“So let’s say you take a wooden ship,” says Tully (Mackenzie Davis), preparing a question that is as philosophical as it is rhetorical by way of making conversation with her boss, Marlo (Charlize Theron). They’re sharing a night off from their work as, respectively, a night nanny and a new mother. “And you replace one plank a year. Is it still the same ship?” No, Marlo replies, as though she has already considered this question and is ready with her answer. “It’s a new ship. It just is.” “But what about people?” Tully counters. The two of them have spent the first two acts of screenwriter Diablo Cody’s most recent collaboration with director Jason Reitman, Tully, debating the nature of cellular change in mothers and children, and it is in this third act that the two of them begin to speak as much in truths as they do in riddles. “I guess I’m just not me without the original parts,” Marlo responds.

Whether Tully is explicitly referencing The Argonauts, Maggie Nelson’s 2015 memoir about marriage and family, is unclear, though it’s not impossible. (This conversation takes place at a bar in Brooklyn, where, at any given time, there are many conversations about Nelson happening.) The Argonauts was a blend of critical theory and love story, explaining how, in the course of marrying artist Harry Dodge, Nelson found herself trying to make her person a cohesive whole out of so many frequently changing parts: a mother and a stepparent, a queer woman, a reader, a writer, and an artist, a teacher and student. Early in the book she cites Roland Barthes’s description of the Argo, a ship from Greek mythology blessed by Athena and the first vessel to sail in the sea, and how it relates to the person who says I love you— “Just as the Argo’s parts may be replaced over time but the boat is still called the Argo, whenever the lover utters the phrase ‘I love you’ its meaning must be renewed by each use.”

When Tully begins, Marlo is in the last days of her third pregnancy. She’s 40 years old, with two kids she loves and a husband she likes, and this pregnancy is not unwanted but very much unplanned. Marlo is aware of how phrases can renew in their repetition—more than that, we are meeting her at a moment when she is very aware of how they can also be used to avoid real feelings. “Such a blessing,” she says whenever someone comments on the upcoming baby, her tone flat and her eyes traveling away from their faces.

Marlo, we learn through some rapid-fire exposition in the first few scenes, comes from a poor family. She’s a human resources manager for a protein bar company, and her husband, Drew (Ron Livingston), has the kind of dad job where no one knows what he does all day (he “audits organizational paths and systems in a corporate structure”—what? Anyway, he travels a lot). Two incomes for two kids is safe, but two incomes and three kids is precarious enough for concern. Craig, Marlo’s brother (Mark Duplass), meanwhile, has become some kind of millionaire, and he wants to pay for a night nanny because he doesn’t want “what happened last time” to happen to her again, implying postpartum depression. Marlo resists, out of pride and class anxiety, saying it’s like the plot of a bad movie where she’ll end up walking with a cane; later she tells Drew she feels weird about outsourcing the work of her life. But after the daily struggles of parenting three children, and too many sleepless nights of rote repetitive caretaking, Marlo snaps in the principal’s office of her kids’ school, screaming that she can’t take all these people who won’t just say what they mean. In the front seat of the car, crying almost as hard as her baby in the back, she takes out the night nanny’s number to finally accept the help she needs.

Much like the scripts for Cody’s films, the press notes cannot resist a few puns, calling the genesis of the idea “The Seed” and explaining that Tully was “conceived,” after Cody gave birth to her third child and hired her own night nanny. Mary Poppins is cited as Cody’s inspiration for the Tully character, and it is worth remembering that Mary Poppins came to take care of the Banks children because their dad was too busy making money and their mom was too busy being a suffragette. Tully does show up like Mary Poppins, absent an enchanted umbrella—we don’t see an interview, or any sort of vetting process, or even watch Marlo make the phone call after she finds the number buried in her purse. We just see Tully appear at the front door and take stock of the scene she’s been called into.

The next morning Tully is gone and the house is clean. Marlo wakes refreshed and at peace. Over the next few weeks, they spend their nights talking, making Tully’s night shifts feel more like a slumber party. Tully goes above and beyond her job, acting as some kind of wish-fulfillment therapist—when Marlo confesses she wants to be the kind of mom who surprises her sons’ class with nut-free cupcakes, Tully makes them after Marlo falls asleep, and her son Jonah’s pride as he carries them into his classroom is so pure it hurts.

