She holds it together pretty well, Julia Roberts, for the first three minutes of her Oscar acceptance speech. It’s March 2001, and Kevin Spacey has just called her name as the Best Actress victor for Erin Brockovich, and her dress is unwieldy enough that her boyfriend at the time, Benjamin Bratt, is compelled to help her up the stairs. She makes it. She gives Spacey a big hug. She clutches her Oscar and steps up to the mic. Big laugh. Big smile. “Thank you, thank you ever so much,” she begins. “I’m so happy.” It is plenty, charisma-wise, but it is not yet The Most. Though you know The Most is coming.

The 2001 Academy Awards are running long, as usual; veteran Oscars music director and conductor Bill Conti goads Roberts to wrap it up, and Roberts is just as quick to repel these efforts while referring to him as “Stick Man,” on account of his baton. As in, “Sir, you’re doing a great job, you’re so quick with that stick, so why don’t you sit. ’Cause I may never be here again.” (The next day, Roberts will send Conti flowers and chocolates.)

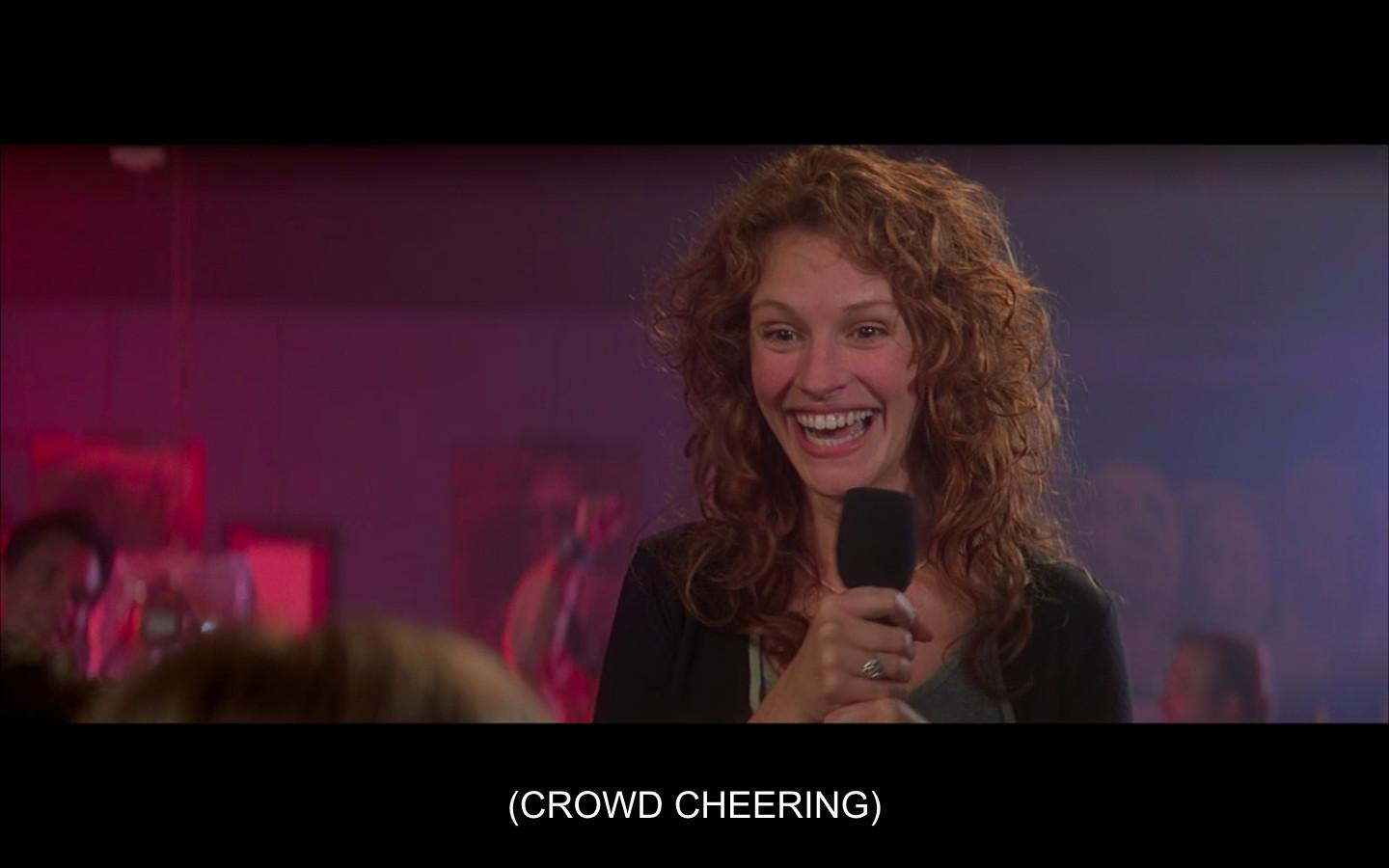

She praises her fellow nominees (Joan Allen, Juliette Binoche, Ellen Burstyn, and Laura Linney) while marveling at the shininess of her statue. (“I can’t believe this is … this is … um … this is … like … pretty.”) She thanks “everyone I’ve ever met in my life.” She playfully spars further with Stick Man and his impatient cohorts. (“Turn that clock off, it’s making me nervous.”) But she doesn’t truly erupt until she is praising Erin Brockovich director Steven Soderbergh, who indeed will win Best Director this same night, for another movie. “I thank you … for really making me … feel … so …”

Look out. “Ha ha ha!” bellows Julia Roberts, finally erupting into that iconic, massive, jaw-unhinging smile-laugh combo, her voice quadrupling in both volume and delight. “AAAAH HA HA!!” She flails her arms wildly, adorably. “I LOVE it up here!” Soon, to Stick Man’s great relief, she finally wraps it up: “I love the world, I’m so happy, thank you!” And as ever, the world ferociously loves her back.

