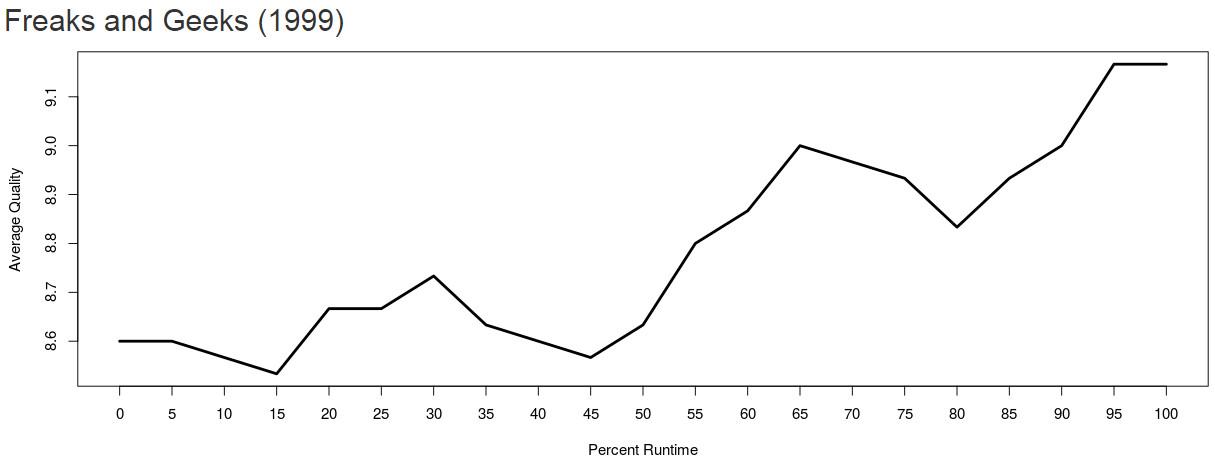

Earlier this month, A&E aired an hour-long documentary about Freaks and Geeks, the beloved high-school dramedy that launched several slacker/outcast-comedy careers. As the Cultureshock retrospective explains, the uncompromising picture of adolescent life that made the series special also made it more difficult for Freaks to connect with contemporary audiences (and some network executives). As a result, the series spanned only a single season, with its 18 episodes airing irregularly from 1999–2000.

Yet even over those 18 episodes, Freaks and Geeks evolved. “We weren’t sure what it was in the beginning,” executive producer Judd Apatow said in the documentary. “We were figuring it out as we went. And if you watch the episodes, you can feel us finding it.” The series’ seven strongest episodes, according to IMDb users, all came in the second half of the season, and the finale, “Discos and Dragons,” is the highest rated of all. Freaks’ cancellation came at its creative apex, but the documentary’s closing comments put a positive spin on the show’s untimely end: At least it didn’t linger long enough for its quality to be tarnished. As series costar Seth Rogen said, “Shows often get terrible.”

We’ll never know whether Freaks and Geeks could have kept its quality from dipping amid (and beyond) the acid trips and pregnancies planned for its second season. But we can examine whether the growing pains that Apatow described—and the hypothetical decline that Rogen alluded to—are typical of TV shows on the whole. In sports, “aging curves” can illuminate the typical trajectory that an athlete’s performance follows: improvement to a point, then a plateau, and eventually erosion as time takes its toll. TV shows aren’t necessarily subject to the same forces that govern human maturation and mortality, but there is a pattern to their progression and a point at which they typically peak.

On Monday, The Ringer released its ranking of the 100 best TV episodes since 2000. Every entry on the list represents a creative high point, which made us wonder when and why the high points of most series come and what happens both before and after they arrive. To trace the life cycle of the average TV series, we gathered episode-by-episode IMDb user ratings (which are expressed on a 1-10 scale) for the nearly 1,500 shows with at least 5,000 votes. Granted, the quality of a creative endeavor like a TV episode can’t be quantified as easily as an athlete’s exploits: As writer/producer Alec Berg (Seinfeld, Curb Your Enthusiasm, Silicon Valley, Barry) says via direct message, “The very best episodes of an unbelievably innovative show may meet with a thunderous lack of response from an audience. They don’t get it, at all.” In some cases, Berg adds, the audience rating may be less a direct reflection of a show’s merit and more a measurement of when viewers “start to ‘get’ the show and when … they tire of it.”

Given a sufficient sample and enough time for audiences to reappraise what they’ve seen, though, it seems reasonable to suggest that there would be some relationship between the quality of an episode and viewers’ collective evaluations of its quality. If a large enough group didn’t “get” it, it may not have been effective at conveying the message that its creator intended to impart. In the absence of a purely objective assessment of an episode’s worth, the wisdom-of-crowds approach can be a telling tool—and, at times, the factor that determines whether a series stays on the air. As it turns out, the conclusions we can draw from the stats align in some ways with what casual TV viewers might expect, as well as what TV creators have told us about the process of producing long-running shows.