But it is Tully who is something of a mystery: Where does she live? Why does she do this work? Most mysterious of all is Tully’s relentless curiosity about Marlo, the way she asks her about her life, her memories, her feelings, pushing her to say what she means without hiding under jokes or sarcasm. They have, it turns out, a lot in common: They both prefer liquid black eyeliner when they wear makeup, their drink is bourbon, and they love to watch Ladies and Gentlemen, the Fabulous Stains. Their dynamic is mysterious, too, and, fair warning, does not go where one might expect. But that cautious, excitable curiosity between new friends persists throughout almost the entire film, the two of them circling around what they want to say without knowing whether they can trust themselves to say it, or the other to hear it. Tully’s prodding is gentle, without hostility. Even when she pushes back she does so sensitively, giving Marlo permission to tell the truth, which is: She didn’t really have bigger dreams than the life she’s currently living. When Marlo has a few too many bourbons at her old neighborhood bar, she comes close to revealing a secret, but Tully stops her by quitting without an explanation. Like Mary Poppins’s abrupt departure after a few weeks of magic, it’s just time for her to go.

As Tully opens in theaters, there are multiple new books about motherhood that can be read like thematic companions: Motherhood, by Sheila Heti, a novel about an unnamed narrator in her late 30s who questions herself and everyone around her about whether or not she should have a baby; And Now We Have Everything: On Motherhood Before I Was Ready, Meaghan O’Connell’s nonfiction book about her unplanned pregnancy and her first year of being a mother; and Jacqueline Rose’s Mothers: An Essay on Love and Cruelty, an expanded collection of essays about motherhood as a political, cultural, and artistic question that began with Rose’s writing for the London Review of Books. All of them approach the subject as irrevocably contradictory, proceeding from the assumption that motherhood is the most private of questions that also demands the most public of answers—do you or will you questions that are considered to be both a woman’s deepest personal reckoning in the midnight hours of her soul as well as totally appropriate cocktail party conversation.

Heti’s book, like many of her novels, takes the mind as the primary setting, and thoughts are the major source of action: narrative arcs begin and end with the progress of her characters’ thinking, and the process by which they arrive at their conclusions. In Motherhood, this style suits the subject well—we’re brought so close to the narrator’s ongoing internal monologue that soon her thoughts start to feel like the reader’s. The more she thinks, the closer she gets to an answer to the real question posed to people with uteruses, not what if or why but where. Where are your children? As though they are—even when they are not just unborn but entirely unthought of—missing. “Whether I want kids is a secret I keep from myself,” she tells us. “It is the greatest secret I keep from myself”—and it is the wanting she fixates on rather than the action, separating the decision from the doing.

It is the ordinariness of the experience that the narrator fears the most, explaining that she worries having a child would be “a simple human act that I would never be up to fulfilling. So I fear it will be the first moments in the delivery room, after having my baby laid on my chest, when it will hit me in a similar way as to how those moments dawned: there’s nothing magical here either, just plain old life as I know it and fear it to be.” On the other hand, she wonders whether she’s suppressed her desire for children so much that her desire is unrecognizable. All of this endless thinking and deciding and wondering and second-guessing, she says, “suddenly seemed like a huge conspiracy to keep women in their thirties—when you finally have some brains and some skills and experience—from doing anything useful with them at all.”

O’Connell’s book is also concerned with women’s work—what it is versus what it should be. She had a plan for her life: a spring wedding, a trip around the world, grad school, writing. She makes a friend promise to slap her if she has a baby before she writes a book. Instead, she gets pregnant almost immediately after the engagement, and the book follows their halting decision to start their family sooner than expected. O’Connell really, really wants to have a baby—this baby—and her book also makes a map of all the places her thoughts go, struggling to find an honest answer to the question of whether being a writer and a mother is possible for her. During the chapter on her labor—a days-long process in which she experiences multiple agonies, including what the doctor calls a pain-relief “blind spot” that the epidural couldn’t cover—she writes of an epiphany she experienced. “I felt like a madwoman, existentially alone, climbing the walls. Then came a strange, unwelcome solidarity with all women. The certainty that we were damned.”

