On May 31, about 600 people packed into New York’s Bowery Ballroom for the Gaslight Anthem’s first local show in more than three years. The four-piece New Jersey punk outfit had stepped away in 2015, a necessary hiatus that some thought might be permanent. Yet when the 10th anniversary of the group’s seminal 2008 album, The ’59 Sound, rolled around, there was no choice but to literally put the band back together for a series of shows in which they played the record in its entirety. As the anticipation built inside Bowery that night, resale tickets were going for more than $300 outside. What followed was a familiar scene for the Gaslight Anthem: a packed house crowing every single word.

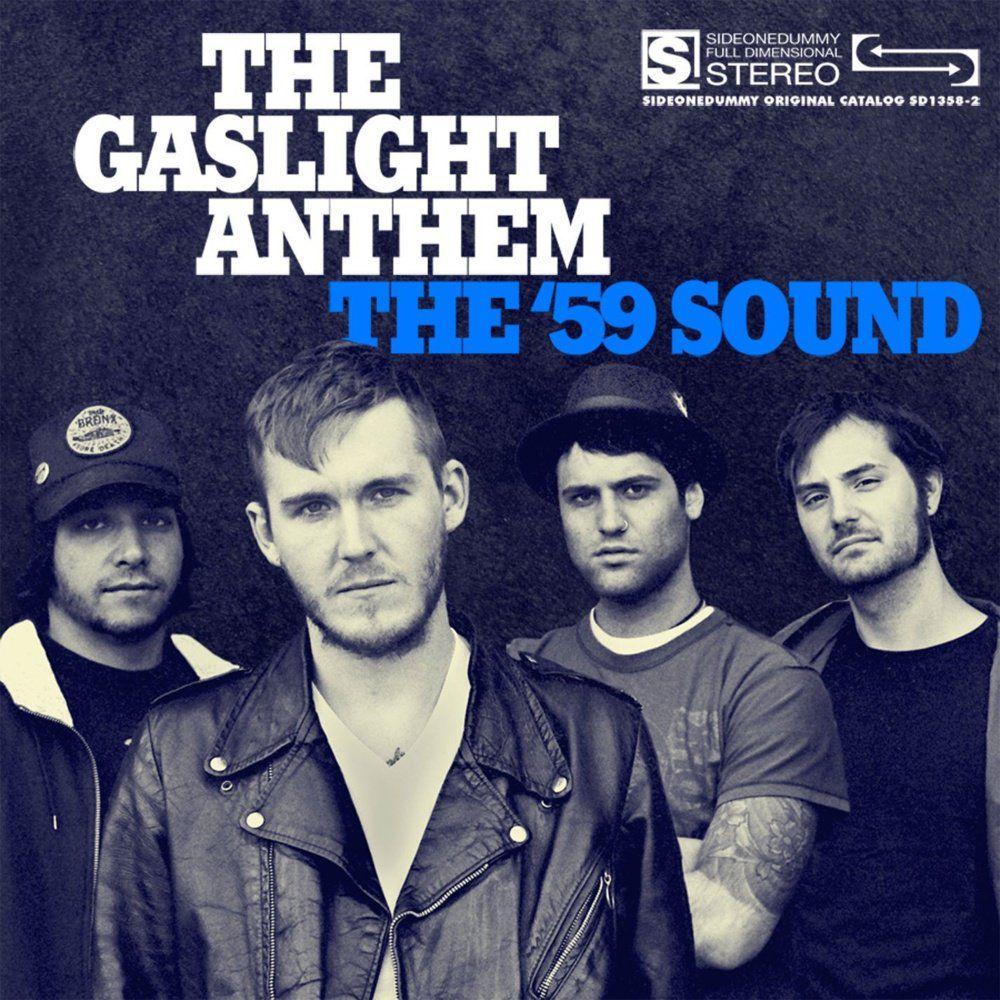

This Friday, SideOneDummy Records will release the original demo sessions for The ’59 Sound, a glimpse into the band’s first stab at a record that would take on meaning few imagined. The album was a follow-up to their 2007 debut, Sink or Swim, which had been adored in basements around New Brunswick but rarely heard outside the insular world of punk rock. Even as the interest around the group began to build, the rewards were modest. When Gaslight played a packed show at the Iron Monkey in Jersey City in July 2007, the pay was $75 and a case of beer. Their touring schedule was constant, both as a way to scrounge up a fan base and to avoid paying rent. “I’d be excited to do anything or go anywhere,” says guitarist Alex Rosamilia. “I was living out of a backpack.” The band took a show in Joplin, Missouri, on a whim after a Myspace message from a local high schooler. That night, they made dinner with the kid’s quesadilla maker and then crashed on his floor. It was the life of endlessly optimistic diehards holding onto the threads of a dream. “None of us were in very comfortable situations in our lives when this was going on,” says drummer Benny Horowitz. “There was this element the whole time like, ‘We’re doing this. We left everything to do it. And if it doesn’t work, we’re fucked.’”

Fueled by that urgency, The ’59 Sound turned into an unlikely triumph that eventually received a blessing from the Boss himself. A hat tip to the history of American songwriting, anchored by the drumming of a hardcore lifer, tinged by the sounds of classic soul, The ’59 Sound is an album of disparate influences that makes sense only when you hear it. The result, even 10 years later, is a record that endures. So while you’re wondering which song they’re gonna play when we go, here’s the complete oral history of The ’59 Sound.

I. “A genuine, genuine little masterpiece”

Joe Sib (cofounder, SideOneDummy Records): “The ’59 Sound” affects me and affects people emotionally. There’s something going on with the chords, along with Brian [Fallon], the production, that gets through all the bullshit in everyone’s fuckin’ head and goes to the core of who that person is and their heart and their blood and their family and their dad and their mom and their grandfather and their sister and who they should call. It digs through all [that], pulls it out and goes, “Are you ready? ’Cause I’m about to fuck you up.” And then it does.

Benny Horowitz (drums): Every band has one really special time. And if they’re lucky, they make a lot of music in that time. You can never get your youth back. You can never get the Fuck You of your 20s back. I think you can rediscover yourself and become something different, and that’s cool. But we can never do that again. It’s impossible.

Brian Fallon (lead singer): [People] thought I was talking about their lives. I love this because it’s talking about me. This is how I feel. I drive around in cars, hang out at diners, that’s our lives. We’ve got these dreams, and what do we do with those dreams, and what if we don’t get there?

Ted Hutt (producer): [The ’59 Sound] has that great ambiguity where it lets people in. People find themselves in that record. That started to click for me early on. It’s honest. It was a group’s honest statement. It’s real.

It had all the markings of a classic. Every song was great. There wasn’t any weak spots on the record. It was fresh and rich and newly discovered. A lot of spirit, a lot of soul. Those things have a tendency to last. The record is as fresh as it ever was.Bruce Springsteen

Fallon: The record doesn’t give you any answers. None of my best songs, throughout all my years, give you any sort of answer. They just say, “This is what happens, and I don’t know why.” I wonder what song they’re going to play when we go. I hope we don’t hear Marley’s chains. I don’t know, though! It’s questions, no answers.

Alex Levine (bass): Why did our second record, that was on a midlevel independent label, that [barely] charted anywhere, tap into some intangible thing in the atmosphere? I think it had to do a lot with the timing.

Bill Armstrong (cofounder, SideOneDummy Records): That record isn’t of a moment in time. It is a moment in time.

