On December 20, 1986, one month after the release of Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home, William Shatner hosted Saturday Night Live. By that point, the actor had been playing Captain Kirk for 20 years. More than anyone else (except maybe Leonard Nimoy), he understood what it was like to live under a discerning subculture’s microscope.

Knowing this, Robert Smigel approached Shatner early in the week with an idea. The writer, who was in the middle of his second season at SNL, pitched a sketch in which the sci-fi icon visits a Star Trek convention. The twist? Instead of warmly greeting the attendees, he’d make fun of them. What sold him on the scenario were three words that Smigel suggested he say to the mostly bespectacled crowd: “Get a life!”

“That’s what made him laugh,” Smigel said. The phrase wasn’t yet the ubiquitous insult lobbed at know-it-alls, but he’d heard it before. Smigel, whose lengthy SNL résumé includes the creation of both the long-running, oft-quoted “Bill Swerski’s Super Fans” and the animated short series TV Funhouse, went as far as calling Shatner’s dork roast “maybe the most resonant sketch I ever wrote there.”

The world never used to care about the opinions of nerds. For decades, fanboys and fangirls weren’t considered important enough to acknowledge, let alone listen to. Then things changed. It’s hard to determine exactly when the flip occurred, but the SNL sketch signaled an impending mainstream shift.

The six-minute segment endures because of what it’s poking: the strange relationship between the diehards and the people behind their favorite television shows and movies. In those days, it was one-sided. Hardcore fans held little sway. Now, emboldened by the internet and their own purchasing power, they’ve gained leverage. As former SNL staffer Jon Vitti, who helped Smigel with the Star Trek sketch, put it: “You’re not really picking on the weak anymore.”

In 2018, fan-spurred conflict has grown exhaustingly intense. Consider: Seven weeks after The Last Jedi premiered to critical acclaim, the Rotten Tomatoes audience score sits at 48 percent. (Alt-right trolls naturally took credit for that dip.) A Change.org petition demanding that Disney “strike Star Wars Episode VIII from the official canon” has more than 95,000 signatures. Several interviews that Mark Hamill gave about his initial dislike of Luke Skywalker’s character arc have been employed to cudgel the blockbuster. And in January, a nauseatingly opportunistic misogynist made and uploaded a “de-feminized” edit of the film to the torrent site The Pirate Bay.

Director Rian Johnson has handled the increasingly toxic backlash with the kind of self-aware openness that only a Star Wars fanatic could possess. While refusing to renounce his vision of the franchise, he’s taken to Twitter to engage detractors. That Johnson is able to stay civil is admirable. But blasters don’t always have to be set for stun. Occasionally, a full-on excoriation can be cathartic.

The 1986–87 season of Saturday Night Live was an important one in the history of the show. The year prior, series creator Lorne Michaels had returned after an extended hiatus. Following a disastrous 1985–86 campaign that raised the threat of cancellation, he fired most of the cast. The producer kept Nora Dunn, Jon Lovitz, and Dennis Miller, and brought on new cast members Dana Carvey, Jan Hooks, Phil Hartman, Victoria Jackson, and Kevin Nealon.

With a bunch of all-time-great SNL performers to write for, Smigel found his groove. In late fall, he devised a funny, well-received sketch featuring Hartman as a much-sharper-than-he-looks version of Ronald Reagan. “Mastermind” played off a question that some Americans were then asking: Beneath his charming façade, was their septuagenarian president still competent? William Shatner obviously wasn’t the subject of that kind of speculation, but he, too, had a well-polished public persona. When the actor arrived at 30 Rock to prepare for his hosting gig, Smigel presented him with an idea that scrubbed off his detached, respectful veneer. That cleanse allowed viewers to see what the (only slightly) fictionalized version of the man behind Captain Kirk really thought of his most dedicated fans.

The star liked the pitch, but there was a small problem: Smigel wasn’t much of a Star Trek fan. Luckily, Jon Vitti was. He’d seen every episode of the original series multiple times. Shatner was one of his childhood heroes. “There is no star as big as a star from when you were a kid,” said Vitti. He geeked out over meeting Shatner, just as he did later when Adam West appeared as himself in a Simpsons episode that Vitti wrote.