If such solidarity exists, it might be as desolate as O’Connell feels in that dark moment, and it is certainly not now nor has ever been one that can be described as cohesive. In Rose’s Mothers, she, like Heti and O’Connell, also follows the question of motherhood through the mind and through the delivery room, but with a focus on the greater cultural issues that being a mother provokes and demands. “A simple argument guides this book,” Rose says to begin. “That motherhood is, in Western discourse, the place in our culture where we lodge, or rather bury, the reality of our conflicts, of what it means to be fully human.” Rose writes that solidarity among mothers, “across class and ethnic boundaries, is not something Western cultures seem in any hurry to promote.” She talks about the way maternity is at the center of immigration, health care, identity, and community, as well as works of art that take mothers of all kinds as their subjects to very different conclusions—there’s an entire chapter on the way Elena Ferrante writes about mothers and daughters, while Medea is the classic example of the ultimate taboo, the mother who kills her children. To contrast, Rose revisits Toni Morrison’s Beloved, written as a fictionalized retelling of the true story of Margaret Garner and decidedly not as Morrison’s retelling of the Medea myth, but a story of maternal sacrifice that is necessary in an evil world. Morrison said she wrote the novel to reveal a side of America that white Americans would like to repress—“that in an inhuman world, a mother can only be a mother in so far as history permits,” Rose concludes.

As Parul Sehgal wrote in a wonderful review of Rose’s book, we now have “radiantly specific dispatches from almost every corner of motherhood” at our disposal, from the three books listed above to stories about infertility, fatherhood, and genre books such as the French thriller The Perfect Nanny, a true-crime-inspired novel about a nanny who kills her charges, soon to be adapted as a film. There’s a book for every anxiety. And yet Sehgal points out that when the books are taken together, readers and viewers will witness a different phenomenon than motherhood: how it “dissolves the border of the self but shores up, often violently, the walls between classes of women.” Each writer has their own experience and their own ideas, yet somehow all of these new parts become a recognizable whole. In many ways, Sehgal writes, if readers and thinkers are already familiar with the unanswerable questions and unspeakable answers of motherhood, then “the real work, the daring work, might be for these mothers to look at each other.”

When anyone but Tully looks at Marlo, they seem to see an object of pity. “I love my sister,” Craig says at one point, “but these last few years it’s like somebody’s snuffed out a match.” This is a pretty cruel thing to say about an exhausted and overworked woman, particularly by a man who lives in a gorgeous glass bungalow complete with a basement tiki bar, a Mercedes-Benz G-Class SUV, and three children attended to by a nanny with a master’s degree in early childhood education and some very evocative opinions on how chicken nuggets are made. But in Theron’s performance we can see that it’s true: She wants to be the mom she thinks they deserve, and she simply does not have the time or energy. Marlo’s youngest son, Jonah, is “atypical,” the word used by specialists when a set of behaviors resists a single diagnosis, and she is struggling to find him a school that fits and a routine that works without neglecting her older daughter, Sarah. Her depression is shown as being a reasonable response to a trying situation, an ongoing part of who she is as a person, and a secret she is keeping from everyone who claims to love her.

Tully has been described as completing an unintentional trilogy within Cody and Reitman’s partnership. Juno starts with an unplanned pregnancy, too, and while the dialogue is often the most remembered aspect of that film, it’s mostly a story about three very different kinds of moms: Ellen Page as Juno, the biological mom entering an open adoption with Jennifer Garner’s Vanessa, as well as Allison Janney as Bren, Juno’s protective and funny stepmother. Young Adult functions as a kind of parallel story to the role Theron plays in Tully—as Mavis, the manipulative popular girl who grew up to be a manipulative ghost writer for a Sweet Valley High–type young adult novel franchise, her greatest accomplishment is getting away from her small town to the closest approximation of a big city. The climactic reveal of her secret is that she almost stayed and married her high school boyfriend, almost had a baby, almost chose the life she claims to have run away from, and that she left it behind only after having a miscarriage.

The element I like most in Cody’s writing is the way she turns over relationships between women so that we can see how they are necessary, and terrifying; the capacity to hurt and be hurt is under the skin of every girl on screen. Marlo says as much to Tully when she tells her, bluntly, that “girls don’t heal.” Jennifer’s Body is probably the best example of this, though it’s about power dynamics between teenage girls who occupy different statuses in a high school hierarchy. But it’s very much there in the tenuous intimacy between Juno and Vanessa, and certainly there in Young Adult, in which the only women Mavis can identify are enemies or enablers. Early on in Tully, Marlo bumps into a woman at a coffee shop whom she knows, it transpires, from living in Bushwick many years ago, and whose presence unnerves them both without us really understanding why. Later she reveals that the woman she saw in the coffee shop was Violet, and they were once in love; it’s strongly implied Marlo left her to marry her husband instead.

