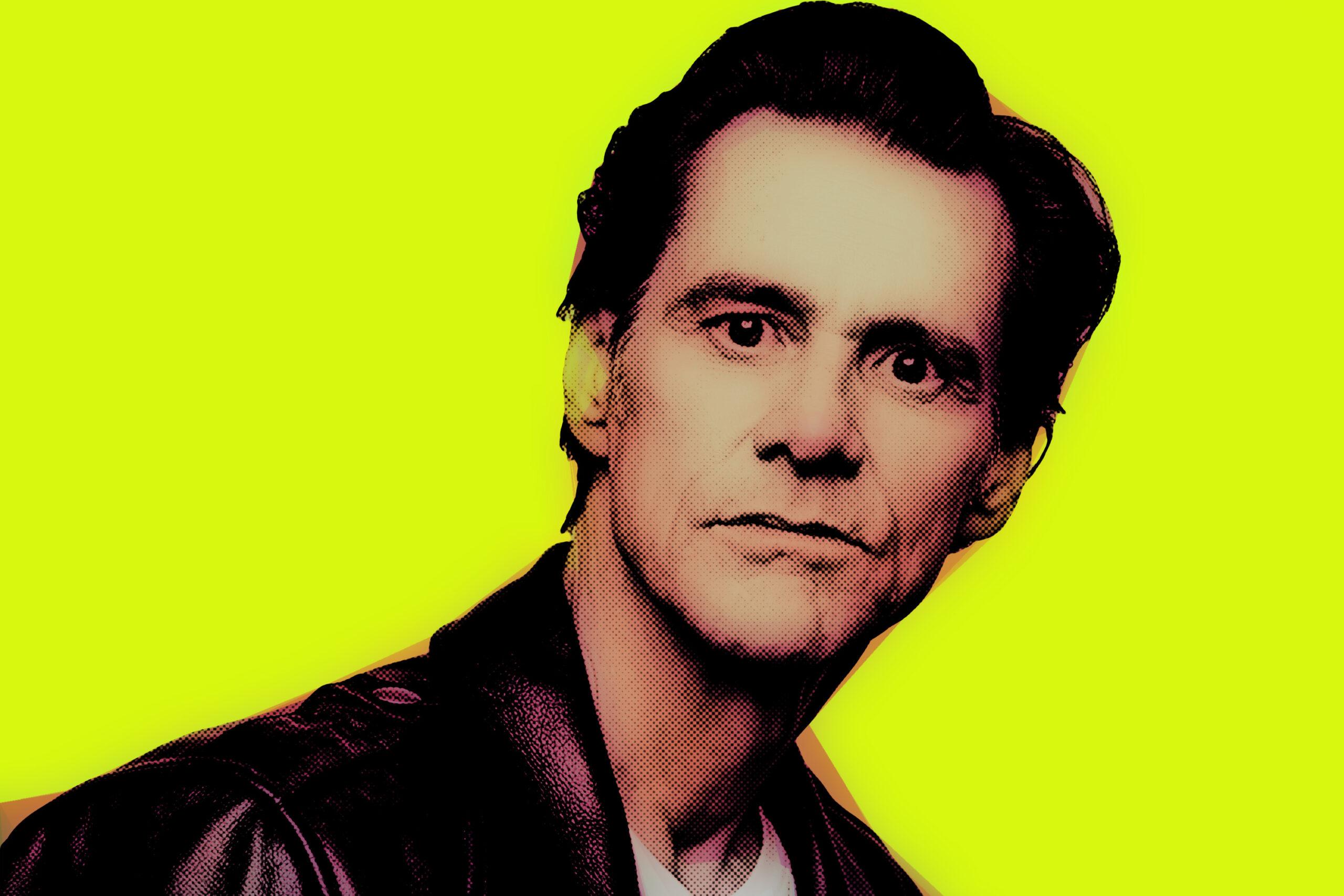

“Wow, we got into some crazy shit there, man.” This bewildered voice comes from off-camera at the conclusion of Jim & Andy, the new Netflix documentary about the making of the 1999 Andy Kaufman biopic Man on the Moon, which starred Jim Carrey at the dizzying height of his fame. The documentary is over; the end-credits song (a warped version of R.E.M.’s “Man on the Moon,” obviously) is already playing faintly in the background. And there sits modern-day Jim Carrey, with his grayed suave-werewolf beard and piercing stare, perfectly lucid and alluringly calm and frightfully intense. The thing Carrey has just said, on-camera, to prompt the crazy-shit response off-camera is, “I wonder what would happen if I decided to just be Jesus.”

