Take a Look at Him Now: The Many Lives of Phil Collins

After an extended hiatus that found him becoming more beloved, the crown prince of middle-of-the-road Top 40 has embarked on a farewell tour. Should he be celebrated as a pop icon or vilified as a grouchy opportunist?Phil Collins used to be Mr. Nice Guy.

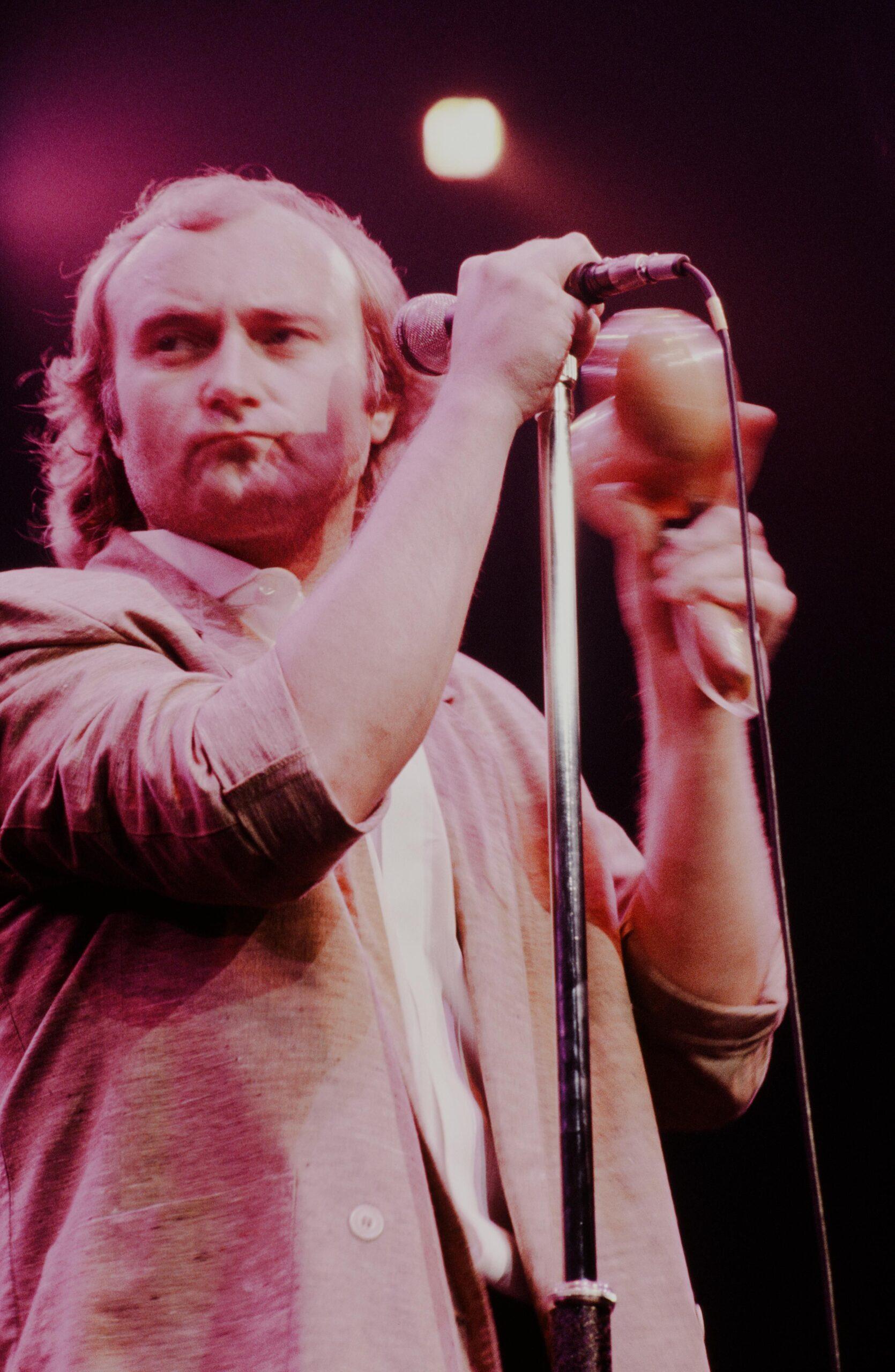

He was a pop star most people could agree on, whether it was your mother or Don Johnson. A ubiquitous presence in ’80s and early-’90s pop culture, this balding, middle-aged white man mugged for the camera on MTV—with push-up blazer sleeves and the requisite mullet, like one of the era’s midlevel road comics—and sang about relationships, politics, and something called a “Sussudio.” He was absurdly normal. If the middle of the road had an equator, it was Phil Collins.

But now, seemingly everything that once seemed innocuous back in the late 20th century has been given a Zack Snyder–style “gritty” reboot. These days, as he carries on with an extended farewell tour, Phil Collins is no longer a safe choice for dentist’s offices. He has instead been reimagined as music for monsters.

One of the most memorable scenes from The Assassination of Gianni Versace: American Crime Story, FX’s brilliant and underwatched 2018 miniseries, concerns Andrew Cunanan (Darren Criss) and a wealthy older man who thinks he has hired Cunanan to have sex with him in his Miami hotel room. What the man doesn’t know is that Cunanan is a fugitive serial killer who will soon murder the world’s most famous fashion designer. Cunanan has decided to torture his would-be john with some duct tape, a pair of scissors, and “Easy Lover,” 1984’s hit duet that Collins performed and cowrote with Philip Bailey.

The appearance of “Easy Lover” in The Assassination of Gianni Versace reveals new layers to Cunanan as well as the song. Setting aside the obvious logistical problems—why would Cunanan pack Bailey’s Chinese Wall CD for his cross-country crime spree, on the off chance that he would want to play it during an assault?