Da Story of Da Bears: How an ‘SNL’ Sketch Defined Sports Fandom

Chicago’s mustached, Mike Ditka–loving Super Fans became some of the most enduring characters in the history of ‘Saturday Night Live.’ And it all started at Wrigley Field.When Robert Smigel first visited Wrigley Field, he immediately noticed the look. Heavyset fans sporting walrus mustaches and big sunglasses were everywhere. It was 1983, three years after The Blues Brothers hit theaters and a season into Mike Ditka’s tenure as head coach of the Bears. In addition to Old Style, the crowd seemed to be under the influence of both the movie and the man.

“There was just a swagger among these very virile-looking men,” Smigel said. “All sports fans kind of have it. The arrogance of, ‘We kicked your ass!’ No, you didn’t. You’re a fat guy sitting in the third row. You can barely make it to the bathroom with all the beers you’ve drunk. You didn’t do anything.”

Yet there was something about these hirsute galoots that was endearingly hilarious. Maybe it was the unwavering, borderline delusional faith they had in their teams. Or maybe it was their cartoonishly large aviator shades. Whatever it was, Smigel banked the memory of those lovable oafs. Soon after he moved to Chicago to begin his comedy career, the city’s sports franchises started to ascend. In 1983, the White Sox made the postseason for the first time since 1959. In June 1984, the Bulls drafted Michael Jordan. That fall, the Cubs ended a 39-year postseason drought. Then the Ditka-led ’85 Bears tore through the NFL like it was a soggy Italian beef.

Success, Smigel said, “just allowed for the swagger to grow.” Around that time, he considered the possibility of dropping hardcore Chicago fans into a sketch. But initially, all he had was a two-word phrase: “Da Bears!”

“That arrogant way of saying it,” Smigel said before turning on his still-properly-nasal Chicago accent. “It’s in the bag. They’re gonna win. Read ’em and weep.” He told only one person about the idea: an improv classmate who grew up in nearby Naperville. His name was Bob Odenkirk. “I happened to find him to be the funniest person in Chicago,” Smigel said. Odenkirk gave his friend a tip: emphasize the final two letters in the word bears. “The little hiss at the end,” Smigel said. “You have to be from Chicago to know that.”

What Smigel lacked was somewhere to put the characters living in his head. He eventually joined the writing staff of Saturday Night Live. Soon Odenkirk also came on board. Then, in the spring and summer of 1988, the Writers Guild of America went on strike. With time on their hands, Smigel, Odenkirk, and SNL colleague Conan O’Brien starred in their own stage revue. Running from late June to early August at Victory Gardens Studio Theater in Lincoln Park, Happy Happy Good Show inadvertently turned into a comedy testing ground. The production featured versions of In the Year 2000, later a signature of O’Brien’s late-night program, and a bawdy nude beach bit, which ended up on SNL. Also making their debut: a group of buddies sitting in lawn chairs and drinking beer. Played by Smigel, Odenkirk, and Dave Reynolds, who went on to cowrite Finding Nemo, the pals passed the time by riffing about their favorite football team.

“Over and over, it was these labored connections they would make, in the most verbose way possible,” Smigel said, “in order to get back to reassuring each other that the Bears were gonna win the Super Bowl.” At one point O’Brien even popped up as one of their sons. “He sort of ended up as a sight gag because he was really skinny,” Smigel said.

The sketch killed. But when Happy Happy Good Show made a brief stop in Los Angeles, Smigel cut it. He was sure that no one outside of Illinois would understand what was so funny about a bunch of irrational Chicago fans soothing each other by claiming the Bears were going to win their next game 82-3.

Little did Smigel know that he’d created an archetype. His now 30-year-old characters remain the only-slightly-exaggerated embodiment of America’s obsession with sports. Every depiction of a comically devoted fan over the past three decades owes a debt to Smigel’s portly, mustached diehards.

Back in the late 1980s and early 1990s, however, Smigel admittedly didn’t see their potential. “I’d never thought of it as something that could work on national television,” he said, “because it just felt so regional.”

Then in January 1991, actor Joe Mantegna came to New York City to host Saturday Night Live. The Chicago native’s presence led Odenkirk to press Smigel to try pitching a sketch about the city’s special brand of fandom. “Bob came to me,” Smigel remembered, “and said, ‘We should try the characters. We should try those guys.’ And it’s like, ‘What?’”