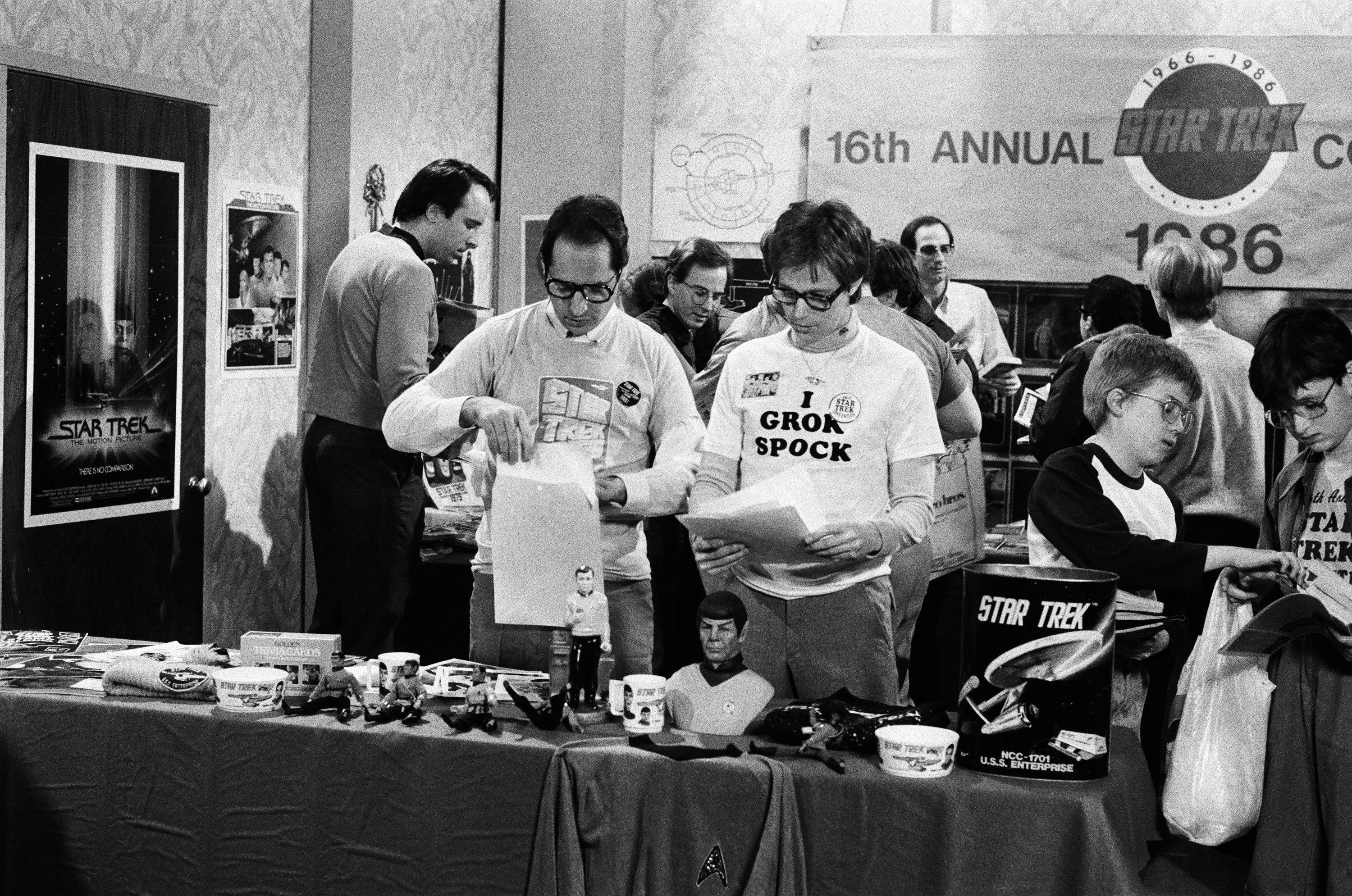

Smigel and Vitti, both in their 20s at the time, spent the Tuesday night of Shatner’s week in New York working on the sketch. Vitti’s familiarity with the source material came in handy. He offered up obscure Star Trek details and made sure that the convention sign the audience sees read “Welcome Trekkers,” the term devotees prefer over the pejorative “Trekkies.”