—the song perfectly spotlights how the killer’s delusional megalomania fed his increasingly homicidal behavior. Criss’s ecstatic arm-waving to this frothy pop tune, moving in time with Collins’s titanic drum beat, while his prey slowly suffocates, is both chilling and darkly comic. The walls are closing in on Cunanan, but he will not be deterred from relishing his mayhem in the meantime.

As for “Easy Lover,” The Assassination of Gianni Versace teases out the song’s dark subtext, and then completely reinvents it. At the scene’s climax, Cunanan straddles his would-be customer, raising the scissors above his head. As he plunges the blade into the duct tape covering the man’s mouth, finally allowing him to breathe, Collins’s screaming vocal lifts on the soundtrack: “You’ll be down on your knees!” Whoa. Was that in “Easy Lover” from the beginning?

The Assassination of Gianni Versace made me think about another ’10s prestige drama that used a Phil Collins song as an instrument of dread. In the Season 2 premiere of Mr. Robot, an executive from E Corp stands on a busy Manhattan sidewalk with two large duffel bags loaded with cash. Soon, he will be instructed to take the money out of the bag and set it on fire, while dozens of stunned New Yorkers look on. As the scene plays out over several tense minutes, “Take Me Home”—one of four smash singles from Collins’s most popular solo album, 1985’s 25 million–selling No Jacket Required—is brought up in the mix. Again, Collins acts as a howling Greek chorus at the scene’s emotional climax: “I’ve been prisoner all my life,” he sings. Of capitalism? Of his own perilous grip on sanity? Do tell, Phil.

While “Take Me Home” has been interpreted as a song sung from the perspective of a man in a mental health facility, the popular video, which spun several times per day in MTV’s regular rotation in the mid-’80s, is a lighthearted travelogue, following a Hawaiian-shirted Collins as he flits from continent to continent on the No Jacket Required tour. Mr. Robot might have put “Take Me Home” in its proper context for the first time.

