Paul Heyman spent the better part of his childhood watching his father charm a jury. A personal injury lawyer in the Bronx, Richard Simon Heyman was the loquacious type. He knew his audience and could stitch together a case from opening argument to closing remarks. Like many provocative counselors, he’d push and prod the judge until the bench punched back. “Your honor,” he would reply, “I’m just an advocate.”

Heyman often shadowed his dad at Bronx Criminal Court. When he was 7 or 8 years old, one of his father’s colleagues, a nonagenarian attorney named Schmuely, dropped dead while delivering his summation to the jury. Legend has it that his final words were, “I hereby rest my case.”

Later that day, father told son, “If I ever go that way, do not shed a tear for me. I am going out in style. Find something in life that fulfills you to that degree — even your worst days will be good days.”

On a recent fall evening, Heyman arrives at a steakhouse near Grand Central Terminal full of good cheer. He has the wide, assured gait of a man who sees all the angles. He always wears a suit in public, even during 3 a.m. runs to 7-Eleven, in the event that someone requests a selfie. Tonight he’s sporting a navy blue Pronto Uomo three-piece, relaxed blue Brioni tie, and light-blue Tom Ford shirt. A black fine-toothed comb peeks out of his vest pocket.

“How hungry are you?” he asks, settling into a corner booth.

Heyman speaks in the hyperbolic argot of marketers and promoters. After the restaurant’s owner greets us, Heyman tells me, “It’s his time. He’s on fire.” Minutes later, when asked about his own business, the advertising agency Looking 4 Larry, Heyman repeats the appraisal. “We’re just on fire, just on fire,” he says for emphasis, before listing their accounts, which include a microencapsulation startup on the West Coast and Cirque du Soleil in Times Square. “In terms of an agency, it’s just such a busy time. We can’t staff up fast enough.”

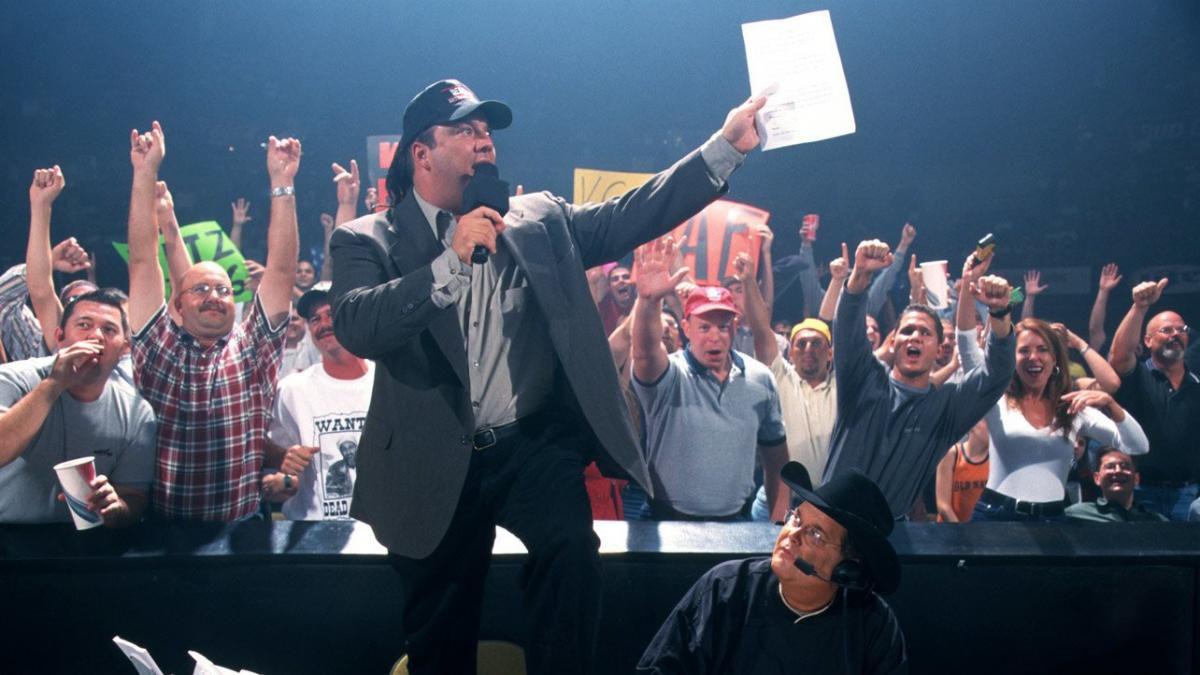

But it’s in the ring where Heyman’s candor and gift for outsized performance has been most celebrated. As the advocate for the hulking WWE Universal Champion Brock Lesnar — the self-appointed title “advocate” is a tribute to Heyman’s father — he’s transformed the routine of the wrestling promo into an art form. (Even when he’s interrupted by a wedding proposal.)