The calculus of when ecstatic Oscar acceptance speeches veer, in the public imagination, from The Most to Too Much is arbitrary and cruel — recall the unwarranted backlash to Anne Hathaway’s “It came true” back in 2013. But Julia Roberts is immune, is exempt, is indifferent to the laws of physics and attraction and superstar longevity. She was America’s Sweetheart long before she appeared in a 2001 rom-com called America’s Sweethearts; even today, with far fewer roles and far less public visibility, it feels wrong to describe her renewed prominence in 2018 as a “comeback,” exactly.

As the tremulous centerpiece of November’s unsettling Amazon thriller Homecoming, she is mesmerizing no matter the aspect ratio, deploying that $30 million–insured smile minimally, but with maximum impact. On Friday, she stars opposite Lucas Hedges in the dark addiction drama Ben Is Back, which given its surface similarity to other 2018 contenders seems unlikely to rocket her back to full AAAAH HA HA Oscar glory, but fits her quite agreeable pattern of hitting hard without swinging too hard, without flailing, without diluting the high drama by overdoing it.

At the least, both the show and the movie have vaulted her back into a national conversation she never quite left, even if you hadn’t actually spoken her name in years. In the past decade or two, America has crowned (and sadistically dethroned) new Sweethearts, but none with quite her intensity and vivacity. Her dominance in ’90s romantic comedies, especially, is such that the likes of Netflix and Crazy Rich Asians have only recently begun an attempt to restore the genre to its full glory, and without any one star remotely approaching her caliber, then or now or likely at any point in the future.

Julia Roberts is 51, and her modest output in the 2010s is relatively grimmer in tone, though a 4-year-old’s birthday party would be grimmer in tone compared to the endless string of blinding-grin joybombs that launched her to megastardom. But she flirted with alluring darkness even at her peak, just as her radiance can still illuminate her grittier roles since. To revisit her filmography now is to risk both exhaustion and over-elation. So yeah, let’s do that. Hers is not the blueprint, but the gleefully broken mold. The cliché is they don’t make ’em like her anymore. The reality is they never made another of ’em like her in the first place.