You can’t talk about Phil Collins’s sinister redux without mentioning American Psycho, the novel written by Bret Easton Ellis and published in 1991, and the American Psycho movie adaptation, directed by Mary Harron and released in 2000. Patrick Bateman also heard alienation and longing in Collins’s music, both solo and with Genesis, though Bateman believed Collins worked better within the confines of a group. “His solo efforts seem to be more commercial and therefore more satisfying in a narrower way,” Christian Bale observes in Harron’s film, while instructing two prostitutes he will later kill to act out his pornographic fantasies.

Harron and Ellis were satirizing the ’80s, but American Psycho now satirizes music criticism. In the past decade, Collins has inspired scores of think pieces without releasing much new music. His last record, the covers collection Going Back, came out in 2010. His most recent album of original material, Testify, was released 16 years ago. In 2016, he published a memoir, Not Dead Yet, and then there’s that farewell tour currently scheduled to continue this fall, when he will visit 15 major cities in the U.S. and Canada.

But otherwise he’s far less visible now than he was in his Reagan-era prime, when he racked up the lion’s share of his incredible sales statistics (more than 200 million albums worldwide) and was as big as any of the decade’s biggest pop stars.

And yet Phil Collins still has the ability to start arguments. While the man himself has largely disappeared from pop music, what he signifies about pop continues to loom large. He’s a go-to metaphor, a potent symbol for critical dissertations on taste, revisionism, the perils of overexposure, the emptiness of yuppie culture, the surprising popularity of blue-eyed soul among black audiences, the emotional resonance of drum machines, the nostalgic allure of vintage Disney soundtracks, and so much more.

The central question of Collins’s career remains the same: “Does this guy deserve to be hated?”

When Collins fell out of favor in the alt-rock ’90s as a dated hallmark of gated drums, plinky synthesizers, and Caucasian male dorkiness, the answer was “yes.” In the poptimist ’00s, when rappers and R&B singers earnestly covered his songs and a new generation of music writers emerged to dismantle indie exceptionalism, the answer was “no.” In the everything-at-once Spotify ’10s, when gated drums are back in fashion while Caucasian male dorkiness is all but banned from the most exclusive echelons of pop (except for quota case Ed Sheeran), the answer is … it depends?

Here’s what is tricky about Collins: He’s not just one thing. And the one thing you might like about him might very well be canceled out by something else that’s a total deal-breaker. In 2016, The New York Times published an “in defense of Phil Collins” piece centered on “In the Air Tonight,” a creeping ode to romantic holocaust distinguished by its “cavernous, brooding atmospherics” that “somehow encapsulated and suffused the ’80s,” including “the almost cartoonish specter of global annihilation; technological unease; white suits; fluorescent everything; and an unquenchable, cinematic emptiness that either evoked the end of history or a dodgy batch of cocaine.”

But how do you reconcile that “cavernous, brooding” classic with Collins’s second-most-streamed song on Spotify—nearly 116 million spins and counting—his bizarre, note-for-note cover of the Supremes’ “You Can’t Hurry Love”? That song, in its own unappealing way, also encapsulates the ’80s—the erasure of African Americans by white mainstream rockers, the bloodless sanitization of the ’60s, the boomer self-obsession, the extremely bad taste. Given the soulman affectations that Collins has leaned on time and again in his career, “You Can’t Hurry Love” is at least as representative of his music as “In the Air Tonight.”

There are those who would rather ignore Collins’s output from the ’80s altogether and focus solely on his prog years in the ’70s, back when Peter Gabriel was still the frontman of Genesis and Collins was merely one of the most technically gifted drummers in rock history, guesting on masterworks by Brian Eno and his jazz fusion side project, Brand X. For these dudes—yes, they are almost always dudes, and many of them have graying ponytails—Collins might as well have stopped making music after Duke, the 1980 LP that marks the beginning of Genesis’s world-conquering pop period and Patrick Bateman’s interest in the band.

If that’s a little too, um, rockist for you, perhaps you prefer to think of Collins as a forward-thinking record-maker whose spacious, booming songs remain favorites of Lorde and Taylor Swift. Though Lorde herself has also expressed a preference for Collins’s late-’90s Tarzan era, a common, not entirely ironic touchstone for many millennials and members of Generation Z.

