“These so-called connoisseurs of Bob Dylan music, I don’t feel they know a thing or have any inkling of who I am or what I’m about. It’s ludicrous, humorous, and sad that such people have spent so much of their time thinking about who? Me? Get a life, please. . . . You’re wasting your own.” — Bob Dylan, 2001

Legend has it that you can see the Beatles in Bob Dylan’s John Wesley Harding. Look closely; etched into a tree at the top of the album’s cover, there are the visages of John, Paul, George, and Ringo. The photographer John Berg acknowledged the presence of the Fab Four in the image, just once, vaguely. “It’s like Dylan; very mystical,” Berg told Rolling Stone in early 1968. By this time, Dylanology had taken hold, with writers craning their necks to examine the runes in every scrap of output. There was a hunger for mythos. In Dylan, fans and journalists had found a local god worthy of a shrine. Even when there was hardly anything to understand — the misidentified carvings of a band’s image in a tree on an album cover? — meaning could be affixed to his detritus. Dylan was the ultimate projection, the proverbial rabbit hole to crawl down. It happened so quickly.

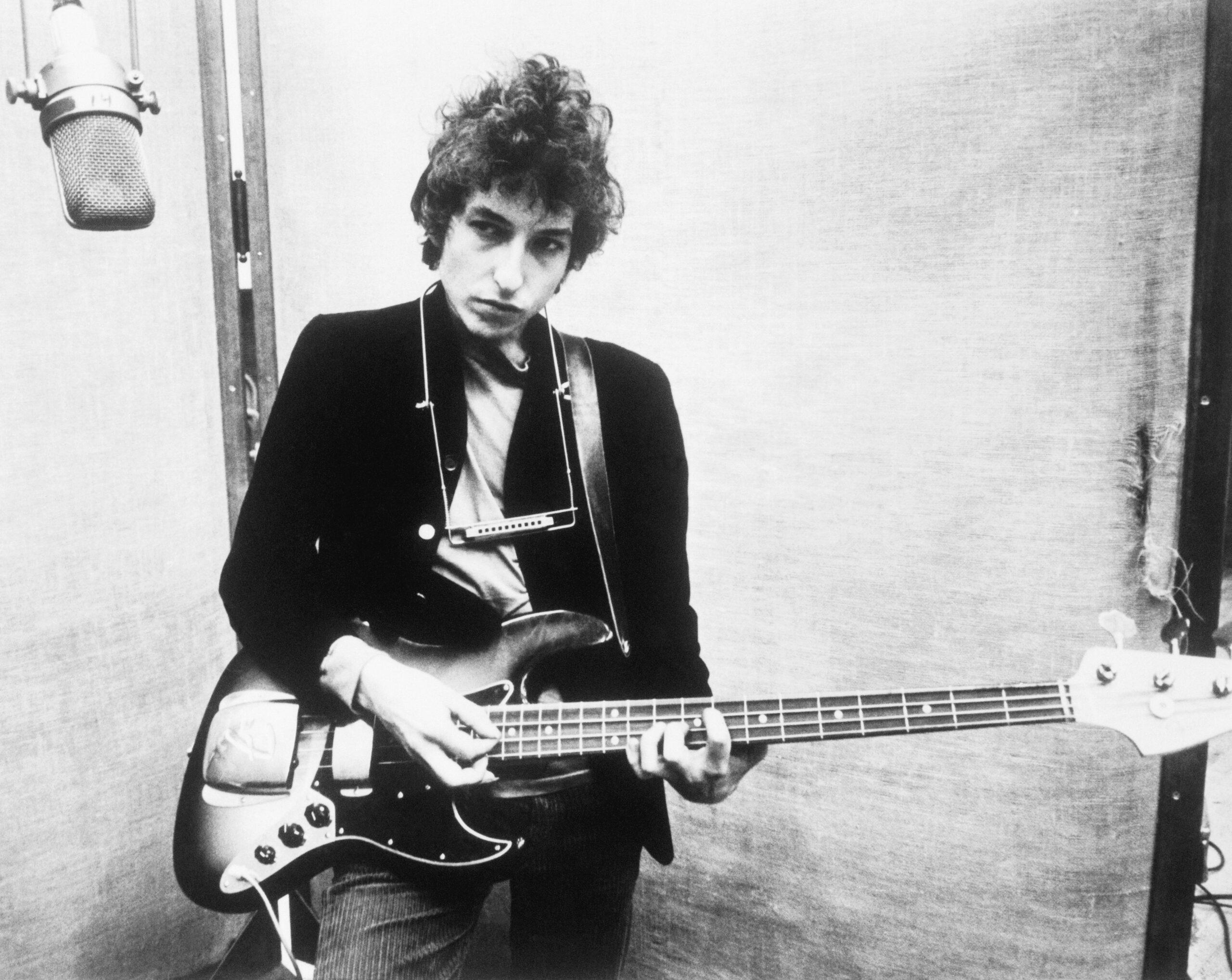

In 1967, while the actual Beatles licked an acid stamp and postmarked it c/o Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, Brian Wilson composed a teenage symphony to God, and the Velvet Underground unhooked the daisy chain linking the Summer of Love, Bob Dylan sat in a basement writing. He got there by accident. With the sun in his eyes, likely peeling around the hilly turns of Striebel Road in Woodstock, New York, near his manager Albert Grossman’s home, Dylan lost control of his Triumph motorcycle. He crashed. Prior to the 1966 accident, Dylan had released a new album approximately every eight months since 1963, a steady beat gaining volume until Blonde on Blonde, the summation of Dylan’s folk-rock fusion wracked by confusion, sadness, and new love. Despite ascending to the height of American culture, it wasn’t a happy time in his life. “Everything was wrong, the