Sure enough, Mantegna liked the concept. But the sketch still needed a setting. For that, the writers turned to a Chicago institution. In 1985, The Sports Writers on TV premiered on UHF station WFLD. The weekly roundtable, an adaptation of a long-running radio show, centered on three scribes who were as deliciously crusty as a Pequod’s pizza—the late trio of Bill Gleason, Ben Bentley, and Bill Jauss—and upstart Rick Telander, who today is almost 70.

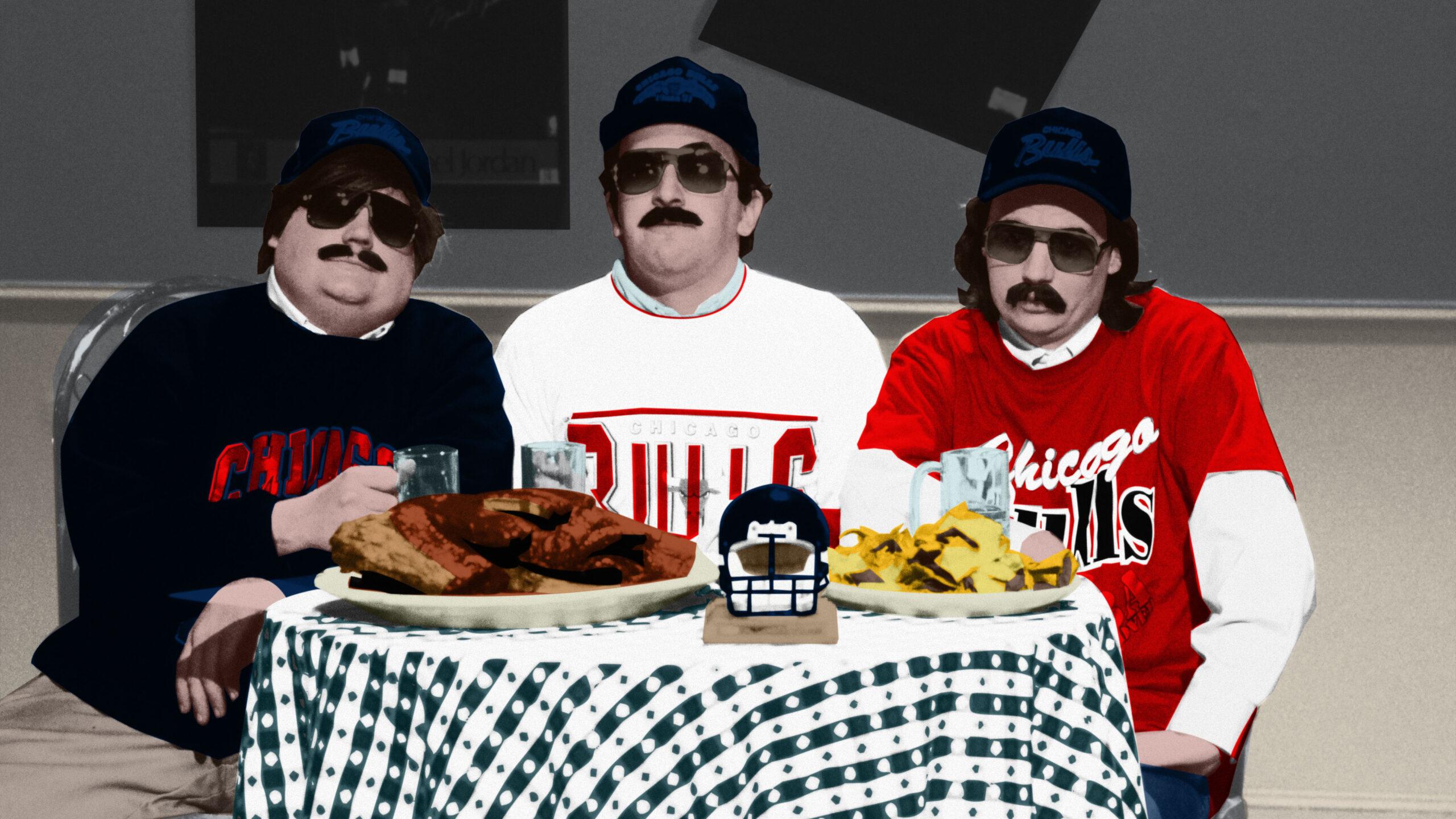

Odenkirk thought it would be funny to drop a handful of nonexpert goons into that environment. And thus “Bill Swerski’s Super Fans”—Chuck Swirsky is a longtime Chicago sportscaster—was born. Mantegna plays the title character, who hosts his own show at Ditka’s Restaurant. He’s surrounded by his buddies, including Todd O’Conner (Chris Farley), Pat Arnold (Mike Myers), and Carl Wollarski (Smigel).