There she is, Miss America, her majestic tangle of power-ballad hair tied back as she clutches a Miller Lite on a dock in the 1988 rom-com Mystic Pizza, comparing a comet to “a sperm” and musing uneasily about her future. “How the hell do I know where I’ll be 10 years from now?” she laments. “I can be dead for all I know. All I’ve got is this [points at enormous smile] and these [holds up remaining three cans of Miller Lite].” Big, brassy laugh. She runs off. The world chases after her. (And just for the record, 10 years later, she would star in the 1998 dramedy Stepmom opposite Susan Sarandon, wherein they debate the pros and cons of taking a teenager to a Pearl Jam concert on a school night.)

Roberts debuted, uncredited, in 1987’s little-seen farce Firehouse and first cracked the prestige tier as a Best Supporting Actress nominee for 1989’s weepy and whimsical Steel Magnolias, in which her aesthetic is All Pink Everything (her wedding colors are “blush and bashful”) and her function is (spoiler alert) to die. Which she does, with minimal histrionics, leaving the big laughs to Dolly Parton and the bigger breakdowns to Sally Field. But not before she forcefully delivers the movie’s thesis, and her own: “I would rather have 30 minutes of wonderful than a lifetime of nothin’ special.”

And then came 119 minutes of wonderful, in the form of 1990’s Pretty Woman, featuring the all-universe Julia Roberts mega-laugh, the sort of singular movie-star moment that launches careers, and also launches myriad websites to remind that you that the moment was unscripted.

Every last second of director Garry Marshall’s beloved Heartless Businessman Meets Heart-of-Gold Prostitute fable, which earned Roberts her second Oscar nomination, is absurd and spectacular. Richard Gere’s character is Bain Capital personified; it’s fun now to pretend that the company he spends most of the movie trying to take over and dismantle is Toys R Us. But who cares about him? There is Julia Roberts guffawing at the grape-smashing scene in I Love Lucy, and gnawing a pancake like a doughnut, and crooning Prince’s “Kiss” in the bathtub, and pumping her fist and shouting “WOO WOO WOO” at a polo match, and turning the word “Really?” into the rom-com line delivery of the century. You will never enjoy opera one-tenth as much as you enjoy watching this woman enjoy opera.

Pretty Woman is so monolithic that even Roberts’s many subsequent date-night blockbusters are overwhelmed by it and forced to contend with it by subverting, in increasingly ridiculous ways, her immediate and unchallenged status as All-Time Rom-Com Queen. My Best Friend’s Wedding, from 1997, turns her into the villain (“I’m pond scum!” she mewls, adorably) opposite Cameron Diaz in what is essentially romantic-comedy Alien vs. Predator. She tries her best to steal Diaz’s big karaoke scene right out from under her, but Rupert Everett eventually steals the movie from them both.

Climactically, she hijacks a bread truck; in 1999’s Runaway Bride, reunited with both Marshall and Gere, she makes her final escape from the altar via FedEx van. Runaway Bride is most definitely Too Much, in terms of both its multiple Pretty Woman callbacks (there is another cute negotiation between Roberts’s small-town heartbreaker and Gere’s pompous big-city newspaper columnist, and the best line is once again “Really?”) and its relentless whimsy. No contrivance in Pretty Woman is more ridiculous than the first 10 minutes of Runaway Bride, in which everyone on screen is reading USA Today at all times.

It all goes down like your fifth piece of wedding cake and either peaks or bottoms out with a very meta heart-to-heart wherein Joan Cusack, as the wacky best friend, muses on the Julia Roberts mystique in general: “I think sometimes you just sort of spaz out with excess flirtatious energy.” (Also: “I think you’re like, ‘I’m charming and mysterious in a way that even I don’t understand.’”) They debate the merits of “quirky” vs. “weird”; to wrap up, Roberts makes a “duckbill platypus” face that makes her look alarmingly like Angelina Jolie.