“When Paul made his speeches, you truly wanted to go to war for him. Every ECW wrestler was willing to die in battle for the company. I don’t mean that figuratively, but we were ready to do whatever it takes for the world to notice us.” — Former WWE star Bubba Ray Dudley

“He’s obviously the best talker in the industry right now,” says the legendary announcer Jim Ross. “When he is on his game, he is as good as there ever has been at establishing a point and supporting it. Paul probably would’ve been a hell of a lawyer like his dad. He’s an amazing communicator.”

As Lesnar’s mouthpiece since 2012 — he likens the role to a White House spokesperson — Heyman has been ringside for three WrestleMania main events. More than that, this most recent WWE run is notable for what it hasn’t been: volatile.

Even in an industry brimming with hucksters, addicts, and self-loathing narcissists, Heyman has had a turbulent career — 31 years filled with fines and suspensions, bankruptcy and pink slips, explosive arguments, and endless grudges. “The first time I met Paul Heyman was crazy,” remembers the former ECW star Taz. “It’s two in the afternoon. The arena is empty. All of a sudden I hear nonstop cursing and yelling. Paul is nose-to-nose with the owner of the promotion, screaming and fighting over a creative disagreement. I worked that night, but Paul got fired.”

Perhaps at 52 years old, Heyman, a notorious micromanager, has mellowed. “I think a control freak stays a control freak,” Heyman says. “But I’ve certainly learned how to prioritize what needs to be controlled and what doesn’t really matter.”

Heyman was skeptical about returning to WWE. “It ended so badly,” he says about his bitter exit in 2006. “I couldn’t imagine it would be a happy experience.” The relationship with WWE chairman Vince McMahon began to sputter soon after Heyman was hired in 2001 when he walked into the company weeks after his promotion, Extreme Championship Wrestling, went under.

Heyman initially flourished, moving from the announcer’s table to a manager’s role to head writer of SmackDown, the B-show to Raw. Despite high ratings and critical acclaim, Heyman was ousted from that role less than eight months into the gig after one too many clashes with McMahon consigliere Kevin Dunn. “I was fighting battles,” Heyman says, “that in the big picture made no sense for me to fight.” And yet he wasn’t fired. Heyman bounced around the creative team until 2006, when McMahon placed him in charge of a revived version of ECW.

The idea was doomed from the start. Heyman, who once retained full creative control of ECW as owner and booker, was now an employee answering to McMahon and his daughter, Stephanie. And when Heyman’s plans to push CM Punk, then a WWE newcomer, at the December to Dismember pay-per-view event were denied, he wanted out. McMahon sent him home the next day.

Burned out on the business, Heyman retreated to his New York home to focus on Looking 4 Larry, which he had cofounded earlier in 2006. He launched the online series The Heyman Hustle for The Sun and wrote a wrestling column for the British tabloid. He made a bid to enter the world of combat sports, but an attempted buyout of the MMA promotion Strikeforce fell through in 2007, as did talks with TNA, then the second-largest wrestling promotion in North America.

“When he is on his game, he is as good as there ever has been at establishing a point and supporting it.” — Legendary announcer Jim Ross

Heyman had demands: 10 percent ownership, the ability to take the company public, and the release of the roster’s older wrestlers. TNA chairman Dixie Carter balked at the last request. “She didn’t want to get rid of the legends,” Heyman says. “They had a different vision than I did and I wasn’t willing to devote my life to something that I was sure was a losing vision.”

His exile lasted until May 2012, a month after Lesnar’s reappearance in WWE. The former UFC heavyweight champion, who’d had his own falling out with McMahon in 2004, had just re-signed, but looked lost in a disastrous segment on Raw. Lesnar had a suggestion for fixing his character: Make Heyman an offer he couldn’t refuse. WWE did, and he did not turn it down. And to the surprise of many, even Heyman, the reunion is ongoing.

Heyman says he hasn’t had a “vicious” argument with management since returning, despite the occasional disagreement. “Brock Lesnar vs. the Undertaker at WrestleMania, there was a lot of discussion about that. Brock Lesnar vs. Roman Reigns at WrestleMania, there was a lot of discussion about that,” Heyman says. “We all handle it differently now, though. Vince does. Brock does. And so do I.”

Heyman grew up in Edgemont, New York, an upper-middle-class enclave just west of the Bronx, with the knowledge that he was his father’s greatest pride and his mother’s deepest disappointment. “I think Jesus, Buddha, Muhammad, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Moses, and Zeus would have all fallen short of my mother’s goals. My mother was a fierce human being,” he tells me. “She wasn’t born that way. That was the evolution of her mind coming out of the Holocaust.” A survivor of the Lodz ghetto, Auschwitz, and Bergen-Belsen, Sulamita Szarf lost her mother, Hinka, and sister, Judith, to the gas chambers in Auschwitz.

Szarf settled in the United States after the war, working as a nurse at Montefiore Hospital in the Bronx. She met Richard Heyman, a World War II vet and the son of a Hungarian immigrant, at a party, and married him six months later. Their son Paul was born on September 11, 1965.

