Astral Weeks turns 50 this month. What a record. Lester Bangs, in perhaps the greatest piece of rock criticism ever written, poetically referred to the 1968 Van Morrison album as a “beacon, a light on the far shores of the murk.” Greil Marcus, less poetically, called it “a profoundly intellectual album,” and meant it as a compliment. Both would agree that Astral Weeks is one of the best 47-minute pieces of music ever created. A landmark in the fusion of rock and jazz. A masterpiece.

But you’ve probably heard people talk about how great Astral Weeks is more than the album itself. Van Morrison’s next record, 1970’s Moondance, is far more popular; if you were sexually active in the late 20th century, Van Morrison likely howled “I wanna rock your Gypsy soul!” at least once during an intimate moment. Given the album’s elevated position in the rock canon, it can be difficult to find your own place in Astral Weeks, to discern it with a personal filter rather than via the plaudits of celebrated rock critics. Can anyone in 2018 queue up “Madame George” for the first time and just hear a song, and not every thinkpiece ever written about it? Astral Weeks might very well be Van Morrison’s most essential LP, but it’s a problematic entry point.

Instead, let’s talk about No Guru, No Method, No Teacher.

No Guru, No Method, No Teacher came out in 1986, 18 years after Morrison’s magnum opus, and about two months shy of his 41st birthday. If you only know Van Morrison from Astral Weeks, the juxtaposition might be startling. On the cover of Astral Weeks, Van resembles a wood nymph in the midst of an intense religious experience; on the cover of No Guru, he looks like a no-nonsense English professor at an exclusive East Coast liberal arts college, or a no-nonsense TV detective portrayed by no-nonsense character actor Bill Camp. Let’s just say that by then he had ventured far beyond the slipstream, and well past the viaducts of your dream.

No Guru, No Method, No Teacher is a benchmark of Morrison’s 3.0 period, which commenced in 1977 with the aptly named A Period of Transition. (Van Morrison’s early garage-rock era with the band Them is 1.0, and the vaunted period between Astral Weeks and 1974’s Veedon Fleece is 2.0.) Over the next decade, he retreated from the mainstream and into a mystical haze of jazzy, gauzy, impossibly smooth-sounding, and spiritually minded adult-contemporary records so devoid of grit that they make Sting sound like Straight Outta Compton. When he deigned to give interviews, he loudly complained about the imposition of celebrity and insisted that he never had anything to do with rock ’n’ roll at all. Though, having said that, he also loathed how seemingly all of the era’s defining heartland rockers had ripped him off — Americans like Bob Seger, Tom Petty, and John Mellencamp covered his songs, while singer-songwriters from the English heartland, including Elvis Costello and Graham Parker, also owed him an obvious debt.

But the most egregious of these thieves, in Morrison’s mind, was Bruce Springsteen. “For years people have been saying to me — you know, nudge, nudge — have you heard this guy Springsteen?” Morrison griped to The New Age in 1985, right when Born in the U.S.A. was at its most ubiquitous. “And he’s definitely ripped me off … [and] I feel pissed off now that I know about it.”

What Van couldn’t (or wouldn’t) accept is that the messianic pub rock that he perfected in the early ’70s on albums like 1970’s His Band and the Street Choir and 1972’s Saint Dominic’s Preview was readily available to others because he himself had long since abandoned it. Hell, he had forsaken that music, right when the rest of the world caught up with it.

For as much credit as Bob Dylan and Neil Young get for their anticommercial contrarianism, nobody is more perverse than Van Morrison. Dylan and Young reacted to middle age by, respectively, going Christian and antagonizing David Geffen; Morrison made a half-instrumental record that sounds like a cross between traditional Irish music and Roxy Music’s Avalon, and dedicated it to L. Ron Hubbard. It’s not a shock that consumers opted instead for “Dancing in the Dark.”