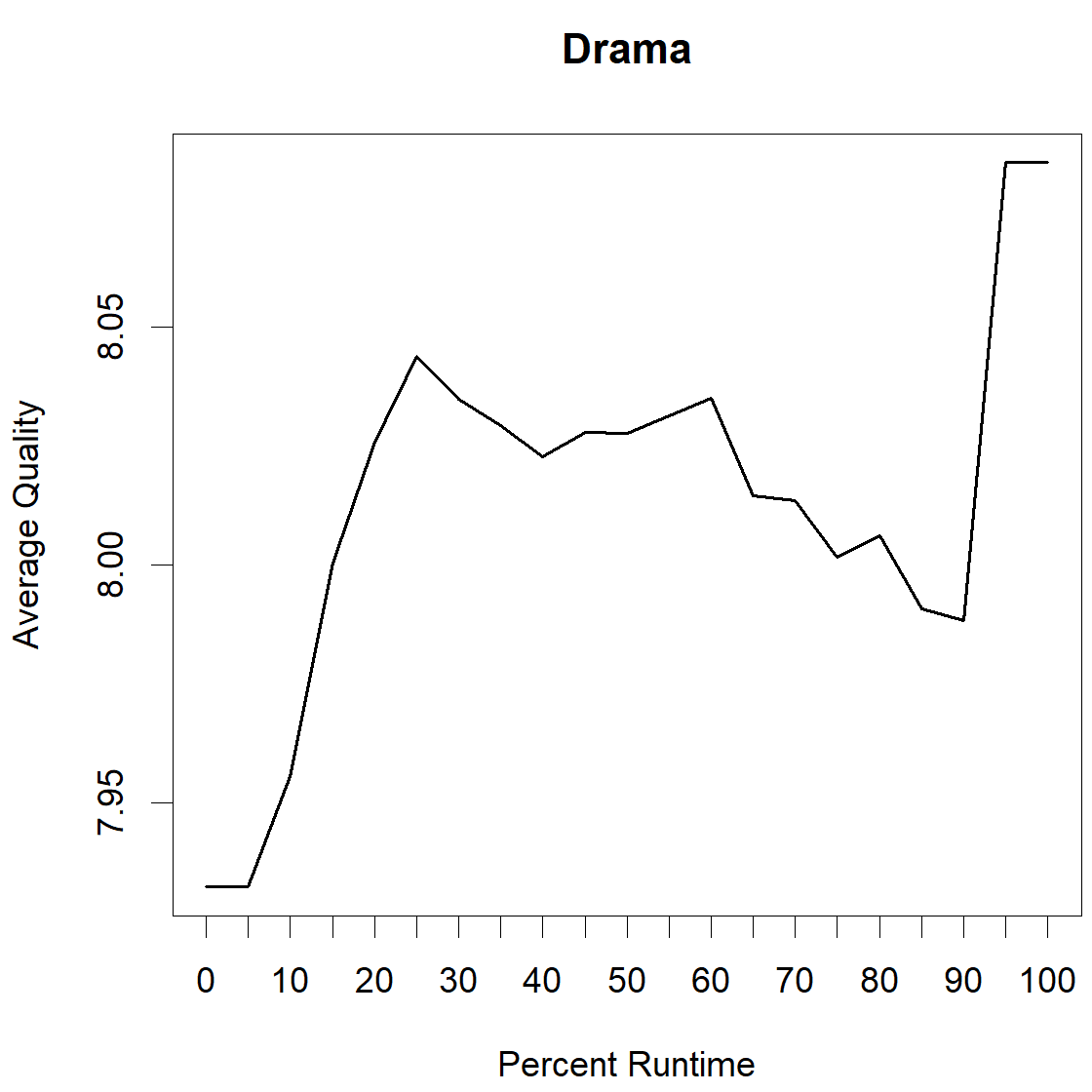

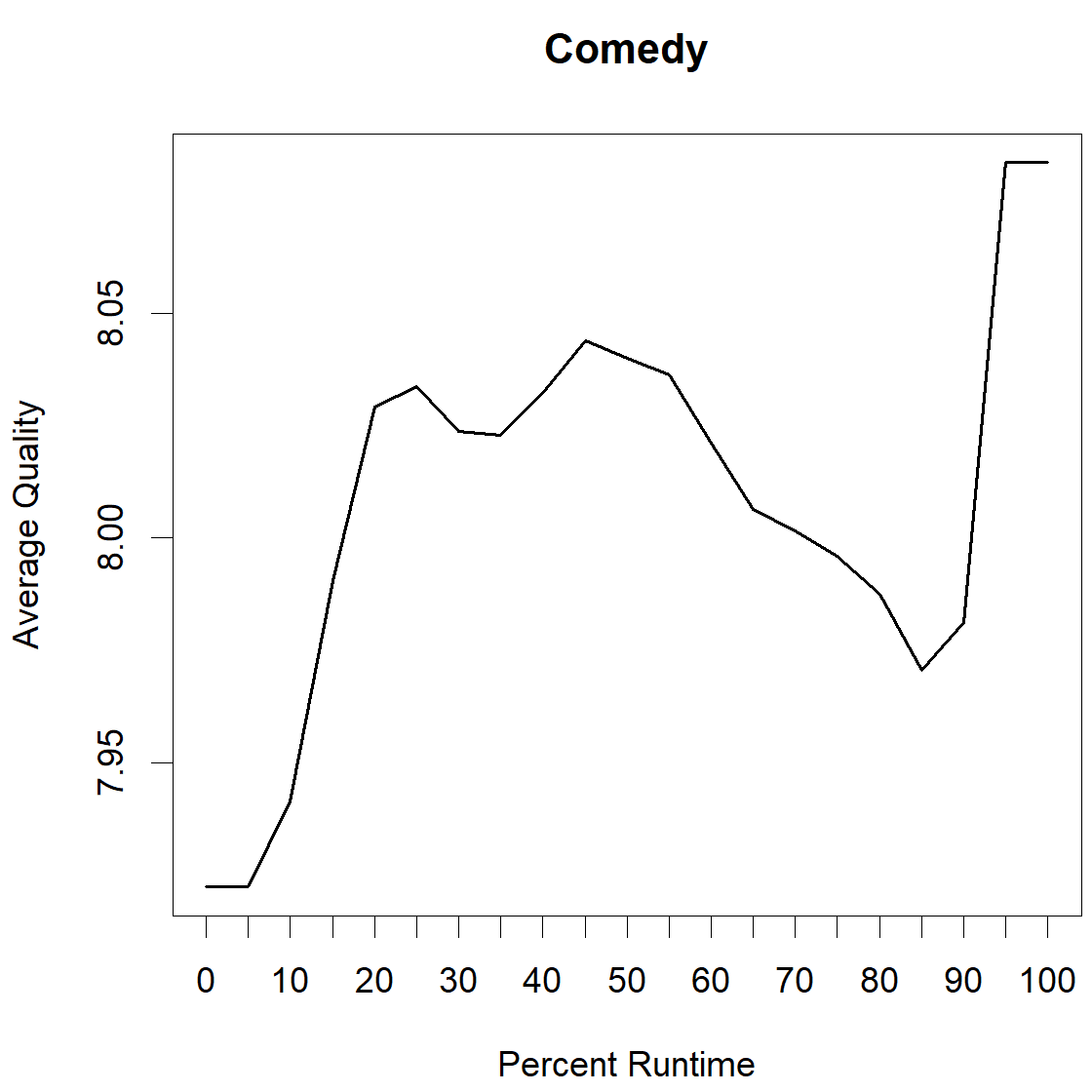

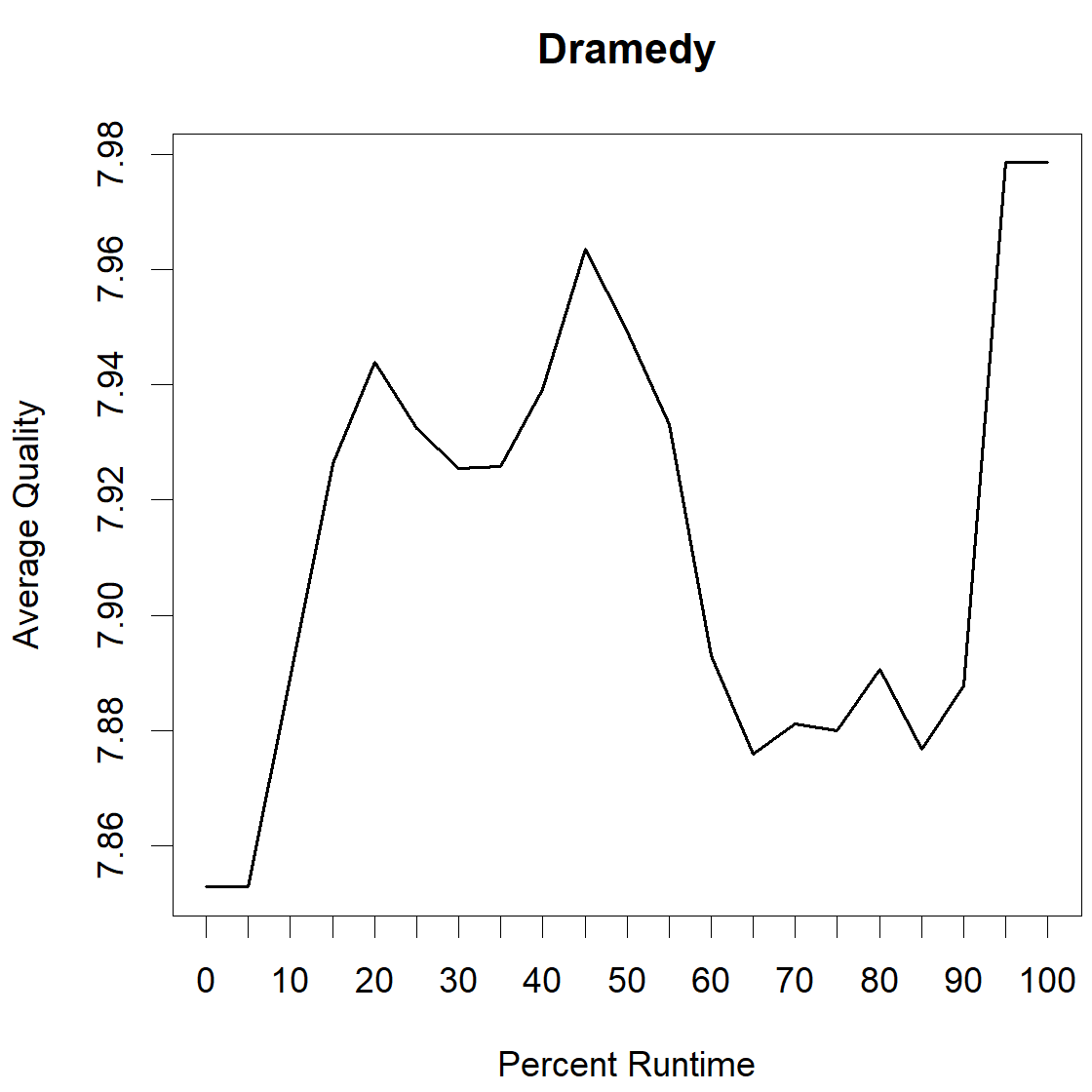

To generate our TV aging curves, we filtered out documentaries, any show in the sample with only one season (sorry, Freaks and Geeks), and all active shows with fewer than five seasons, so as not to skew the trajectories by including series that are still in the early stages of their life cycles. In order to compare shows of varying lengths on the same scale, we made our x-axis “percent runtime,” or the percentage of the way toward the series’ conclusion. In other words, the 50 percent mark, or halfway point, would represent the end of the second season for a series that ran four seasons of equal length, or the end of the fourth season for a series that ran eight seasons of equal length. The average drama in our sample ran 4.3 seasons and 68 episodes, while the average comedy ran 5.6 seasons and 108 episodes. The average dramedy—which IMDb classified as belonging to both the comedy and drama classifications—ran 4.4 seasons and 77 episodes.

