt poisoning Brock were wrong in its specifics, but correct in its generality. But we don’t know how he did it, or even that he did it, until long after the deed was already done. This is a show that devoted two of its first three episodes to proper corpse disposal methods. It’s a show that once had Walt challenge Jesse on such a basic criminal procedure as loading a revolver, and that lingered over each agonizing second as he elected not to save Jane’s life. This is a series that has shown time and again that it values these in-between moments, that it treasures not only the story but also every step it takes along the way. At every point before now, Breaking Bad has made clear that we understand exactly how Walt does everything that he does, and how far he’s fallen from the man we met in the pilot. We bear witness to everything—but not this.

How would “End Times” and “Face Off” play if we stayed with Walt after the revolver stopped spinning, watched him turn the berries into something Brock might eat or drink, arrange for Saul to have Huell pick Jesse’s pocket, then rehearse the lie over and over again until Jesse comes in to confront him? It would probably, in many ways, be unbearable: Walt’s most despicable act yet played out for us—and only us—to see, while poor Jesse is duped into realigning himself with the man he was completely justified in wanting to kill. Knowing this in real time would have made it awfully difficult to take any pleasure in seeing this Walter White plan come together, because we would have the horrible cost of it at the front of our minds throughout. No matter how deftly Gilligan assembles the rest of the plan—which involves Jesse pointing Walt to Hector Salamanca, who turns out to be ready, willing, and able to make himself, his wheelchair, and his trademark bell into the instruments of their mutual enemy’s destruction—the tragedy of Brock’s fate would seem too great.

It is arguably for this reason that Gilligan decides to keep the biggest leap forward on Walt’s path to complete monstrousness from his viewers until after Walt thinks he has won. Presenting it in this way might violate the show’s storytelling rules, but it also makes us complicit to Walt’s crime just after we might have been enjoying the spoils of his victory. Walt may be guilty, but then, Gilligan implies, so are we. Season 4 plays with our sympathies just as much as Season 2 did, only this time the fulcrum is between Walt and Gus rather than Walt and Jesse, and there are many times when it seems as if Gus is the one we should be rooting for. But when we think Gus poisoned Brock —when we are duped right along with Jesse—it grants us a kind of permission to fully root for Team Walt again, loudly and with less equivocation. Walt isn’t good, but a Gus who would poison a child to turn two enemies against each other is clearly evil, and in need of as much retribution as Walt can point at him.

When Gus realizes that Tio’s bell isn’t ringing because it’s become a trigger for the bomb Walt has strapped to the wheelchair, and when he reflexively straightens his tie even though half his face is gone and he’s seconds from death, it’s a grand triumph for Walt, and for all of us who have allowed themselves to cheer for him again ... which only makes the episode’s final shot all the crueler and more effective. (Precision to the last, and the best goodbye Gilligan could have given Giancarlo Esposito after the two had made Gus into the series’ greatest villain—other than Walt himself. A Gus who perishes instantly in the explosion still goes out in memorable fashion. But the Gus who staggers out of the room, framed in a way where we for a moment wonder if he has improbably survived all of this—if he really is the Terminator—before we see the extent of the damage and come to understand that he is so concerned about appearances that he uses his last moment to subtlety correct his tie, makes it a death for the ages.)

It had been many episodes since it was as easy to take Walt’s side as it feels in these two episodes; it is our relative sympathy for Walt that makes the revelation of his evil hit so much harder. We might cheer Gus’s death, and enjoy the sight of Walt and Jesse working together like a well-oiled machine as they arrange the fiery destruction of the super lab—a payoff that not only allows them to get revenge on their miserable time working there, but also to heal their season-long schism—and we might revel in that image of Walt on the top of the parking deck, master of all he surveys (especially the station wagon that Gustavo Fring will never get to drive home). With Gus dead, most of his enemies in the cartel eliminated, and Mike still recuperating south of the border, Walt has before him an uncontested road to finally becoming the kingpin he’s long fancied himself to be. If the coldness of the way he announces his victory to Skyler is startling (and terrifying to her), it also feels in keeping with the masterful maneuver he just pulled off. And this is when Vince Gilligan rips down the curtain and shows that Walt actually accomplished this trick at grave cost to whatever remains of his soul.

The misdirection works on us for the same reason it worked on Jesse: We want to believe, even after all that he’s done (even after the death of Jane, which we have knowledge of that Jesse lacks), that this is a line Walt would never even think of crossing. We have been conditioned to think this because he’s a father himself who is tender with Flynn and Holly, because we were introduced to him as a relatively normal man who fell into a life of crime without realizing its full implications, and because, frankly, he is the main character on the show we’ve been watching for four seasons. Even in the cable TV antihero universe that made Breaking Bad possible, it feels unthinkable for a protagonist to knowingly endanger a child in this way. Walter White, though, not only did it, but did it in such a nefarious and underhanded fashion that the only way to feel the full brunt of it is to find out about it right as we’re encouraged to dance at the victory party.

This is part of the savage cruelty of this moment, and of its genius. Yes, this narrative cheat justifies itself through its sheer effectiveness and makes us complicit in Walt’s undeniable corruption, but it also reveals something much deeper and perhaps more unsettling than Walt’s actions. By keeping this crucial information from us until the very end, “Face Off” violates the most basic narrative rules of Breaking Bad in order to show us that we may have gotten too comfortable with our protagonist. Up until now, we have spent almost every narratively essential moment with Walt. We spent hours with the man, and assumed we knew everything about him that we needed to know. In a single gut-punching shot, Vince Gilligan shows us just how wrong we were.