In 1989, when Oakland Athletics outfielder Billy Beane was making the final few outs that lowered his ultimate career big-league on-base percentage to .246, a California baseball team was already winning with the ideas that would one day lead to Brad Pitt playing Beane on the big screen. This proto-Moneyball movement took place in the obscure, semipro, and now-defunct Sacramento Valley Baseball League, which explains why it didn’t beget a bestseller or an Aaron Sorkin screenplay. The story’s star, on the surface, was a 22-year-old college kid named Gary Huckabay, an SVBL player-manager who several years later would found Baseball Prospectus, the publication that would help pioneer and popularize the data-driven analysis of sports.

“I would wonder why we would have all these great ballplayers and we would go 8-15,” Huckabay says by phone. “Because clearly it couldn’t be my brilliant leadership. It had to be something else.” Maybe, Huckabay decided, his players weren’t good enough at getting on base. So he embraced the same strategy that Beane would employ as A’s general manager a decade later: He recruited players who took a lot of walks, a skill that the market (such as it was in the SVBL) didn’t value. “At this time, that was a derogatory thing,” Huckabay says. “It was considered, like, ‘Don’t play lawyer ball, get up there and swing the bat.’ Which is another way of saying, ‘Go up there and make some outs.’”

Huckabay’s newly patient late-’80s SVBL rosters outplayed his old squads, so he extended the same approach to his softball league. “We ended up with the same reputation in softball, as being a bunch of weasels who drew walks and didn’t swing the bat and couldn’t play,” Huckabay recalls. “And you’d look up and we’d be ... 8-1, or finishing third in a tournament of 200 teams. So it was really a tangible and palpable [improvement].”

To this point, the story sounds the same as so many other underdog sports narratives of the analytics age: Iconoclastic outsider gets bold idea, puts bold idea into practice, weathers barbs from macho traditionalists, and wins while the Luddites look on in dismay. But this particular tale has a twist: The heroes of most of those stories are men; the hero of this one is a woman who was born 18 days after Beane and beat him to the base-on-balls epiphany but didn’t make it into Moneyball. Her name is Sherri Nichols, and she inspired Huckabay’s onslaught of walks.

Huckabay, it turns out, wasn’t sure drawing walks was a skill hitters could have until Nichols, an online acquaintance, convinced him. “My view of her originally was rather Neanderthal,” Huckabay says. “It was, ‘What the hell can you possibly know, you haven’t played the game,’ etc. And I had some pretty strong opinions, and she basically was very patient and very well-researched and very well-put-together, and simply dissected a lot of my misperceptions one by one. Much to my advantage, because I ended up playing better ball because of it.”

Nichols never knew that her words were reshaping the roster of an amateur team across the country; that was just one of many unanticipated ripple effects that flowed from her keyboard. “I did enjoy debating people who weren’t sabermetric fans,” she recalls. “I think I did change some people’s minds.”

Helping Huckabay’s amateur teams was the least of Nichols’s contributions to baseball. Though she’s all but unknown among modern, stat-savvy fans, Nichols was an influential figure at a formative time for sabermetrics. The precedent-setting research she did during the late ’80s and early ’90s, and the deep impressions she made on her colleagues, left a legacy that’s still felt today at the highest levels of the sport. And she made that mark despite being an outsider among outsiders, the one woman in an intellectual field every bit as male-skewed as the grass one where Beane was winding down his career. “I know how hard it is to be in a field where there’s nobody like you,” Nichols says. “It’s a constant subtle message that maybe you don’t belong, that when you screw up maybe it’s more than just a mistake.”

Nichols’s career holds a special significance in light of sabermetrics’ homogenous history. On an off day during the New York Yankees’ championship run in October 2009, another then-intern for the team, Alex Rubin, and I passed a slow afternoon at the stadium in the nerdiest way imaginable: by creating a Sporcle quiz about the inventors of sabermetric statistics. Gchatting arcane names and acronyms across the small room where the other interns and we sat, we assembled a list of 60 sabermetric stats and the people who’d published them. In a nod to late-aughts stathead humor, we also included a couple of hidden answers that poked fun at a pair of ESPN advanced-stat disparagers, Buster Olney (“Productive Out Percentage”) and Joe Morgan (“computer numbers”). Had we undertaken our task a little later, we surely would have found room for another then-ESPN pundit’s senseless Frankenstein stat, OPSBI.

It didn’t dawn on either of us at the time, but the inventors we’d identified had something in common: They were all men. We’d traced baseball’s statistical lineage over a span of several decades, from Allan Roth to Bill James to Tom Tango, and in sketching out that whole history, we hadn’t included one woman.

She was actually kind of a queen-bee, authoritarian voice. People didn’t mess with Sherri too often, simply because she was usually right.Gary Huckabay, Baseball Prospectus founder

Although no current baseball bylaw prohibits female players, no woman has ever played in the majors or the affiliated minor leagues. Because broadcasters, scouts, and other front-office executives have historically tended to be pulled from the ranks of former players, the all-male makeup of MLB rosters has flowed from the field to most other areas of the league. It’s still newsworthy when a woman is hired as a scout, a scouting coordinator, a member of a field staff, an umpire, or a play-by-play person, or when a team hosts an in-ballpark event that celebrates women in baseball instead of condescending to them. Notably, no major league team has hired a female GM. Of course, the gender bias begins long before the big leagues, in youth sports, where girls are often funneled from baseball to softball (assuming they’re not discouraged from participating at all).