Heyman got hooked on wrestling in 1975 after watching a Superstar Billy Graham promo. “He just entertained the living shit out of me,” he says of the trash-talking former WWWF champion. “I remember saying, ‘I want to see more.’” For an industrious kid who opened a movie collectibles business at 11, hustling his way into the wrestling business was an inevitability.

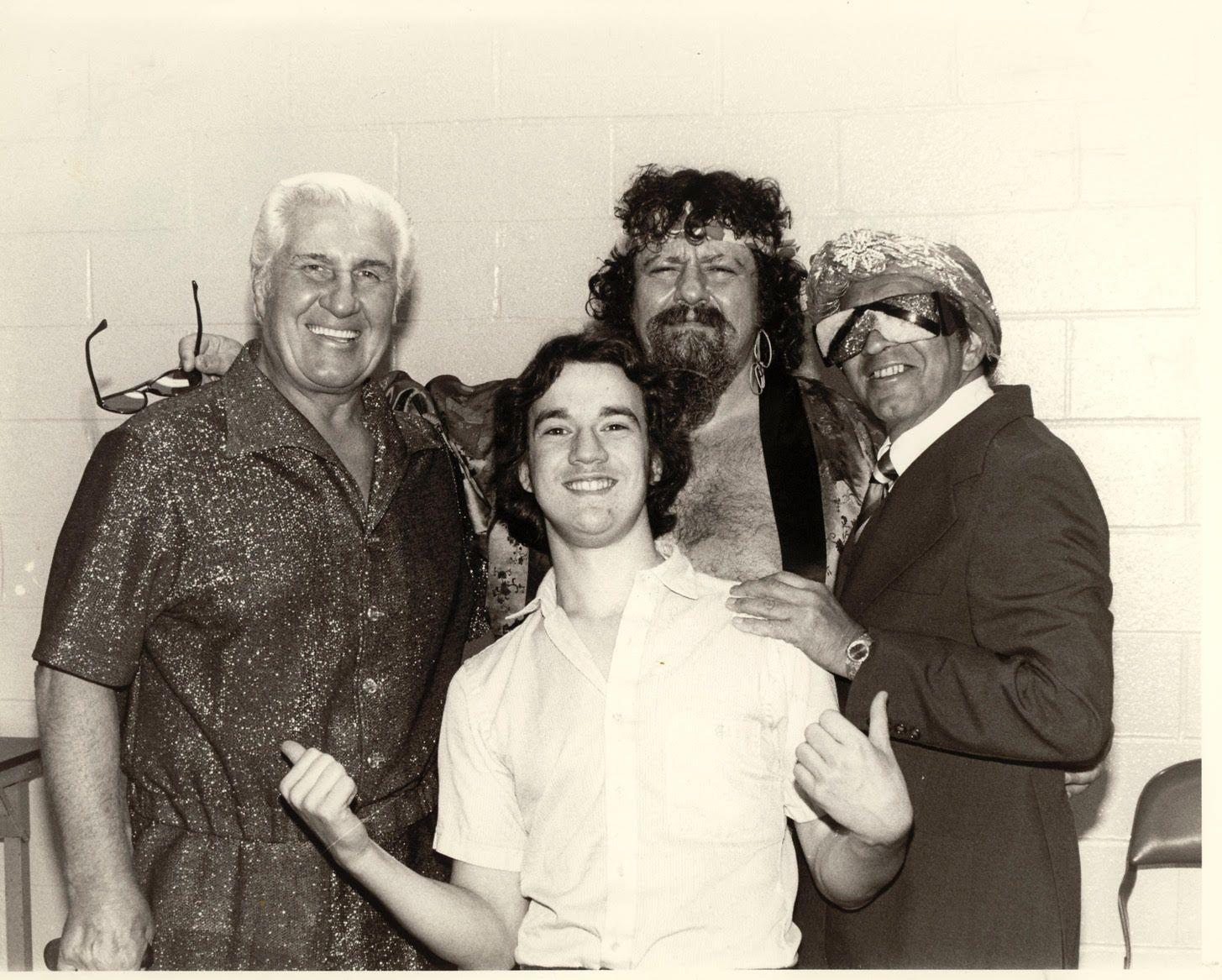

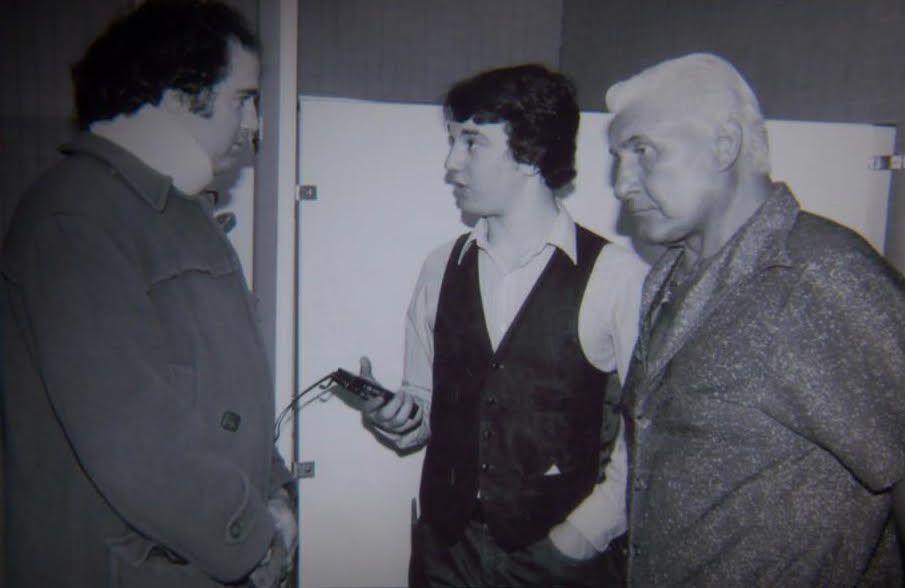

At 14, he finagled a press pass for a WWF event at Madison Square Garden, where he photographed Vince McMahon Sr. and Andre the Giant, making his first 50 bucks off a McMahon in the process. Traveling from his home to MSG for WWF shows then became a habit. He befriended the Grand Wizard, Ernie Roth, who introduced him to Freddie Blassie and Lou Albano. The managers dubbed the Three Wise Men of the East used Heyman as a one-man focus group, and, wouldn’t you know it, the kid had opinions — strong opinions — and damn good ideas about the wrestling business.

Soon Heyman was traveling to shows and meeting more people in the industry. He once sneaked into a closed-door NWA production meeting in North Carolina. “I want to learn from you, Dusty,” he told Dusty Rhodes after his cover was blown. He was already editing three wrestling magazines and doing play-by-play for a small independent promotion on the side. Still, he graduated from SUNY Purchase during this time with a degree in political science and communications.

Within a few months he was producing Friday nights for Studio 54, where he had worked his way up from photographer to publicist to promoter. For his first event, he had a brilliant idea: a wrestling show. It was the next logical step. He made up some hooey award for Ric Flair and convinced NWA head Jim Crockett to fly Flair, Rhodes, and Magnum T.A. to New York. On August 23, 1985, Paul Heyman became a wrestling promoter.