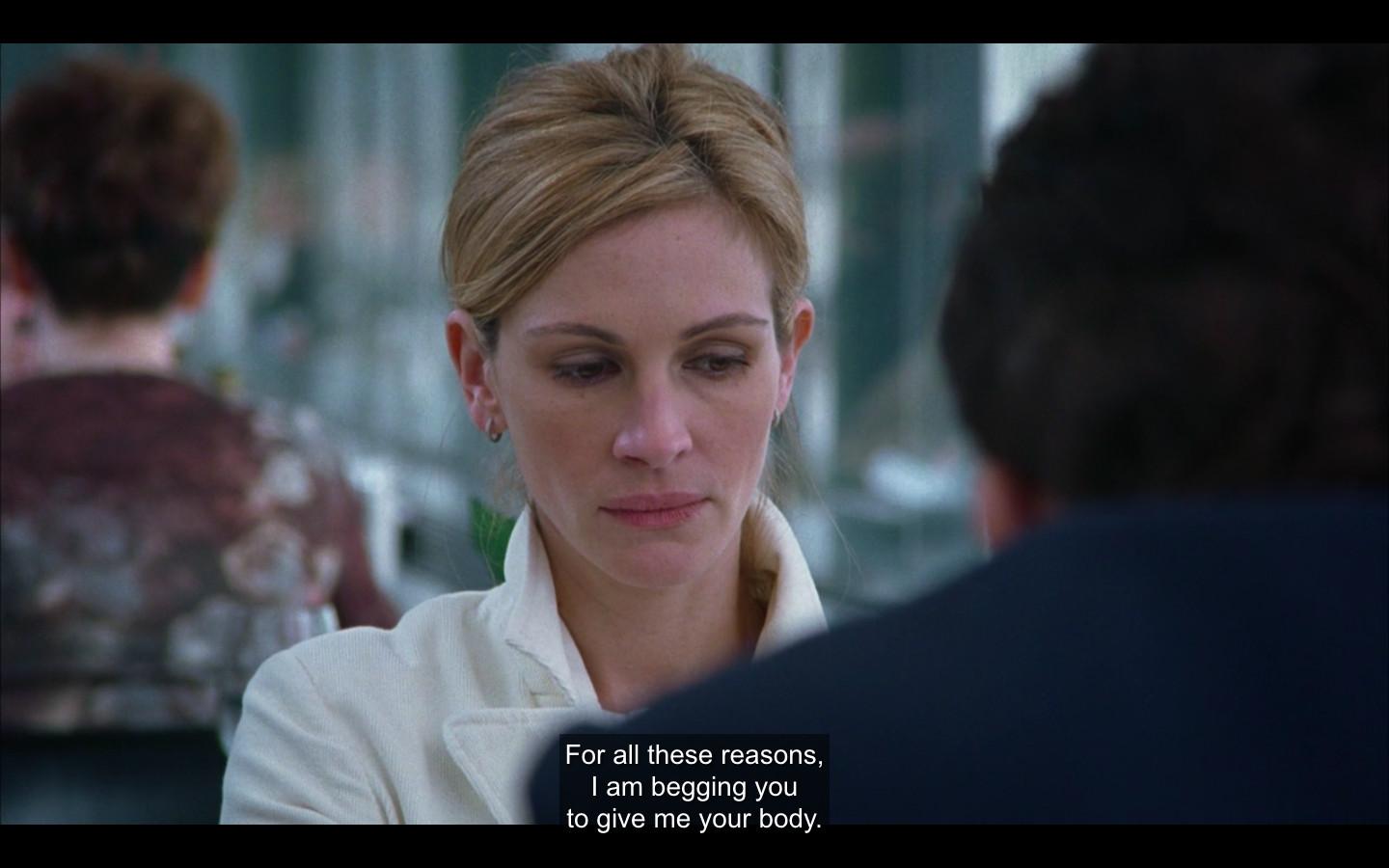

Her other blockbuster 1999 rom-com is much better, in part because Roberts’s character is much icier. Notting Hill solves the Pretty Woman Shadow Conundrum by making her a fictional movie star and Hugh Grant a gobsmacked commoner — by this point her very presence in a rom-com is so intimidating that all you can do is make the whole movie about that intimidation. (The Notting Hill poster is instructive.) Perhaps you’ve forgotten this film’s weirder notes, like the tabloid revelation of a sex tape or the scene in which Roberts attempts to steal a brownie at a civilian dinner party by out-sad-sacking a recently fired stockbroker and a lady in a wheelchair. But you have definitely not forgotten her “I’m also just a girl, standing in front of a boy, asking him to love her” speech, which is all the more poignant for the fact that she is (very briefly) rejected.

There was nowhere else to go from there, romance-wise, for her or practically anyone else. To Roberts’s credit, she didn’t much try, save a few survivable trifles like her brief stint playing backgammon with Bradley Cooper on a plane in Marshall’s generally unsurvivable 2010 ensemble farce Valentine’s Day. (She survived 2016’s Mother’s Day as well despite wearing this wig.) Indeed, from the moment Pretty Woman hit big — like, nearly half a billion dollars worldwide big — she began filling out her filmography with darker dramas that nonetheless never felt like cheap playing-against-type tricks. She never did a huge, oversold As You’ve Never Seen Her Before push toward gritty authenticity; she showed range from the start without insisting on telling us all about it.

Roberts did 1990’s original (and far superior) Flatliners. She did 1991’s abusive-husband thriller Sleeping With the Enemy, the sort of movie that ends with the embattled heroine crying while firing a gun; that year she also did the dramedy Dying Young in which (spoiler alert) she doesn’t. Unless you’re a superfan of Steven Spielberg’s wobbly 1991 Peter Pan rewrite Hook (you’re not), the most rewarding non-canon Julia-themed rewatch from this era is 1993’s legal drama The Pelican Brief, given its Homecoming-esque paranoid-thriller vibe and myriad mazelike overhead shots of law offices and whatnot. We meet Roberts’s character in a law-school class taught by her secret boyfriend, Sam Shepard, and also attended by her good friend, Cynthia Nixon.