Sabermetrics, then, isn’t alone in its lack of gender diversity, both in baseball and in related non-sports fields; women are widely underrepresented in many STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) occupations. But while in some ways it may not be surprising that sabermetrics would be such a boys’ club, in others it’s more glaring because the statistical side of the game is an area where on-field experience is less common and where critical thinkers who lack traditional baseball backgrounds have been the dominant demographic. Before breaking into baseball, Roth was a salesman; James, a night watchman; Tango, a computer programmer. Yet even in an eclectic community whose leading lights came to the game from a multitude of starting points, Nichols was unique.

Nichols, now 55, grew up in Clarksville, Tennessee, roughly equidistant from Atlanta, St. Louis, and Cincinnati. A lifelong sports fan, she embraced baseball early on as a means of bonding with her father, rooting for the then-dynastic Reds. Math, at which she always excelled, was another early love. She earned her undergrad degree in physics at Tennessee Tech and went to grad school for computer science at Carnegie Mellon in Pittsburgh, where the Pirates became her adopted team.

While at CMU in the mid-’80s, she enjoyed access to Usenet, a collection of bulletin-board-like newsgroups that functioned as the precursors to today’s internet forums. There, she stumbled across rec.sport.baseball, a hotbed of baseball analysis populated largely by a forward-thinking fringe influenced by James, whose annual Baseball Abstracts were then nearing the end of their run. The newsgroup’s threaded discussions were a breeding ground for future prominent writers (such as ESPN’s Dan Szymborski) and team employees (such as Cleveland Indians principal data scientist Keith Woolner), as well as the place where many milestone discoveries—including Woolner’s work on Value Over Replacement Player (VORP) and Voros McCracken’s paradigm-altering findings about defense-independent pitching—received their first informal peer reviews. It was also the primordial soup from which Baseball Prospectus sprang, when in 1995 Huckabay invited four other rec.sport.baseball standouts—Clay Davenport, Joe Sheehan, Ringer contributor Rany Jazayerli, and Christina (then Chris) Kahrl—to band together and produce the book that became Baseball Prospectus 1996, the first edition in a still-running annual series.

Nichols and her husband, David, whom she met at CMU, had been introduced to the Abstracts through a friend of David’s, so r.s.b. was a welcome environment, full of like-minded thinkers who were still very much in the minority among fans. “This was still the days when most people focused on batting average and RBIs,” Nichols recalls by phone. “There was a group of us that had noticed the importance of on-base percentage and the effects of park effects, and lineup effects on RBIs, and stuff like that—and then the people who called us stats-drunk computer nerds” (which r.s.b. regulars often abbreviated as “SDCN”).

Nichols’s affinity for math, coupled with her literate and irreverent but no-nonsense communication style, made her a perfect fit for the r.s.b. board. “She’s good at seeing patterns and noticing correlations; she has a [broad] set of interests and education ... and she can write,” David Nichols says via email. After Sherri discovered the nascent community, she gradually started spending more and more time there. “Since I was in grad school, it was an easy way to avoid doing stuff that was driving me nuts,” she says.

Although Nichols’s Jamesian philosophies fit in seamlessly with the r.s.b. ethos, her name still stood out. “I was pretty much an outlier,” Nichols says. “I can’t really remember any other women.” While r.s.b. wasn’t a toxic environment by internet standards, it wasn’t without its discriminatory and exclusionary behavior. “There was definitely that kind of latent [sexism],” Huckabay says. “Even if it wasn’t spoken, it was out there as prominently as racism or anything else.” Nichols encountered occasional disparaging remarks like “You need to get a boyfriend,” although she remembers that kind of comment being more common on rec.sport.hockey, where posters weren’t as quick to come to her defense.

Between her degree in physics, her time spent studying computer science—a field from which women, who were always outnumbered by men, had by the mid-’80s begun a mass exodus—and, after leaving school, her 1990-95 programming job at the Silicon Valley software designer Adobe, Nichols always moved in mostly male circles. “I was used to being an outlier,” Nichols says. Her husband adds, “None of that is easy for a woman, but she’s always been able to navigate her way through.”

More than 20 years after Nichols stopped posting in the group, those who frequented it at the time speak of her status at r.s.b. in appreciative (bordering on reverent) tones. “She was actually kind of a queen-bee, authoritarian voice,” Huckabay remembers. “People didn’t mess with Sherri too often, simply because she was usually right. And she was really influential on me personally. I can’t speak for others, but I got the impression that she was a real opinion and thought leader.” In Huckabay’s foreword to BP96, Nichols was the first person he thanked after the four cofounders who’d helped him write the book. “Sherri has taught me more about baseball than anyone else in the entire world,” he wrote.