Dicky Barrett (frontman, the Mighty Mighty Bosstones/backup vocals): That album is very special to me. Not just because they allowed me to be a part of it, but because it’s damn good. From beginning to end. When I heard it completed, I thought “This is a genuine, genuine little masterpiece.”

Alex Rosamilia (guitar): [It] caught that thing that bands in the punk genre are kind of looking for, that sense of urgency mixed with a sense of nostalgia. I don’t think we were intending for it to do what it did. More than us made it what it was. I’ve always wanted to write something that mattered to other people. I never thought I’d actually do it.

Bruce Springsteen: It had all the markings of a classic. Every song was great. There wasn’t any weak spots on the record. It was fresh and rich and newly discovered. A lot of spirit, a lot of soul. Those things have a tendency to last. The record is as fresh as it ever was.

II. “We’re going to be here awhile …”

Sib: The way I remember it, there was a guy named Mike Pelak workin’ for us at SideOne. He had been a promoter, I believe, on the East Coast, loved hardcore, and he was friends with Benny.

Mike Pelak (SideOneDummy): I knew Brian and Benny [from] the local punk scene in New Jersey. Brian was in an old band called Lanemeyer, and Benny was in a band called the Low End Theory. One day, a friend from New Jersey was out visiting me, and he said, “Hey, have you heard Brian and Benny’s new band? They’re called the Gaslight Anthem.” I downloaded [Sink or Swim] and from the moment I heard it, I knew it was above and beyond.

Thomas Dreux (head of international sales and marketing, SideOneDummy): What would tend to happen in the office, there would be records that we all would agree on, and those records would get overplayed. Sink or Swim was definitely one of them.

Armstrong: I listened to Sink or Swim, and I was like, “Wow, this is really cool.” I wasn’t like, “What the fuck!” But I thought, this is really cool.

Pelak: They were playing in L.A. at the Scene Bar in Glendale. I just kind of made a silent decision that, “I’m going to walk them into the office.” It was that scary thing of, “Am I being an asshole right now, doing this?” I’m just kind of thrusting this band on Joe and Bill. But it couldn’t hurt.

Rosamilia: It was the coolest thing ever at that point, a label showing us around the office. They had nachos just there, ready to go. Joe said something like, “Tuesdays, we nosh on ’chos.”

Levine: I remember walking in and seeing gold records — a gold Flogging Molly record and the Warped Tour compilation. It was just like, “Holy shit, they’ve really carved out a niche in punk rock — and music in general.”

Fallon: The first thing you see is that Flogging Molly has a gold record. How does Flogging Molly have a gold record? Flogging Molly’s not on the radio. Flogging Molly’s not on MTV. Flogging Molly’s not a band where you could go to the mall and ask 20 kids, and they’d know who they are. We thought that was awesome. I’m not the sort of person who longs to be a rock star and hear Wembley Stadium cheering my name. I just want to make music that makes people feel good, and I’d love it if I could pay my bills off it too, while never losing that balance. Walking into SideOne, we saw that the balance was possible for the first time.

Pelak: I feel like that bold move of just walking into the office was enough for Bill to say, “OK, we’ll take the trip out [to the show] tonight.”

Armstrong: The Scene Bar, in Glendale. They were not anywhere near [being] the headliner. That place maybe fit a couple hundred people, but it was pretty loosely filled. I went out there with a buddy of mine and I said, “If the band’s no good, we can go after two songs.” Then seriously, halfway through the first song, I looked at him and said, “We’re going to be here awhile.”

Sib: He comes in the next day and says, “Dude, I went and saw Gaslight Anthem last night. I don’t know, man. There is something there.”

Armstrong: What jumped out at me more than anything else was the tone of Brian’s voice. It was the first thing that hit me. The tone combined with a very real gift. It is one of those things that’s hard to put your finger on and put into words, but it’s very easy to see when it shows up in front of you.

Sib: That day, they were playing in San Diego, and when he tells me this, it’s like 10 in the morning. I coulda seen ’em a mile from my house, but I’m like, “God, I gotta go to San Diego, fuck.” And this is what’s funny: If it wasn’t for surfing, we might not have started working with Gaslight Anthem. I go, “You know what? I’m gonna run back up to my pad, grab my board, and I’ll drive down.” That night they played, and they fucking just killed it. I remember two songs in I was like, “Fuck yeah, it’s on. It is on.”

Levine: That fucking show was so bad. We sucked. We were terrible. I’ll never forget how bad we were. And I remember Joe talking to us back by the trailer and saying, “You guys have that intangible thing, but you need to work on your performances.” That was something that stuck with me. He didn’t care. I took that to heart. He was a frontman in a band that we grew up listening to. Even if we don’t sign with these guys, that’s worth its weight in gold, to hear the singer of Wax say, “You guys have what it takes, but tighten up the bolts here.”

Sib: It’s probably midnight and I’m supposed to go to my hotel room to go to bed. I go to the hotel, and I’m just so amped up from seeing them. I’m like, “I wanna work with this band, I wanna work with this band.” I try to go to sleep at 1, 2, 3, 4. And finally at 4 in the morning I’m like, “Fuck it, I can’t go to sleep.” I load my board up, throw it back in the Prius. I’m jamming up north and at like 4:30 in the morning, I call Bill and say to him, “Dude, we gotta work with these guys.” And first thing he says to me, “Yeah, well you and everyone else wants to work with them.”

Fallon: At the time, we were kind of being courted by everyone. We were taking a lot of meetings. We sat down with one major label, just so we could say we did it. We were very ignorant at the time on the business side. Everything ran on instinct. The main thing about SideOne that was different was that with everyone else, it seemed like you were stepping into business. We didn’t really want to be in business yet. That may be foolish because it is the music business, but we weren’t quite ready to put on suits. We wanted to find a way that felt punk rock, ethically, and also felt viable for a life where you didn’t have to go work 30 jobs when you’re off tour. With SideOne, we sorta saw that. We knew they could nurture that concept.

III. “It came flying out of my hands, a strange bolt of lightning.”

Hutt: [We would] share playlists [early on]. It was a lot of Wilson Pickett, Sam & Dave, Otis Redding, Arthur Alexander. Amongst the Americana, there was a passion for late ’50s, early ’60s soul. I think it’s important to stay immersed in what you love. Subconsciously, it finds its way into what you’re doing.

Fallon: It was probably similar to what I’m listening to now. Definitely the early E Street Band stuff. A lot of soul records; Sam Cooke, Otis Redding. And the girl groups, the ’60s girls groups; those were the ones where I would tell [Ted], “These are the best songs in the world.” The Supremes, that kinda thing. We just tried to put it together and make it part of what we do.

Horowitz: We were trying to sort of interject kinds of music that didn’t really appear in punk rock. How can we challenge ourselves to make something that feels like Sam Cooke in a punk rock song? How can you deliver that?

Rosamilia: We were trying to look at it from a more Motown standpoint. Not look at our band as a punk band, but look at our band as a soul band playing punk songs. And if that was the case, I always thought I’d be the horns section or backup singers, as far as arrangement goes; the rest of the Temptations or the Ronettes.

Hutt: There were things in there that came from such different worlds. I never felt like anything was being ripped off. I think they were genuinely the sort of things that the guys grew up with. Alex’s guitar was immersed in Britpop shoegaze music. Brian was more classic. It felt like a long shot that those two elements could live in the same room, but they absolutely did, beautifully. It was the fusing of two worlds that were a million miles apart.