The wrestler Bam Bam Bigelow encouraged him to become a performer in the ring, but Heyman resisted. “I was a champion tennis player and swimmer until I was 13 years old, but I didn’t have enough athletic ability to be the best [wrestler],” Heyman tells me. “I didn’t want to be second best.” Besides, he was more interested in working behind the scenes as a booker. But to do so he needed an entry point. He decided to follow in the footsteps of his mentors and manage. He had the perfect stage name, too: Paul E. Dangerously, an homage to Michael Keaton in Johnny Dangerously.

Heyman made his ringside debut in January 1987 in Salem, Virginia, managing the Motor City Madmen. From there, he lived the itinerant lifestyle of a go-getter seeking his big break. Kevin Sullivan brought him to Florida. Bam Bam Bigelow took him to Memphis, where he shaved Jerry Lawler’s head. “That crowd reaction was exactly what some people spent their whole career chasing,” Heyman says. “It was happening in slow motion for me.” He managed the Original Midnight Express in the AWA, which put him on ESPN’s air every afternoon. A brief stop in Alabama as “Hot Stuff” Eddie Gilbert’s main man followed. He booked Windy City Pro Wrestling out of the old Chicago International Amphitheatre on Halsted Street. Then it happened. He got the call.

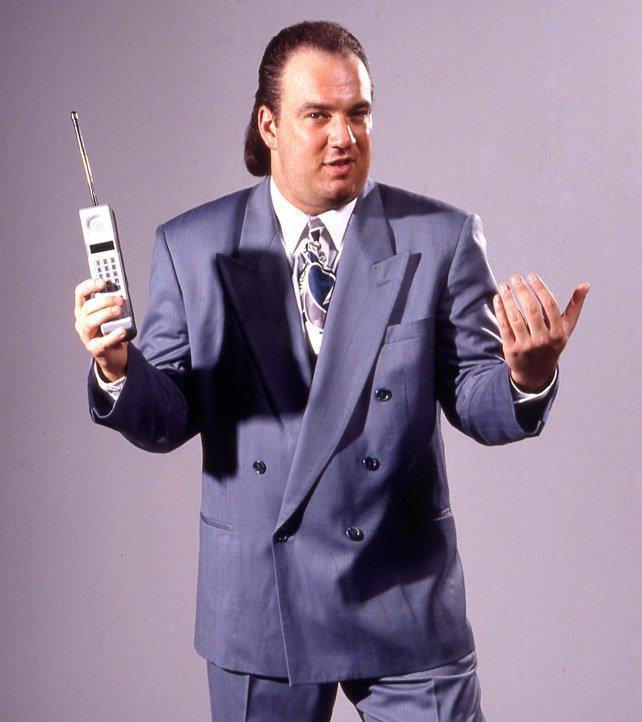

In fall 1988, Heyman signed with Jim Crockett Promotions. The National Wrestling Alliance. Center stage in Atlanta, Georgia. Superstation TBS. Saturdays at 6:05 p.m. And he made a splash in his debut, smashing a cellphone over the head of Jim Cornette, the loudmouth manager of the Midnight Express, known for whacking opponents with his tennis racket. This was the big time.