Directed by Alan J. Pakula and based on the smash John Grisham novel, The Pelican Brief is neither the director’s nor the author’s best work. But it has an eerie present-day resonance (the plot involves a corrupt president trying to stack the Supreme Court while he strong-arms the director of the FBI) even at its wackiest (a sitting Supreme Court justice is assassinated, by Stanley Tucci, in a porn theater).

Roberts, meanwhile, is fully committed, whether she is wailing in the aftermath of a car bomb or nicely underplaying her natural chemistry with costar Denzel Washington. She spends much of the movie in hiding — frumpy wigs, fanny packs, Mets hats, etc. — until, presumably, a studio exec intervened and she is allowed to be her usual radiant, glamorous self provided she mostly doesn’t leave the library. Your reward for hanging in with the convoluted plot for nearly two and a half hours is as follows:

“I love my life,” Roberts would later declare at the 2002 Oscars, announcing Washington’s own Best Actor win for Training Day, another adorably solipsistic moment for which she avoided, by sheer force of charismatic will, any substantial backlash. She was a made woman at that point, both within the Academy and without.

Her lousier genre stuff (the 1996 horror flick and rare box office bomb Mary Reilly, the lurid ’97 Mel Gibson turkey Conspiracy Theory) made nary a dent. And what made her coronation via 2000’s Erin Brockovich so enjoyable is that it didn’t play out as an overhyped Comedy Star Gets Serious stunt, or an eye-rolling, blunt-force statue grab à la Leonardo DiCaprio in The Revenant. No bears were harmed, no overacting deployed. The movie was, instead, a natural extension of the endless starburst Julia Roberts charm offensive, just now with weaponized cleavage and a throwback to her teased-hair heyday and Steven Soderbergh’s abiding mutual love affair with natural light and a truly heroic amount of profanity.