Yes, there is darkness in Collins’s music. There is also lightness. He is serious and silly, profound as well as puny, impressive and imbecilic, with enough excellence and embarrassment to round out a dozen lesser careers. The urge to cast Collins solely as a hack who epitomizes everything superficial about his time, or as an underappreciated genius with untapped depths of meaning, stems from a tendency to mentally excise the aspects of Collins’s career that are contradictory, confounding, or simply inconvenient for forming a coherent opinion about the guy.

But to figure out and truly understand Phil Collins, you can’t leave anything out. Take a look at Phil now—the whole Phil.

Before spending hundreds of dollars on a ticket for the Not Dead Yet Tour—it has crossed my mind to see Collins in concert for the first, and probably last, time in October—I consulted YouTube for videos shot this spring by fans at shows in Mexico and South America. It was a wise, depressing decision.

He has looked better. Habitual back and neck problems, along with a 2017 head injury, have confined the 67-year-old singer to a chair on stage. (Otherwise he walks with a cane.) While he was never a kinetic mover on stage—this is a topic he has addressed in song—videos of Collins warbling his signature power ballad, “Against All Odds” in Peru or “Throwing It All Away,” a top-five hit for Genesis in 1986, in Brazil are … not good. His voice is weak. He seems feeble. I wonder whether he still belongs up there.

But perhaps this is the Phil Collins that the world demands at the moment. In the arc of our appreciation for Collins, we’ve reached “tragic figure” status. Collins himself played a pivotal role in this development, with a 2011 Rolling Stone profile that depicted him as lonely, angry, and even suicidal over a series of personal and professional tragedies—his divorces, the injuries that prevent him from playing drums (or, according to the article, wiping himself in the bathroom), and his history of substance abuse. But the focal point of the article is rebutting the criticism and mockery Collins suffered as an avatar for ’80s excess after his music fell off the charts.

”I don’t understand it,” Collins complains to Rolling Stone’s Erik Hedegaard. “I’ve become a target for no apparent reason. I only make the records once; it’s the radio that plays them all the time.” The part that everyone remembers from the Rolling Stone profile—aside from Collins’s weird obsession with the Alamo, and the photos of the Texas landmark that he insists show “orbs” denoting the lingering ghosts of 19th-century soldiers—is Collins’s sharing his disturbing fantasies about his own death, and the inconsequential public response he’s sure his actual demise would garner.

“I sometimes think, ‘I’m going to write this Phil Collins character out of the story,’” he says. “Phil Collins will just disappear or be murdered in some hotel bedroom, and people will say, ‘What happened to Phil?’ And the answer will be, ‘He got murdered, but, yeah, anyway, let’s carry on.’ That kind of thing.”

Given recent events, anyone who publicly proclaims that suicide has ever seemed like a viable option should be taken seriously, and regarded with gentleness and empathy. But revisiting the Rolling Stone profile seven years later, one can’t help but note the canny PR on display. Like one of Collins’s deathless breakup songs, the interview packages exquisite pathos and shameless bathos in equal doses.

In a different time, cynics might’ve scoffed at this so-called “exiled” pop singer sentenced to a quiet life in a luxurious Swiss villa outside of Lake Geneva, an otherwise enviable retirement destination for an aging emeritus superstar whose adoring fans still far outnumber his critics. (Collins has since relocated to Miami Beach.) But the Rolling Stone article effectively reset the way many former detractors thought about him.

“I distinctly remember paging through the story one night while taking a late-night subway home from work, and thinking: ‘Man, this is one of the most pathetic things I’ve ever read. Poor guy, maybe he did deserve better,’” observed critic Charles Aaron, in that New York Times piece from 2016 in which he was moved to reassess Collins’s career.

Collins’s lack of reverence for his own image, as well as the hits that made him famous, carried over to his memoir. This is also a good strategy for winning over the critics—flatter them by agreeing with some of their points. On the back of the book flap for Not Dead Yet, he says he wrote his autobiography so his epitaph won’t be “He came, he wrote ‘Sussudio,’ he left.”