Lest it sound like I’m criticizing Van Morrison for any of this, allow me to state for the record that I absolutely adore this era of his career. That Celtic Roxy Music L. Ron Hubbard record, 1983’s Inarticulate Speech of the Heart, is strange and singular and kind of wonderful. What Morrison’s ’80s albums lack in even the faintest edge they make up for in beauty, craft, conviction, and the benefit of his utterly fascinating split personality, in which his unending quest for holy transcendence exists side-by-side with his equally intransigent pettiness over an infinite number of grievances, both real and imagined. In the ’80s and beyond, Van Morrison was no longer the angel of Astral Weeks, wailing toward the heavens in gorgeously pained ecstasy. He was the man who fell to Earth, fighting in vain to get back to paradise and yet stuck, with increasing frustration, earthbound.

The central track on No Guru, No Method, No Teacher is “In the Garden,” a searching ballad that connects with the themes of loss and nostalgia that inform Astral Weeks. It also harks back musically, with its breathtakingly beautiful piano playing courtesy of longtime sideman Jef Labes. (It evokes his contributions to Veedon Fleece, which rivals even Astral Weeks in the annals of Van Morrison expressing sweetly excruciating melancholy.)

Morrison has described “In the Garden” as a deliberate prompt for Transcendental Meditation, hypnotizing the listener in order to achieve “some sort of tranquility by the time you get to the end.” At the song’s climax, “In the Garden” is hushed, with Morrison singing in an impassioned stage whisper. He’s finally found the meaning of life, and he’s sharing the secret with you: “No guru, no method, no teacher,” he quietly hisses, quoting the philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti, as if his life depended upon it. “Just you and I and nature / and the Father in the garden.”

“In the Garden” is the fifth track on No Guru, No Method, No Teacher. The fourth track is not a similarly divine summit with the almighty. It’s a song called “A Town Called Paradise,” and it’s akin to Michael Corleone executing his enemies right before the christening of his sister’s baby. Morrison’s gripes are stated plainly, without the artifice of metaphor or poetry:

Copycats ripped off my words

Copycats ripped off my songs

Copycats ripped off my melody

Many Van Morrison devotees have tried and failed to wrap their heads around the confounding duality of an artist who can address the most profound mysteries of eternity in one breath, and exhibit the least admirable human traits (jealousy, narcissism, hubris, oversharing) in the next. To suggest that Morrison does this knowingly is probably giving him too much credit — he repeats this self-defeating pattern over and over as his career unfolds, without any apparent insight into his own flaws, a fatal symptom of insufficient self-awareness. His biographer Steve Turner summed up this affliction perfectly in 1993’s Van Morrison: Too Late to Stop Now: “Some people might say, ‘I’ve got a bad temper and I’m trying to overcome it,’ or, ‘I’ve got a bad temper but I don’t give a shit.’ But somebody like Van Morrison would say, ‘I’ve not got a bad temper’ — and probably shout it at you.”

I guess this should turn me off, but it doesn’t. In fact, it does the opposite. When I listen to Astral Weeks, I hear a young man who can still access the pain of adolescence, and yet has enough distance from that pain to romanticize it. This is the nostalgia of a person in his early 20s, who looks back on what is still in his immediate grasp and fantasizes about what it will one day be like to lose touch with it completely. It’s reminiscence as a form of vanity, akin to worrying a little too publicly about your 30th birthday signaling the onset of senility. I appreciate that person — we are all that person at some point — but I can no longer relate to him.

When I listen to No Guru, No Method, No Teacher, I hear an older man who has lost the ability to access his past or even comprehend the present. He has become estranged from himself, and he’s trying to reconnect with what has disappeared. But he can’t — at least not for any longer than the space of a song. Sometimes, like in “In the Garden,” he’ll briefly achieve nirvana, but nirvana is always fleeting, never eternal. Because songs are all that he has, he keeps making more of them, in the hopes of getting back to that contented headspace for a few more stolen moments.

As much as I love Astral Weeks, I find the (ultimately unsuccessful) struggle to recapture purity more compelling than purity itself.