“Shithead.”

“My fucking neck.”

“That stupid bitch.”

“What the fuck did you do with my stuff?”

“I’m not talking to you, bitch.”

“You are living next door to a real live fucking beauty queen.”

“Have a fucking cup of coffee, Ed.”

“Oh, bite my ass, Krispy Kreme.”

[Yelling at snooty lawyer.]

“Two wrong feet and fucking ugly shoes.”

[Yelling at phone.]

“Oh, you fucking piece of crap with no signal.”

While technically a conspiracy thriller, Erin Brockovich, save for exactly one anonymous threatening phone call, indulges no paranoia. And Roberts, playing the titular real-life legal clerk and amateur sleuth who unravels an environmental disaster perpetrated by “those arrogant PG&E fucks,” has no worthy adversaries. Instead, you get to watch her kick everyone’s asses in slow motion. Including her love interest, a preposterously beatific biker dude played by Aaron Eckhart, who is just a boy, etc., etc., etc.

Roberts’s best Erin Brockovich moment, in fact, which alas gets no YouTube love in the face of all her delightful tirades, is one of her least verbose: It’s just her listening and driving and crying and super-smiling as Eckhart recounts the story of how she was working so hard that she missed her baby daughter saying her first word.

There is likewise no melodramatic courtroom confrontation, just a goofy and triumphant scene in which Roberts gets to tell those snooty lawyers that she scored the case-winning evidence by giving “634 blowjobs in five days.” (“I’m really quite tired.”) You never forget, for one second of Erin Brockovich, that you are watching a movie star, but you likewise never feel like you’re watching a movie star trying to sweet-talk herself into a higher, haughtier tier of prestige. She was already there, apparently, entrancing and/or sassing the bejesus out of everybody, like always. She practically spends the whole movie — and spent her whole first Hollywood-royalty decade — with the Oscar statue already in her hands.

Sophisticated Julia Roberts fans will tell you that her best role is actually in 2001’s Ocean’s Eleven, another Steven Soderbergh flex and indeed a quite impressive Quality Over Quantity situation, in that despite very limited screen time, she’s the only person who fazes George Clooney for a second, with a steely and whooping-laugh-free comeback for everything. He mentions the divorce papers sent to him in prison: “I told you I’d write.” He tries to win her back: “You’re a thief and a liar.” He asks whether her new casino-magnate boyfriend makes her laugh: “He doesn’t make me cry.”

The best line delivery in the whole movie is when she says, “He does?” to Brad Pitt. Take another sophisticated Julia Roberts fan’s word for it. She would return for 2004’s extremely indulgent Ocean’s Twelve, never more indulgent than in the scene in which her character, Tess, is forced to impersonate the superstar actress Julia Roberts, to whom Tess, as she is told, bears an uncanny resemblance. It’s that kind of movie. Not appearing in 2007’s Ocean’s Thirteen at all is one of her savvier career moves.

Post-Oscar, she graced the early 2000s with one last high-volume burst of activity, featuring no big hits but no egregious misses. I’ve got a soft spot for the Tarantino-lite high jinks of 2001’s The Mexican, billed as a highest-possible-wattage summit between Roberts and Pitt, but most notable for her many feisty scenes with James Gandolfini as a sensitive hitman, especially the one in a diner that starts out with her whispering, “Are you gay?” Follow-up question: “Are you full throttle?” Gandolfini’s reaction is everything your heart desires.