Fallon: I was working on this Fender Bassman amplifier that was built in 1959. I discovered that was the sound they were using on all those Sam Cooke records and Elvis Presley records. Bruce used one. It seemed to be a common thing. It was like, “Well, if all these records are recorded on this one amp, and if I can get that sound, maybe I can get some of that magic.” I was a firm believer in the magic of things. And I obviously couldn’t afford a real one, so I would build it.

There’s things that are set in your life, and that was one of those. I didn’t do much. I just reached out and grabbed it. I don’t know. I think I was waiting for it. I was waiting for it for a very long time. And I just caught it sitting on the floor that one time.Brian Fallon

Andy Diamond (friend): That amp is all he wanted to talk about for a couple months, that’s for damn sure.

Fallon: I bought a reissue of it, and I ripped everything out. There was nothing left. Just the wood frame. I took it apart and rebuilt it as it would have been in the ’50s. I went to different electronic stores, and I had to look on forums to find the parts. I got it part by part. Every couple weeks, I’d add a new one. I ordered the choke — it separates the voltage and smooths it out — and when they were rehearsing, I took a soldering iron, opened it up, and did the thing.

Rosamilia: It looked like the back of a TV from the ’40s. Just a bunch of vacuum tubes and a transistor and a bunch of pieces attached to a giant board. We’d go down to practice, and it’d just be upside down on the arms of a chair so it would sit better. He’d be working on it up until me and Benny showed up.

Fallon: I was building it at the same time that was I was writing [the song] because I was trying to find an amp to get the sound that I wanted. I was writing on paper, “The ’59 Sound.” I had the title, and I was scratching at it. When it came, it came in one chunk. Music and lyrics all right there. It came flying out of my hands, a strange bolt of lightning. It took maybe 15 minutes.

Rosamilia: [When he played it for us] it all came out at once: “This song is called ‘The ’59 Sound’ because …”

Fallon: [The amp was] the material version of what it meant to me. The intangible thing of “The ’59 Sound,” it didn’t mean anything about the ’50s. I didn’t imagine people banging on jukeboxes and Fonzie and all that. I’m not interested in any of that. To me, it reminded me of my grandmother and a time where simpler things were valued more. Friendships, relationships, and that kind of thing. There weren’t so many distractions. You didn’t have so many goals. Now, a kid grows up, and he could be anything. That’s great, but it’s also very daunting. Because which one of the anythings do you be?

Kevin Custer (video director, “The ’59 Sound”): He was describing that basically there’s a sort of unique space that exists when you take an object like a baseball and throw it up in the air. There’s a force, thrust, that’s acting on it. Then when it comes down, gravity is pulling it to the earth. But for a fraction of a second there’s nothing acting on it. It’s sort of in that frozen state for a fraction of a second. This song is like this transition point between childhood and adulthood that just happens, and you’re not aware of it.

Rosamilia: Brian kind of played it once, just him playing the guitar. We ran through it, and in like 25 minutes, it was done. The third time we played it, it would have been recognizable to you. It didn’t change that much. The song gave us the vibe of the record, the title of the record, all of it right then and there.

Fallon: There’s things that are set in your life, and that was one of those. I didn’t do much. I just reached out and grabbed it. I don’t know. I think I was waiting for it. I was waiting for it for a very long time. And I just caught it sitting on the floor that one time.

IV. “This is how he gets through life. This is his sustenance.”

Levine: We did a tour opening for the Loved Ones on our way out [to L.A.] to record. Me and Brian were huge fans of that first Loved Ones record. We wanted to play music like that. When they took us out, it was a cool thing.

Dave Hause (The Loved Ones): We took them out on the tour in 2008, and they were great. They were a little wet behind the ears, but I could tell there were some really great things about the band. And a lot of that was Brian’s writing. I said, “Oh man, he’s onto something here.”

Joe Gittleman (A&R, SideOneDummy/bassist, the Mighty Mighty Bosstones): [At a show], I went down to find out what time the sets were and chatted with the band a little bit. Brian was sitting in the back of the van with a tape recorder and he was working on tunes. It was kind of that mode. And I thought that was cool. It’s like, if I had been his age on tour and I was in the van during the show, it wouldn’t have been good.

Hause: The Loved Ones were doing well, but we were partying like crazy, doing a lot of drugs and drinking a lot. But [Brian] was focused. That hit me: “This kid really seems to want to prove it.” There were maybe 19 people at our show at Jack Rabbits in Jacksonville. That show was so shitty. Brian apparently went out to the van and was working on [a song] as we drank ourselves through the minor embarrassment.

Rosamilia: “Even Cowgirls Get the Blues,” I wrote that riff Day 1 of the Loved Ones tour at Black Cat in D.C. I showed [the song] to Brian, and he came back to me a couple days later with some stuff and we worked on a bit more.

I was like, ‘Holy shit, this tent is really busy. And this is the little band we took on tour like six months ago.’ I couldn’t quite understand what was happening, and then they played ‘Great Expectations.’ It was just … damn.Dave Hause, the Loved Ones

Fallon: Rosamilia had this guitar riff that you hear at the beginning of “Cowgirls.” And he was kinda like, “I just learned this, what do you think about this?” We were outside standing in the parking lot, and he would just play it over and over again. I figured out what chords were following the riff. Then I just said, “All right, you go away.” I wrote out all the lyrics and the all the melodies and was like, “Alright, cool, there’s one down.”

Horowitz: I’ve never met anyone, until I met Brian, who was so singularly focused on the one thing he wants to do. That is just what this guy does. Brian plays guitar, writes songs, performs them, and writes more. This is how he gets through life. This is his sustenance.

Fallon: Every band would drink and just hang, and I wasn’t really into it. I had to find my place. It’s getting loud, and the revelry’s about to start, so I’m gonna go sit in the van because I’ve got work to do. I knew we were a couple weeks out, so I’d just be like, “OK, later, I’m gonna go write a song.” I’m a firm believer that if it’s not taking you toward your goal, it’s taking you further away.

V. “We rode a fever out of Austin …”

Levine: The journey out there was one of the most fun times I’ve ever had in my entire life. I wish we had a videographer with us. Something special was happening, and being in the middle of it, you couldn’t really feel it.

Horowitz: South by Southwest was our last show before going to L.A. to record “The ’59 Sound.” It was one of the first times Hot Water Music started playing together again. It was an amazing bill, and we were so stoked to be on it. Andy Diamond had a very good friend named Julie in Austin, and she had this nice house, and a pool. She was always down for people to stay there. It was the best place to stay on tour.

Julie Lack (friend): They didn’t have two nickels to rub together, and I loved hosting people. I had homemade cookies and beer, and everyone was over here doing laundry.

Diamond: It was all you could ever ask for, especially when the money wasn’t coming in yet.

Horowitz: My ex-girlfriend actually came out to see me [in Austin]. From even two days before, she was kind of on a rampage. I was anxious before I got to town. Then she got there, and things were really bad. We played the show, and maybe about 20 minutes afterward, we broke up on a curb behind the [venue].

Diamond: One of the craziest breakups I’ve ever seen.

Lack: You bet your sweet ass it was a nightmare. While they were playing their big South By gig, she put all their shit in the front yard.

Diamond: Guitar cases, backpacks. And that’s back when your entire life was in your backpack.