The oversize mobile phone was a staple of Heyman’s Paul E. Dangerously shtick. Yuppie scum personified, Dangerously bragged about his Wall Street connections, his cash, and his lawyer daddy. Cokehead sunglasses, suspenders, and a glorious mullet were his trademarks. He was a baby Gordon Gekko. And when he opened his mouth, my God, the vile things he said. In an era when managers went for laughs (think Bobby “The Brain” Heenan), Dangerously made it personal. It was a different kind of heat.

He had learned from the best. The Grand Wizard was brilliant with bullet points, always selling the next show and next challenger. Blassie taught him that wrestling was Shakespeare. “Play up, never play down,” he’d tell him. “You’re larger than life!” Albano, meanwhile, was a maestro of feeling a crowd. Heyman’s greatest attribute, however, was his ability to stoke enmity. He was a natural antagonist. Like all the best gimmicks, this one was not much of a stretch. He would push and prod, but never retreat. Your honor, I’m just an advocate. He was a loud, abrasive know-it-all from NYC. A real heat-seeker. And it occasionally got him into trouble with the boys.

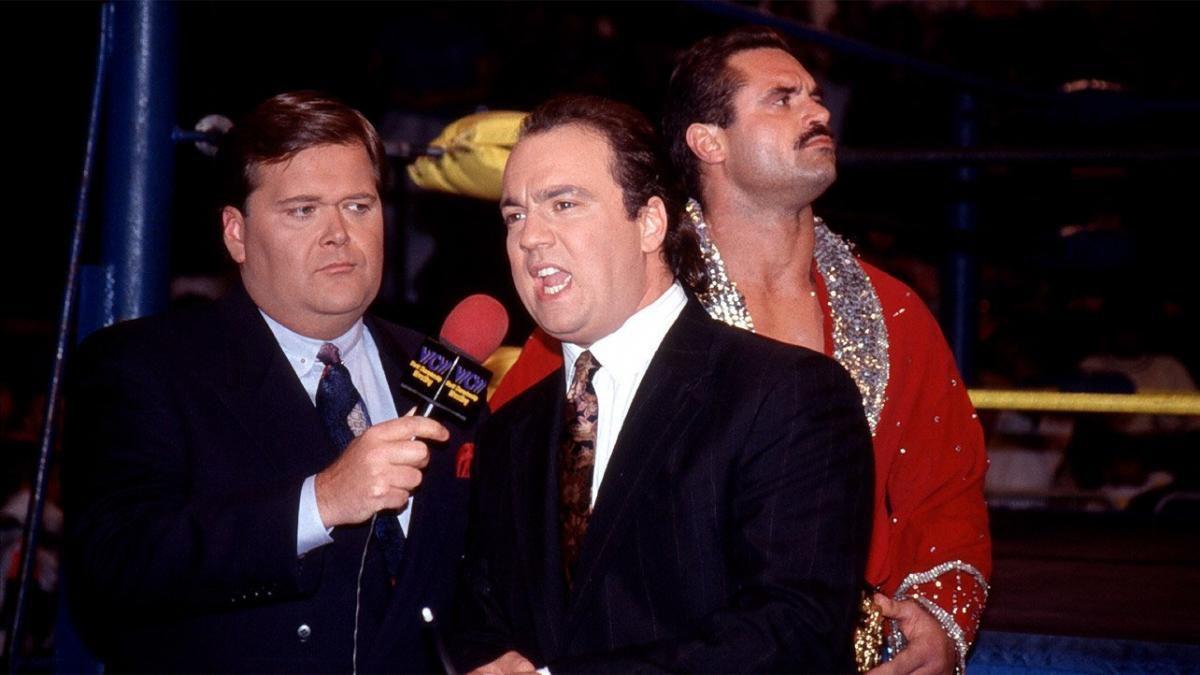

Before arriving in WCW, Heyman had acquired a reputation for not playing well with others, most notably Jerry “The King” Lawler in Memphis. In Atlanta, he ran afoul of Ric Flair, who, in addition to being World Champion and “The Dirtiest Player in the Game,” added head booker to his CV in the summer of 1989. Flair then arranged to consolidate his power. In his eyes, the 23-year-old Heyman was abrasive and annoying, and hadn’t paid his dues. Perhaps more significantly, Heyman was also friends with Eddie Gilbert, one of Flair’s backstage rivals. And so in September of that year, Flair canned Heyman for not following his instructions during a pre-taped promo. “You’re fired,” Flair told him. “Fuck you.”