world was absurd,” Dylan wrote in his 2004 memoir, Chronicles, describing the discomfort of being hounded by fans and the press seeking meaning in his work. “The voice of a generation” had become a persistent moniker, one that Dylan despised, and still does. Guzzling amphetamines while on a tour that felt like it would never end, Dylan began to ask himself why he was playing music in the first place. The accident arrived at a time of personal waywardness, creating the freedom to exit the public eye. He took the chance, canceling tour dates and disappearing from view.

Recovering first in the third-floor bedroom of his doctor’s home and then in Hi Lo Ha, his house in Woodstock’s Byrdcliffe neighborhood, Dylan grew stronger, but hardly left his home. When he did, it was to trek to a pink shack in nearby Saugerties with some pals from his band. He spent time reading and meeting with friends like Allen Ginsberg. He grew closer to his new wife, Sara Lownds; their firstborn child, Jesse; and soon their second, Anna. And he worked, steadily. His only journey came later in the year, on a key trip to Nashville to record with local musicians. What transpired in those sessions across ’67 is one of the most significant periods in the artist’s life, about which there is little known. Gathering in New York with the members of his touring band, the Hawks, he wrote joke songs and reimagined American folk and blues. “We weren’t making a record. We were just fooling around,” Hawks leader Robbie Robertson said. In 1990, Dylan biographer Clinton Heylin wrote: “A quarter of a century on, Dylan’s motorcycle accident is still viewed as the pivot of his career. As a sudden, abrupt moment when his wheel really did explode. The great irony is that 1967 — the year after the accident — remains his most prolific year as a songwriter.” The crash has been accepted into lore as a life-altering event. It’s a genuine butterfly effect, scrutinized repeatedly for more than 50 years. For some, it marked the end of a great artist’s peak. For others, it unlocked a more mysterious and rewarding lifetime to come.