Horowitz: Instead of going back home to that [situation], I was going to L.A. to record a record. It was an incredible head space to be in, truly. In retrospect, I don’t know if anything better could have happened because how much further it made me invested in the record, and the process, and the experience.

Diamond: [Levine] was so broke. We went back to Julie’s, not to drink or swim in the pool — we each took four or five beers from the cooler, put them in our pockets, and went back to the bar. Just to save money. It was Lone Star cans, and I had to make sure the bar sold Lone Star. Times were tough back then.

Levine: I pulled into Hollywood with zero, zero, zero dollars. The night before, I spent the rest of my money on alcohol. We were all broke, and I’m the one who spent my last $50 on booze. I remember I wanted a pepperoni Stouffer’s pizza so bad. Me and Brian always ate those. He eventually ended up giving me one of his: “You fucking asshole. Here.” It was like me settling my past life, and when we started The ’59 Sound, it started the rest of my life.

Diamond: There’s a line on “The Backseat”: “We drove straight on through the night, we rode a fever out of Austin, dreamed of California lights.” That lyric … when Brian sings, “We rode a fever,” he wasn’t kidding. He was so sick that day. He was about five shades lighter than he normally was, and the kid is pale to begin with. He was dripping from his forehead. Sick as a dog. That’s what that line means. And boom, they just shot off.

VI. “There was nowhere to go. There was nowhere to hide.”

Horowitz: When I imagine us going to L.A., all I think about is sun, and blue, and cool air and good weed and good food. Every physical memory sensor I have of it is super fucking California. It feels like a Beach Boys record.

Levine: I’d always wanted to live in California, but I’ll never forget waking up and being stuck in fucking L.A. traffic.

Horowitz: We were at the gas station after getting to L.A. I was driving, and this cab driver told us to roll down our window. He saw the plates and said, “Jersey, huh?” And he points at himself and goes, “Brooklyn.” He asked us what we were doing there, and then goes on this tangent: [in a Brooklyn accent] “You know what you do? You come here, make your money, and you get out. These people, you don’t want to live around these people. They can’t drive, and they don’t know their place.” That’s the one line I always remember. He’s this mythological creature from my past.

Dreux: They came in, and they stayed at a place called the Oakwood.

Horowitz: Not only did a very nice concierge-type person greet us: He had a British accent. So that’s just to throw it over-the-top cliché. And I’m messing around with the guy, “All right, we’ll try not to get kicked out of here.” And the guy, super dryly, basically said, “Sit down, sonny. Motörhead has an entire row of apartments here right now. There’s nothing you guys can do to get kicked out of this place.” Basically, it was, “Listen, you vanilla, rookie motherfucker. I’ve seen you come through the Oakwoods a thousand times.”

Rosamilia: It was a one-bedroom with two twin beds and a couch. I just slept on the floor the whole time. The idea that there were five of us in there for a month didn’t bother me in the slightest. Remember, I was homeless. Now I had a refrigerator. I could buy food and leave it for an indeterminate amount of time. I remember going to Ralphs for the original shopping trip.

Levine: SideOneDummy gave us $500 to stock the refrigerator.

Rosamilia: We had got all the food we needed, and there was a little money left over. And the only things I can remember buying were a handle of Smirnoff and Stripes on DVD.

Levine: He forgot the mini-keg of Heineken, which was gone in a day.

Hutt: We had a pretty tight schedule to get [the album] done. The preproduction part of it is very important to me, so we booked into a place in Eagle Rock and set up and starting going through the songs. The goal was that after the 10-day period we had in there, we could play the album from beginning to end. We wouldn’t be searching for any answers in the studio.

Fallon: [At night], I’d be writing at the kitchen table trying to finish the record. It was chaos. I sat at the table while the TV was on, somebody was banging around in the kitchen — and when I say the kitchen, I mean the area to my right. There was nowhere to go. There was nowhere to hide. It was insane to think you could work under those conditions. That’s strictly a young person’s thing. You’ve got to be burning with excitement, or that’s not going to work. I wrote “Meet Me by the River’s Edge” one night, “Here’s Looking at You, Kid” another night, “The Backseat” another night, and I think “Old White Lincoln.” I wrote four of those songs right there, at the table, in a week. That seems impossible right now.

Hutt: It was a fairly quick assessment when we started working together, that he was super talented, and you could sense it. If there was anywhere that he wasn’t quite as profound as he should be, [I’d say] let’s look at it again and see what we can find. Let’s dig a little deeper.

Fallon: I had written another chorus to [“High Lonesome”], and I went in with Ted. We were playing the song, trying to work on it, and it just wasn’t happening. And I was like, “Stop. This is what I want it to be, and this is what I want it to say. I’m taking a little nod to the Counting Crows. I know that’s not a big punk band, but I don’t care.” It’s not, “Maria came from Nashville with a suitcase in her hand” because I’d run out of lyrics. I was trying to make a point. I was writing an answer to that lyric that Adam [Duritz] wrote. I was saying, “She’s looking for a boy who looks like Elvis.” And I’ve always kinda wished I looked like Elvis. Not literally Elvis, but someone better looking than me. That’s where that theme kind of came from. It’s almost like you’re arguing with yourself in the chorus, and by doing it, you’re telling more of the truth.

Hutt: He would organically sample these songs. These specific songs formed the artist that he would become. I thought that was fantastic.

Fallon: I just threw all that stuff in there because I want to define us without letting other people define us. So I did it through other songs. And also to give a nod to … I’m not trying to invent something here. I’m trying to carry on a tradition of songwriting.

Hutt: There was something very authentic, believable. For me, it’s ultimately about whether it’s coming from the heart. And I got that from him.

Springsteen: It was this fascinating combination of elements. Punk music, elements of soul music, and some of the imagery had a kindred spirit that worked its way in there. It was this incredibly fresh music that had the slightest spark of some of the things we did, and it was really quite wonderful. You never know where some of your influences are going to go. That’s what you do it for. You do it so you can pass it on, and to see it come back around in a beautiful way.

It was a one bedroom with two twin beds and a couch. I just slept on the floor the whole time. The idea that there were five of us in there for a month didn’t bother me in the slightest. Remember, I was homeless. Now I had a refrigerator. I could buy food and leave it for an indeterminate amount of time.Alex Rosamilia

Horowitz: Ted probably found the most open Gaslight Anthem that we’ve ever been as far as taking people’s ideas and stuff like that. I think Ted’s biggest influence, really, was just the way that he was able to frame lyrics and songs and work with Brian intimately on that stuff.

Fallon: [“Here’s Looking at You, Kid”] is cool because it’s not aware of itself. I think the moments that I’ve written best are the moments when I’m not being aware of myself. You have to know that the joke is, a little bit, on you. It always will be. And that’s OK. It’s fine. You have to allow yourself to be sincere. That’s what a lot of people are afraid to do. When you strip away all of the preconceived notions about whatever you’re supposed to be and just write a song, there’s a purity to it.

VII. “What do you mean ‘the order’? We haven’t recorded it.”

Rosamilia: [Ted’s] ideas are ideas that I still use to this day writing songs. They’re things I still hang onto. There was a song where the bridge eventually became the chorus to “Old White Lincoln.” He said, “This is too good to be a bridge. You need to repeat this.”

Fallon: We did not play well. We were not grown-up musicians at the time. We were people banging on instruments. Ted turned us into the beginning of musicians.