The other BP cofounders echo Huckabay’s account. “The respect she commanded and had earned was impressive,” Kahrl, now a senior MLB editor at ESPN, says via email. “When Sherri weighed in, it was a blend of quantitative analysis peppered with a few dry whip-smart cracks that was pure pwnage. If the guiding ethic of r.s.b. was to not suffer fools gladly, Sherri was one of the guiding lights who inculcated that virtue without malice, and with a reliably thoughtful commitment to asking questions and getting answers.”

One of Nichols’s coinages from the r.s.b. days is still sometimes cited today. In catcher Mickey Tettleton’s early days with the A’s, he was a so-so hitter, posting a 91 OPS+ over four seasons. When he went to Baltimore in 1988, he became one of baseball’s best-hitting backstops, recording a 128 OPS+ over three seasons and winning a Silver Slugger Award in 1989. Nichols noticed that Tettleton, who had been regarded as a great defensive catcher in Oakland, was suddenly being described as a bad defensive catcher in Baltimore. “I’m going, ‘Wait a minute, this is the same guy,’” Nichols says. “And then I observed many times, catchers who couldn’t hit had this reputation of being great defensive catchers, but catchers who could hit, unless they were Johnny Bench, were assumed to be bad defensive catchers.” The result was Nichols’s Law of Catcher Defense: A catcher’s defensive reputation is inversely proportional to his offensive abilities. The observation was Nichols to a T: witty, perceptive, and unafraid to challenge illogical prevailing opinions.

Just by being a visible and admired member of r.s.b. from the ’80s to the mid-’90s, Nichols helped open minds. Jazayerli discovered the sabermetric community after spending his childhood enmeshed in a series of subcultures that were, in his personal experience, entirely male-dominated: video games, science fiction, and Dungeons & Dragons. “I didn’t grow up in Hawkins,” he says via email. “I never met a Mad Max.” Nichols was the first woman he’d encountered who was equally passionate about one of his niche, nerdy interests. “It sounds kind of weird and maybe even a little chauvinistic to say that I was floored by the fact that a woman geeked out about baseball as much as I did, when you now have dozens of terrific female baseball writers,” he says. “But that was the world online in the mid-1990s. To the extent that Sherri made it seem perfectly normal to me for a woman to care about baseball as much as I did and see the game through the same lens, if she made it a little bit easier for [other women] to get through the door, [that] deserves to be remembered.”

I didn’t understand my own power, and the power of women working together.Sherri Nichols

It’s easy to imagine a dramatically different alternate history in which Nichols never joined r.s.b. It’s a baseball butterfly effect: Without Nichols, Huckabay might not have seen the sabermetric light. Without Huckabay’s conversion, Baseball Prospectus might never have formed. And without Baseball Prospectus—whose alumni litter front offices, whose analysis has reshaped the game, and whose brand of acerbic, highly literate, and, frankly, Nicholsesque commentary has hastened the acceptance of stats among media members and consumers not just in the sports ecosystem but across the culture at large—the world wouldn’t look quite the same. But Nichols’s indirect influence through others is only half of her story. She also shaped the future of sabermetrics herself.

In October 1983, Bill James proposed Project Scoresheet, a crowdsourced campaign to record previously unavailable play-by-play (and later, pitch-by-pitch) information about baseball games. When the nationwide effort got off the ground the following season, both Sherri and David volunteered to assist the Pittsburgh chapter with scoring, computer input, and recruitment. David, along with future Red Sox senior baseball analyst Tom Tippett, later wrote the software that streamlined the process of entering and analyzing the data, and Sherri wrote for a Project Scoresheet book series called Bill James Presents the Great American Baseball Stat Book, which was published in 1987 and 1988.

“The Nicholses together were quite a force of nature inside the project, because they’re both very smart, both very articulate, both have strong opinions and are willing to assert them,” writer, editor, and statistician Gary Gillette, who served as one of Project Scoresheet’s executive directors, says via phone. “No one would think anything odd about that for a man, but because Sherri was a woman, people sat up and took notice.”

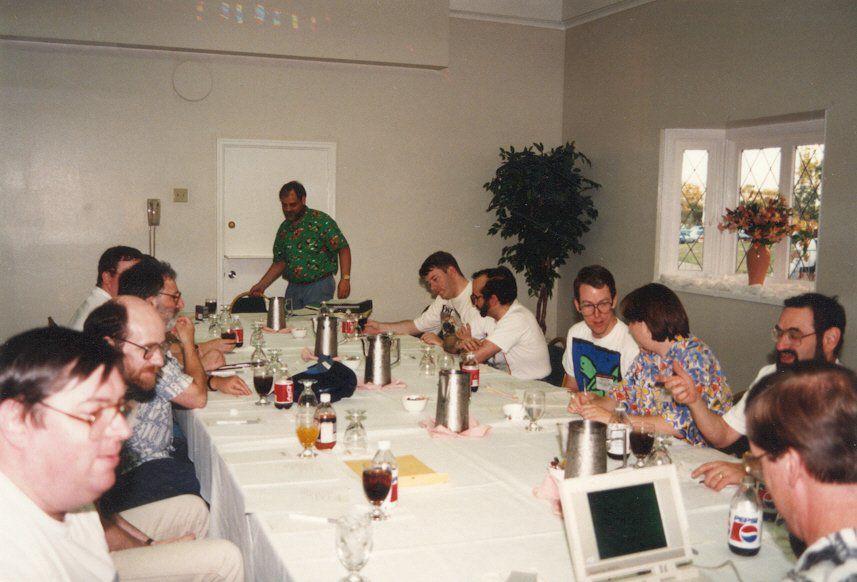

Working on Project Scoresheet led the Nicholses to start attending annual conventions hosted by the Society for American Baseball Research, or SABR (the acronym from which “sabermetrics” is derived). Like rec.sport.baseball, SABR was overwhelmingly male. According to the organization’s director of editorial content, Jacob Pomrenke, SABR’s membership from the mid-1980s through the mid-2000s was 90-95 percent male. (That figure has fallen slightly to about 85 percent today.)