"Tell me somebody who was in the NWA who was relevant then and relevant now. Sting’s not. Lex Luger’s not. It’s Ric Flair and Paul Heyman. Tell me someone from that entire era who is relevant today. Vince McMahon. Jerry Lawler. And of all those people that I’ve named, how many of them are in a prominent position on television today? The only one is me.” — Paul Heyman

Heyman would not go quietly. He sued Turner Broadcasting, which had purchased Crockett Promotions in late 1988 and changed the promotion’s name to World Championship Wrestling. But Jim Ross brokered peace, and the suit was settled. When Heyman got his job back in spring 1990, he was assigned to a young redheaded Texan named Mark Calaway, better known as the man who would become the Undertaker. (Of the future Dead Man, Heyman says he was “shockingly mature for someone so new to the industry.”) Heyman encountered Flair in Pittsburgh at his first show back. “He walked up to me in the locker room and said, ‘What are you doing after the show?’ I said, ‘I don’t know. What am I doing after the show?’” He says, ‘Meet me at the bar and we’ll get a drink,’” Heyman says. “We drank until we closed down the bar at two, three in the morning — and you know me, I’m not a drinker. We caught a 6 a.m. plane … and to this day have never talked about the night he fired me.”

Heyman declined to participate in the recent 30 for 30 documentary about Flair. “Thirty people said yes, while the Rock and [Stone Cold Steve] Austin said no,” he says. “I thought the list of people not doing it was more impressive than the list of people doing it.”

Just as he smoothed things over with Flair, Heyman made new enemies. Executives called him the “New York Jew” behind his back. But by the end of 1991, after returning from another suspension, the Jewish guy from New York was leading the top heel faction in the industry, the Dangerous Alliance. New management then demanded he take a pay cut. He declined, was written off television, and then, once again, he sued Turner. The litigation became hostile to the point of no return. Heyman claimed victory once the parties settled. “There was a definite understanding that they were very much in the wrong,” Heyman says, still chuckling at the size of the settlement.

Over the course of several conversations across six weeks, I asked Heyman about past examples of his bad behavior. He always responded in a similar fashion. For him, it is a kind of code.

“It’s what was necessary for me to survive in that environment,” he says. “Tell me somebody who was in the NWA who was relevant then and relevant now. Sting’s not. Lex Luger’s not. It’s Ric Flair and Paul Heyman. Tell me someone from that entire era who is relevant today. Vince McMahon. Jerry Lawler. And of all those people that I’ve named, how many of them are in a prominent position on television today? The only one is me. So, how? The manner in which you were treated behind the scenes did not promote longevity. You were going to be used up and spit out. And here I am as the advocate of the number-one attraction, the highest-paid commodity, the top champion on the flagship show in the company that owns 99 percent of the market share. Obviously whatever I was doing back then, that people perceived as career suicide, gave me the ability to survive long enough to have a longevity that no one else enjoys.”

One night near the end of his time with WCW, Heyman was stoned and watching MTV when the video for LL Cool J’s “Mama Said Knock You Out” came on. Something clicked. Ladies Love Cool James, filmed in black and white, training in his grandma’s basement. A big star in an intimate venue. High quality on a low budget. Gritty. Hard.

Pro wrestling was awash in bad gimmicks and goofy story lines at the time. It was the age of Doink the Clown and the Lex Express in WWF. WCW, meanwhile, was producing mini-movies starring evil little people. Wrestling wasn’t cool. Heyman envisioned a new promotion that could be the Nirvana to their hair bands.

Heyman is now regarded as one of the most gifted futurists in wrestling. He has achieved that reputation not because of an ability to pinpoint young talent — though he had the sagacity to identify the Undertaker, Austin, Lesnar, and Punk as potential stars early on — but rather through his uncanny intuition. Having that knack to gaze into the future and monetize that vision is the most sought-after talent in an industry where success is predicated on finding the next big thing.

In the early 1990s, Heyman recognized that years of neglecting males ages 18 to 29 in favor of marketing to children had made wrestling lame to the very demographic that should constitute its base. So in September 1993, when Heyman took control of a small independent promotion based in Philadelphia, he targeted that audience. There was one problem: He thought that its name, Eastern Championship Wrestling, was too regional even though it was an established brand. The fans were already chanting “ECW.” The new moniker would reflect the concept that Heyman envisioned when he saw LL on MTV, and in August 1994, Extreme Championship Wrestling was born.

With its TV-MA themes and action, ECW would revolutionize the industry. The ring work was a kinetic mix of styles that were both highbrow (pure mat-based wrestling and high-flying lucha libre) and lowbrow (the violent, bloody brawls that became ECW’s calling card). ECW’s storytelling was edgy and uncouth. A lesbian angle got the promotion kicked off several cable affiliates, but blood feuds between three-dimensional characters like Tommy Dreamer and Raven was where ECW distinguished itself from the competition. And the syndicated television program, broadcast late at night, packaged together a one-hour adrenaline rush combining herky-jerky camerawork, quick editing, and music (rap and metal, of course) with sex, violence, and profanity. Heyman knew what the fans wanted. He was one of them.

“I never looked at ECW as wrestling. I always considered it more of a theology,” he tells me. “I don’t know whether I had or didn’t have a messianic complex during that time. But I bought into the movement as much as, if not more than, anybody else. If I sold anyone on the religion of extreme, I was its number-one customer.”