“The minute you try to grab hold of Dylan, he’s no longer where he was. He’s like a flame: If you try to hold him in your hand you’ll surely get burned. Dylan’s life of change and constant disappearances and constant transformations makes you yearn to hold him, and to nail him down. And that’s why his fan base is so obsessive, so desirous of finding the truth and the absolutes and the answers to him — things that Dylan will never provide and will only frustrate. … Dylan is difficult and mysterious and evasive and frustrating, and it only makes you identify with him all the more as he skirts identity.” — Todd Haynes

Fifteen years ago, the filmmaker Todd Haynes imagined a million Bob Dylans. Haynes thought of a line from Anthony Scaduto’s 1971 biography of the singer: “He created a new identity every step of the way in order to create identity.” This idea is sacred among Dylanologists, who categorize the songs and phases of the man by way of shorthand identifiers — Folkie Dylan, Electric Dylan, Cowboy Dylan, Divorced Dylan, et al. (This year, as part of the ongoing Bootleg Series of releases, we encountered Christian Dylan in all his glory on Trouble No More, the 13th volume, which chronicles his spiritual excursion between 1979 and 1981.) But the myriad Dylans are what make him and his work such a rich text, his matryoshka doll layers molting to reveal, well, another layer, another character. This regenerative quality makes him new again and again. Haynes took that trope of Dylanology to its logical extreme and crafted a film “inspired by” the lives of Bob Dylan, fracturing these identities into seven characters played by adults and children, men and a woman. The result is I’m Not There, an elliptical and gorgeous film that turned 10 years old this month. “I’ve heard this from other people, that he crops up in life, in times of crisis,” Haynes said before its release. Stitched into his film are not just the threads of a life we know — the image that would become the cover for 1963’s The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, a beleaguered Dylan battling the media during a press conference in 1965 — but emotional extensions about his crumbling marriage, his fetishizing of black blues and outlaws, and his vision of what the author and journalist Greil Marcus famously called “the old, weird America.”

“A biopic is always weaving these overdetermined moments with these moments we don’t know,” Haynes said in 2007. “Ray Charles at the piano, Ray Charles at home.” I’m Not There is not that. His portrait seeks to tell a story of Dylan, but never the story. What comes out the other side is a piece of art as inscrutable and redefinable as any of Dylan’s albums — a totem of a life, but never the text. There’s even a character, an actor played by Heath Ledger, who portrays a Dylanesque folk singer in a turgid Hollywood biopic speechifying about being “only a pawn in their game.” It’s Haynes’s own metacommentary about the trappings of the biopic. In each character’s story, Haynes uses a different film stock or style and a different mood to demarcate — Cate Blanchett’s wounded, cranky ’65 Dylan is shot in the style of Federico Fellini’s 8½. Ledger’s character’s story is meant to evoke the wide angles and sharp close-ups of Jean-Luc Godard. Richard Gere’s 19th-century outlaw stand-in recalls McCabe and Mrs. Miller. It’s hardly ever real, but it’s always true.

Bob Dylan has made his life an act of public obfuscation and private exhibitionism; a film that knows the difference is the only logical move. For The New York Times, A.O. Scott wrote, “It is unusual to see a masterwork emerge from one artist’s absorption with the work of another …” and yet it is clear that there is no other way to tell a life like this. After uttering the words “Bob Dylan” not once throughout the movie, I’m Not There ends with a transfixing, mournful 60-second clip of Dylan playing the harmonica before fading to black — no knots tied, no solutions found, no epilogue to speak of.

Ten years since its premiere, I’m Not There — lauded upon release — has faded from view, too. It will forever be sandwiched between Haynes’s commercial and awards-season breakthrough Far From Heaven and 2015’s Carol, confirmation of his total mastery. I’m Not There never played more than 149 theaters in America and earned less than $12 million worldwide. Like too many of Haynes’s movies, it is little seen. After a series of films about Dylan at the turn of the century, including Martin Scorsese’s 2005 documentary, No Direction Home, and Dylan’s own baffling 2003 koan Masked and Anonymous, I’m Not There is the last time anyone tried to seriously capture him on screen. He is forever unadaptable, unless he is unadapted. Imagine being Bob Dylan and watching I’m Not There. He did.