Confessions of a Dangerous Mind, George Clooney’s somewhat darker 2002 directorial debut, offers the remarkably rare occurrence of (spoiler alert) a Julia Roberts death scene. She took a massive pay cut for that one to help her old friend out; not so for 2003’s Mona Lisa Smile, a goopier and broader inspiring-teacher Dead Poets Society deal for which she was reportedly paid a record $25 million, a bonkers figure that would be used against her when subsequent films did poorly. But by then she was doing far fewer movies in general. The full-throttle phase of her career concludes in 2004, with Ocean’s Twelve, yes, but more importantly, or maybe just more viciously, with Mike Nichols’s Closer.

If it’s the meanest and lewdest possible iteration of Julia Roberts you seek, seek no further; if you’ve longed to watch Jude Law type “sit on my face fuckboy” to Clive Owen via an online chatroom called “London Sex Anon,” this is literally the only movie for you. Rounded out by Natalie Portman, these four beautiful and terrible people spend an hour and a half saying unfathomably nasty things to one another; even the meet-cute between Roberts and Owen hinges on him saying the words “cum-hungry bitch” to her. I hope to god this scene wasn’t unscripted.

Their eventual breakup — the centerpiece of a movie that is somehow entirely breakups — is spread out over four agonizing scenes featuring a great many more 20-pound swears, by which time Roberts, by design, is a shuddering mess. The closest thing you get to a classic J.R. smile is when her divorce is final, which, of course, it isn’t. As a darkest-timeline Pretty Woman, this was a cruel trick worth pulling exactly once. I’m just a guy on a website punting this film into the sun.

She got choosier from there, though not necessarily better. She played a right-wing Texas debutante in 2007’s Charlie Wilson’s War, drawling Aaron Sorkin dialogue about arming Afghans to fight the Soviets while she plumps her eyebrows with a paperclip. Her Southern accent sounds less fake than usual (strange, given that she’s from Georgia), but her bizarre star-crossed romance with Tom Hanks is not the supernova summit you’re hoping for, and the real-life-as-political-satire tone is all over the place. (She reteamed with Hanks for 2011’s way goopier Larry Crowne, which turned out even worse.)

But by then her leading-lady days were mostly behind her, to the dismay of a movie industry that kept trying and failing to replace her. She started a family; she kept the torch lit on account of there being nobody to pass it to. A quote from a cautious 2009 New York Times piece about Roberts’s role in that year’s semi-comeback vehicle Duplicity: “‘Nobody has stepped into the vacuum,’ said one female producer, who spoke on condition of anonymity to protect her future hopes of casting the likes of Reese Witherspoon, Amy Adams and Scarlett Johansson.” Another quote from that producer: “Right now, people are desperate for the heir apparent to be Katherine Heigl.” Sheesh. It’s overselling to say that peak Julia Roberts had no peers (peace to the god Meg Ryan) and no disciples. But her stature is such that her absence is its own disquieting sort of presence.

Duplicity mashed her and Owen back together for some fizzy con-artist action best remembered on the internet for this GIF of an especially alarming Julia Roberts mega-smile. But the closest she’s gotten to a throwback dominating role in the past decade or so is, of all things, the 2010 adaptation of the hit book Eat Pray Love, directed by, of all people, Ryan Murphy. Verily, this is the ne plus ultra of first-world problems, a nearly two-and-a-half-hour tourism-as-narcissism bonanza featuring loving close-ups of Roberts’s mouth as she slurps pasta, a meet-cute with an elephant, James Franco as a stateside love interest who makes the whole tourism-as-narcissism plot far more agreeable, many fine floppy hats, and a whole lotta fuckin’ meditating.

That Roberts makes it all tolerable is nothing short of astounding. From the start, she’s working awfully hard (as is Richard Jenkins), and as she traipses from Italy to India to Indonesia, she ends up pulling this movie from a fiery hot-take hellscape as though she’s clinging to a helicopter skid. As a flexing of pure star power in a hopeless losing effort, this is “LeBron in the 2018 Finals” stuff, with the role of J.R. Smith filled by (another) random well-meaning white woman wearing a bindi. It’s all very relaxing, which will come in handy after you watch her yell many variations on Eat it, you fucker, eat that catfish at Meryl Streep in 2014’s August: Osage County, which flirts with disaster just as flagrantly from the opposite end of the emotional spectrum.