Although Nichols wasn’t the only woman in SABR or Project Scoresheet, her training and research interests drew attention. “Having a woman who was an active participant, who had strong opinions, who could argue, who would hold her own with the men and even, in fact, beat the crap out of them analytically, and who wasn’t passive or didn’t defer to the guys was unusual,” Gillette says. “And people were very aware of that.” Gillette was still a fairly new SABR member when he went to the 1986 convention in Chicago, which the Nicholses also attended. “I remember hanging around with Bill James and [STATS Inc. and Baseball Info Solutions CEO] John Dewan and other people,” Gillette says. “Sherri was talked about frequently, partly because of her work, her ability to analyze stuff, etc., partly because it was just unusual to have a woman doing that stuff.”

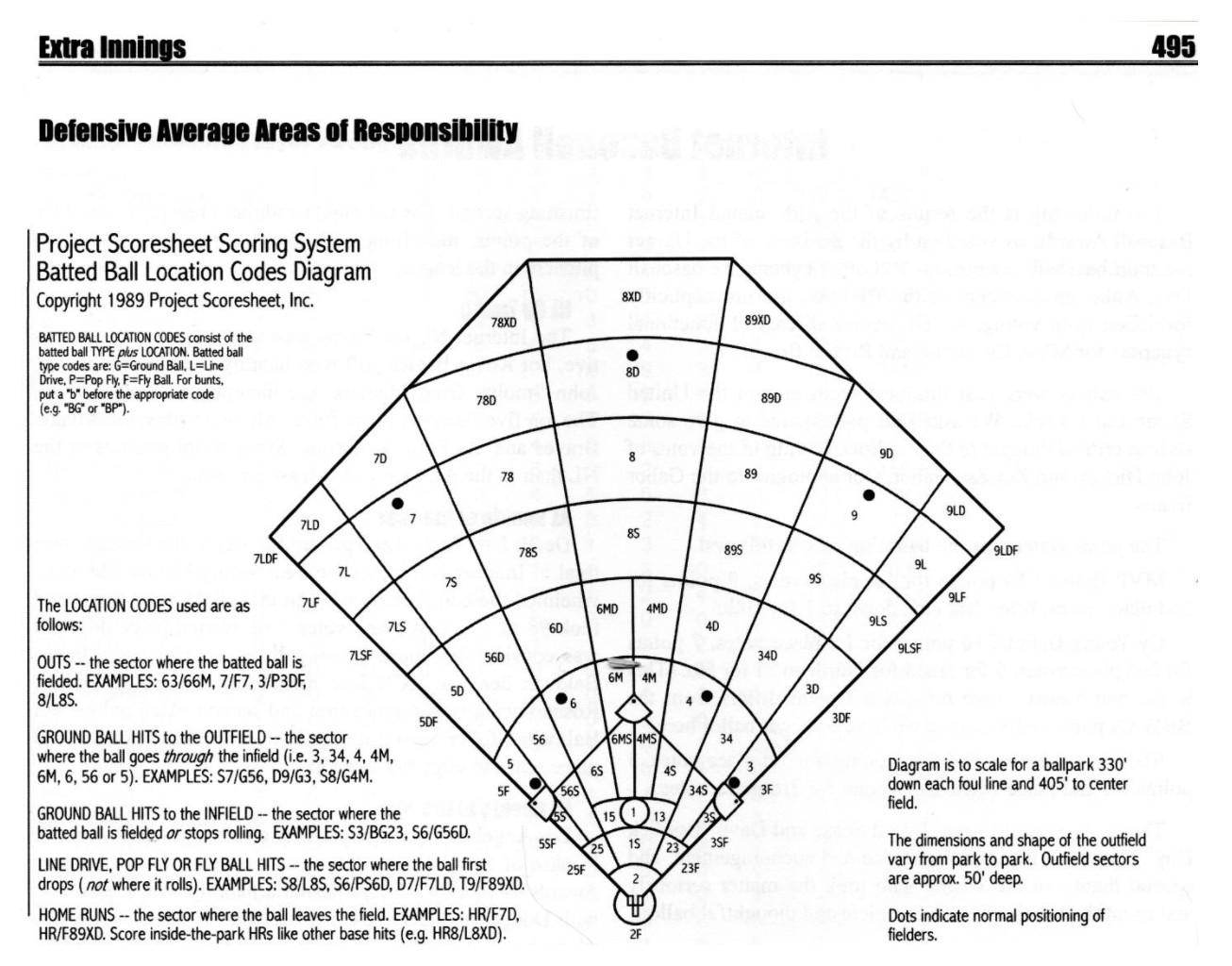

It was through SABR that Nichols eventually made the contribution to baseball stats that should have earned her an entry on my old Sporcle quiz. At the 1987 SABR convention in D.C., she met the late Pete DeCoursey, a fellow Project Scoresheet participant. Two years later, on a side trip to Cooperstown from the 1989 SABR convention in Albany, DeCoursey sounded her out about the idea of developing a defensive stat using Project Scoresheet information that would be far more accurate than the rudimentary and often misleading measurements available at the