“The key was that table,” said John Roach, creator of The Sports Writers on TV. “Men gathered at a table talking about the shit in an unscripted way that lets you eavesdrop on it. That was the beauty of The Sports Writers. And the thing that I loved about the ‘Super Fans’ sketch is that they had those guys around that table.”

The other thing that Roach loved: the accents. “Gleason had an incredibly thick Chicago accent. I can hear his voice in their take on the Chicago accent. Very nasal.” In fact, Smigel said that he was only in the sketch because SNL head writer Jim Downey, himself a Joliet, Illinois, native, thought that he had an authentic-sounding accent. Smigel was shocked. He’d written the part for Phil Hartman.

“I loved it,” Smigel said. “I got to wear sunglasses so I didn’t have to memorize my lines. I mean nobody has to memorize their lines on SNL, but it’s really easy to read the cue cards when you’re wearing sunglasses. And I could also eat during the sketch. So I had something to do with my hands and not be nervous. It just relaxed me that I could actually eat a beef rib while I’m on national television.”

The Super Fans were always eating. And in between stuffing their faces with red meat, bashing New York, and predicting the score of the next afternoon’s Bears-Giants playoff game—“Bears. 79-zip,” O’Conner says—they worshiped their idol. When Swerski asks who would win a golf match, Ditka or God, the group’s unanimous answer is “Ditka!” To many in the Midwest’s biggest city, the coach was Paul Bunyan who instead of an ax wielded a flipped bird.

“You cannot underestimate the effect of the ’85 Bears and Ditka on the Chicago psyche,” Roach said. “He still haunts Chicago.” The coach, who was also a Hall of Fame tight end for the Bears, achieved folk hero status at least partially by being objectively ridiculous. He screamed. He cursed. He once took a wad of gum out of his mouth and stuck it on a reporter’s camera lens. He even allegedly broke his right hand punching a hard surface—I’ve seen it reported as a wall, a file cabinet, and an equipment trunk—and then told his team to ‘Win one for Lefty.’”

There was just a swagger among these very virile-looking men. All sports fans kind of have it. The arrogance of, ‘We kicked your ass!’ No, you didn’t. You’re a fat guy sitting in the third row. You can barely make it to the bathroom with all the beers you’ve drunk. You didn’t do anything.Robert Smigel

Telander wrote a book with Ditka. If there’s one thing that the journalist learned, it’s that Ditka follows no one’s schedule but his own. If he’s somewhere in public and all of a sudden feels like leaving, he will. “He’ll just stand up, knock his chair over, and walk out,” said Telander, a veteran Sun-Times columnist, former Sports Illustrated writer, and author of Heaven Is a Playground.

The Super Fans, like the guys that inspired them, didn’t just love Ditka. They wanted to be Ditka. “To me at least, they just made every character Mike Ditka, OK?” said Roach, who had Ditka on The Sports Writers on TV on a few occasions. “So that was their quantum leap comedically.”

The sketch drew big laughs. But Smigel figured it was a one-off deal. “We thought it was over,” he said. Smigel made a mistake that the Super Fans certainly wouldn’t have tolerated: He underestimated the power of Da Bears.

Back then, Chicago radio personality Jonathon Brandmeier was always looking for material for his popular show on WLUP, “The Loop.” When “Johnny B” saw “Bill Swerski’s Super Fans,” he knew it would go over big with his audience. “I’m a freak for audio,” Brandmeier said. “I love grabbing it, playing it, editing it. I heard ‘Da Bears! Da Bears!’ and I highlighted it and kept playing it.”