“Sussudio,” of course, has been a staple of his Not Dead Yet Tour set lists, typically positioned in the encore right before the grand finale, “Take Me Home.” An improvised bit of quintessential “Totally ’80s!” nonsense that went to no. 1 in 1985—Prince’s “1999,” the song it ripped off, only went to no. 12—“Sussudio” has long functioned as both an albatross and money in the bank for Collins, who has nonetheless distanced himself from it repeatedly over the years.

But what if you like “Sussudio”? It’s fair to assume that the vast majority of Phil Collins fans probably don’t know about his post-’80s malaise, and continue to unequivocally enjoy his music. It’s likely that the people lining up to see him on the Not Dead Yet Tour never saw fit to reboot their view of him, because they still adore the Phil Collins they remember from their own pasts.

Like many people whose musical childhood education started with early ’80s Top 40 radio, Phil Collins was one of the first pop stars I ever loved. You really had no choice but to love him. He was inescapable in a way that seems modern by today’s standards. Back then, it was customary for an artist to milk a single album, using it to launch tours and spin off multiple singles, for as long as two years, and then disappear for three or four years. Now pop stars have to find a way to stay in your social-media feed in perpetuity. But Phil Collins was already doing that in the ’80s, rolling his latest solo album into the next Genesis album cycle, and then spinning several Genesis hits toward another blockbuster Phil Collins joint.

I didn’t discern Collins from Genesis. Either he was alone in his music videos, or he was joined by the tall guy with the beard and the other tall guy who looked like Phil’s accountant. No matter what, Collins to me was a comedic figure, like Robin Williams with less hair and more adenoidal romantic angst.

I don’t know whether people remember this aspect of the Phil Collins persona. But he really was funny, at least if you happened to be in the third grade. In the video for “Invisible Touch,” he sings into a drumstick like it’s a microphone. In “Land of Confusion,” he turns himself into a puppet. In “You Can’t Hurry Love,” he looks like one of the Blues Brothers. (The title of 1989’s … But Seriously acknowledges his comic image—Collins wanted you to know that his maudlin anthem about the homeless, “Another Day in Paradise,” was actually unintentionally hilarious.)

Did I think Phil Collins was cool? What does “cool” mean when you’re 8? I thought Huey Lewis was cool back then. Phil Collins made me laugh, so I thought he was cool, too. In the video for “Don’t Lose My Number,” my personal favorite, from No Jacket Required, he parodies extremely ’80s things (Indiana Jones, David Lee Roth) as well as things that don’t seem all that ’80s but are nonetheless recognizable archetypes (samurai movies, Westerns), even for a culturally ignorant child like myself. On a basic level, I connected to Phil Collins as I did to Mad magazine.

“My favorite pop males are the guys that sound like a combination of your boyfriend and your dad. That’s Phil,” Lorde told Marc Maron last year. For fans Lorde’s age, the kiddie-friendly gateway was 1999’s Tarzan, for which Collins wrote five original songs. The following March, Collins won a Best Original Song Oscar for “You’ll Be in My Heart.” One month after the Oscars, American Psycho came and went from theaters. But Tarzan ensured that he would be a cool dad and unthreatening boyfriend for yet another generation. He promised that you would be in his heart, but in reality he wormed his way into your heart. Being the father of young children has taught me that kids will one day be intensely nostalgic for Justin Timberlake’s “Can’t Fight the Feeling” and Pharrell Williams’s “Happy”—both of which are corny songs that were featured in soundtracks for animated films, and remain staples of every kiddie party I’ve ever attended. Phil Collins knew this 20 years ago.

Twenty-five years before the media made us feel bad for Phil Collins, music magazines were trying to puncture his “Mr. Nice Guy” image.