The full title of this documentary, which is directed by Chris Smith and premiered Friday, is Jim & Andy: The Great Beyond—Featuring a Very Special, Contractually Obligated Mention of Tony Clifton, which gives you some idea of the meta gymnastics on display here. Basically, a camera crew followed Carrey around as he made Man on the Moon, adhering to the infamous Method-acting school by refusing to break character when portraying both Kaufman and Kaufman’s own famously boorish and loathsome alter ego, Tony Clifton. Carrey’s costars, from Danny DeVito to Paul Giamatti to a valiantly unfazed Courtney Love, suffered or at least politely winced accordingly. (DeVito, through teeth gritted spiritually if not literally: “This is so bizarre. It’s really great. He’s exactly the way Andy was. Exactly.”)

Meanwhile, present-day Jim Carrey provides talking-head commentary that sometimes directly responds to this old footage, until it stops even trying to do that:

I’ve stepped through the door. The door is the realization that this [gestures at documentary set], us, is seaside. It’s the dome. This is the dome. This isn’t real. You know? This is a story. There’s the avatar you create, the cadence you come up with that is pleasing to people and takes them away from their issues and makes you popular. And at some point you have to peel it away. It’s not who you are.

This is a lot to deal with, mostly on purpose. Andy Kaufman was an easy-to-appreciate, harder-to-love comedy genius whose primary weapons were cognitive dissonance and profound discomfort—the audience’s discomfort, but also, usually, his fellow actors’ discomfort. When Kaufman was on camera, his was the least-important face on camera: The magic happened as you read the faces of everyone else as they vacillated between delight and confusion and what sure seemed to be genuine rage, the border between those emotions electrifyingly fluid. Were they in on the joke? Were they the joke?

Add Jim Carrey, a cartoon character of a real person making his play to be a Dramatic Actor by portraying a subversive tragic hero of a cartoon-character comedian hell-bent on blurring the lines between reality and surreality, and what you’ve got is—and this bears repeating—a lot to deal with. Jim & Andy’s resulting nesting-doll identity labyrinth is fascinating, and occasionally somewhat upsetting. It is possible to watch this film and feel very warmly toward both past and present Jim Carrey, but also conclude that he behaved terribly on the set of Man on the Moon in a way that likely did not improve the quality of that film, and still wouldn’t be justified even if it had. Strip away the Kaufman mystique and the implied devotion to Serious Acting and you have a megastar behaving the way only a megastar is permitted to behave. Carrey’s high jinks are mostly whimsical and never quite deplorable. But the fact that this footage is airing now, almost 20 years later, feels like a tacit acknowledgement that he’s no longer a big enough star to get away with it. The more important lesson is that nobody should.

It is difficult to convey in 2017 exactly how famous and dominant Jim Carrey was for much of the ’90s. In 1994 alone, he starred in Ace Ventura: Pet Detective, The Mask, and Dumb and Dumber, a one-man holy trinity of manic slapstick comedy. “Jim had become one of the biggest stars on the planet,” a Jim & Andy title card reads, and that statement is not even slightly hyperbolic. He started gunning for critical acclaim and Oscar love with Peter Weir’s absurdly prescient 1998 reality-TV dramedy The Truman Show, with Man on the Moon coming the following year and Michel Gondry’s hyper-emo 2004 black-rom-com, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, completing the Serious Jim trilogy. Result: plenty of critical love, but no Oscars. He seemed to take it in stride, though his version of “in stride” likely differs greatly from yours.

Carrey’s 21st-century arc has been … dark. Confusing. Unsettling. His talking-head performance in Jim & Andy may be his best in years, if only by default. His impression of Man on the Moon director Miloš Forman, for example, is by far the single funniest thing in this movie: “I AM INTIMIDATED!”