In a business defined by carny BS and swerves, Heyman’s passion resonated with the roster, from the young idealists to the jaded vets. And when he stood in front of them before a big show and delivered a fiery motivational speech, they responded, leaving their blood, sweat, and tears in the ring. “We believed in the boss. We believed in the vision. We saw the impact we were having on the wrestling business,” says Bubba Ray Dudley, who has compared Heyman to the cult leader David Koresh. “When Paul made his speeches, you truly wanted to go to war for him. Every ECW wrestler was willing to die in battle for the company. I don’t mean that figuratively, but we were ready to do whatever it takes for the world to notice us.”

“I never looked at ECW as wrestling. I always considered it more of a theology. I don’t know whether I had or didn’t have a messianic complex during that time. But I bought into the movement as much as, if not more than, anybody else. If I sold anyone on the religion of extreme, I was its number-one customer.” — Paul Heyman

ECW didn’t last. By the late 1990s, WWE, and to a lesser extent WCW, began co-opting certain aspects of the ECW brand — the hardcore matches, the beer drinking and vulgarity — and presenting them to the world with a far bigger budget behind it. WWE branded it “Attitude.”

Despite thriving gate receipts, healthy merchandise sales, and pay-per-view distribution, ECW struggled financially. Heyman needed investors and advisers. Talent raids by WWE and WCW crippled the roster, and ECW lost its cable deal with TNN in October 2000. Heyman met with USA and Fox Sports, but failed to reach an agreement with either network. Heyman then struggled to make payroll, once even borrowing $250,000 from Jimmy Iovine to make it through a two-week cycle; around that time Vince McMahon lent him $500,000. It wasn’t enough. By the end, Heyman was bouncing checks and lying to his wrestlers. “I got the company to the next day, and sometimes that’s an unpleasant task,” he said in the documentary Ladies and Gentlemen, My Name Is Paul Heyman. “You lied to survive.” Heyman, who obtained full ownership of ECW in April 1995, maintains he never drew a paycheck, and says he financed the company with his settlement money, stock market earnings, and $4 million from his parents.

After the company closed down in April 2001, the narrative threading the many, many ECW obituaries — including the WWE-produced 2004 documentary The Rise & Fall of ECW — was that Heyman was a creative genius but an awful businessman. For all his booking prowess, he couldn’t keep ECW afloat. He is sensitive about that label. “If we had closed the television deal in 2000, well, then I’d be the genius who created a startup, went up against two billionaires, outlasted Ted Turner, and challenged WWE at their own game,” Heyman says. “But we didn’t get distribution. Therefore, I’m the dumb shit that can’t be labeled a good businessman.”

In the never-ending battle between art and commerce, Heyman stands with the latter. Having filed for personal bankruptcy, he had hard but necessary decisions to make after ECW went under. He had to earn. He went to WWF even though TNN, the network he had battled for 18 months, broadcast Raw, because grudges don’t pay bills.

“Brock was always known as a great wrestler. Now he’s become a great attraction. Part of that attraction — a big part — is Paul Heyman.” — Former ECW star Taz

The situation is different now. When he grabs the microphone, with or without Brock Lesnar beside him, and the audience recites his signature opening line (“Ladies and gentlemen, my name is Paul Heyman …”) right along with him, he knows the promos aren’t meant to get himself over. The promos are meant to draw money. He may be the advocate for the reigning, defending, undisputed Universal Champion Brock Lesnar, but he knows his true role within WWE. “I am a revenue facilitator for World Wrestling Entertainment,” he says. “And I serve at the pleasure of the chairman now by driving network subscriptions and selling story lines, characters, matchups, and events.”

There have been two Paul Heymans in WWE: the angry, Steve Bannon–like disruptor bent on chaos, the dark and sinister operator who wears a long ponytail and leather trench; and then there’s today’s Heyman, the banker in the three-piece, his hair now a respectable power doughnut, standing beside his only friend in the world, Brock Lesnar.

Heyman met the man he’d christen “The Next Big Thing” in 2001. At the time, Lesnar was wrestling dark matches off television, and, according to Taz, he was getting terrible advice; WWE agents were instructing Lesnar to wrestle like an immobile monster. Seeing the potential, Heyman became a mentor. “No one had seen an athlete like this,” Heyman, ever the promoter, says. “Brock was a 285-pound NCAA Division I heavyweight champion who could run the 100-yard dash in Olympic qualifying time.” He revamped Lesnar’s gimmick to emphasize his explosiveness and athleticism. A beast was born.

Lesnar compiled a spectacular rookie campaign, defeating Hulk Hogan, the Undertaker, Kurt Angle, and the Rock, winning the WWE Undisputed Championship, the 2003 Royal Rumble, and the main event of WrestleMania XIX. By this point, Heyman and Lesnar, the son of a dairy farmer from South Dakota, had grown close. Despite their divergent backgrounds, the men shared similar values. Both revered their parents and longed to get rich in the business. Both were also expecting their first child. “It was an instant item on which we could bond,” Heyman says. “That was our priority, more so than if [the show] is going to be good this week.”