The very best episodes of an unbelievably innovative show may meet with a thunderous lack of response from an audience. They don’t get it, at all.Writer/producer Alec Berg

The graph below shows the aging curve for dramas. The higher the line, the higher the audience-perceived quality at that point in the typical series’ run. The average quality for all shows combined is close to the top end of the 1–10 range because the sample is restricted to series that were popular enough to draw the minimum number of votes required to qualify.

All three of the curves exhibit somewhat similar structures, so we’ll share all of them before breaking down what we’re seeing. Here are the comedies:

And last, the dramedies:

The GIF below alternates between those three images for comparison’s sake.

Because these charts are blending the trajectories of hundreds of shows, each of which takes its own path to completion, the magnitude of the longitudinal changes seems small. But there’s a clear shape to all of the graphs: an initial incline—the phase of which Apatow said, “You can feel us finding it”—leading up to a peak, a plateau, a decline, and then a rebound right at the end, corresponding to the series finale. There are some slight genre-dependent differences: Comedies and dramedies tend to peak 45 percent of the way through their runs, while dramas peak 25 percent of the way through their runs. The average comedy remains within .02 points of its peak for 30 percent of its run, while dramas and dramedies stay in that sweet spot for 20 percent and 10 percent of their runs, respectively. In general, dramas are the most resistant to steep declines, maybe because the sheer need to know what happens next keeps audiences placated even if the plotting and writing aren’t quite as adept as they once were.