Rosamilia: He had a Zemaitis, which is basically a guitar that’s made entirely out of metal. It’s a different tone. It sustains longer because the metal vibrates. It’s heavier than shit. We played it through a ’50s dictaphone recorder with a reel, and a weird plug for the microphone. That’s what that distortion sound is, just plugging the guitar into that and being blasted through a two-inch speaker.

Hutt: Left to his own devices, I think Alex could have lost himself in [that studio].

Rosamilia: I’m a sucker for toys. They had a Wurlitzer there. There were so many things in there I wanted to use that they were like, “You need to slow down, guy.”

Ryan Mall (engineer): There are so many sounds on there that aren’t music, necessarily, that kind of play into the authenticity a little bit. Whether it’s the car starting on “Old White Lincoln,” whether it’s the needle dropping on “Great Expectations.” I feel that that was Rosamilia’s idea.

Rosamilia: I stole that from “Hopeless Romantic” by the Bouncing Souls. At the time, vinyl was just starting to get cool again. I was like, “Yo, we should just drop it like that.”

Hutt: I had an old Dobro, and Alex picked out the [guitar] part on that. It sounded really cool, but we wanted to go a little further with it. We actually brought a turntable in, put the beginning of a record on it, and dropped the needle on it. It actually is the sound of a record starting.

Gittleman: I remember coming by one day when they were recording the car that was at the top of “Old White Lincoln.” That was actually Joe Sirois’s car. And it wasn’t a white Lincoln. It was a Ford Thunderbird.

Mall: We actually dragged a microphone out into the parking lot.

Hutt: There was also a slapback [on Brian’s voice], and that sort of originated out of that time period. I love that sound anyway, but it seemed like the right thing to do with the vocals. Once we put it up and listened, we said, “Yeah, let’s do that for this record.”

Fallon: I remember the tape echo being a big thing. People were like, “What?” and I was like, “Yeah, the tape echo. What’s the matter with you? Have you never listened to the Clash, or Bruce Springsteen, or literally any band?” This is a thing. It’s the whole sound. But it wasn’t common for a punk band.

To me, what makes that shit special is that it’s exactly what needed to happen then. Sometimes I get terrified about the prospect of writing new music, and it’s not the fact that I don’t think I could make something better than ’59 Sound. It’s that maybe you can’t capture that moment again.Benny Horowitz

Armstrong: It’s a pretty big commitment, and it’s one of those things that honestly, now it just seems like genius. But at the time I wondered if that was gonna bug anybody.

Sib: When I heard “Great Expectations” I was like, “Cool, it has this quick slapback on his vocal for the first song. That’s cool.” And then the second song starts and it’s still there. And then the third song, it’s there. And I’m like, “Wow, is this an ongoing theme or something?”

Fallon: That was Ted’s thing. He wanted constants. With a record, to establish a theme, you have to have constants. Every band in the world was using Marshall stacks and turning them up with gain everywhere, and you could barely hear what the guitar player was doing. We decided to go the complete opposite way and recorded all my rhythm guitars with absolutely no distortion at all. And the vocals would have echo because that would anchor the song in soul music.

Hutt: It was a conscious decision to rehearse [the songs] in order. We wanted a record that felt like a story. We consciously decided when we worked through the songs to make that one flow into this one. We wrote a board up and created a sequence. The goal was, by the end of the rehearsal sessions, to be able to play the record from top to bottom as if we were going to listen. That’s pretty rare.

Rosamilia: We had what would end Side A, what would start Side B. You could listen to one side, and it felt like a complete thing. It wasn’t just, “Here’s our 12 songs from best to worst.”

Fallon: I had the bookends because I always viewed it as an album. I knew [we were opening with] “Great Expectations,” and I knew we were closing with “The Backseat.”

Rosamilia: We did “The ’59 Sound” in 15 minutes, and it felt awesome. But “The Backseat” felt bigger than anything we’d ever done before. For me, it was the most cinematic song we’d written to date.

Horowitz: It’s the bit at the second verse going into the bridge. The leaving Austin and going to California lines. I don’t know if it’s my memory of that time, or if it’s just one of those beautifully climatic parts. There are parts in classic rock where, it’s just, “Mmm. That was the perfect climax and mash of notes that just feels right.”

Levine: “The Backseat” is my favorite song we ever wrote as a band. The last eight measures of that song, if you could bottle that up and sell that … it’s a unique thing. We close with that song every night, and whenever we get into that outro, the hair on my arms stands up. I’ll always look out and say, “Holy shit. This is fucking awesome.” Something about that song, that is what my band is to me.

Armstrong: Brian really had a vision. He knew what he wanted to do. Some people go into the recording studio to build. Let’s try this, let’s try that. He really went in knowing.

Sib: This is the craziest thing I’ve ever had happen. I walk into the [preproduction] studio, and he says, “Look, here’s the order of the album.” And in my mind, I’m like, “What do you mean ‘the order’? We haven’t recorded it.” The chances of all these songs makin’ the record, the chances that you know you’re gonna start it with this “Great Expectations” and that you’re gonna end it with “The Backseat” … I remember it being kinda like, “I’ll let you run it, but it’ll never turn out that way.”

Fallon: Joe was very shocked by that. Not only did I tell him, “This is the order of the record,” I also told him, “I know [that ‘The ’59 Sound’ is the first single].” Joe was the radio guy. He was pretty established. I was 27, and this was my second record. And he was like, “So what do you know about singles and radio?” I told him, “I don’t know anything about singles and radio, except for the fact that I’ve listened to it my entire life. And I know that this song rules, and I don’t care what anyone says.”

Sib: All of a sudden the record gets done and sure enough, it was in the same order that he played it to me in the studio. [My first thought] was “‘The ’59 Sound’ is fuckin’ huge. This song is a fuckin’ game-changer. This is a single. We gotta go with this fuckin’ right now.”