Heyman says their families still get together, but scoffs when I ask if Lesnar can comment. “Brock won’t talk to you,” Heyman says. “I don’t even think you’d get a ‘Fuck off’ out of him.”

“I think it’s great that Paul’s loyalty in character stays with Brock,” Taz says. “I think of Brock Lesnar and Paul Heyman together as a package. Brock was always known as a great wrestler. Now he’s become a great attraction. Part of that attraction — a big part — is Paul Heyman.”

Never was this devotion more apparent than during the main event of SummerSlam in August, when Lesnar defended the Universal Championship against three contenders. At one point Heyman was hysterical as he watched Braun Strowman, Roman Reigns, and Samoa Joe take turns beating down Lesnar. Was the character upset because his meal ticket was losing or because his friend was in pain?

“A lot of people read into that,” Heyman says. He then prefaces his response with a long dissertation on the 1938 crime drama Angels With Dirty Faces. At the end of the film, James Cagney’s character, the gangster Rocky Sullivan, stands defiant even in the face of death. Before Sullivan’s execution, his childhood friend, a priest played by Pat O’Brien, pleads with him to die like a coward, so that the neighborhood kids won’t idolize him. Like a dirty heel, Sullivan refuses. But as he walks to the electric chair, he cries for mercy. The filmmakers leave the story ambiguous as to whether Sullivan’s turning yellow was an act — as does Heyman. “I tried to consciously play it as all of the above.”

And though Heyman once double-crossed Lesnar back in 2002, he doesn’t think it makes sense for his character to do so again. “No,” he says. “Not anymore.”

How much longer does the Heyman-and-Lesnar act have left? Earlier this year, Heyman promised on behalf of Lesnar to leave WWE if he lost at SummerSlam. He rallied to win, but his contract reportedly expires after WrestleMania in April 2018. There is speculation that he’s contemplating yet another return to UFC. Heyman won’t comment on Lesnar’s status other than to confirm that he is scheduled to work Survivor Series on Sunday, Royal Rumble, and WrestleMania. As for his own pact, Heyman was unsigned in 2016 from WrestleMania until just before SummerSlam; he was off television during that time as Lesnar was away preparing for his return at UFC 200. When the deal was completed, Heyman and WWE agreed to never negotiate in public. “I don’t want to disclose when my contract ends because then I’d be going back on my word,” he tells me. “Then I’m starting my negotiation now. I don’t want to do that.”

Arriving in a rush at a Korean barbecue restaurant in Yonkers, Heyman smells like cologne and is breathing heavily. He sits in the back of the restaurant, which is about five minutes from his house, and attacks a plate of chop chop with a fork. Heyman ate here frequently with his father until he died in 2013. “He was my hero, still is,” Heyman says. “Most complete human being I ever met in my life.”

When Heyman was a teenager, his father tried to teach him a lesson in humility. He told Paul that if he died tomorrow the earth would still revolve around the sun. A week later, the earth would still revolve around the sun. And one hundred years from then the earth would still revolve around the sun. “So, my boy, get the fuck over yourself,” Richard told him. “You’re not that important. To me you are, but not to this planet.”

“I don’t want to disclose when my contract ends because then I’d be going back on my word. Then I’m starting my negotiation now. I don’t want to do that.” — Paul Heyman

Heyman reiterated the aphorism to his children Azalea, 15, and Jacob, 13, after their grandparents died. “They were both hard events for me, but the earth still revolves around the sun,” he says, his voice wobbling. “My father was right. My parents weren’t that important. To me they were. To my children they were. But in the scope of things, they weren’t.”

In the scope of his career, it’s not important what comes next for Heyman. He’s already had four major arcs in his wrestling career: everything leading up to the Dangerous Alliance, ECW, his first stint in WWE, and this run with Lesnar. He is up for a fifth defining career moment, but only if Lesnar steps away. “As long as Brock is in WWE,” he says, “I don’t think it makes sense to work with someone else.”

When he gets going, he expounds on the future of the business. He sees money in Enzo Amore once he moves on from the catchphrases. The Miz, he believes, is still learning nuance and idiosyncrasies. “How good is he going to be in a year?” When Braun Strowman evolves past being merely the monster, watch out. And despite how much fun Kevin Owens has been as a villain, Heyman says the big money for the Quebecer will be as this generation’s Dusty Rhodes.

And that’s just WWE. He looks at the Bullet Club — Kenny Omega, the Young Bucks, Marty Scurll — as crowd-pleasing and forward-thinking disruptors. He’ll tell you that Will Ospreay is in the conversation for best wrestler in the world. The future is a more comfortable place for Heyman.

“I’m not the old boxer sitting in the basement watching black-and-white footage of themselves looking back on the good old days,” he says. “I don’t get nostalgic. The good old days, to me, are ahead.”

Even more comforting about the future is that he knows one day he will be gone. And on that day, the earth will still revolve around the sun.