Smigel started hearing the same refrain from friends in Chicago: “Brandmeier’s playing your sketch!” And “Da Bears!” was becoming ubiquitous. “That wasn’t a phrase,” Brandmeier said. “It was just two words. But damn good ones.” In the original script, Smigel said it was written “The Bears.” The Chicagoization of it was organic. “It just came out that way,” Smigel said. “We didn’t imagine it being a newspaper headline sometime.”

On May 18, 1991, actor George Wendt hosted Saturday Night Live. The Cheers star, a Second City alum from the South Side, was a fan of the first “Super Fans” sketch. He was the perfect person to play Bob Swerski. In the second incarnation of “Super Fans,” Wendt fills in for his “brudder” Bill, “who’s still recovering from that dreadful heart attack.” The episode aired in the middle of the Bulls’ first NBA championship run. In the “Super Fans” sketch, a Bulls tank top–clad O’Conner predicts that “Da Bulls” would beat the Pistons in Game 1 of the Eastern Conference finals 402-zip. “But,” he adds, “Michael Jordan will be held to under 200 points.”

As was usually the case, every line Farley delivered was hysterical. “He had that physicality, that swag, that just put it over,” Wendt said. “He could say anything, and then with his body language, it would just be hilarious. ‘How are ya, Bob?’ It’s not a joke at all unless it’s Farley.”

Roach, whose brother played high school football with Farley in Madison, Wisconsin, still laughs at the thought of his friend wearing aviators and a fake mustache. “I personally feel that he took that sketch and made it unforgettable,” said Roach. “If you hadn’t had Farley in that sketch, I don’t know if we’d be talking about it right now.”

After Wendt joined in, the Super Fans were officially recurring characters. That summer at a Comic Relief event in Chicago, the group appeared in a sketch with Michael Jordan. “That’s what led to him feeling comfortable hosting Saturday Night Live,” Smigel said. Fresh off his first title, MJ hosted the SNL season premiere. In one memorable sketch, he plays Sweet River Baines, the first black Harlem Globetrotter.

“There’s a moment where a guy takes a two-handed set shot and Michael blocks it with both hands, just swats it really hard back at the guy,” Smigel said. “That’s me.” Part of that segment was prerecorded. While filming in a gym, Smigel got a close look at Jordan’s near-pathological competitiveness.

“There’s just actors there playing all these roles,” Smigel said. “And so during a break he’s just checking out the guys, watching. And he’s disgusted. ‘Look at these guys. Just a bunch of weekend hacks.’ I’m like, ‘Yeah, they’re not supposed to be that good. They’re white guys from the ’40s.’”

Jordan also pops up on “Bill Swerski’s Super Fans,” during which O’Conner survives a 13th heart attack. By then, the sketch was hard to kill.

In late December, the Bears invited Farley, Wendt, and Smigel to Soldier Field for Chicago’s wild-card matchup against the Cowboys. The Super Fans fired up the crowd and during the game stood on the sideline in costume. At halftime, they were inexplicably encouraged to invade a youth punt, pass, and kick competition.

“This was a fuckin’ playoff game!” Smigel reminded me. Farley went first, and while attempting to kick a field goal, purposely fell flat on his face. “That’s a magic piece of film,” Wendt said.

The crowd exploded. “And then I have to follow him,” Smigel said. Wendt quickly suggested that Smigel take a bite of hot dog, sip a beer, and try to drill the kick. Somehow, Smigel made the field goal. “It was 20 yards on a tee,” he said. “It wasn’t impressive.” To close the impromptu halftime show, Farley snapped the ball to Smigel, who pitched back to Wendt, who ran into the end zone.

“Then I head-butted Farley,” Wendt said. “But we didn’t have helmets on. That was a poor choice on my part.”

For Smigel, playing a Super Fan became a fun side job. He and Wendt performed on a stage in Grant Park at several Bulls championship celebrations. About an hour before one such event, Wendt recalled Smigel visiting him in his hotel room. “I’m brushing my teeth in the bathroom and Robert’s in there teaching me this song we’re gonna sing for 300,000 people,” Wendt said. “And not only that, he’s on the phone as well with the guitar player who’s gonna accompany us.”

In 1993, at the inaugural ESPY Awards, the producers parked Smigel and Wendt in a corner of the set. The Super Fans served as the ceremony’s Greek Chorus. From his spot on the stage, Smigel was lucky enough to watch an ailing Jim Valvano accept the Arthur Ashe Courage Award and give his iconic farewell address.