Here’s another way that Van Morrison diverges from peers like Dylan, Young, Leonard Cohen, and Joni Mitchell: Our knowledge of his music is relatively shallow. He has released 39 studio albums in the past 51 years; his 40th, The Prophet Speaks, comes out next month. But only a small handful of those records have ever entered the popular consciousness.

Van Morrison’s music, by design, resists the crowd. The exceptions prove the rule: Moondance remains his requisite entry in the dad-rock canon, an approachably warm folk-R&B hybrid that helped to create the highly profitable “singer-songwriter” template with two other albums released in the winter of 1970, James Taylor’s Sweet Baby James and Crosby, Stills, Nash, & Young’s Déjà Vu. (To contemporary listeners, Moondance will sound like Ray LaMontagne.) Otherwise, his most well-known song (and most streamed track on Spotify by a wide margin) is the 1967 oldies-radio staple “Brown Eyed Girl,” an uncharacteristically sunny slice of summertime pop that Morrison has disowned nearly as many times as he’s performed it live.

Astral Weeks is a quintessential critics’ record, the album upon which Van Morrison’s status as an Elite Talent is based. Though even critics started to abandon him around the time of 1973’s Hard Nose the Highway, an album highlighted by a spirited and heartfelt rendition of “Bein’ Green,” which, Turner wrote, Van heard while watching Sesame Street with his daughter, Shana. Van, surely, already saw himself as being spiritually green among his peers in the rock world — a freakish outsider with a soft, felt interior.

It’s a unique curse to make a perfect album so early in your career and then become a legacy artist for whom each new record is a fresh invitation for critics to remind you that you’ll never be as good as you were at the beginning, back before you even knew what you were doing. (Lauryn Hill comes to mind as another obvious example, though I wonder whether Nas is the better comparison. What is Illmatic, after all, if not the hip-hop Astral Weeks, a youthful statement of purpose that now primarily exists as a signifier of prestige perched in the highest reaches of “best albums” lists?) In terms of how he is perceived by the self-appointed historians of rock history, Van Morrison has long been trapped inside the narrative of Astral Weeks. Which, for a guy already susceptible to self-pitying resentment, has provided only more incentive to further antagonize the people who put him there.

By the ’80s, Morrison had finally alienated his most ardent supporters in the music press, who continued to review (and frequently pan) his albums, whether out of habit, obligation, or some misguided desire to get through to Van, to motivate him to get back on track, to make another album like Astral Weeks. This push-pull between Morrison and his jilted admirers sometimes took on a comic dimension. (Robert Christgau on 1987’s jazzbo elevator-music excursion Poetic Champions Compose: “I figure if it doesn’t make me want to vomit, it must have something going for it.”)

Over time, the albums that critics haven’t understood have been written out of Morrison’s story. In his 2010 book When That Rough God Goes Riding, Greil Marcus set about (I’m quoting the back cover) on “a quest to understand Van Morrison’s particular genius.” However, this quest did not extend to 16 albums released between 1980 and 1996. He dispenses with this music in an oddly perfunctory 10-page chapter in the middle of the book. (Astral Weeks gets 19 pages, and “Madame George” by itself is expounded upon for 17 more.) “How do you write off more than 15 albums and more than 15 years of the work of a great artist?” Marcus asks rhetorically. It’s apparently not that hard, when those albums “have nothing to say and an infinite commitment to getting it across.”

I used to accept that take as common wisdom. But eventually I came to understand that the guy who made Astral Weeks kept on making Astral Weeks, only infused with the longing he felt as a grown man with infinitely more grudges, setbacks, psychic wounds, and festering regrets than anyone can possibly have when they’re 23.

Take this performance of “Comfortably Numb,” with Levon Helm and Rick Danko of the Band, from Roger Waters’s 1990 album, The Wall: Live in Berlin. (You might have also heard it in The Departed, or the episode of The Sopranos in which Christopher is killed.) This is a song that Waters and David Gilmour wrote about a drugged-out rock star’s moment of catharsis, and yet Morrison, remarkably, somehow links it back to “Cyprus Avenue.”