“Yeah, I thought it was all right,” Dylan said of the movie in 2012. “Do you think that the director was worried that people would understand it or not? I don’t think he cared one bit. I just think he wanted to make a good movie. I thought it looked good, and those actors were incredible.”

Of all the Dylans that Haynes renders, there is just one crucial Dylan unaccounted for in I’m Not There: 1967.

John Wesley Harding was released in the final week of 1967. It was the first America had heard from Dylan in more than 18 months. It was not at all what people expected from the voice of their generation. Dylan asked Columbia to release it with “no publicity and no hype, because this was the season of hype,” he said at the time. Columbia president Clive Davis pressed Dylan to release a single with the album, but he refused. On the much-analyzed cover, a squinting Dylan wearing a cheshire cat grin is surrounded by Luxman and Purna Das, two South Asian musicians brought to Woodstock by Grossman, and Charlie Joy, a local stonemason and carpenter. What did these men know that we don’t?

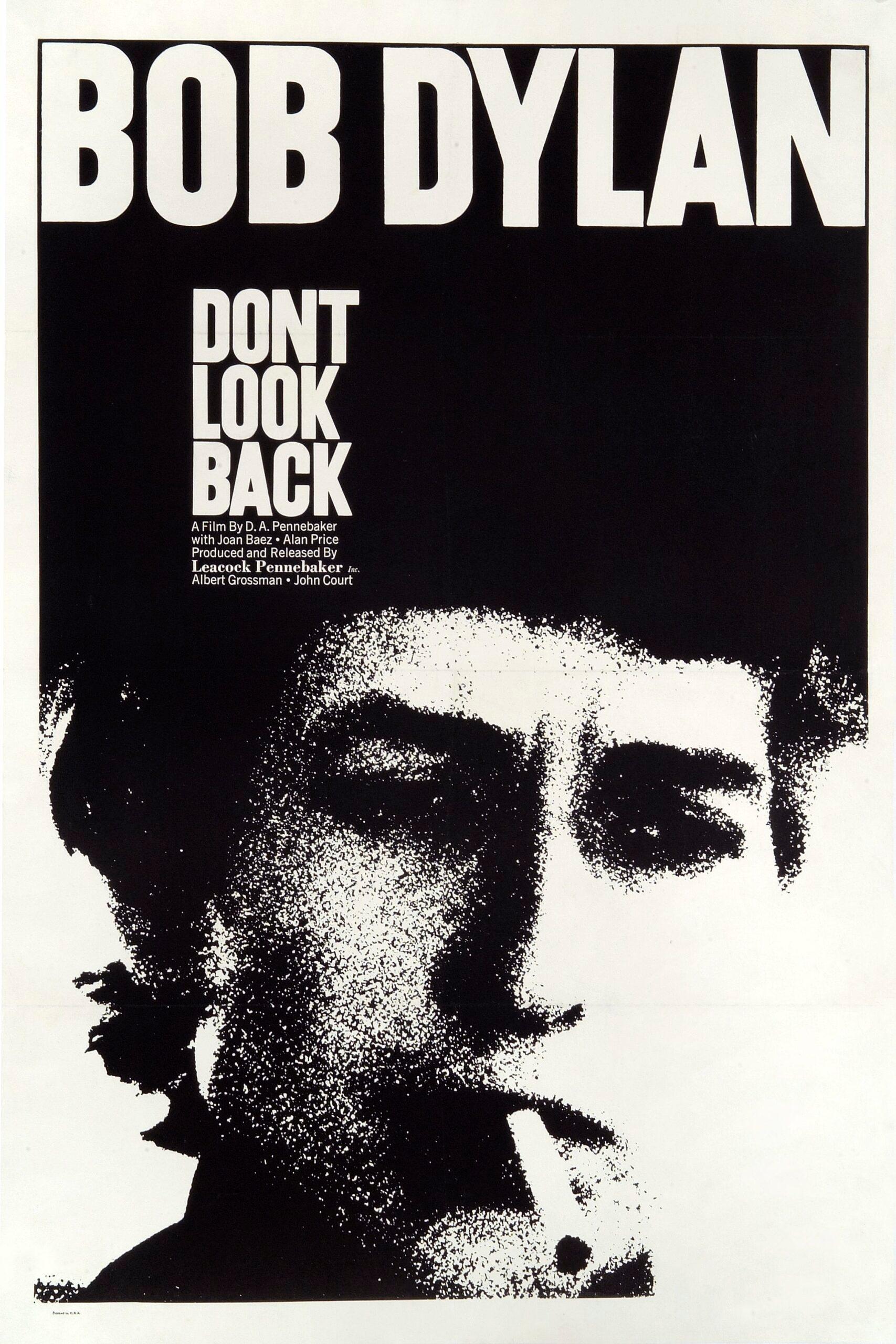

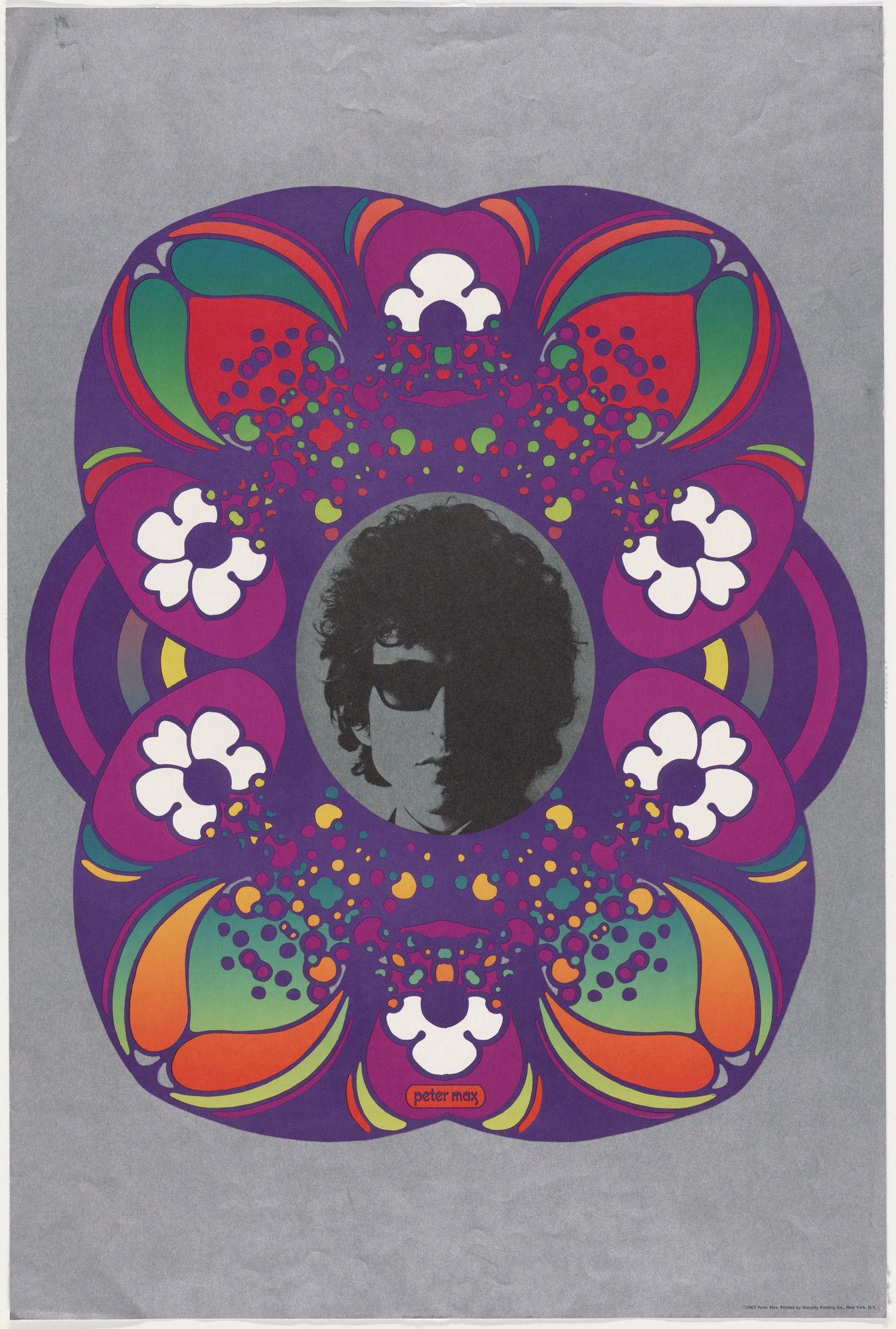