time, fielding percentage and Range Factor. The data they’d helped collect allowed for far greater precision: By 1988, Gillette says, Project Scoresheet had “probably 98 compliance” on recording the types and locations of batted balls, which gave them a near-complete record for that season (and partial records for the few preceding seasons) of whether each batted ball was a ground ball, line drive, fly ball, or popup, and where on the field it had fallen, as judged by citizen scorers armed with Project Scoresheet’s zone-based location diagram.

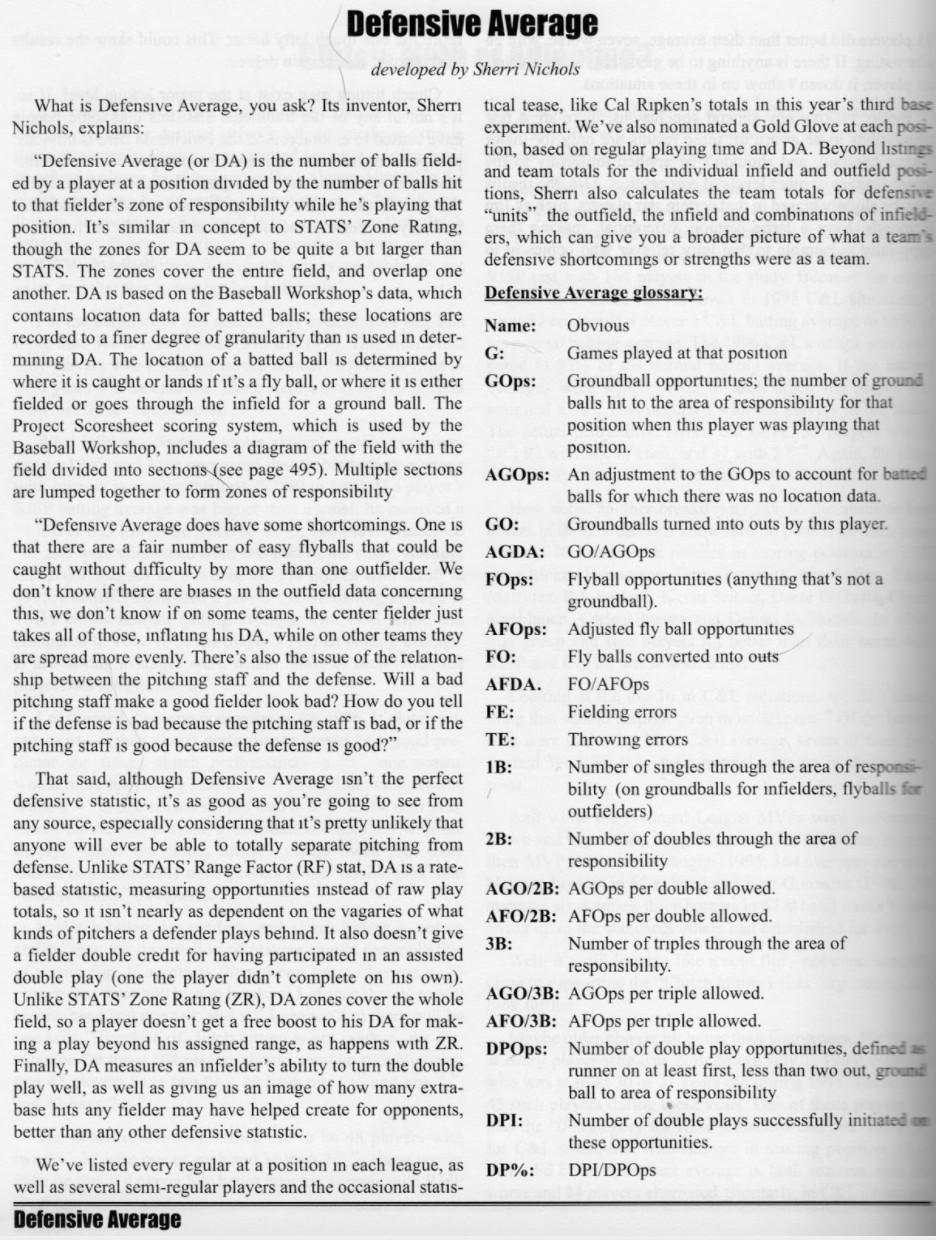

Nichols and DeCoursey called their system “Defensive Average.” As Nichols later explained in print, DA represented “the number of balls fielded by a player at a position divided by the number of balls hit to that fielder’s zone of responsibility while he’s playing that position.” That rate could be compared to other players’ averages at the same position or to a positional league average. DeCoursey wasn’t a coder, so he needed Nichols to implement the metric, which she did that year using the programming language C. “I did all the software development and number-crunching,” she says. Nichols had cocreated the first publicly available, zone-based defensive metric, a revolutionary precursor to stats such as Total Zone and Ultimate Zone Rating that are still widely used today. “It was the first I’m aware of because the data just hadn’t been there before,” Nichols says.