In 1968, Morrison could still viscerally relive his sexual awakening at age 14, “way up on, way up on, way up on, way up on, way up on, way up on, way up on” the titular street. Twenty-two years later, on a stage in Germany draped in dry ice and ravaged boomer-era rockers, Morrison was still on that lonely boulevard, hunting for a piece himself amid so many ghosts.

When I was a child

I caught a fleeting glimpse

Out of the corner of my eye

I turned to look but it was gone

I could not put my finger on it now

The child is grown

The dream is gone

When Van sang those lines, it was as if he had written them himself, all along. “The child is grown / the dream is gone” could function as a logline for much of his post–Astral Weeks work.

The following year, Morrison put out one of my favorite albums of his, Hymns to the Silence. It’s probably the last Van Morrison record I should recommend from this period, given that it clocks in at 21 songs and 95 minutes. Oh, and have I mentioned that the first track is called “Professional Jealousy” and it’s exactly as magnanimous as that title implies?

Nevertheless, Hymns to the Silence rebukes the blanket criticism that Marcus makes of this era — which is the same blanket criticism made of late-career work by most musical icons, the classic “spinning their wheels creatively” charge. Marcus quotes a Jonathan Lethem observation about how singing great rock and soul music requires “some underlying tension in the space between the singer and the song … the gulf may reside between vocal texture and the actual meaning of the words, or between the singer and the band, the musical genre, the style of production, what have you.” The implication is that Morrison lost that tension years ago.

Back in the CD days, Hymns to the Silence was divided across two discs, and it’s still helpful to approach the album that way. The first disc is composed largely of grievance songs. (Titles include “I’m Not Feeling It Anymore,” “Some Peace of Mind,” “Why Must I Always Explain?” and, hilariously, “Village Idiot.”) The second disc, meanwhile, is made up mostly of songs about love, God, and aspiring to those blessed concepts. In the spoken-word piece “On Hyndford Street,” he describes a scene that could have unfolded back on Astral Weeks.

On Hyndford Street

Where you could feel the silence at half past eleven

On long summer nights

As the wireless played Radio Luxembourg

And the voices whispered across Beechie River

In the quietness as we sank into restful slumber in the silence

And carried on dreaming, in God

In Van Morrison songs, silence denotes an elevated state. (“On Hyndford Street” concludes with Morrison repeating a phrase that recurs in other songs of his: “Can you feel the silence?”) Perhaps only a misanthrope would associate silence with godliness, unless the voices he yearns to escape come from inside his head — the ones that continually push him away from the divine, or the best parts of himself.

That’s what I hear when I play Hymns to the Silence — the tension between who Van Morrison wishes he could be, and who he actually is.

What if Van Morrison had tried to out–Bruce Springsteen Bruce Springsteen?

I think about this scenario sometimes: Morrison went into hiding in the mid-’70s, after the public and the press cruelly dismissed the sublime Veedon Fleece as a self-indulgent collection of impenetrable dirges. He laid low in Northern California and tried to get his drinking under control. Recording sessions in 1975 produced some worthwhile and lively numbers — like the self-explanatory “Naked in the Jungle” — but he chose not to put them out. Instead, according to Turner, he read obsessively about Jungian psychiatry and Celtic history, and studied under a so-called “tension expert” to help him release his own considerable inner strain.