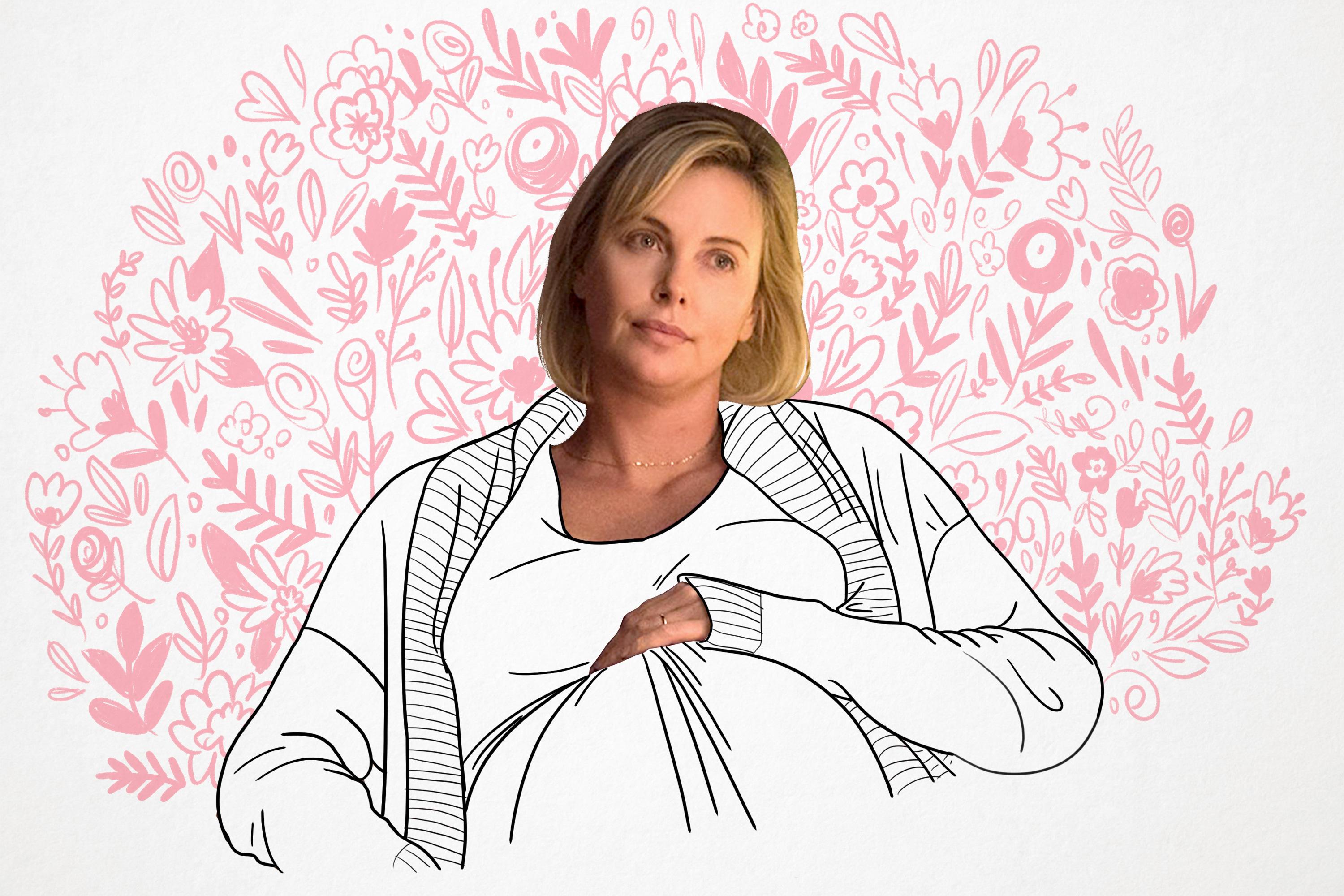

Theron plays both of her roles in Cody’s recent movies equally well, showing how both women are collapsing under the appearances they feel forced to present to the world. Over the course of her career, Theron has often played roles that appear to downplay her inherent beauty, though this isn’t quite accurate. While other actresses are, sometimes quite literally, falling all over themselves to offset the beauty their movie stardom mandates, Theron is one of the few who still works with an understanding of what her face is capable of—she knows what beauty means and what it does, both in its construction and in its absence. Being beautiful is work, these roles remind us, and we conflate ugliness with what is often simply a lack of money, time, resources, or access to any combination of those three elements. Theron will always have Theron’s bone structure, but in the absence of sleep or moisturizer we have Marlo, a tired new mom with a face and body at the mercy of everyone else’s scrutiny.