In Dylan’s absence, he had become something more than just a popular singer or a rock star. He became a proper subject. Earlier in 1967, the documentarian D. A. Pennebaker released Don’t Look Back, the first of the Dylan films, this one trailing him as he jostles with peers, the press, and his own outsize persona. Pennebaker’s camera finds a tough cookie, evasive, unsparing, and passively sarcastic. (“I’m not angry, I’m delightful,” he tells a reporter.) That same year, counterculture American artist Peter Max’s “Untitled (Bob Dylan)” was unveiled, a candy-coated, psychedelic flower burst framing a serious-looking Dylan in shades. Dylan was even set to publish a volume of poetry, circling the square of pretension. There is no modern-day analogue to Dylan’s disappearance; constant presence is the very economy of celebrity 50 years later. Taking 18 months off is to tempt the fates. For Dylan, it was a salve.

And then there was the album itself. Many didn’t quite know what to say. “He holds notes much longer now than he used to,” Ralph Gleason observed in Rolling Stone. John Wesley Harding is a plaintive record, milder in tone, largely unplugged, and more direct. It is almost entirely acoustic, a distinct departure from the ramshackle electric sounds of 1965. “Every artist in the world was in the studio trying to make the biggest-sounding record they possibly could,” producer Bob Johnston recalled. “So what does [Dylan] do? He comes to Nashville and tells me he wants to record with a bass, drum and guitar.” And unlike the sweeping emotional grandeur of “Visions of Johanna” or the moral certitude of “Masters of War,” Dylan’s eighth album has a kind of campfire quality. He’s telling stories, and we can’t always pick out the hero.

He began recording just two weeks after the passing of his hero Woody Guthrie. There are strands of Guthrie’s righteous, surefooted moral clarity in these songs. These are songs about people, draped in rectitude and clear-eyed sentiment. He commits the sin of “I,” using the first person in five of the album’s song titles. It is, in its way, straightforward. “What I’m trying to do now is not use too many words,” Dylan said in a 1968 interview. “There’s no line that you can stick your finger through, there’s no hole in any of the stanzas. There’s no blank filler. Each line has something.”

“The Ballad of Frankie Lee and Judas Priest” is at once like so many Dylan story songs that came before it — “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll” or “Ballad of Hollis Brown” — and quite different. There is something elusive about these stories; the tempo is almost jovial, but also haunted by the idea of salvation. Dylan’s notions of the spiritual always seemed literary or like tools of language to this point. But at the conclusion of “The Ballad of Frankie Lee and Judas Priest,” Dylan just comes out and says what he means, literally spelling out the song’s meaning.