Sherri Nichols’s original DA/DR work is the framework for everything.Chris Dial, SABR director

Other systems of a similar nature were being developed independently during the same period, including an unnamed and unpublished metric designed by future UZR creator Mitchel Lichtman, and STATS Inc.’s Zone Rating, which (according to Dewan) debuted in the 1990 first edition of The STATS Baseball Scoreboard. Like the other stats, Defensive Average had its shortcomings: The system could unfairly penalize a fielder for playing next to a less rangy teammate, and the Project Scoresheet data was subject to human error. Those drawbacks notwithstanding, Defensive Average was a state-of-the-art attempt to illuminate baseball’s murkiest statistical subject. The methodology behind DA was both more transparent and more accurate than Zone Rating’s: It encompassed more of the field, allowed for overlapping coverage zones, and handled double plays more accurately. It was also the first public system adapted to express defensive performance in runs saved or allowed, dubbed Defensive Runs.

“I thought DA was a very interesting system that advanced our understanding of defense during that time,” Tippett says via email. Before spending 13 years with the Red Sox, Tippett developed the computer baseball sim Diamond Mind, which relied on Defensive Average ratings for a few years in the early ’90s. Subsequent stats also owe a debt to DA; “Defensive Average was definitely an influence on the development of UZR,” Lichtman says via email. SABR director Chris Dial emails an even more sweeping statement: “Sherri Nichols’s original DA/DR work is the framework for everything.”

Because DA was a drastic departure from traditional fielding stats, it produced some surprising results. “The differences between the reputations of players and what you actually saw in the data could be significant,” Nichols recalls. As she wrote on r.s.b. in 1990, “For a lot of people, good defense equals not making errors. There are certain players who have good hands but limited range who have the reputation of being good defensive players; these players tend not to do well in Defensive Average.” (In a later r.s.b. post, Nichols labeled that class of deceptive defender “Surehand Treestump.”) DA also saw through fielders who dove for everything and got to nothing; Nichols remembers A’s third baseman Carney Lansford as a prime offender. Nichols’s system dared to suggest that right fielder Jay Buhner’s rifle arm might not make up for his immobility; it also took on sacred cows such as Roberto Alomar and Kirby Puckett, who combined for 16 Gold Glove Awards but produced lackluster DA ratings.

Outside of SABR and r.s.b., DA wasn’t well known, but Nichols had opened the eyes of the cognoscenti. “The concept was a huge change in how I thought about defense,” Sheehan says via email. “Thinking of defense in terms of performance relative to opportunities to make plays was a big moment for me.” Jazayerli recalls, “We were so in the dark about measuring defense at all that her work was truly groundbreaking.” And Kahrl echoes, “The work she was doing on defense was game-changing because she was publishing simple, unchallengeable truths that in turn challenged what we thought we knew and what was … coming out of the garbled malarkey of sports journalism.” BP96 cited Defensive Average in four of its player comments; BP97 devoted a 20-page spread to DA, including complete player ratings for 1996.

1996 was the last season for which Nichols calculated DA; her daughter, Susan, had been born in 1995, and she says she drifted away from r.s.b. and baseball as she focused on parenting. But DA still survives under a new name and new management. In ’96, Dial says, he set out to “reproduce exactly what Sherri had done.” Using data from STATS and feedback from r.s.b., he rebuilt DA and later called the resurrected system Runs Effectively Defended, or RED.

In 2013, RED was selected as one of five defensive metrics that compose the SABR Defensive Index, which for the past five seasons has accounted for approximately 25 percent of the Gold Glove Award selection process, along with voting by managers and coaches. Despite RED’s ancient origins (by baseball-stat standards), testing performed by Baseball Info Solutions in 2013 showed that it performed better than the four other systems in the Index. As a result, it’s tied for the highest weighting in the SDI formula. At the dawn of sabermetrics’ internet age, Defensive Average was an obscure statistic that an informed few used to critique illogical Gold Glove selections from afar. Almost 30 years later, a metric directly modeled on DA is helping make those selections smarter.

Although Nichols faded from view online in the mid-’90s, she made one more major contribution to baseball. Through the Project Scoresheet newsletter, she’d met David Smith, a baseball researcher and microbiology professor at the University of Delaware. In 1989, as Project Scoresheet was winding down, Smith founded Retrosheet, an organization devoted to collecting box scores and play-by-play accounts for the whole of baseball history. In 1994, Retrosheet elected its first five-member board of directors, and because of her active roles in Project Scoresheet and SABR, her analytical output, and her relationships with Smith and other early Retrosheet members, Nichols was chosen as the organization’s first vice president and treasurer, a role in which she continued to serve through 2003.