Like in most of Cody’s movies, the other women currently in Marlo’s life are gently hostile—there’s the kind woman at the coffee shop who wants to make sure Marlo knows her decaf latte could have trace amounts of caffeine, or her sister-in-law, who commands Siri to “play hip-hop” before they sit down to a meal seemingly prepared by a private chef. Cody, too, has always been excellent at writing men who are inept, nice enough but either useless or harmful in their absence or uninterest, like Jason Bateman’s failed musician in Juno or Patrick Wilson’s benignly boring high school jock turned suburban dad in Young Adult. It’s telling that Craig is concerned about Marlo’s mental health but does not offer to give her, for example, access to therapy; he also doesn’t acknowledge that his sister might be best helped by cash she can spend as she sees fit, even when she says as much. Drew is probably a good dad in a lot of ways, but he clearly sees his role in the house as someone who comes home for dinner and helps the kids with their homework. In brief, this is a bleak and lonely life for Marlo: Other women are a danger, men are no help, wealth is embarrassing, and poverty is unthinkable.

In 1974 the film critic Molly Haskell published From Reverence to Rape: The Treatment of Women in the Movies, aiming to show how film had “portrayed—and betrayed—women.” Movies, Haskell argues in the book’s introduction, are one of our clearest and most accessible “looking glasses in the past, being both cultural artifacts and mirrors,” and she finds common themes in the ways women are written: either idealized as idols of sensuality or untouchable maternal martyrs. Sometimes, Haskell writes, we can find transcendent characters that recognize a reality “where children are not their mothers’ pride and joys but their jailers, carriers of a disease called middle-class family life.” Haskell goes hardest when she looks at films that insincerely canonize mothers for sacrificing their lives or happiness to their children, arguing that this mentality is “a disease passing for a national virtue. … Martyrdom must be proportionate to guilt, and the greater the aversion to having a child, the greater the sacrifices called for.”

It is perhaps a sign of progress that Tully does not require an entirely proportionate punishment for Marlo’s ambivalence about motherhood, or her insecurities about parenting. Admitting these feelings does not lead to literal death or destruction, though I will share one spoiler when I say the movie does come close, and makes her early prediction come true: By the end of it, she is walking with a cane—injured a little, yes, but doing her best to heal.

In the absence of a tragically virtuous death, however, Tully leaves us instead with a strange and simple reduction of the ideas presented throughout the film. There are recognitions of pressing material concerns of inequality and suffering in seemingly sweet domestic spaces, but ultimately, they circumvent these impossible questions of love and duty with a twist ending that plays like a casual betrayal. Marlo is lonely, the film proves over and over again, because she needs someone to talk to and someone to listen to her; she needs a friend, or someone to trust, or a real partner in her life, or even just time alone with a book that provides her with some sense of hey, same. She needs, like so many mothers before and beside her, not more alone time, exactly, but to be together with someone else in her thoughts. Rather than considering what it would mean for Marlo to say what she needs and what it would look like for her to get it—or, for that matter, instead of considering the question of what kind of relationship can develop between two women tasked with child care for two different but equally urgent reasons—Cody and Reitman choose a fairy tale fantasy that sacrifices the most essential part of the story. The film leaves Marlo changed but in the same place, and if anything it should begin at the moment it ends: Where will Marlo go, as a person and parent, now that she’s accepted that her new parts are just as much a part of her as the old parts? Will she say what she means and demand a more equal relationship with her husband, or have a more honest conversation with her brother, or maybe find Violet? That’s the most crucial question, I think: When will she find another woman she can love and trust?

The best parts of Tully are the scenes of two women making time for honest conversations—of how much mothers and all kinds of parents and caretakers need to talk to one another, and how much good can come out of asking for or offering help. I only wish there was more of that. When explaining “Wages for Housework,” the Italian socialist feminist campaign started in 1972, Silvia Federici said: “As we so often repeated, what we need is more time, more money, not more work. And we need daycare centers, not just to be liberated for more work, but to be able to take a walk, talk to our friends, or go to a women’s meeting.” I remembered this most recently a few weeks ago when I was visiting a friend and her newborn baby. We lay in her bed with the baby between us and talked for a long time, until she said she needed to buy some basic food items. I offered to go to the grocery store for her; no, she said. She wanted to run her errands by herself. She wanted to take a walk alone with her thoughts, and then she wanted to come home and keep talking.