On April 18, Bruno Sammartino, one of the most iconic pro wrestlers of all time, died. He won the WWWF (now WWE) championship from “Nature Boy” Buddy Rogers on May 17, 1963, and held it until January 17, 1971, and again from December 10, 1973, to April 30, 1977. He’s remembered for his feuds with the likes of Superstar Billy Graham, Killer Kowalski, Gorilla Monsoon, and his erstwhile protégé, Larry Zbyszko, and for defining the pre-WWF era of pro wrestling. Upon word of his passing, Ringer wrestling writer David Shoemaker and Billions cocreator (and lifelong Sammartino fan) Brian Koppelman started emailing back and forth to eulogize Bruno and try to figure out what made him special. This is that correspondence.

Shoemaker: Brian. Bruno Sammartino died yesterday at the age of 82. I immediately thought of you—the first time we met, in a bar in Manhattan, you cornered me to talk about the WWWF that you grew up watching. Sammartino was the icon of the New York territory. There were other huge stars there in that era—Antonio Rocca, “Nature Boy” Buddy Rogers, Pedro Morales, the list goes on—but nobody captured the minds and rooting interests of the fans like Bruno did. It’s funny—as great as he was, I haven’t written that much about him over the years. Maybe it’s because WWE has done such a job of deifying him (despite their differences, more on which later, I’m sure). Maybe it’s because he’s sui generis—in the 1970s, Bruno was the living embodiment of pro wrestling, and his legend sustained for decades after, unlike most of his contemporaries.

But I’ll shut up—you were there. What was the first memory that came to mind when you heard that Bruno had passed?

Koppelman: Ugh. Springsteen said it best: “Everything dies baby, that’s a fact.” We all know this. But it doesn’t make it any easier when a hero falls. And somehow, it feels like writing about Bruno’s death is like writing about the death of the 9-year-old version of me. That’s how much he meant to me when I was that age. And here’s the specific memory: must’ve been summer, for two reasons (1) my parents let me stay up late and (2) SNL wasn’t on.

We had two televisions in my house back then—one downstairs and one in my parent’s bedroom. I spent a lot of time downstairs watching the Knicks alone or with my dad. But this night, my folks had company over. So they were downstairs, and I had to be upstairs. I remember going into their bedroom, turning on the TV and flipping channels. This was super late at night on a Saturday. And, as I said, Bill Murray wasn’t on. So I somehow landed on Channel 9, for the end of a harness-racing show. This in and of itself was so odd that I stayed with it, but then, right at midnight, the opening credits of WWWF Championship Wrestling hit. I had never heard of pro wrestling before this moment. But I was instantly, immediately, and forever hooked by the first words I heard, “The following wrestling exhibition requires discretionary viewer participation,” and the first images I saw: Eric the Red. Bobo Brazil. Bruiser Brody—there was some clip playing from a battle royale.

I knew I should go downstairs and ask permission to watch. Vince McMahon even sort of said that. But I couldn’t move. I was too captivated. I immediately felt about this the way some other kids did about the circus. But this was like the circus with all the boring parts cut out. There were flying acts—Mil Máscaras, Ricky Steamboat, etc. There were villains—Stan Stasiak, Baron von Raschke, Ernie Ladd, and Stan Hansen. And there was a hero—Bruno Sammartino, who instantly became my hero.

All these other figures had gimmicks. Ladd had the foreign object on his thumb. Stasiak had the Heart Punch. Hanson the Lariat. And it made them colorful and larger than life. But that’s because they didn’t have to be grounded. They didn’t have to sell the reality of this entire world of the things. Because that job was being done by one man, the man from Abruzzi, Italy, who had no costume, no gimmick, and nothing larger than life except for his gigantic, true heart and soul, which he put on the line night in and night out, for us.

Shoemaker: Maybe it was because I grew up seeing Bruno through Hulkamania-colored glasses, but I used to look at Bruno as someone out of pro-wrestling central casting. It took me years to really appreciate how great—and how charismatic—he was. What was it that drew you to Sammartino? As you grew up, what stuck out most about him in your memory?

Koppelman: I get that. To me, compared to Bruno, Hulk was a cartoon—a less dark, less weird, less specific version of Superstar Billy Graham. (But also, by then, I was a little older. Now, like you, I can look back and appreciate how/why Hulk became what he did.) Superstar was, in certain ways, Bruno’s great rival in the ’70s—and the man who finally took his belt. And a look at him sort of reveals the answer to your question about Bruno: Superstar was all about the exterior, the flash, the ego. Bruno was all about earnest belief that justice will win out, that hard work would be rewarded, that if you were willing to disregard all the nonsense (and that’s a Bruno word, “nonsense”—he’d never say “bullshit” or even “crap”) and outwork the other guy, you would win.