“The pop audience was primed for its own Cabbage Patch Kid, and Collins, with his catchy, smartly produced music, fit the bill: he was homely, and he sold,” Rolling Stone snarked in a deeply cutting 1985 cover story. It’s indicative of how the press perceived him at the height of his popularity—if you put this guy on your cover, you at least had to show that you weren’t happy about it.

Collins in retrospect conceded that his omnipresence in the ’80s made the backlash inevitable. His work ethic during the decade was almost pathological. In Not Dead Yet, he describes a particularly busy six-month period in the back half of 1984: “I produce Philip Bailey’s Chinese Wall album at Townhouse [Studios] in London; produce Eric Clapton’s Behind the Sun at Montserrat; write and record most of my third album, No Jacket Required; and take part in the recording of ‘Do They Know It’s Christmas?’ by Band Aid.” The following year at Live Aid, Collins famously appeared at both the London and Philadelphia shows, hopping on the Concorde for a transatlantic flight between gigs. Some viewed this as a sign of Collins’s hard-working populism; others felt he was an ego-driven glory hog.

For music writers inclined to view him with skepticism, Collins provided more than enough evidence that he deserved it. The Rolling Stone article opens with Collins complaining about recently losing to Stevie Wonder in the Best Original Song category at the Oscars—he was nominated for “Against All Odds” from the film Against All Odds, and Stevie was up for “I Just Called to Say I Love You,” from The Woman in Red.

”I’m disappointed that these things aren’t necessarily judged on merit,” Collins says.

On that point, he’s absolutely correct—“Against All Odds” is one of the great operatic ’80s breakup ballads and Phil sings the hell out of it, whereas even Stevie Wonder must know that “I Just Called to Say I Love You” is trash. But when Phil was pushed to explain why Stevie won, he had to go there. “Because he’s blind, black, lives in L.A. and does a lot for human rights,” he scoffs.

The story gets worse. He trashes “We Are the World” as a shallow exercise in limousine liberalism compared with its British counterpart, Band Aid—again, not necessarily a bad or even incorrect take, but at the time it made him look petty. (In the same graf, the writer even claims that Collins is a bad tipper, according to “talk among the valets at the Sunset Marquis.”)

The portrait that emerges is that of a privileged, self-absorbed jerk, a depiction that the magazine connects to Collins’s solidly middle-class London background. Born in 1951 to an insurance salesman father and a talent agent mother, Collins entered show business as a child actor, appearing as an extra in A Hard Day’s Night and in a production of Oliver! that played the West End. He started playing drums the same year, and at age 19, he joined a bookish rock band with biblically scaled delusions of grandeur that had just recorded its second album, 1970’s Trespass.

As the timekeeper in Genesis, Collins presided over some of the most stupidly complicated time signatures in rock history, a practice that continued even after Genesis moved past whimsical epics like the 23-minute “Supper’s Ready” and became a pop band. (Head to the nearest Guitar Center, find a drummer, and ask that person to play “Turn It on Again,” from Duke, just so you can watch her hands spontaneously burst into flames.)

After Gabriel left in 1975, Genesis slowly lost members until there were only three: Collins, Mike Rutherford, and Tony Banks. (This period is commemorated by 1978’s … And Then There Were Three.) The trio decided that the only way for the band to survive was to tour America extensively, to finally break into the world’s most lucrative pop market. Collins, who married his childhood sweetheart when he was 24, explained to his wife that he would have to be away from her and their two young children more often. She did not take it well. By the end of 1978, as Genesis celebrated its first gold album in the U.S., she had left him. By 1980, they were divorced.

The end of Collins’s first marriage provided the songwriting grist that would eventually establish his monster solo career, which launched in 1981 with Face Value—known critically as the most accomplished Phil Collins record, and commercially as “the one with ‘In the Air Tonight.’” Collins later claimed that he made up the lyrics to “In the Air Tonight” on the spot. The song’s narrative, about confronting the witness to a drowning, was inspired by the relentless ticking of the drum machine and, perhaps, the sorrow and frustration over his busted-up marriage.

