Every year before Thanksgiving, the president of the United States pardons a turkey. It’s a self-consciously quaint public ritual, humanizing in theory and embarrassing in practice. As legend has it, the tradition kicked off during Abraham Lincoln’s time in office. According to an 1865 White House dispatch, Tad Lincoln begged his dad to spare their would-be supper’s life. Tad’s plea didn’t result in an instant tradition, though. Turkey pardoning did not become a norm until the Ronald Reagan presidency, and the first official pardon occurred under George H.W. Bush’s watch. But enough turkey talk. There is another tale about the origins of the presidential pardon around Thanksgiving, and it doesn’t involve poultry: the story of Rebecca, a wayward raccoon from Mississippi, so scampishly cute that she inspired a notoriously stern president to open his home instead of his oven.

In 1926, President Calvin Coolidge — yes, Silent Cal, the “Sphinx of the Potomac” himself — was sent a live raccoon from an admiring citizen in the South, who recommended the critter as a Thanksgiving feast. (It had a “toothsome” flavor, he wrote.) Sending animals to the president to be eaten on Thanksgiving was a commonplace gesture of goodwill at the time. Melanie Kirkpatrick, who wrote a book about the history of American Thanksgiving, told me that the White House has received turkeys regularly since Ulysses S. Grant’s administration. “It was in the context of this Thanksgiving gift-giving tradition, where you’re sending food to the White House, that Rebecca was sent to the White House,” she said.

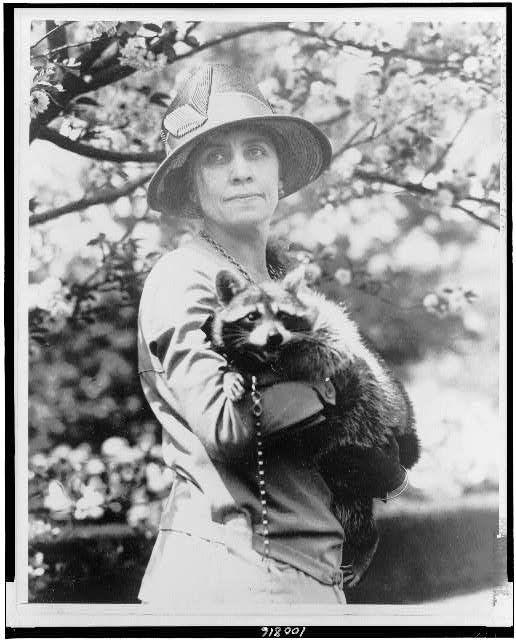

Coolidge, while a dedicated omnivore, was also mushy-hearted for animals. He simply could not bear to eat the raccoon. Instead, he decided to domesticate it. That Christmas, the Coolidge family named the raccoon “Rebecca” and gave their new pet a collar.

“Today, we think of raccoons as often carrying rabies. But apparently that was not the case until the 1950s,” Kirkpatrick said. “So it’s really gross to a lot of people today, to think that people made a pet of a raccoon that might have been rabid, but that is something that didn’t come to mind in the 1920s.”

Before we go any further, I’d like to clear something up. When I first found out about Rebecca, I excitedly told a table of my colleagues that people used to eat raccoons for Thanksgiving. My discovery was not met with enthusiasm. “No shit,” my coworker Justin Charity said, noting that he has personally eaten raccoon. I thought Charity was lying to me, but after I asked around on the internet, I learned that people still eat raccoons, both on Thanksgiving and not on Thanksgiving, all over the United States. Actor Anthony Mackie is an avowed fan, and the food website Serious Eats offers a tutorial on how to cook raccoon. After I sent out a request for raccoon-eating stories on Twitter, helpful strangers regaled me with surprisingly varied stories of their raccoon consumption, from snacking on a raccoon sandwich at a birthday party at Ole Miss to dining on a raccoon pot pie at a trendy downtown L.A. restaurant on Thanksgiving.

And many of the raccoon-eaters enjoyed the meat. “It depends a lot on the raccoon but it’s actually pretty close to turkey,” a new Twitter friend, whose grandfather would trap and cook raccoon soup in Northern California, told me. But not everyone I talked to was impressed by raccoon flavor. “It tasted dark and dirty, almost like black licorice but in meat form,” another Twitter friend (the one who had tried Los Angeles’s finest raccoon pot pie) said. “Suffice to say, don’t think I need to try raccoon ever again.”

“I was living with an anarchist survivalist named Roadkill Matt in rural Skagit County, Washington. Everyone in the county had his number and would call him if they hit something, and he would come get it and put it in his freezer. I watched him butcher it,” another new Twitter pal told me. “He sautéed a leg coated in an Italian seasoning blend and gave it to me. I couldn’t get past one bite. It tasted like garbage, which may have been due to its diet being mostly garbage.”

Rebecca escaped the Coolidges’ dining room table, so we’ll never know whether she had a “toothsome” flavor, or whether she’d taste like garbage. She certainly never looked like garbage — and she was known to eat corn muffins, not trash. By January 1927, Rebecca was all settled into the White House. “Rebecca has a comfortable place, now,” first lady Grace Coolidge wrote to White House housekeeper Ellen Riley, describing the ad-hoc raccoon den she’d ordered for 1600 Pennsylvania, complete with a homemade water dispenser. “Here she is snug and contented as can be.”

Riley would write about her adventures with Rebecca for The Home Magazine in 1937. (A copy of the article was provided to The Ringer by the President Calvin Coolidge State Historic Site, an incredibly helpful Coolidge-specific resource.) “We all loved Rebecca. I often brought her into the house for the afternoon and when the President came back from his office about five-thirty he would come in to watch her play. Her chief joy was to get into my bathtub with a cake of soap — she loved the suds and would splash around in the water for an hour,” Riley wrote. “Mrs. Coolidge took her one Spring to the Egg Rolling on Easter Monday and the children were delighted.”

Attempts to find Rebecca a mate did not go well. Riley described a day trip to Virginia to find a “suitable husband” for the pampered animal. “The President named him Reuben. Reuben did not like the White House atmosphere and one night he ran away,” Riley wrote. “The President remarked that Miss Riley’s matrimony venture wasn’t very successful.”

According to Riley, Rebecca was unhappy during a presidential trip to South Dakota, running away in the Black Hills. “So the next Summer we did not take her to Wisconsin but left her at the Zoo in Washington,” Riley wrote.

Rebecca did not like the zoo, either. “She did not get on well there — was very snooty to the common coons with whom she had to live and finally got sick and died,” Riley concluded. “She had always been very dainty about her food and I presume the Zoo fare did not suit her.” Poor Rebecca! A creature meant to be eaten, eventually killed by her own refined palate.

Despite Rebecca’s tragic end, I find her story comforting, as a reminder that tenderness can crop up in unexpected places — and as evidence that the White House has always been intensely weird.