VIII. “You had goose bumps, ’cause like, ‘This is gonna happen.’”

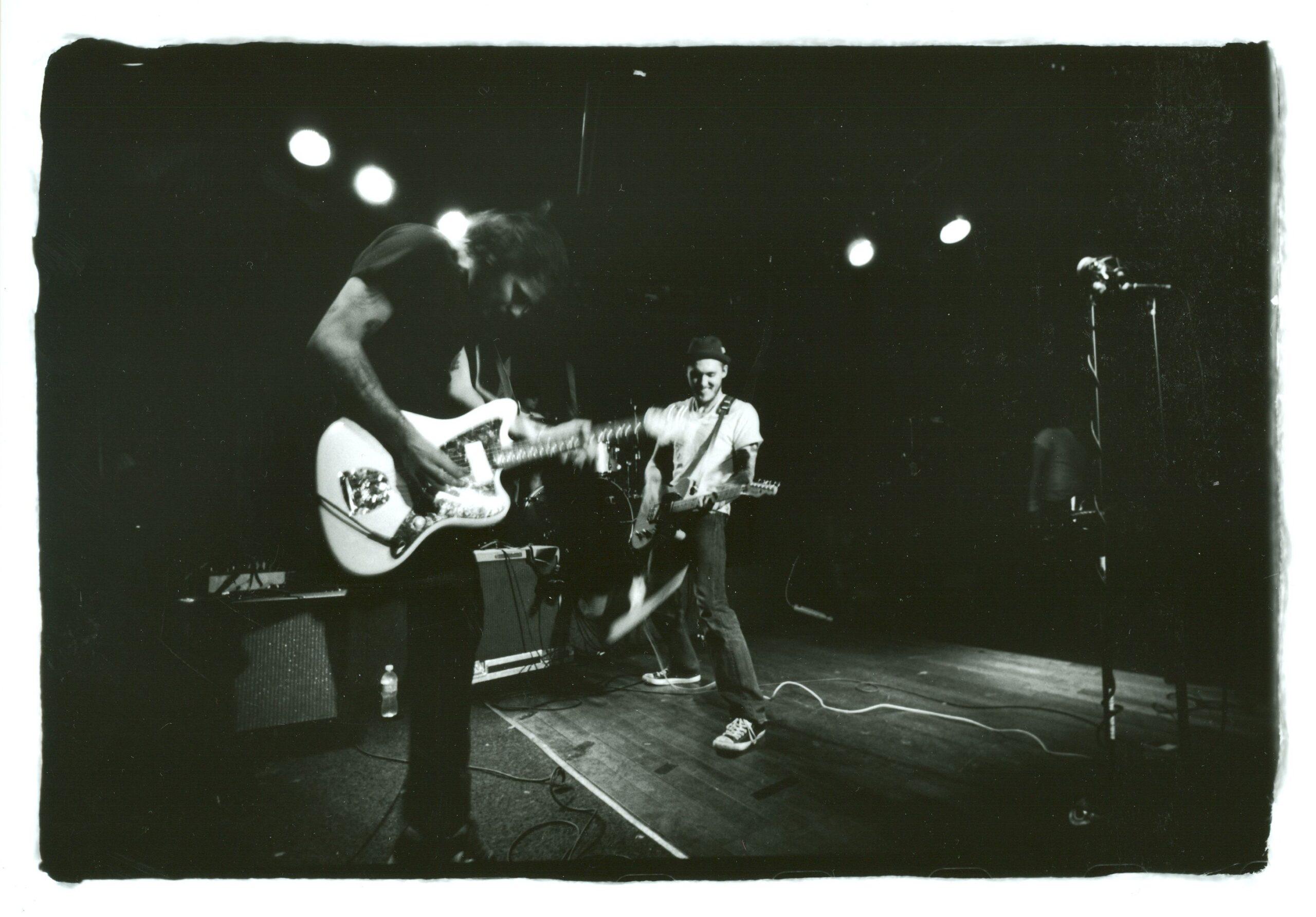

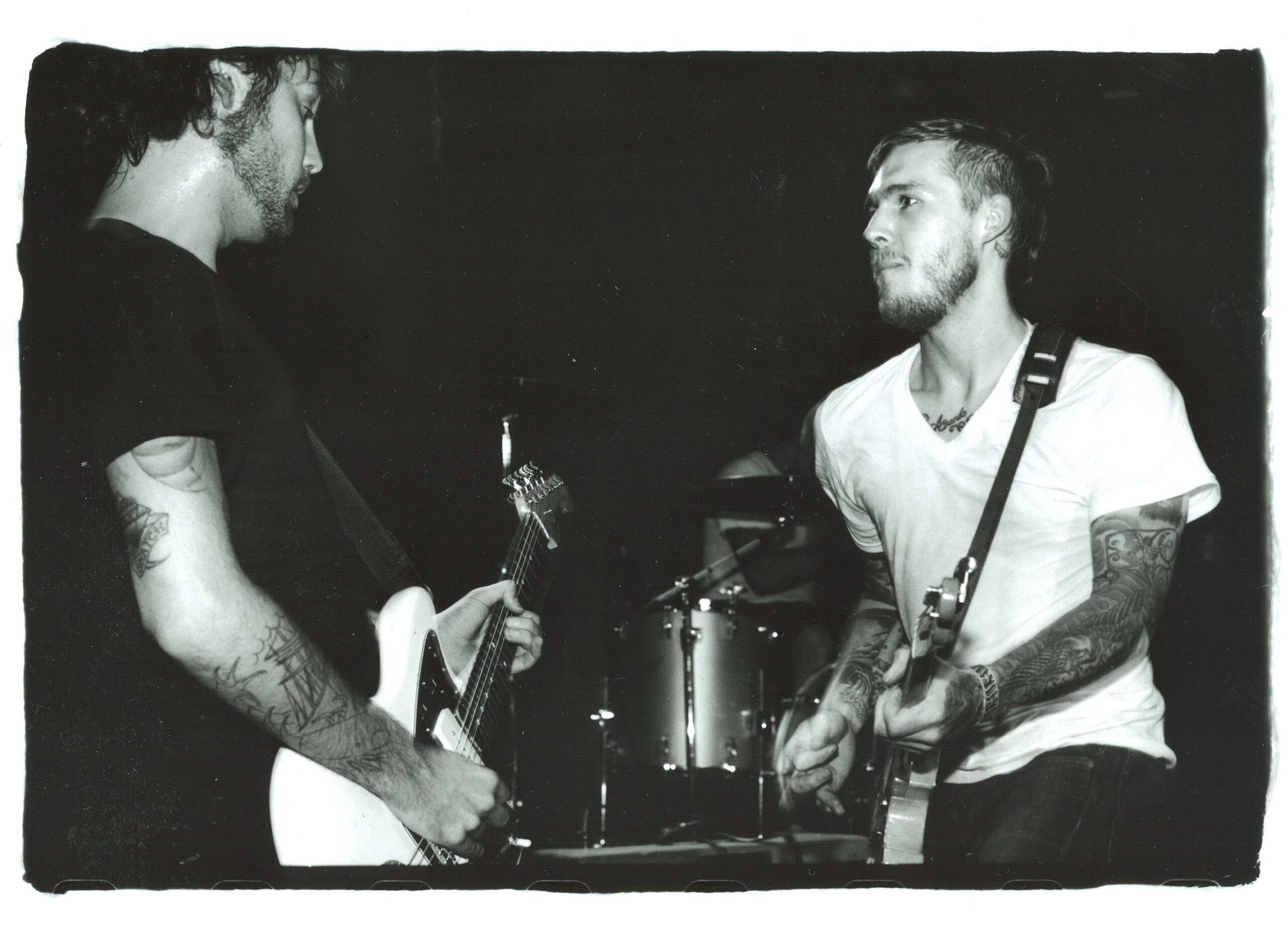

Eddie Eastabrooks (head of domestic sales, SideOneDummy): After they finished recording, they played at the Knitting Factory on Hollywood Boulevard. It was probably 100, 150 people.

Lisa Johnson (photographer): There was nowhere I could stand without getting kicked in the head.

Eastabrooks: They played “The ’59 Sound” [for the first time], and it went over so good. You had goose bumps, ’cause like, “This is gonna happen.”

Levine: It felt like we were about to go on our journey. We’d accomplished something that I don’t think we ever really thought was possible for us. We went into California a completely different band than we came out. We were ready to go and do it when we left. All the questions that might have been asked before were answered.

Armstrong: When we were “marketing” the record, when we would try to describe it to people, we used the words “modern classic.” They’re a modern classic band. They’re like, “What does that mean?”

Sib: It was 10 years ago so it was like if you get on the radio, it’s a big deal. Right away I went out there and started screaming and getting in program directors’ faces. I remember getting in arguments with people about it, because I was like, “If you’re not playing this, you’re out of gas.”