An ongoing controversy in Genesis lore concerns whether Collins ever offered “In the Air Tonight” to the band. Banks said he didn’t; Collins has asserted over the years that he did and the band turned it down. In Not Dead Yet, he’s less certain, saying he doesn’t remember whether he offered the song or not. What can’t be disputed is the incredible value “In the Air Tonight” had in making Collins’s name bankable outside of Genesis. If he, say, forgot to play the song for Banks and Rutherford, it proved to be an advantageous mistake.

“The divorce left Collins demoralized, bitter, alone and, eventually, rich,” that ’85 Rolling Stone story notes, with an implied arched eyebrow. “In the Air Tonight” was an international smash, peaking at no. 19 in the U.S., though it was swiftly granted classic-rock-radio immortality. “Against All Odds” also came out of this period, though it wasn’t finished for another four years. (Director Taylor Hackford insisted that Collins rewrite the song to include the title of his Jeff Bridges–Rachel Ward potboiler, a remake of 1947’s Out of the Past that almost nobody remembers now.) Even the gleefully dumb “Don’t Lose My Number” originated from this painful yet creatively fertile time.

You’re usually allowed one divorce album before the world expects you to move on. But divorce albums became a cottage industry for Collins in the ’80s. His next solo LP, 1982’s Hello I Must Be Going!, includes several songs that Collins wrote after his ex-wife demanded more money in the wake of Face Value’s success, including the exquisite yacht rock of “I Cannot Believe It’s True.” There’s also the glowering “I Don’t Care Anymore,” a kind of son to “In the Air Tonight” that climaxes with Collins screaming at his invisible demons over enormous-sounding drum fills, less a moment of catharsis than a violent temper tantrum directed at a brick wall, a signature Phil Collins dramatic flourish.

The “divorce” mythology of Collins’s best-known songs presents another Rorschach test: Is he a depressive whose way with a catchy pop hook belies profound personal anguish, or an ambitious opportunist who leveraged his private soap opera for monetary gain? The quandary brings together unlikely bedfellows. Generation Tarzan and Ice-T vouch for Collins’s sincerity, while old-school rock critics and jilted prog-rock stans—mortal enemies otherwise—tend to subscribe to the latter view.

We’re used to pop stars having clearly defined roles—“queen” Beyoncé, “bad girl” Rihanna, “diarist” Taylor Swift, “genius” Kendrick Lamar, “gadfly” Kanye West. But Collins never was able to reduce himself down to a manageable, agreed-upon logline. He’s more like a choose-your-own-adventure story. How people feel about Phil Collins says at least as much about them as it does about him.

One of the more fascinating takeaways from Not Dead Yet concerns Collins’s jealousy of Peter Gabriel, the man he replaced as the frontman of Genesis. In terms of commercial success, there’s no question who was the more impactful singer—consider that in 1987, when Genesis had essentially been swallowed whole by Collins’s indomitable pop profile, Genesis was popular enough to play four sold-out nights at Wembley Stadium.

Even the mercurial Gabriel was sucked into Collins’s orbit. His mega-selling 1986 album So—the one with “Sledgehammer” and “In Your Eyes”—sounds like an upscale No Jacket Required, a quirky blue-eyed soul record buffed to a glossy pop sheen and sold with a battery of eye-catching music videos. But when So went quintuple platinum, reserving a premium spot in millions of freshly purchased CD players by the yuppie elite, Gabriel wasn’t derided as bland or craven. So was (rightfully) regarded as an arty pop masterpiece, a dazzling synthesis of Gabriel’s entrenched progginess with newfound emotional directness.

But weren’t Collins and Gabriel essentially doing the same thing as their careers reached their harmonized peaks? Collins seems to think so. And yet Collins and Gabriel aren’t on the same level in terms of esteem. While Gabriel was inducted in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2014, it seems unlikely that Phil Collins—no matter his influence or popularity—will ever get that kind of consideration.