In the actual vintage backstage footage, Forman looks less intimidated than nobly exasperated. “You have to give me a chance to make a movie! You have to give me a chance to make a movie!” he shouts at his most animated; usually, his feelings about Carrey are more diplomatic. (“He mellows after lunch.”) There is, however, no evidence here that Carrey actually mellowed at all. His Method-acting antics—as “Andy,” and especially as “Tony”—range from the harmless (turning up radios too loud) to the worrisome (lots of frivolous verbal abuse lobbed at fellow actors and crew members alike) to the actively hostile (a few flung cups of water, an emphatic bout of spitting). This is “Jared Leto in Suicide Squad”–type stuff, and while none of these antics individually rise above the level of mild-to-pronounced irritation (on his coworkers’ part, and also yours), the accumulated unease gets harder and harder to process.

The biggest target of Jim-as-Andy’s ire, and the most sympathetic figure in the documentary by a long shot, is poor Jerry Lawler, professional wrestler and real-life Andy Kaufman co-conspirator. In the ’90s footage, Lawler takes great pains to point out that Kaufman was always very respectful and cordial behind the scenes, and their on-camera acts of subversion were true collaborations. But Carrey decided to simply treat Lawler like a jerk all the time: “I really liked him, but Andy felt it was necessary for him to stay in the character, so Andy stayed in the character.”

So Lawler endures the water tossing, and the spitting, and so forth. Unfortunately, there are also usually multiple women, both crew members and onlookers, in the frame, which curdles the goofy fun into something dark and sour and especially resonant given the conversation Hollywood is having with itself in 2017. Lawler snaps twice on-camera, first throttling Jim-as-Andy while yelling, “Anytime I want to, I can do this to you!” The second altercation, during a big wrestling scene, is severe enough that Carrey winds up in the hospital, a highly publicized fiasco that happened to precisely mirror Andy Kaufman’s version of real life.

Trust no one. But all this subversion very clearly terrorized quite a few innocent bystanders and crew members just trying to do their jobs. Even the sillier moments here are charged with a severe discomfort: At one point Jim-as-Andy starts arguing with the actor playing Andy’s father as they lounge in a makeup trailer, and amid the invective the camera pans to a makeup artist with tears in her eyes as she says, “That reminds me of my dad.”

Carrey’s modern-day explanation for why all this footage went unseen for nearly 20 years is very simple: “Universal decided at that time that they didn’t want me to allow any of that to surface, so that people wouldn’t think I was an asshole.” Big smile. “Those were the words exactly that came back to me: ‘We don’t want people to think Jim’s an asshole.’” Big laugh. Later, we’re given reason to doubt this explanation, just to keep the cognitive-dissonance theme going. But by then your feelings about Carrey as both an actor and a man-as-actor have likely grown more complicated.

Jim & Andy doubles as a pocket history of Carrey’s career, from his comedy-club come-up (which he helped dramatize in this year’s Showtime series I’m Dying Up Here) to his In Living Color breakout to his ’90s blockbuster supernova to his prestige plays. (At times The Truman Show—arguably a much better movie, and inarguably a better-aged one—gets as much play as Man on the Moon.) The question hovering over all of this is: What happened to this guy? Carrey’s lengthy hiatus and recent erratic public behavior suggest a man who now speaks very eloquently about how he’s totally at peace with himself in a way that suggests that he remains mercilessly at war with himself, or at war with the public’s lasting perception of him as a mere multiplex clown. Both the old footage and the present-day commentary on that footage hints at a darkness that Famous ’90s Jim radiated outward, and Reclusive 2010s Jim now trains inward. The world—or at least the set of the next Jim Carrey movie—is better off. As for Jim Carrey himself, judge for yourself.

At one point late in Jim & Andy, Carrey fires off a lengthy monologue about the displeasures of massive fame and the total pleasures of self-annihilation. “I don’t want anything,” he says. “That’s the craziest thing—that’s the weirdest thing to say in a place like America, where I have no ambition. I really, truly don’t.”

“Where do you think that will take you?” the offstage voice asks.

“Nowhere,” Carrey says. “I don’t have to go anywhere. That’s fascinating to me now. The disappearing.”