Well, the moral of the story

The moral of this song

Is simply that one should never be

Where one does not belong

So when you see your neighbor carryin’ somethin’

Help him with his load

And don’t go mistaking Paradise

For that home across the road

If ever there was a biblical awakening, this is it. There are more than 60 allusions to the Bible on John Wesley Harding, a sign of things to come for Dylan. You can feel him plotting his unfamiliar course into the 1970s. Allen Ginsberg said of this time that Dylan told him, “He was writing shorter lines, with every line meaning something. He wasn’t just making up a line to go with a rhyme anymore; each line had to advance the story, bring the song forward. And from that time came some of the stuff he did with the Band — like ‘I Shall Be Released,’ some of his strong laconic ballads like ‘The Ballad of Frankie Lee and Judas Priest.’ There was to be no wasted language, no wasted breath. All the imagery was to be functional rather than ornamental.”

“Songs are in my head like they always are,” Dylan told the New York Post’s Michael Iachetta in May 1967 in the only known interview he gave during this period. “And they’re not going to get written down until some things are evened up. Not until some people come forth and make up for some of the things that have happened.” At this time, Dylan was doing battle with his manager, Albert Grossman; his record label; as well as with the idea of his own industry. He also had been thinking of his own parents, from whom he’d become estranged, as he embarked on fatherhood. Reconciliation with all parties was imminent.

John Wesley Harding may be best remembered as the album that debuted “All Along the Watchtower,” a similarly plainspoken story-song. Less than a year later, Jimi Hendrix recorded the song, cloaking it in an end-times guitar haze that recast the song as the wail of a generation’s dying idealism, moments from Nixon, trapped in Vietnam, tripping through the darkness. Dylan’s version is a lone-man’s lament. “Two riders were approaching, the wind began to howl,” he sings, before collapsing under a familiar harmonica lick.

The album was completed in three sessions in Nashville — October 17, November 6, and a polish on November 29, when he recorded the final two songs, “Down Along the Cove” and “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight,” which would point the way toward the country-infused music to come on 1969’s Nashville Skyline. Less than a month after the final session, John Wesley Harding was in stores, a remarkable turnaround time. For Crawdaddy! magazine, the critic turned eventual Bruce Springsteen manager Jon Landau wrote, “For an album of this kind to be released amidst Sgt. Pepper, Their Satanic Majesties Request, After Bathing at Baxter’s, somebody must have had a lot of confidence in what he was doing. … Dylan seems to feel no need to respond to the predominant trends in pop music at all. And he is the only major pop artist about whom this can be said.”

John Wesley Harding has neither the iconic bearing of the albums that preceded it, nor the fascination with the noble failures that would follow, before Dylan reclaimed his standing at the center of popular music in the mid-’70s. It is a transition, a signal from an artist pivoting, away from iconography to something more earthbound. But unlike the self-conscious “stripped down” records that many artists would use to vanquish the sins of their past lives, Dylan’s had an eccentric affect — like he’d stumbled into it by accident. Which, in a way, he did.

Of course, John Wesley Harding isn’t the most memorable set of recordings Bob Dylan made in 1967. In June, in the basement of that Saugerties house that would come to be known as the Big Pink, Dylan began working with Robertson, Garth Hudson, Richard Manuel, and Rick Danko on something more ecstatic. “That’s really the way to do a recording — in a peaceful, relaxed setting — in somebody’s basement,” Dylan told Jann Wenner in 1969. “With the windows open … and a dog lying on the floor.”

Hudson, a sonic engineering wizard, used two stereo mixers and a tape recorder to capture a unique racket. “‘The Basement Tapes’ are a testing and a discovery of roots and memory,” Greil Marcus wrote in the album’s liner notes. “… [They are] no more likely to fade than Elvis Presley’s ‘Mystery Train’ or Robert Johnson’s ‘Love in Vain.’” It is what happens when traditional American music played by a mischievous troubadour on the mend meets a gang of Canadian rip-cord pullers. What happened in between is in the pages of Marcus’s essential book, The Old, Weird America: The World of Bob Dylan’s Basement Tapes, which interprets the music on The Basement Tapes like the dead sea scrolls or transmissions from the wind, carrying 100 years of sound in its songs. It is a stone classic of American criticism and an interrogation of the mythology that surrounds art. Even Dylan was impressed, and he doesn’t like much about his own mythology.