As you know, they used to divide wrestlers into not only good guys and bad guys, but also into these subcategories of scientific wrestlers and brawlers. Pedro Morales was the paradigm of the scientific wrestler, I guess. Bruno was known as a scientific wrestler who could also brawl, right?

I understand how Bruno could look—from a distance—not only like a central-casting wrestler, but also boring. The thing is, his charisma, his charm, the essential kindness coming off the man, made him the opposite of boring. And then, in the ring, his strength and intensity were surprisingly effective.

Somehow, without bragging, without showboating, without artifice, this man communicated his entire life story—not a fake wrestling-made story, but his actual story—with every move he made and every word he spoke. You just knew, watching, that this wasn’t someone playing a good guy. This was a real good guy. And in 1976, with the country where it was, with the discontent so great that even a 9- or 10-year-old could feel it, that really meant something important.

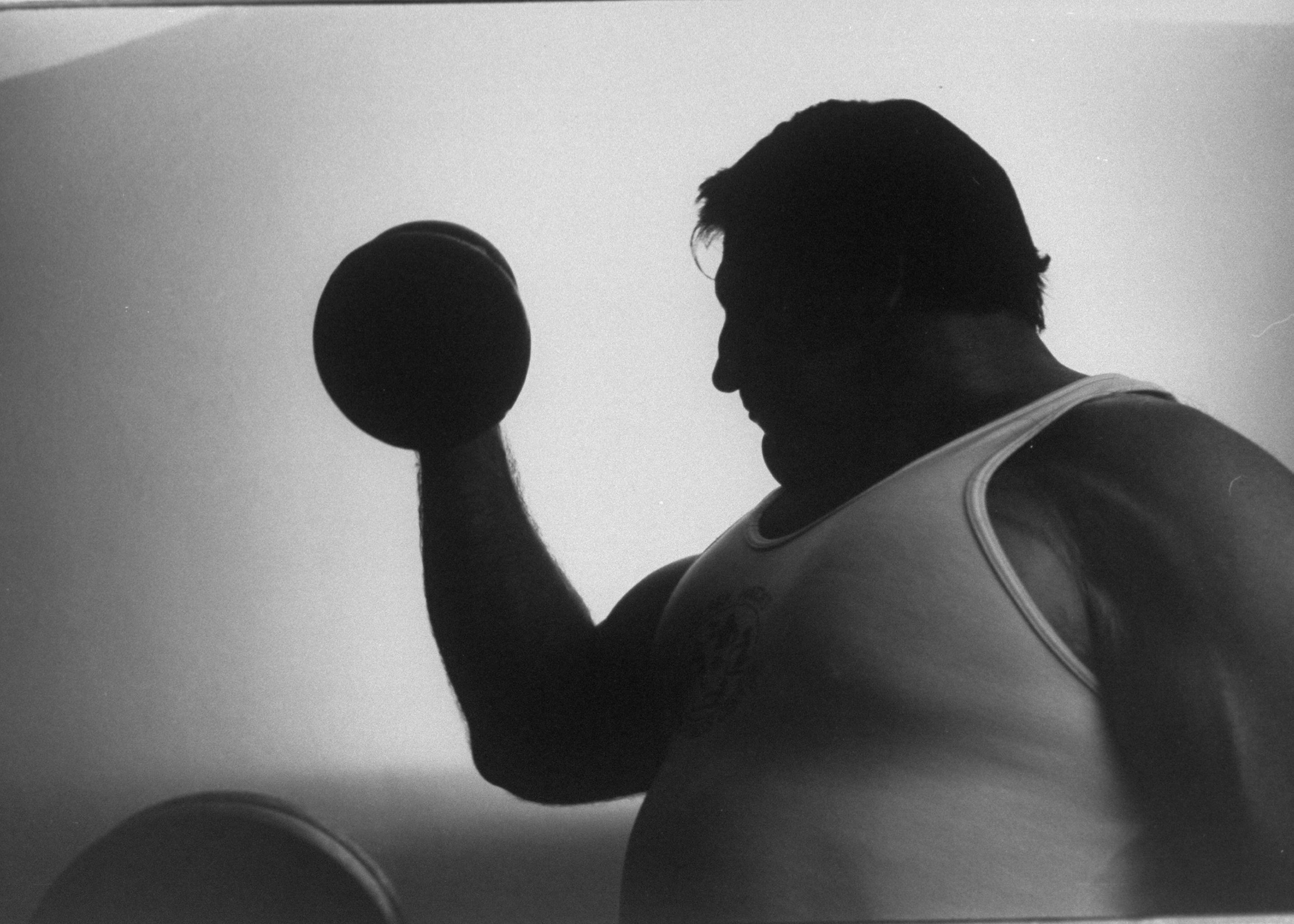

Shoemaker: You mention his life story. Bruno’s got a hell—sorry, heck—of one. He grew up in Italy, where four of his seven siblings didn’t survive past childhood. The remaining family hid from the Nazis in the mountains for 14 months, and he eventually immigrated to America in 1950. He was a scrawny guy who found his calling in the weight room, almost made an Olympic team, and set a bench-press world record. When he signed with Capitol Wrestling nine years after he came to the country, he was already living out the American dream. Vince Sr. must have seen it, too. Bruno won his first match in 19 seconds. He beat “Nature Boy” Buddy Rogers for the belt four years later—famously in 48 seconds. Bruno always tells the story as if it were a shoot—”We can do this the easy way, or the hard way”—but regardless, it’s part of his creation myth. Rogers had a lot of Graham in him, and he was an iconic figure in his own right, and Bruno ended his epic reign in the blink of an eye. Why do you think Bruno was the guy that Vince Sr. chose?

Koppelman: Well, the great thing about the shoot story is this: Bruno never broke kayfabe. Even when wrestling became sports entertainment, he never admitted it. But he did tell the full Vince Sr.–Buddy Rogers story on Colt Cabana’s podcast. And it’s a must-listen.

Bruno forced Vince Sr.’s hand. Buddy Rogers had Bruno exiled from the territory because when Bruno wrestled on the same card as Buddy, the audience began cheering louder for Bruno than they booed for Buddy. They saw in Bruno what I saw. And Buddy didn’t like it. So Bruno left. And at first, the other territories honored Vince Sr.’s request and they black-balled him. So Bruno went up to Montreal and quickly became the biggest star in that territory. He became so important up there that Vince Sr. realized he had to have Bruno back.

Did Bruno really beat Buddy in a shoot? I think I need to believe it. And even if it wasn’t a shoot in the ring, it was a life shoot. Buddy wanted to stay champ. And Bruno, by working hard, by traveling far, by being the great draw he was, created the momentum and leverage to oust him.