“If it happened today,” Vitti said, “Robert probably would have gone on the internet, picked up the references he needed, and written it himself.” Smigel’s goal was to mock fans’ fascination with minutiae rather than ridicule their physical appearance. “I remember actually asking wardrobe to tone it down a little bit,” he said. “A few less pocket protectors, if possible.” Carvey’s character does end up in an “I Grok Spock” T-shirt, Nealon’s wears a Starfleet uniform, and Lovitz sports a pair of Vulcan ears. Smigel conceded that “they probably came off fairly stereotypical.”

The scene built up to Shatner’s rant. “The whole sketch was written around that moment,” Smigel said. When it was time to come up with the tirade, Smigel consulted George Meyer. Before becoming one of the best Simpsons writers ever, he toiled at SNL. Meyer had the rare ability to transform a hilarious idea into something transcendent. “He could drop three lines in the script,” said Vitti, who also became a prolific Simpsons writer, “and those were the three lines people talked about.” A Meyer gem that made it into Shatner’s diatribe: “You’ve turned an enjoyable little job, that I did as a lark for a few years, into a colossal waste of time!”

After a production assistant passed Smigel and Vitti a typed copy of their sketch, they panicked. While writing it longhand on a legal pad, neither realized how long it had run. Short, unfunny sketches were dismissed and quickly forgotten. But if an overdone dud made it to the episode read-through in the writers’ room, Vitti said, “you could feel the hate.” He recalled even asking coordinating producer Audrey Peart Dickman to pull the sketch before that could happen. But, Vitti said, she calmly told him that it was too late.

It was a wise decision. The sketch got laughs at the read-through and was scheduled to run in a prime slot: right after the monologue. It went well at dress rehearsal, but Smigel thought Shatner hadn’t fully committed to the resentfulness of his role. “Shatner was playing it a teeny-weeny bit jokey,” Vitti said. So before the live taping, the laid-back Smigel gave Shatner a note.

“I was pretty fearless back then about talking to actors if I was certain it would help the end result,” Smigel said. “Life had not yet beaten me down enough to suggest that some fights aren’t worth fighting.” The writer said he asked Shatner to “play it more serious.” In other words: ratchet up the on-screen vitriol.

It wasn’t an easy task for a man who in real life didn’t want to alienate the fans who adored him. In fact, in his monologue Shatner addressed Star Trek aficionados. “I mean they’re truly incredible,” he said, “and I hope they have a sense of humor about the show tonight. Or I’m in deep trouble.”

Playing a comedic version of yourself isn’t easy, but Shatner pulled it off. He even seemed to take Smigel’s advice. When conventioneers ask him to recite the combination of a safe in a particular Star Trek episode and to confirm the number of saddlebred horses he has on his farm, he stops them.

“Before I answer any more questions, there’s something I wanted to say,” he announces from a podium. “Having received all your letters over the years, and I’ve spoken to many of you, and some of you have traveled, you know, hundreds of miles to be here, I’d just like to say … get a life, will you, people?! I mean, for crying out loud, it’s just a TV show!”

Soon Shatner asks Lovitz’s character if he’s ever kissed a girl and continues, “There’s a whole world out there! When I was your age, I didn’t watch television! I lived! So move out of your parents’ basements” — bloggers may have Smigel to blame for the spread of that dig — “and get your own apartments and grow the hell up! I mean, it’s just a TV show, dammit. It’s just a TV show!”

When he finishes his broadside, Shatner leaves the dais only to be met by Hartman’s angry emcee. The two shove each other, Hartman waves Shatner’s contract in front of him, and then the actor returns to the stage, licks his lips, and says in his unique cadence, “Of course that speech was a re-creation of the Evil Captain Kirk … from … um … Episode … um … 37 … called ‘The Enemy Within.’ So thank you and … live long and prosper.”