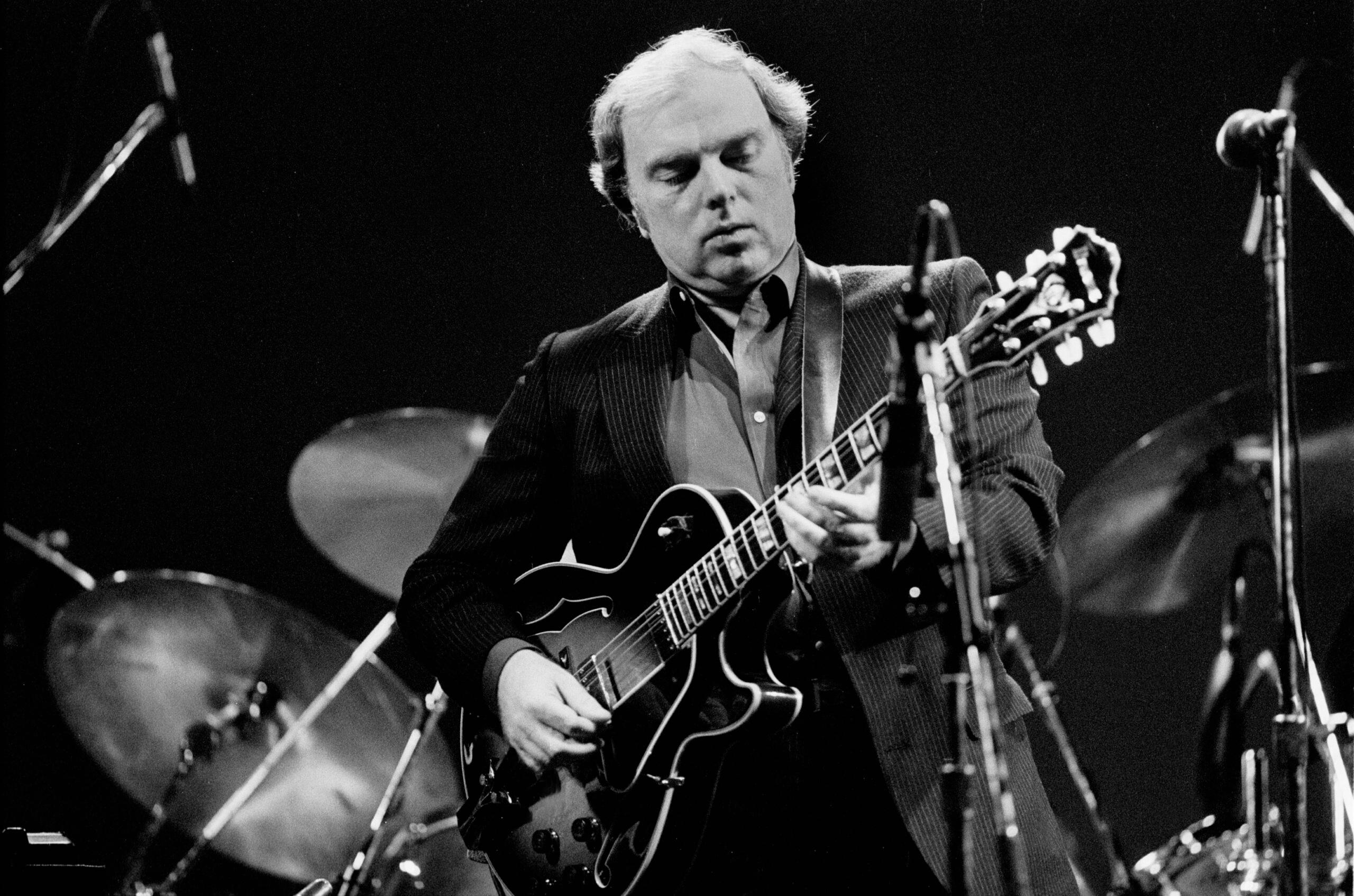

Morrison didn’t make a significant public appearance during this time until November 1976, at the Band’s historic “Last Waltz” farewell concert at Winterland in San Francisco. After initially agreeing to send off his old Woodstock running mates, Morrison had a last-second bout of stage fright, and — according to his manager Harvey Goldsmith — had to be literally kicked out on stage.

Obviously, this is an iconic performance, as much for the power of Morrison’s voice as for the way he transcends his own frumpiness — the purple suit, the paunch, the receding hairline, the high kicks, the nonchalant walk-off at the end, it all works in spite of the usual mathematics of conventional rock-star glamour. I wish I could watch The Last Waltz without knowing anything about Van Morrison. How surprising would it be to hear, well, Van Morrison’s voice come out of that guy? It’s a setup that has been exploited time and again on America’s Got Talent — the overlooked schlub who sings like a champ — but rarely traced back to the single greatest example of this phenomenon, The Last Waltz.