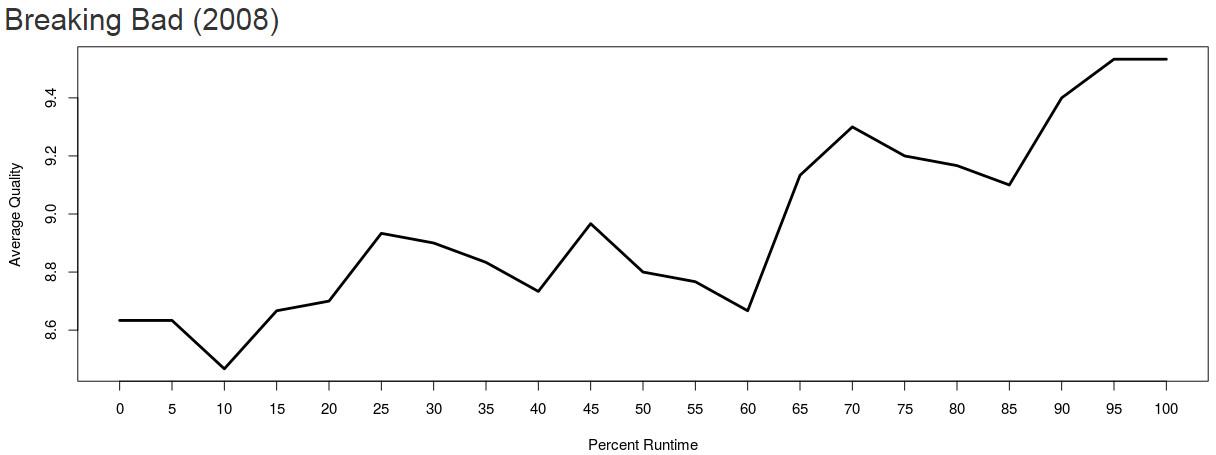

Naturally, individual shows deviate dramatically from the overall trends. Using the interactive tool here, you can view the quality trajectory of any series with at least 5,000 user ratings on IMDb. Just click on that link and select any show title from the alphabetical drop-down menu to display its complete plot. You can also browse statistical data on comedies, dramedies, and dramas and sort them by any of three criteria: their similarity to the typical trajectory for their genre (the lower the number, the more similar the show); the point in their runs at which they hit their pre-finale peaks; and the slope of the most direct line through the first 85 percent of their runs (to avoid finales). A high and positive slope indicates a show that the audience decided gradually got better, like Breaking Bad.

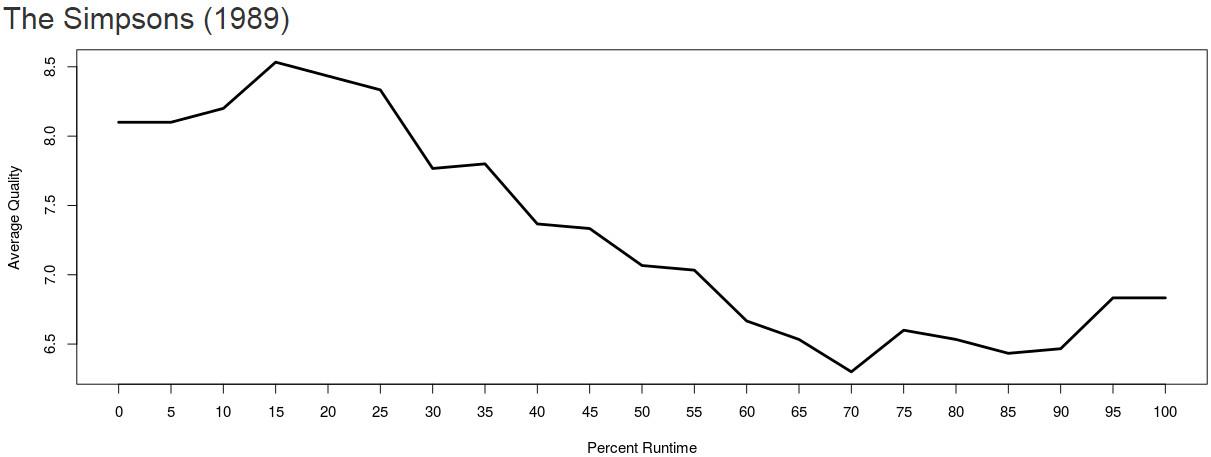

A low and negative slope indicates a show that the audience thought gradually got worse, like The Simpsons.

The trends we found passed the sniff test for TV creators when we shared our research with them via email. In particular, our sources all say they’ve encountered the stumbling blocks that often lead to a delay between a TV show’s debut and the point when it becomes its best self.

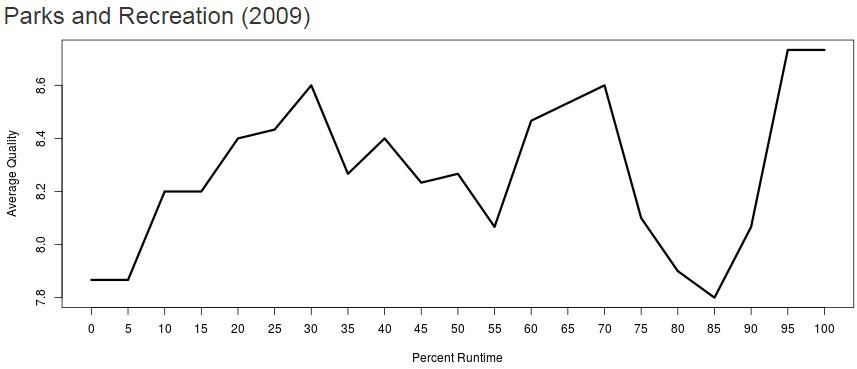

“Because a lot of TV writing is trial and error, I’ve often said, and still believe, that if money and time were no objects, every comedy show would write, shoot, and edit like eight to 10 episodes, study them, and then throw them all away,” says Michael Schur, who wrote for Saturday Night Live and the American version of The Office and cocreated Parks and Recreation, Brooklyn Nine-Nine, and The Good Place. “It just takes a while for writers to learn how to write characters and for actors to learn how to act them.” Veep showrunner and SNL, Seinfeld, and Curb veteran David Mandel describes the same phenomenon of finding a show’s voice as it goes, saying, “Sometimes those early shows are like the rehearsals, only America is watching.”