“She was very significant in the early days of sabermetric analysis,” Smith says via email. “Her contributions were definitely cutting-edge.” Smith, who won SABR’s Henry Chadwick Award for baseball research in 2012, says Nichols’s significance extended to Retrosheet, too. “Sherri was key in our early policy decisions … and we are very fortunate to have had her as part of the organization in the crucial formative years.”

Luke Kraemer, who has served continuously on Retrosheet’s board since its start, remembers the most crucial moment arising at the first-ever Retrosheet meeting, which was held in Arlington at the 1994 SABR convention. Kraemer had recently used Retrosheet data to do paid research for a baseball game company, which caused an existential crisis for the fledgling organization: Would Retrosheet hoard data to make money or share it with the world? “Sherri came up with the idea of using the ‘library’ model,” Kraemer says via email. “Retrosheet would ONLY collect game accounts and make them freely available. It would not produce anything to generate income and no one would be paid. If funds were needed, we’d ask for donations but without the tote bags. Basically, everyone would be free to download any data to do with as they please as long as they give credit to Retrosheet as the source.”

In proposing that plan, Nichols says, she was guided by Richard Stallman’s free-software movement, as well as advice she’d once received from sports statistician Pete Palmer: Keep baseball a hobby. “[David and I] had watched Project Scoresheet fall apart over money, essentially, and had always kept in mind Pete Palmer’s advice,” Nichols says. “We also knew that the teams would be far more willing to cooperate if they knew we weren’t trying to make money. They don’t like it when people make money off of them, and they love it when people do things for them for free.”

The rest of the board approved her idea, and the first edition of the Retrosheet newsletter made a promise that the group has continued to keep: “All Retrosheet computer data will always be publicly available.” Kraemer says that while Smith’s founding of Retrosheet was its defining moment, “Sherri’s proposal was the second-most-important milestone in our organization’s history. It clarified how we went forward, which in turn, I believe, made it MUCH more realistic to locate and gather game accounts from baseball history. We’ll never know for sure, but I’m convinced that very few teams, reporters, announcers, [Hall of Fame], etc. would have ever allowed us to copy their scorebooks if we had any other model. And without all those copies, we’d be nowhere today.”

Instead, Retrosheet has acquired play-by-play accounts for 182,911 of the 194,908 MLB games played since 1901, giving the organization a 93.8 percent complete statistical accounting of the game’s modern era. That vast archive has made Retrosheet an invaluable resource for every public and private sabermetric researcher, including the ones who work for teams. If you’ve ever browsed the stats pages at Baseball-Reference, FanGraphs, or Baseball Prospectus, or read a sabermetric study that relied on historical data, you have Retrosheet—and Nichols—to thank.

In today’s statistically oriented era, a pioneering analyst like Nichols would soon find feelers from front offices in her inbox. In the late ’80s and early ’90s, though, the idea of a team responding to her research was still far-fetched. “MLB was not open to any of that at the time,” she says.

Trailblazing statistician Craig Wright, who became the first card-carrying sabermetrician to work for a major league team when the Texas Rangers hired him in 1981, says that no team at the time would have hired a woman in a role like his. “I have zero doubt that I [would not have gotten to do] what I did in 1981 if I had been a woman,” he says. Even a decade later, the industry wasn’t ready for a system such as Defensive Average, regardless of its source. “My impression in the late 1980s and early 1990s is that no team was paying attention to zone-based defensive systems and relied almost exclusively on visual scouting of defense,” Wright says. “I had to work tremendously hard to get my teams to consider my more evidence-based defensive evaluations, and the only method I could get a more open-minded response to was not a zone-based system. As far as material that would be taken in by a manager or coaching staff, that was not the right time to integrate sabermetrics, period. To add the foreignness of a woman who had never played baseball, that would have been unthinkable.”

Nichols’s lone brush with the big leagues backs up Wright’s words. During her days at Carnegie Mellon, she says, the school owned a piece of the Pirates. In 1989, Pirates brass asked a CMU VP to recommend someone who could help them with a statistical project. The request filtered down to Sherri, David, and a friend, who wound up in a meeting with a high-level executive at Three Rivers Stadium. All Nichols recalls of his request is that the executive wanted some statheads to rubber-stamp a case he was making to manager Jim Leyland. “They had already made up their mind what the answer was and just wanted something to beat the field coaches over the head with,” Nichols says.

The executive—who, according to Nichols, hoped (in vain) to persuade the trio to do the work for free—arranged a tour of the stadium, a meal in the press box, and seats in the grounds crew area underneath the section behind home plate, where the visiting quants could watch the game through a window. Nichols remembers the grounds crew grumbling about a woman being admitted to their man cave. “They were really uncomfortable with a woman being there, because then they felt like they couldn’t be themselves,” Nichols recalls. Later, she adds, “A pitcher who was on the DL at the time, he comes bouncing in there, cursing up a storm, ‘There’s a woman here!’” The memory makes her laugh. “I made them more uncomfortable, I think, than they made me,” she says. Nichols passed up the unpaid (and unstimulating) opportunity, and no other team ever contacted her.