When the movie finally arrived in theaters in the spring of 1978, it predated the fourth Springsteen album, Darkness on the Edge of Town, by a couple of months. On that LP, Bruce moved past the loose-limbed, horn-heavy arrangements of his early work to embrace a more full-on arena rock sound; that is to say, he sounded less like Van Morrison and more like himself. And, right on cue, Van the Man himself had returned and proved that he still had it in him to be a show-stopping soul man in The Last Waltz. The table was set for him to take back what the alleged thieves had taken from him.

For a while, Morrison finally seemed capable of giving the people what they wanted. That fall, he released Wavelength, his most accessible album since Moondance, a more or less straightforward collection of punchy pop-rock songs that became one of his best-selling albums at the time. Wavelength’s reputation has suffered somewhat since then, but I really like it, especially the song “Natalia,” which is sort of a yacht-rock redux of “Brown Eyed Girl.” And then there’s “Venice U.S.A.,” a fever dream about a happy day at the beach in which Van sings “dum derra dum dum diddy diddy dah dah” approximately 6,000 times in the space of nearly seven minutes. It’s impossible to communicate on paper how eloquent “dum derra dum dum diddy diddy dah dah” is when Van Morrison sings it. Morrison, like Springsteen, is an exemplary lyricist who nonetheless seeks to go beyond words and into the pure emotional abstraction of guttural noise. (For Springsteen, the noises of choice are uhhhhh and waaaaah, whereas Van prefers la and dum and other, more musical utterances.) In great writing, you must show rather than tell, and sometimes noises show better than words. Of all the lessons Bruce learned from Van, this is the most valuable.

While competing with Springsteen and Elvis Costello doesn’t appear to have been his conscious goal, Morrison had successfully reinserted himself into the mainstream rock conversation. His next album, 1979’s Into the Music, even won back the critics by evoking the albums of his past, starting with the title, which nodded to “Into the Mystic” from Moondance.

What if Van Morrison had continued making albums in this vein? What would his career look like now? Would his reputation beyond diehards be wider and deeper than just Astral Weeks? Would he be slightly happier?

I’m glad Van took the path that he did, which led him in February 1980 to a haunted monastery in the French Alps. For 11 days, Morrison and his band experimented with an open-ended mélange of atmospheric jazz and rough-and-tumble R&B, as well as dashes of new age music. While he couldn’t have known it at the time, Morrison was dreaming up the next 38 years (and counting) of his career.

Of course, the album birthed at these sessions, Common One, tanked commercially. Critics hated it, too. Once again, he ditched the easy hooks and feel-good pub rock and leaned into semi-improvised hymns that drifted philosophically past the 10-minute mark. While time, once again, proved to be on Van Morrison’s side — he loved Common One, and now so do many of his fans — in the short term it looked like yet another incomprehensible folly.

The most extraordinary song from Common One is “Summertime in England,” a 15-minute epic that includes elements of everything Van Morrison has ever done, and perhaps ever will do. It starts out rapid and alive, like a wild James Brown live bootleg. Morrison scats about the poets Wordsworth and Coleridge “smokin’ up in Kendal”; in the next verse, William Blake and T.S. Eliot are smokin’ up, too.

Without warning, the music downshifts into a dreamy soundscape not unlike the stately music Van would come to favor on his subsequent ’80s albums, though the vibe here is more In a Silent Way than Avalon Sunset. Suddenly, a string orchestra dramatically barges in, like a Gamble & Huff production. Shortly after that, a church organ materializes, invoking the Holy Spirit. It’s impossible to tell what is composed and what just happened to occur in the moment, what is intentional and what is accidental. It’s an absolute mess and a thing of unvarnished exquisiteness.

All I know is that Van sounds free, like he’s finally found what he’s been looking for, and will push this song to the breaking point in order to revel in it for as long as he can, before he has to go back to being Van Morrison. “Can you feel the silence?” he asks and asks as the song drifts toward the fade-out. But I always care more about whether he can.