Does the kayfabe thing mean anything to you? To me, the code he held to is inspiring. He didn’t want the old guys and kids who believed in him, who believed that he fought for them, to lose out on that ideal. And so he refused to go along. I love this. Do you?

Shoemaker: I love it. There’s a lot to unpack—some wrestlers, especially the truly great ones, live the life so fully that they don’t even see the line between real and unreal. Kayfabe isn’t a code of conduct, it’s their real, all-consuming life. And there are a lot of these stories where reality is written back into these fake fights in post—look at Hogan saying he was unsure about the finish at WrestleMania III in the Andre the Giant documentary.

It’s a way to reclaim kayfabe in the postmodern era. But you’re right that Bruno was a little different. Keeping up the facade was integral to the character he portrayed. Or rather, the character he lived. He was the little guy with the near-tragic backstory who conquered the world with grit and self-confidence and determination. The part about Montreal—that’s 100 percent real, and that’s the most compelling part. It almost doesn’t matter what really happened between him and Rogers, because in real life he went and earned the title in a way that very few other pro wrestlers can claim to have done.

You mentioned Bruno’s code of conduct—the no cursing was symbolic of the ideals he lived out every day. And that ended up being one of the concrete reasons a rift developed between him and WWE in the ’90s, because the show became so crass. There was the failure of his son, David, as a pro wrestler in the WWF—that affected him deeply. But it’s safe to assume that the wrestling world turning its back on kayfabe was a huge contributing factor to his disillusionment as well. Eventually he was brought back into the fold by Triple H and was inducted into the WWE Hall of Fame in 2013. Do you think his absence from WWE in the modern era, before he mended fences, hurt his legacy? Does it even matter?

Koppelman: I think, in the end, his fallout with WWE will burnish his legacy. Because he lived it so darn hard that he risked being Photoshopped out of official wrestling history. Since Triple H did bring him back, did broker the deal, then, just like Montreal proved, Bruno’s will always triumphed, his heart always won.

And as far as the actual Hall of Fame induction: I was there. I hadn’t been to a wrestling show in over a decade. Hadn’t been watching. But when I heard Bruno was getting inducted, I knew I had to be in the building. And that I didn’t want to go as an insider, as a filmmaker with VIP status. I went online, bought a pair in the rafters and forced my son to go with me. He was studying for the SATs and tried to get out of it. But I told him that certain things mattered more than tests. And one of those things was being with his dad on these sacred occasions. So we went. Me in my Bruno T-shirt. Him with his STUDY GUIDES in his lap. And I’ll tell you, man, when Bruno walked out there, into the arena he sold out countless times, the applause was thunderous and extended and from the deepest imaginable place. He was thin, mustached, barely recognizable. Except by his posture, attitude, and voice. All of which served to bring a kind of grace, dignity, and renewed hope back into that building. I’m not gonna tell you I cried. OK. I’m just not gonna tell you that. Were you ever in a room with him?