Armstrong: I remember the album got leaked a week or two before street date. It was a big deal with management. We had it up on one of those databases, and someone had hacked in and gotten it.

Johnny Bouchard (director of college marketing, SideOneDummy): People were freaking out over it, and part of why Bill and Joe think that the record did so well initially was because people got to hear it early and got excited about it and connected with it.

Eastabrooks: We put our presale up [in July], and it broke our store. We couldn’t handle the traffic.

Rob Roth (owner, Vintage Vinyl): I’d say for the first month, just on the vinyl, we probably did 700 or 800.

‘The Backseat’ is my favorite song we ever wrote as a band. The last eight measures of that song, if you could bottle that up and sell that … it’s a unique thing. We close with that song every night, and whenever we get into that outro, the hair on my arms stands up.Alex Levine

Jon Pebsworth (head of publicity, SideOneDummy): The press, everybody, they just loved them so much. It was really cool. That happened before the show started getting bigger, or the tours were getting better, or the record sales started really escalating.

Fallon: Everyone thinks about The ’59 Sound and how when it came out, it just blew up. That’s not really what happened. It came out and it got minor, minor press.

Emma Van Duyts (U.K. publicist): Kerrang! went from hardly having anything on the band at all to wanting to put them on the cover. Paul Brannigan, who was the editor over there at the time, I sent him the record and said, “I know you’re gonna love this.” He messaged me not that long after, and was like, “I’ve listened to this record like eight times already because I’m obsessed.” I was being a little bit cheeky and said, “Well if you like them that much, put them on the cover.” He called my bluff a little bit there. They were on the cover of Kerrang! before anything had really happened.

Sib: There was this love affair with Europe and the band.

Dreux: When they were in the U.K. they played at the University of London.

Ian Perkins (former guitar tech/current guitarist): That ULU show was supposed to be at the Barfly, but [it sold out too fast]. That was kind of the standard: Bands would come do the Barfly to get themselves known. I’d never really heard of a band that was supposed to be playing the Barfly jump it. They just skipped that whole entry level.

Hause: In 2008, we ended up at Reading Festival. We stuck around the next day for Gaslight. And there was such a religious level of anticipation for their show at like, noon. Whatever they had done with the press to elicit the fervor in England was phenomenal. I was like, “Holy shit, this tent is really busy. And this is the little band we took on tour like six months ago.” I couldn’t quite understand what was happening, and then they played “Great Expectations.” It was just … damn.

Sib: The first [U.S.] tour they did on that record was Rise Against, Alkaline Trio, and Gaslight Anthem opening.

Diamond: These venues were big. Gaslight was playing in front of a lot of people, even though they were on first. You’d have the diehards that would show up. I hate to say it, all due respect to Alkaline Trio, Thrice, and Rise Against, who are three great bands, but Gaslight Anthem would leave the stage, and there’d be blood on the floor. They were blowing these bands out of the water. They knew they had something to prove. That was the turning point on a national level. This was no joke.

Perkins: [The other bands] could see where Gaslight was going even if the guys in the band couldn’t. I remember one of the guys from Alkaline Trio being like, “Will you take me out on tour down the road?” I thought that was funny. They kind of realized later, he was half-joking and half-serious.

Eastabrooks: Ten months after [The ’59 Sound was] released, we’d sold about 70,000 copies.

Sib: I remember [before Glastonbury in 2009] we went out with the people [in London] that were distributing the record over there and we were all celebrating because the record had done so well, and it was coming in for a landing. And I remember we were all drinkin’, the some guy goes, “Do you think Bruce will play with them tomorrow?” And everyone laughs like, “I know, wouldn’t that be crazy?”

IX. “The people there were rabid.”

Springsteen: Evan, my son, picked up on the guys pretty early. He turned me onto them. He just said, “Dad, this a group to watch.” [Brian] and I were introduced at a show, and I mentioned that Evan really loved the band. We just got talking. He was living in Red Bank, and he invited us over to his house for a barbecue one afternoon.

Diamond: Brian had a keg of Budweiser in his garage, the red Solo cups you’d see at a party. Bruce is going to the keg like an ordinary guy. Bruce’s Range Rover was parked bumper to bumper to Brian’s car, which, when you think about it, is pretty symbolic.

Kyle Roggendorf (guitar tech/friend): I said to my wife, “I talked to Brian. Don’t freak out. Bruce is there.” And she goes, “What do I care? It’s not Jon Bon Jovi.”

Diamond: This was a backyard. So they really bullshitted about whatever Bruce Springsteen and Brian Fallon talk about in private.

Springsteen: We ended up being at [Glastonbury] the same year, and I went there early to see their show. At that time, they had a pretty good following. Their tent was full. The people there were rabid.

Fallon: We’re about to go on stage. All these cop cars show up outside our trailer, and we’re like, “Oh no. What happened?” [Bruce] just walked up and was like, “Can I play that song with you?” My first answer to him was not, “Yeah.” My first answer was, “Do you know it?”

Rosamilia: It was like three minutes before we went on stage. Our tour manager comes up and goes, “Do you have Brian’s backup amp on stage?” We said, “Yeah.” And she said, “That’s good. Because he wants to use it.” Ian’s like, “That’s fucking stupid. The regular amp is fine. I don’t even know if the backup amp works.” And then she said, “No, no no. He wants to use it.”

Perkins: Brian had come with a new guitar, a Les Paul Jr. that Gibson had sent him. He was still playing his Telecaster, and he wanted to play the new guitar for the show. I remember talking him out of it: “Use it as a backup and give me one show to get it ready.” [Springsteen’s people] asked me, “Do you have a guitar? He’s not bringing [one].” And the only guitar that we had was the one I just told Brian not to play. Now I have to give it to Bruce Springsteen.

Rosamilia: I remember walking back to the trailer. I figured I’d introduce myself before he stood next to me and played the guitar. Ten thousand shouting “Bruce” in your face is a daunting sound. People heard that and they came running from all directions. It went from half full to people spilling out of the tent.

Roggendorf: Brian called me from Europe. He’s like, “You’ll never guess what happened.” I go, “What?” He’s like, “Dude, Bruce just came and knocked on my door and wanted to play “’59 Sound.’” I’m like, “Shut up.”

I think people take snapshots, and the trick is, artists develop over time. You have to balance wrestling with and accepting that. That image of who you were when people took notice of you.Fallon

Sib: Next day, we’re hangin’ out at Hyde Park. All of a sudden Brian’s like, “Dude, Bruce is gonna come out [again].” SUV comes over, they practice the song, Bruce goes up on stage — boom, he plays, awesome. Then we’re hangin’ out, we think it’s a done deal. We’re celebrating, and then Brian comes and he goes, “Dude, Bruce just asked me to come out and do ‘No Surrender.’” I go, “Are you fuckin’ serious?”

Armstrong: We had no idea that Brian was gonna go out and do “No Surrender” with him. That was really the amazing thing. Springsteen’s [former] manager, Mike Appel, was there, and he was like “Well, this is where we see if people fold or not.” I’m like, “What do you mean?” He goes, “Bruce invites people up from time to time but not everybody can pull it off.”

Sib: He was so comfortable in the moment and in a moment where so many others, no fault of their own, could waver or crumble.