In Schur’s experience, there’s always a eureka moment when a show’s successful formula becomes clear. At some point in the first season, he says, “There will be a story or a scene or literally a single joke, and when it is pitched and/or read at a table read and/or shot, everyone will kind of go, ‘Ohhhhhhhkay.’ It’s almost like an audible chime goes off, where you recognize that that joke or scene or moment is ‘correct’ in some way. And then at some point (usually) after that, an entire episode will fall into place, and you will use that as a template for all future episodes.” Schur says that The Office adapter Greg Daniels called that the “ur-Episode”—the one that the writers and showrunners refer back to when they need to remind themselves how their show works.

On The Office, Schur says, the ur-Episode was “Diversity Day” (Season 1, Episode 2). On Parks and Recreation, which famously blossomed in its second season, it was “Rock Show,” the first season’s final episode. “It was fascinating to watch the writers fix the show as you watched it,” Mandel says about watching early Parks and Rec from afar. “Slowly, [Leslie Knope’s] pit receded, the characters changed, people left, and others were brought in. It clicked.”

That early learning curve is partly a product of the need for repetition and practice that underlies almost any skill-based exercise. But it also stems from the ongoing dialogue between producers, critics, and consumers. Before a series reaches screens, its creators have to craft characters and relationships without being able to gauge a large audience’s reaction, a valuable form of feedback that often alters the shape of the show. “Once the show begins to air you start to see what’s working and what isn’t,” says Peter Casey, a writer and producer for The Jeffersons and Cheers who later cocreated Wings and Frasier. “If what you’re doing is working, great; keep going. But sometimes you come to realize that the gold is found in a different direction. If that’s the case you’re silly to stick with your original plan.” Casey and his cocreators originally envisioned Frasier’s relationship with his father as the centerpiece of that sitcom, but after the series debuted, they began to build up the brotherly relationship between Frasier and Niles in response to the audience’s enthusiasm. “The beginning of a series is a fight for survival,” he says. “You’re doing everything you can to keep your head above water.”

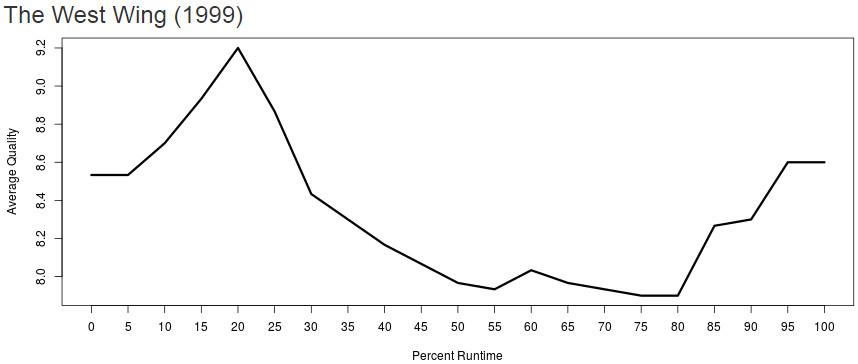

Kevin Falls, who served as a producer or showrunner on The West Wing, Franklin & Bash, Pitch, and other series and recently joined the staff of This Is Us as a co-EP, points out that negotiating network notes and testing is another factor that can complicate a series’ conception of itself in the early going. “Add the burden of story/character exposition in the first few episodes of any drama and suddenly you have a show that’s stuffed and wobbling out of the gate, like when you step into the night after a huge meal at some gastro pub,” he says. “It’s going to take you a couple of blocks to walk it off.”

In those nascent stages, the most important trait that a showrunner can possess is pliability. “You have to bail on things that don’t work, even if you’ve sunk a ton of time into them,” Schur says. “You have to accept and implement the best ideas, no matter whom they come from.” When The Ringer’s list of the top 100 TV episodes since 2000 is sorted by season and, secondarily, episode number, the median entry is Season 2, Episode 8. That timing falls in line with what the stats pinpoint as the typical peak period. “The reason that most shows’ best seasons are nos. 2 and 3 is because you’ve had enough time to learn about the characters and the audience has had enough time to get to know them, but you haven’t exhausted what’s interesting about them, and there are still new dynamics and relationships that can unfold in a surprising way,” Schur says.

If money and time were no objects, every comedy show would write, shoot, and edit like eight to 10 episodes, study them, and then throw them all away,Michael Schur, cocreator of Parks and Recreation, Brooklyn Nine-Nine, and The Good Place

Naturally, there are always exceptions: The Ringer’s top-100 list includes pilots of three scripted, multi-season series: The O.C., Eastbound & Down, and Pushing Daisies. Kath Lingenfelter, who served as executive story editor on Pushing Daisies and later worked as a supervising producer on House and The Leftovers (two other shows with entries on the list), says that Daisies bucked the trend of needing to build up to the best episodes because its protagonist, Ned (a.k.a. “The Piemaker”), “had lived with [series creator] Bryan Fuller for years,” ever since Fuller conceived the character while working on Dead Like Me. That allowed the series to take a shortcut on what Lingenfelter refers to as the “road that must be traveled and time that must be lived with characters and their world” before they hit their stride. “It was a rare pilot, undeniably,” she says.