Alan Schwarz, author of The Numbers Game, a 2005 history of baseball stats in which women rarely appear, notes that women were—and continue to be—a source of front-office talent that baseball teams tend to overlook. “What we’ve learned in the past 30 years, from Craig Wright to more than a few recent general managers, is that professional playing experience is no necessity to have a keen eye for finding and assessing talent,” he writes via email. “Well, a ton of non-playing smart people are women, and there’s no reason they can’t contribute as much as men. … Women are almost certainly the most untapped, high-reward group for front offices to tap.”

Teams are starting to come to the same conclusion. The first full-time female quant for an MLB team was likely Helen Zelman, who worked in the Arizona Diamondbacks’ Baseball Operations department from 2006-10. Sarah Gelles joined the Baltimore Orioles in 2011 and became the first female director of an analytics department in 2014. In Los Angeles, Megan Schroeder manages a Dodgers R&D department that also includes Emilee Fragapane. Several other teams have added full-time female analysts in the past two years, including Emily Blady (Chicago White Sox), Catherine Cage (Houston Astros), Kim Eskew (Rangers), Inga Milo (Milwaukee Brewers), Maggie O’Hara (Detroit Tigers), and Julia Prusaczyk (St. Louis Cardinals). That’s progress compared to decades ago, but it still makes women, as well as people of color, a small minority in a field that featured at least 156 full-time employees as of April 2016 and has added more than 70 full-time employees since then.

I know how hard it is to be in a field where there’s nobody like you. It’s a constant subtle message that maybe you don’t belong, that when you screw up maybe it’s more than just a mistake.Sherri Nichols

Gelles, who began working for Baltimore before the team had an established R&D department and was soon entrusted with starting one, says that stats have helped her set herself apart professionally in a positive way. “I think for me, analytics has been something of an equalizer in getting started in the sport,” she says via email. “Moneyball came out when I was a freshman in high school, and it not only introduced a set of jobs to me that I never knew existed, but it also made the industry feel accessible: If a man who hadn’t played baseball past high school could succeed in the industry, why couldn’t a woman with the same track record?”

Even so, she identifies with aspects of Nichols’s experience. “I’m not surprised [she] met resistance back then, and I have gotten more than my fair share of apologies for cursing in front of me, no matter how much I curse myself,” Gelles says. “The clubhouse environment makes the sports industry unlike other male-dominated fields, and Sherri’s experiences speak to that dynamic. It’s an issue that comes up with other women I speak to across sports, so it’s not unique to baseball. Unfortunately, I don’t know that there’s an easy solution. As more women are hired, it’s likely everyone’s comfort level with our presence will increase. But a good first step would be discussing the discomfort more openly.”

A second step, Gelles adds, would be promoting more women to highly visible positions, which would stimulate lower-level hiring. “I honestly don’t know that I would have had the guts to pursue this career if [MLB senior VP for baseball operations] Kim Ng and Helen Zelman hadn’t existed, and I imagine knowing about Sherri’s contributions would have been similarly encouraging,” she says. O’Hara, who also says that the lack of high-profile female front-office employees and previous R&D analysts was daunting to her, just teamed with writer Jen Mac Ramos of The Hardball Times to start a Facebook group that they hope can become a hub for aspiring non-cis-male analysts who are seeking connections, advice, and support.

Nichols, who says it would be gratifying if her story inspired others, has some support of her own to offer. Her advice, which she says took her time to learn and isn’t specific to baseball, is to “Find your voice. Use it. Trust your instincts. Believe in yourself. And when you find other people like you, embrace them, team up. Too often when I was a young woman in tech, I tried too much to be one of the guys, afraid of being dismissed if I hung out with other women. I didn’t understand my own power, and the power of women working together.”

Nichols says she never aspired to make baseball a full-time job. Maybe the thought would have held more appeal if the goal had been more attainable, but she has no regrets about declining an early offer to write for BP and leaving baseball behind before the ideas she espoused were widely embraced and the other diehards she hobnobbed with in the data dark ages went on to work for teams or gain more prominent public platforms. “That part of my life ended, and I moved on to other things,” she says, adding that her “life was pretty full and busy.” Today, she and David live in Redmond, Washington, where Sherri serves on the city’s planning commission and is currently training for her first powerlifting meet. As an NL-style fan in AL territory, she’s spared herself the hardship of Mariners fandom and now follows football and hockey more attentively than baseball, although she’s monitored the sabermetric movement closely enough to express concern about the number of baseball analysts being snapped up by teams and having their research sequestered. She’s also well aware of Statcast, which she says she finds fascinating, her voice betraying a touch of envy earned through years of trying to answer the same questions with less precise, and harder-earned, data.

Nichols’s 1980s innovations went beyond baseball. In 2016, she won an Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) Award for cocreating the Andrew File System during her years at Carnegie Mellon. The AFS, an ACM press release said, was the “first distributed file system designed for tens of thousands of machines,” and remains in use in large networks and cloud-based storage systems. Like Defensive Average, it’s often overlooked, but influential and foundational. “It’s kind of weird that this is coming up now,” Nichols told me when I first inquired about her baseball work. “All this stuff I did 25-30 years ago suddenly popping back up!”

The renewed public attention, perhaps, is sudden, but the work never went away. Nichols’s story is inspiring because it’s uncommon. The more it inspires, though, the more common it could become.