Shoemaker: I never got to meet him, and now you’re making me feel heartbroken over that. I don’t always love meeting the old-timers and legends, because they’re often either jaded or (as we discussed) lost in a kayfabe miasma. And there’s a weird juxtaposition—you want your idols to stay the same forever, but seeing them hanging onto their personas in their waning years is a bit depressing. But I’ve watched a lot of Bruno tape, both in his heyday and from recent years, and you’re right—he aged more gracefully, and humanly, than most of his contemporaries. What made his Hall of Fame speech so compelling was that it was so utterly human. He told his early life story and ended talking about how he was still training at 77 years old. That he got to do it at Madison Square Garden, where his big heart, as you put it, and his humanity were so often on display.

MSG was the seat of Northeastern wrestling and, in a lot of ways, the birthplace of the modern WWE. And Bruno owned MSG. According to WWE, he headlined there 211 times and sold it out 188 times. That’s just amazing, especially in a world where every story has already been told countless times before. What was it that made Bruno different, do you think? He was part of a lineage of ethnic wrestlers that appealed to the immigrant and blue-collar classes, but his appeal obviously transcended Italian Americans. What made the crowds line up, 20,000 strong, month after month?

Koppelman: It’s a little like asking why folks go see Tom Cruise movies. They go because something about the way in which he carries out the duties of his job demands their eyes and ticket money. Men and women are revealed by the camera. Their truest, deepest selves come through. If we connect strongly enough to that essential quality in them, we find ourselves wanting what they want, taking on their defeats as our own and their victories as our own hard-won victories. The squared circle works the same way. The crowd felt that Bruno Sammartino was in there, fighting for good, fighting for them. You know: He never presented himself as the smartest guy, the quickest with the insults, the coolest. But he was the toughest. He’d keep coming. And he showed those fast-talking smart guys who cut corner what really mattered. And in a time of upheaval and strife, that resonated.

Shoemaker: Two things. One, on the Tom Cruise front: Many leading men have come and gone during the Cruise era, and every time we think he’s done, he keeps coming back. Bruno was a little like that. Bruno lost the world title to “The Russian Bear” Ivan Koloff in 1971 in one of the biggest shockers in MSG history. The idea was to transition the title over to Pedro Morales, but Morales didn’t click the way Bruno had, and McMahon put the title back on Bruno the next year. My favorite part of the story was that Vince Sr. practically begged Bruno to take the title back, and Bruno was initially unmoved. It took McMahon promising him a cut of all the gates for him to agree. That’s a Hollywood power play if I ever heard one.

Second thing: You mention his toughness. In the spring of 1976, Bruno broke his neck in a match against Stan Hansen; he spent weeks in the hospital, but he rushed back to the ring and two months later—two months—fought Hansen at Shea Stadium. That neck injury was the bellwether for the end of his championship run, as he asked to be relieved of the title a year after due to accumulated injuries.

Which was more shocking to you: the first title loss or the broken neck? Can you even compare them?

Koppelman: I was too young when Koloff beat him. I just read about it. And the thing I always loved was that Stasiak got to have the belt for that incredibly short window just to dump it to Bruno. And I love that Bruno beat Vince Sr. at his own game, getting the gate share.

The broken neck though—that was as central to my thoughts at that time as whether or not Vinnie Barbarino would come back to Welcome Back, Kotter. I was obsessed with how Hansen broke it, why the refs allowed the lariat to be loaded like that, and when Bruno was gonna come back and beat his ass.

In truth, by then, I knew wrestling was a work, but I also knew that Bruno had really broken his neck, so it was one of the first times I had to deal with the idea that in the real world, true clarity was hard to come by. That said, when he did come back, and won the fight, I nearly lost my mind.

The thing about the world back then is this: It was small. There was no real cable TV. There were only a few channels. And a few very famous, transcendent athletic stars. Bruno was one of them. But he was also in the freak show, the sideshow, and so, for those of us who belonged there too, who needed to see something strange and canted, but also wanted something human enough that we could really connect, he was everything. When he had that neck collar on, and could barely move, but promised that someday, soon, he’d get his revenge, we not only believed him, but we also counted on it.

And that’s where I’ll leave it, I guess. You go through life and you learn there isn’t much to count on. Your family. Your closest friends. The person you choose to marry, maybe. And, once in a while, there’s a hero in the world you decide to trust, to lean on, to ride with. For me, from ages 9 to 16, that was Bruno Sammartino. And he never once let me down.

RIP, Champ.