Once all of the possible paths that a show can take to its peak are winnowed into one and the series achieves what Falls calls the “elusive harmonic convergence” of writing, acting, and directing that makes it sing, the creator’s task transitions to warding off decline by keeping the character depth and cliffhangers coming. Achieving that goal is much more manageable if the creators have looked long-term and laid groundwork for future developments from the start. “When I’m running a show, on the first day I meet with the writers I share with them the old football adage, ‘Super Bowls are won in August,’” Falls says, adding, “The creator has to have a plan, one that she or he has discussed with fellow producers that plants story flags of where the show wants to go.”

A comforting familiarity is central to TV’s appeal; procedurals depend on it, and some networks, such as old-school CBS, may regard creative ruts as closer to lucrative grooves as long as the ratings are robust. Even so, every series needs a certain amount of novelty to keep people hooked, especially in an era of endless entertainment alternatives. “You’re always at risk of running the ship aground,” Schur says.

Lingenfelter explains that the moment when it finally feels as if things are under control is the right time to shift gears. “Once everyone is comfortable, creator and audience, then you can start bending rules (as with ‘House’s Head’ and ‘International Assassin’),” she says, referring to the House and The Leftovers representatives, respectively, on The Ringer’s list. Constant self-scrutiny and repeated reinvention are the only antidotes to stagnation. “I think it’s hard to know when it’s happening,” Mandel says. “I have seen it happen to shows I liked to watch, and it sneaks up on you. All of a sudden, you the viewer [are] bored.” Mandel credits Curb’s and Veep’s longevity to their respective creators’ commitments to mixing things up. “With Veep, Armando [Iannucci] set a path early of practically reinventing the show every year, when most people might have let it be,” he says, adding, “When I was doing Curb with Larry David, each season would have a new overarching story that kept the show fresh.” New cast members can also supply a needed jolt, which Casey recalls Kirstie Alley doing on Cheers when she replaced Shelley Long in Season 6.

Each of the genre aging curves features multiple high points prior to its decline, perhaps reflecting times when the creators sensed sameness setting in and made tweaks that touched off creative renaissances. “I like breaking the form every few episodes so the viewer doesn’t get too comfortable and complacent in how they watch a show,” Falls says. “Audiences like to be challenged sometimes.” But pulling the narrative rug out from under the audience’s figurative feet works only so many times. “Making change for the sake of change can get stale, too,” Falls says. “Those shocking twists for the sake of twists can lose their impact over time and actually become predictable.” Veep’s Season 5, Episode 9 entry on our top-100 list, “Kissing Your Sister,” is a perfect example of a happy medium between straying too far from a formula and sticking too tightly to one, employing a documentary format that demands the viewer’s attention without breaking the contract that a series implicitly signs with its loyal fans.

If what you’re doing is working, great; keep going. But sometimes you come to realize that the gold is found in a different direction. If that’s the case you’re silly to stick with your original plan.Peter Casey, cocreator of Wings and Frasier

Eventually, the grind gets to creators, especially those on networks that still rely on longer seasons that leave less time to polish each episode. “The blast furnace that is production needs to be fed daily,” Falls says. “That next outline or script or cut is always nipping at your heels. I’ve seen so many showrunners buckle under the pressure.” Actors and creators who can withstand that pressure often attract suitors, which can come at a cost to the series they’re already attached to. “TV shows get raided,” Falls says. “After a season or two, writers on successful shows get plucked with overall deals or a pilot, not unlike a championship team losing players and front-office personnel. Supporting actors that gained traction on a drama get a series commitment on another show and now you can’t use them anymore. New stars get movies and realize they’ve committed themselves to a TV show for seven series and now wish they hadn’t, and on some occasions their performance suffers.” Witness the swoon that The West Wing went into as creator Aaron Sorkin dealt with stress and budget constraints and finally left the series along with colleagues including Falls.