“I can see this fucking monitor starting to flash 30 seconds,” Smigel said. “And I can’t believe it. I couldn’t enjoy the speech. I’m just so tense. I’m just thinking, ‘I can’t believe they’re flashing Valvano to wrap it up. He’s dying. It’s amazing that he’s standing.’” By that point, the sight of the blinking screen made Smigel too uncomfortable to listen to what Valvano was saying. Valvano, however, reacted to the warning deftly, saying, “I got tumors all over my body. I’m worried about some guy in the back going, ‘30 seconds’?”

“I laughed, but had this enormous wash of relief over me,” Smigel said. “Because it was so upsetting. This guy’s courageous enough to come out here. Some people thought he wouldn’t be able to show up. And he’s pouring his heart out. And you’re just suffering inside watching this with disbelief. And then he handles it so effortlessly and takes all the tension away.”

Not very long after the ESPYs, to which the Super Fans would return later in the decade, Smigel left his post at Late Night With Conan O’Brien to collaborate with Odenkirk on a script based on the characters. The movie was supposed to satirize the rapidly corporatizing sports world. The writers envisioned Martin Short as the Napoleonic, money-grubbing Bears owner who wanted to convert Soldier Field—this was prior to its transformation into a glass-encrusted spaceship—into a playground solely for the super rich. Also, the Super Fans watched an All-Ditka channel.

“Bob and I had a 150-page first draft and this executive insisted on seeing it,” Smigel said, so they showed him. “And then he never spoke to us again.” Farley, who by the mid-1990s had become a movie star, also dropped out of the potential film. “By the time he got this script, Tommy Boy was coming out and it was a hit,” Smigel said. Farley’s management team, Smigel added, essentially said, “Wait, you’re gonna be in an ensemble movie? Do a Farley movie!” (During that stretch, Farley also reportedly turned down roles in Kingpin and The Cable Guy.)

He had that physicality, that swag, that just put it over. He could say anything, and then with his body language, it would just be hilarious. ‘How are ya, Bob?’ It’s not a joke at all unless it’s Farley.George Wendt

Alas, the Super Fans movie never got made. Not even one of Todd O’Conner’s vigorous chest poundings could resuscitate the idea. Farley’s death in 1997 ensured that. “When he passed, the project didn’t make sense anymore,” Wendt said. “It’s sad.”

Even without Farley, the Super Fans lived on. Over the past three decades, they’ve starred in more SNL sketches, ESPN segments, and commercials. When Wendt was recovering from double bypass surgery earlier this decade, he asked Smigel to write him a few jokes to post on Facebook. Wendt recalled one going like this: “Doctors have found a piece of Polish sausage lodged in my heart. The medical term for it is Coronary Kielbasis.”

Smigel marvels at the characters’ longevity. At the Mike Ditka roast in 2001, he sat next to Jim McMahon when the guest of honor lost his balance and was pushed off of the stage. The former Bears quarterback responded to his old coach tumbling over by yelling, “Down goes Frazier!”

It was a surreal Chicago moment, one of many Smigel has experienced since his first game at Wrigley back in the early ’80s. That afternoon, when he heard people in the bleachers shouting, “Left field sucks!” and “Right field sucks” at each other, and watched home run balls being thrown back onto the field, he was smitten. “In Chicago, the best seats in the house are the shitty seats,” he said. It’s a lesson that served him well when he created the Super Fans. The irrationally positive, thick-accented men squeezed into Bears jerseys were funny enough to transcend provincialism. After all, every city has a version of those guys.

And while a certain team fired a certain coach 25 years ago, he still looms large over Chicago. In May 2010, at a Just for Laughs charity event, Smigel and Co. staged two readings of the shelved Super Fans movie script. Right before the second show was about to start, a terrified-looking producer approached Smigel and told him that Ditka was gone. “I was like, ‘You just let him leave?’ And we didn’t tell the audience because we thought, ‘This is just gonna ruin their night.’” Former Bears lineman Keith Van Horne filled in admirably, but the crowd still booed.

When Smigel later talked to Ditka, he apologized. The coach didn’t leave because he was angry or petulant. “Bob, I was tired!” Smigel recalled him saying. “I just couldn’t. It was late.” Turns out even Ditka needs sleep.