“Hands up: I do envy Pete,” Collins writes in Not Dead Yet. “Even here at the height of my success it seems that, for every achievement or great opportunity that comes my way, I’m starting to accrue bad press as a matter of course. Pete seems to get good press equally automatically. It seems a bit unfair, which I appreciate is a pathetic word to use in this context.” Again, with Phil Collins, you have to accept that “pathetic” and “correct” do not have to be mutually exclusive.

Collins’s problem is that Peter Gabriel is only a musician and songwriter, while Phil Collins is an emblem. You can judge Gabriel’s songs on their merits, but liking or disliking Collins is a statement about so much more than just “One More Night” or “Land of Confusion.” He’s achieved that rarefied level of celebrity in which people use your art as a way to define themselves, a great compliment and a detestable curse.

If we must compare Collins and Gabriel, I’d make a case for Collins being the superior singer. I know this will seem counterintuitive, as Gabriel is regarded as the finest vocalist to come out of prog, the only person associated with that swords-and-unicorns subgenre that can be credibly compared to Otis Redding or Sam Cooke.

But Gabriel could only ever sound like Gabriel. When he was in Genesis, and trotting about the stage with bat wings and oversized flower petals hanging from his head, he could never alter that husky, elderly dragon purr in his voice. Collins isn’t like that. He never needed to wear costumes on stage because he has an ability to sound like a dozen different Phils. It’s what allows him to sing so many different kinds of songs—romantic Phil, soulful Phil, proggy Phil, embittered Phil, balladeer-of the-jungle Phil. He was an actor before he was a singer, and that made him more malleable. He has tried out various inflections, affectations, even accents.

This hasn’t always worked out well. The most infamous track on 1983’s Genesis is “Illegal Alien,” in which Collins’s vocal can only be likened to a grotesque Speedy Gonzales–level caricature of a tequila-swilling Mexican immigrant. (The video doubles down on the abomination.) But as is usually the case with Collins, the ridiculous and the sublime coexist in close quarters on Genesis—the dramatic opening track, “Mama,” is his most majestic performance.

“Mama” was a top-10 song in the U.K., though it was far less successful in the U.S., denting only the lowest reaches of the Hot 100. But it deserves a revival, if only to show that the cinematic sweep of “In the Air Tonight” wasn’t an anomaly for Collins. (“Mama” would’ve fit in perfectly on The Americans.) For the writing of “Mama,” Collins once again made up the lyrics in the moment, singing about a young man’s obsession with a prostitute over a jarring, mechanical rhythm composed by Rutherford, and Banks’s horror-movie synth accents.

Collins’s full emotional palette is on display in “Mama”—he’s tender, he earnestly pleads for love and understanding, and he’s a little goofy. (The song’s signature laugh was supposedly inspired by Melle Mel’s cackle in “The Message,” the recent hit by Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five.) There is also horrifying rage, which explodes when the trademark thunder of Collins’s drums slam in.

When you listen to “Mama,” you can understand how Collins unites Ryan Murphy, Patrick Bateman, Lorde, and Action Bronson. “Mama” offers brainy prog, and pure pop, and big beats, and discomfiting terror, and comforting ’80s cheese. It’s all of those things, and never just one of those things.

Phil Collins requires you to hold many seemingly opposing thoughts in your head at all times. He’s historically underrated as a musician and singer, though lately he might also be a little overrated, too. No Jacket Required and Invisible Touch sound dated, and but they’re also two of the best and most lasting pop albums of the ’80s. I suspect he’s both a nice guy and a bit of a bastard—insecure and humble as well as conceited and megalomaniacal. He’s the Cartesian pop star, eternally resisting absolutism.

Take a look at Phil Collins now. There’s just an empty space, waiting to be filled.

Steven Hyden is the author of two books, including Twilight of the Gods: A Journey to the End of Classic Rock, out now from Dey Street Books. His writing has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, The Washington Post, Billboard, Pitchfork, Rolling Stone, Grantland, The A.V. Club, Slate, and Salon. He is currently the cultural critic at UPROXX and the host of the Celebration Rock podcast.