The clever ending still throws Vitti. After all, “The Enemy Within” was the fifth episode of Star Trek, not the 37th. Minor error aside, the sketch was a hit. The same night, Shatner opened a Star Trek–themed restaurant in a sketch and for another bit resurrected another old role: T.J. Hooker.

In the late 1990s, the actor wrote a memoir centering on his quest to finally embrace the fans with whom he hadn’t truly ever personally connected. In reality, his turn as nerd-bashing Evil Kirk on SNL wasn’t exactly a put-on.

“Were they sane?” writes Shatner, who through a spokesperson declined to be interviewed for this article. “Were they sober? Did they really need to ‘Get a life’? To be brutally, humiliatingly honest, that now-infamous Saturday Night Live sketch was for me, at that time, equal parts comedy and catharsis. I was oblivious to the facts. I bought into the ‘Trekkie’ stereotypes. In a nutshell, I was a dope.”

Shatner called the book Get a Life! In it, he credits the writers of the sketch that inspired the title: Judd Apatow and Bob Odenkirk. The misattribution still makes Smigel smile. “How,” he said, “could he get it that wrong?”

Smigel wasn’t done playfully messing with nerds. “It’s been a lifelong pursuit,” he deadpanned. In 1993, the self-proclaimed Saturday Night Live nerd became the first head writer of Late Night With Conan O’Brien. Four years later, Triumph the Insult Comic Dog, the cigar-chewing, Smigel-voiced puppet, made his show debut. In 2002, the foul-mouthed canine famously sniffed around the premiere of Attack of the Clones. At one point, the pooch looks at the many buttons on someone’s Darth Vader suit and asks, “Which one of these calls your parents to pick you up?”

As it turns out, a bunch of costumed Star Wars fans didn’t mind Triumph berating them. “There’s a big overlap between nerds and comedy nerds,” Smigel said. “This was the first time that I had done Triumph where I was sort of surrounded by people who found Triumph really funny.”

In 2008, Smigel brought Triumph to the San Diego Comic-Con. “Nerds. Dorks. Geeks. Mouth-breathers. Loners. Mama’s boys. Noobs. Droids. Druids. Trekkies,” he began a long panel speech. But after thoroughly ripping the audience, he acknowledged — in the most predictably offensive way possible — the power that geeks now wield. “Move over, Jews, the nerds control the media,” said Triumph, whose owner is indeed a Member of the Tribe. “Praise to the nerds.”

Tasteless joke aside, he was right about nerds. They finally had a say. “The explosion of the media and the internet have definitely empowered the quote-unquote nerd,” said Smigel, who knows this from experience. In the early 2000s he was asked to write a comedic Green Lantern script. Warner Bros. envisioned Jack Black as the star. But when Smigel’s draft leaked online, fans revolted. Then the studio went in a … different direction.

“Advertising and the opinion of your local critic used to basically dictate how people responded to the idea of a movie,” Smigel said. “And now it’s so democratic that everybody’s opinion can be heard fairly equally. You can just go to IMDb and read 1,000 opinions.”

On the surface, that sounds nice. But among those mostly innocuous opinions are extremes. Those tend to be amplified. Just look at the ongoing bickering about The Last Jedi. The nasty trolls making noise now are nothing like the gentle Trekkers in the “Get a life!” sketch, which these days would have much more deserving targets.

Smigel, however, doesn’t think a similar premise would induce nearly as many laughs now as it did originally. “I wouldn’t have even thought to write it,” he said. “Anything that reeks of obsession is still funny but it’s certainly not as foreign as it used to be.”

While Shatner was delivering his cathartic rant back in 1986, Smigel decided to do something that he normally didn’t: He stood right next to Lorne Michaels. When the audience applauded, he made eye contact with his legendarily reserved boss. “I remember us sharing a look,” Smigel said. “Just contained excitement.”