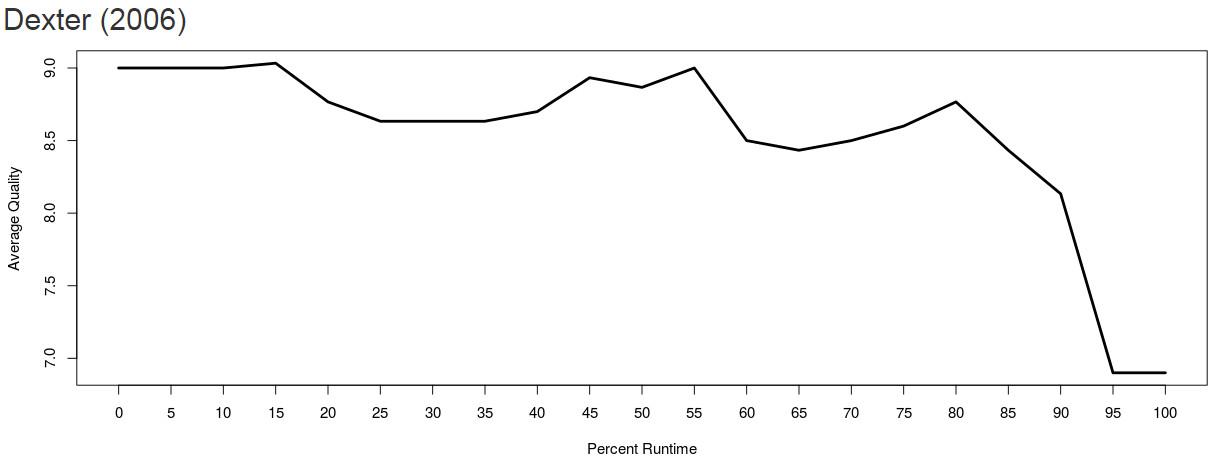

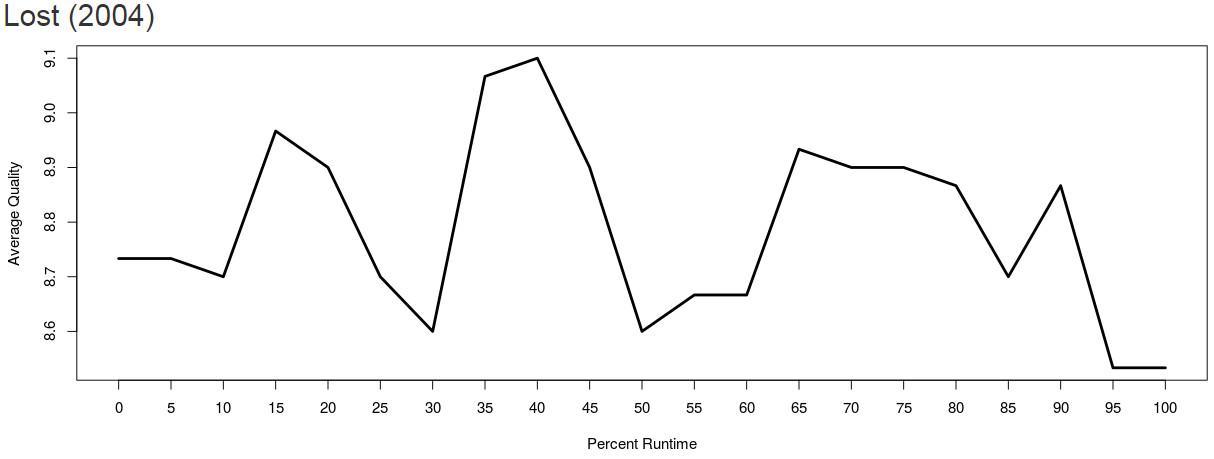

The series finale often offers a chance for a show’s viewer rating to return to heights unseen for several seasons or soar to an unprecedented point. Not in every case, of course; if a series fumbles the finish, as did Dexter and the up-and-down Lost, its rating can reach a nadir at the end, tarnishing the totality of the show.

Barring a glaring failure to pay off plotlines that were years in the making, though, finales tend to be crowd-pleasers. After struggling to sustain rivalries and romantic triangles season after season, showrunners can finally use their remaining material in one big burst and unite (or kill) characters that viewers have long wanted to get together or get their comeuppance. The Ringer’s top-100 list includes the finales of four shows: Six Feet Under, Parks and Rec, Battlestar Galactica, and The Jinx.

No show can fight the forces of entropy forever. Inevitably, the story well starts to dry up, the creators and stars begin to get antsy, or the audience’s appetite for the same faces fades. Some shows get to go out on their own terms. Others, as Rogen said, get terrible. One way or another, they pass into TV antiquity.

Then, with any luck, new projects approach and the battle against boredom begins again. Of course, creators learn from every notch on their IMDb bedposts; Casey says that the struggle to service Wings’ many series regulars taught him and his partners to keep Frasier’s core cast small. Schur notes that experience teaches showrunners “what to sweat and not sweat,” adding that accruing a stable of capable crew members—from costume and prop people to art directors and set builders—subtracts some uncertainty, saves time, and eases the strain on the higher-ups. And Falls observes that working with partners such as Sorkin and Dan Fogelman has allowed him to internalize tips and tricks from other proven producers.

But those advantages lighten the load only on the margins. “The basic process is always going to be hard and nerve-wracking,” Schur says. Mandel expresses a similar sentiment: “Every show is sadly different. It never gets easier.” From the audience’s perspective, though, that difference isn’t sad. It’s the reason we’re always willing to tune in again. When the next pilot appears, it may be rough around the edges. But history tells us that another peak should be coming soon.