The songs are all over the place, literally, from the fields of Mississippi to the beaches of Acapulco, and in feeling, too, by turns lighthearted (“Yea! Heavy and a Bottle of Bread”) to gutted (“Tears of Rage”) to apocalyptic (“This Wheel’s on Fire”). Half of what we hear is the sound of friends screwing around. The version of the album that was eventually released in 1975 opens with a song that is literally called “Odds and Ends.” Loopy, self-mocking songs like “Clothes Line Saga” sit alongside some of the fiercest compositions of his career. It closes with the other thematic stripe, on “This Wheel’s on Fire,” a pairing of Dylan and Danko that rivals any song either ever wrote or sang.

“We were doing seven, eight, 10, sometimes 15 songs a day,” Garth Hudson once said. “Some were old ballads and traditional songs … but others Bob would make up as he went along. … We’d play the melody, he’d sing a few words he’d written, and then make up some more, or else just mouth sounds or even syllables as he went along. It’s a pretty good way to write songs.”

More than 100 songs were put to tape during this period — covers, originals, reinterpretations, and curios. The sessions’ recording style makes every song sound as though it were made at the bottom of a drained river basin, inside the hull of a rotting tugboat. If John Wesley Harding was stripped down, The Basement Tapes are washed out, the sounds of what happens when nobody is looking. It’s the session that birthed “Quinn the Eskimo (The Mighty Quinn)” and “I Shall Be Released.” It contained multitudes.

But they weren’t intended for consumption, at least not officially. The recordings became the first bootleg with a makeshift cult. Wenner wrote in the pages of Rolling Stone that the Basement Tapes should be released as an album of its own. Separate illegally produced compilations, one in ’68 and another in ’69, stoked the appetite of fans. And then nothing. A contractual dispute held the music in limbo for six more years, until Columbia bundled 16 songs from the sessions with eight more songs by the Hawks, since rechristened the Band after their experience with Dylan, to release 1975’s The Basement Tapes. The eight years that had passed since it was recorded gave the music a feeling that was even more ancient than in its conception. It felt like the old world because it was in fact from the old world. Earlier that year, Dylan had released the searing, triumphant Blood on the Tracks, reaffirming his place as a major artist. Robert Christgau, writing for The Village Voice, noted no shame in awarding The Basement Tapes its highest honor: “We don’t have to bow our heads in shame because this is the best album of 1975. It would have been the best album of 1967, too.” Eventually, the world would hear those 100-plus songs, when a box set was released in 2014.

Though Haynes refrained from portraying the madcap sessions in the basement in Big Pink, nor the trips down to Nashville to record John Wesley Harding, he did grab a song from The Basement Tapes for the soundtrack to I’m Not There. Jim James, the lead singer of My Morning Jacket, covers “Goin’ to Acapulco” with Calexico and is featured in the film. Haynes transforms Dylan’s bandit anthem into a funeral dirge for a young girl killed by developers’ dreams of an industrial America — a resident of the old, weird America cast aside by a world hurtling toward progress. Haynes shows us the residents of Riddle, Missouri, their faces covered in paint and masks, costumed and unable to look away from the dead girl on the grandstand and the band playing tribute to her. These are bereft citizens of a place that never existed, stand-ins for the world that Dylan created on The Basement Tapes and John Wesley Harding. The last vestiges of a time Bob Dylan never even knew.

Dylan played at Woody Guthrie’s memorial concert in 1968 and then largely vanished from view again. “One day I was half-stepping, and the lights went out,” he would later say. “And since that point, I more or less had amnesia. … It took me a long time to get to do consciously what I used to be able to do unconsciously.” He was just 25 years old when the lights went out. Twice that lifespan has since passed, and we still don’t really know what happened in 1967, other than what we can still hear.