Fallon: It was what it always was, come to manifest. It was everything I was going for, and I knew this was my opportunity. It might be my only chance. For me, it was sheer and utter determination to not fail in front of those people. This might be my only chance to speak my voice and get my emotion across. I didn’t care who was watching and how many people were there. I didn’t even care what the E Street Band thought. Bruce invited me to do this thing and give me a chance to put my flag in the ground, and that’s what I’m going to do. And it was super scary because if you do mess up, you’re messing up in front of, essentially, the world. To me, the [actual] world didn’t matter, that was the world I was looking for. That was the world I was trying to reach. The people that would take an artist like Bruce Springsteen, look at him, and go, “I relate to that.” It was my future in the balance. I was going out there and representing everyone that I was working with. I was representing the band. I was representing Bruce in a way, and his taste. I’m representing a song. I’m representing my parents, who’ve allowed me to do this. I’m representing all of this.

Hause: He did it. For all of us. Maybe he has to lug around that cross, but he got to sing with one of the greatest singers and entertainers in the history of rock and roll. Bruce Springsteen is the guy, and Brian had a moment with him. Yeah, he gets compared to him, but who else gets compared to him?

Dreux: At that point, we must have sold 10,000–12,000 records in the U.K., which was 12 months in and it was respectable for a band that started from nothing. But we knew that, if something happened with Springsteen, it was going to open a whole new part of the campaign. The sales, I think, went up 300 or 400 percent the following week.

Fallon; Then it sort of exploded into a whole ’nother thing. That was the moment when I said, “Oh boy. Whatever we did before, it’s gonna be different now.”

Sib: The next day the record went to no. 1 [in the U.K.]; iTunes rock chart no. 1.

X. “Nobody knew how to handle this. It’s not like your friend broke up with his girlfriend.”

Fallon: I don’t remember if it was someone in the press or someone who worked with us — and they said, “What are you going to do now?” And they said it seriously. It wasn’t a joke. And I remember feeling sick about it. “How do you follow that up? [You] just sang with Bruce Springsteen, what do you do now?” I was never able to let that go. You know when someone says something to you when you’re a little kid, and it sticks with you? That stuck with me in a real negative way.

Rosamilia: Our demographic widened immensely. That’s when you started seeing older guys bringing their kids. Overnight, the whole family started coming.

Fallon: I think I noticed instantly this deciding line of “We like Bruce, and we don’t want anything to do with that.” On the other hand, I saw, “We like Bruce, and these guys are from the same roots as Bruce and carrying on this kind of tradition but adding this punk rock thing. And we love it.” There was this immediate divide. No one said a word, but it was like [ripping noise] — tearing the curtain. And you’re just like, “I didn’t mean to separate the room here.”

Horowitz: When people used to bring up the Bruce Springsteen shit, me being the maybe more fast, punk, hardcore element of the band, I was like, “You show me a fucking part like [‘We’re Getting a Divorce, You Keep the Diner’] on any Bruce Springsteen record. What the fuck are you talking about? I’m writing Strike Anywhere drum parts. I’ve never heard that on ‘Born in the U.S.A.’”

Rosamilia: I never had a problem with it. I always thought it was awesome. I just felt bad, because I was the only person in New Jersey who didn’t grow up as a Springsteen fan. But you want to compare me to Miami Steve? I’m OK with that.

Diamond: You almost felt bad for Fallon at a point. He was trying to do his own thing, but they were beating him into the ground with this Bruce, Bruce, Bruce. It was constant. It was like a machine gun. And then they started hanging out together. That probably didn’t help things. How do you give one of your best friends advice about Bruce Springsteen? Nobody knew how to handle this. It wasn’t like your friend broke up with his girlfriend.

Fallon: People go from celebrating your achievements — “Good for you guys” — then, all of a sudden, it seemed like there were more voices going, “Yeah, that’s all right.” Why is it now like you win or you don’t get anything? I thought we were doing this to do it and have fun. This is worse than a construction job. At least after that, the homeowner comes back and goes, “Wow, great job on the roof.”

Horowitz: Have we ever honed in on the aesthetic of our band better than we did then? Have we ever known exactly what we were more than then? Maybe not. But I wouldn’t have known it at the time.

Levine: I think that record defines the band, whether that’s good or bad. I don’t know if we’ll ever be able to trump that record. Technically, we’ve had “bigger” records on major labels, but it always comes back to that record. We have five fucking records. A song like “45” is technically the biggest song we’ve ever had, but nobody is talking about that. It’s very much, the Gaslight Anthem is The ’59 Sound.

Horowitz: As I went record to record, at no point did I think, “This isn’t as good as ’59 Sound.” That wasn’t a barometer for me. As a musician, as part of a group, The ’59 Sound isn’t necessarily the best I’ve ever played. It’s not necessarily the finest recording. It’s not necessarily the best of anything. To me, what makes that shit special is that it’s exactly what needed to happen then. Sometimes I get terrified about the prospect of writing new music, and it’s not the fact that I don’t think I could make something better than ’59 Sound. It’s that maybe you can’t capture that moment again.

XI. “The defining moment of who we were.”

Horowitz: When I hear parts of that record, it just never could have happened any other way. I think about it now, and people talk about it all the time. These recipes for bands and records. When I think about the variables about winding up in a certain place, at a certain time, with these certain people, and these certain songs … so much of that is out of your control. There were just so many things that had to go into it.

Hutt: It’s really a strange feeling of knowing you’re in the exact right place at the right time. That sounds sort of corny, but everybody involved was the person who was meant to be there.

Armstrong: How you feel about the record, how I feel about the record — it hit people. It hit people at a time where it meant something.

That record isn’t of a moment in time. It is a moment in time.Bill Armstrong, cofounder SideOneDummy Records

Barrett: I think if I was a 20-year-old or an 18-year-old guy and that record came out, that would be my the Clash, London Calling. That would be the important record of my life.

Fallon: We did what we were setting out to do and established where we were coming from and who we were as a band. I think that record was the defining moment of who we were.

Levine: If the four of us were sitting in a room talking about doing another record, we’re not talking about “Oh, American Slang” [or] “Oh, Handwritten.” It’d be, “Maybe it’s time to get back to the ’59 Sound.” And how do we do that? Is it something that’s even possible?

Fallon: There’s a time period when people take pictures of people. If you use Joe Strummer in London Calling: the black shirt on the boat; Mick Jones with the hat on. When you think of that whole thing, that’s the Clash. When Bruce got super famous, you’d think, “That’s the guy with the bandana around his neck. That’s Bruce.” I think people take snapshots, and the trick is, artists develop over time. You have to balance wrestling with and accepting that. That image of who you were when people took notice of you. For me, the good part about The ’59 Sound is the image portrayed there is not something I’m embarrassed of in any way as a 38-year-old. That sort of image and those songs, I don’t think I’ve said anything that I’ve grown out of.

Springsteen: It was simultaneously sparse and epic at the same time. It was a blend of things that was particularly original. The band had a unique sound. The ways the guitar blended, the way the riffs sort of melted into one another. It was epic songwriting disguised in this four-piece rock band.

Horowitz: [I’ve] heard 100 incredible albums, top to bottom with beautiful lyrics and songs and music that nobody gave a fuck about for whatever reason. You could strip this all back, and we could talk about 1,000 things, but so much of this is just dumb fucking luck. The idea that somebody who played like me could meet somebody who wrote like Brian could meet somebody that plays like Alex. Even that is just weird to me.

Fallon: I have a purpose for why I’m playing these songs again. And I think that purpose will be met, and again, it’ll be time to say, “OK, well what’s next?”