Completing the great Julia Swears Uncontrollably trilogy begun by Erin Brockovich and Closer, this adaptation of Tracy Letts’s Pulitzer-winning 2007 play is … faithful? Not faithful enough? Too faithful? Did they cast Ewan McGregor and Benedict Cumberbatch by accident? “We fucked the Indians for this?” Roberts muses, dourly surveying the dour Oklahoma landscape at the onset of a highbrow Family Reunion From Hell scenario that climaxes with her yelling, “Give me the fuckin’ pills!” before tackling poor, terrible Meryl like a middle linebacker. (FUN FACT: Sam Shepard plays the drunk patriarch who sets all this calamity in motion, making him the only person in history to play both Julia Roberts’s boyfriend and her father. Separately.)

It’s all acting-masterclass misery porn, never quite overcooked enough to qualify as unintentional comedy but nowhere near as poignant and cathartic as it imagines itself to be, up to and including the moment when Roberts tosses aside her own plate of catfish and snarls, “You don’t want to break shit with me, motherfucker.” Correct. There is a dark alternate universe where she’s only made dead-serious tragedy bacchanals like this for the past 20-odd years just to prove there’s more to her than rom-com sweetness. Be grateful she gets in this mood only every decade or so.

Which means she’s due, and her other recent roles (a villain in 2012’s silly fairy tale Mirror Mirror, the director of a Mad Money–esque TV show in the overcooked 2016 drama Money Monster, a proud mom in 2017’s family-friendly tearjerker Wonder) didn’t quite qualify. She’s having a better 2018. What makes Roberts so effective in Homecoming is that she dials her natural charisma way back (with help from both her wig and the dazed expression endemic to someone starring in a Sam Esmail puzzle-box construction) but doesn’t turn it off entirely. Her many scenes opposite Stephan James have an unforced flirtatiousness that creeps you out all the more for how familiar it feels. She’s a rat in a very fancy auteurist’s maze, and she underplays it nicely even at her most overwhelmed.

Ben Is Back, out Friday, opens with yet another radiant Julia Roberts smile, and she keeps grinning with a desperate fierceness even after her drug-addict son Ben (Hedges) shows up from rehab unexpectedly, the outline of a bleak Oscar-bait tragedy visible from the moment they embrace. Written and directed by Peter Hedges (Lucas’s father), the movie shrewdly deploys both her sunny side (Ben tells some dumb story about smelling a fart in a car, and she nervously oversells her laughter like he just handed her another Oscar) and her dark side (“I hope you die a horrible death,” she hisses at a confused doctor in a mall food court, and she’s got her reasons).

The story beats here — the terrified initial response from the rest of Ben’s family, the first signs he’s cracking, the 12-step meeting, the evil drug dealer out for revenge, the despair, the chase, the for-your-consideration meltdowns — are familiar but don’t linger long enough to harden into clichés. “Just tell me where you want me to bury you,” Roberts snaps at her son after driving him to a cemetery, one of several chilling scenes that would over-ripen if they were even 20 seconds longer. She vomits, she screams, she barters drugs for information, she digs in a dumpster, she flips out in a police station, and she anchors a genuinely agonizing final five minutes that reward your suspension of disbelief the same way she always has: richly. Improbably. Thoroughly.

It’s a Message Movie. It’s a little tidy, and things get a little wayward by the time there’s a third party on an iPad tracking cell phone locations like an after-school-special version of Mission: Impossible. It’s rough sledding emotionally, and it loses something when it tries to soothe you, even if you’re dying to be soothed. It is unlikely to serve as any sort of gala Julia Roberts recoronation, but she does this material justice by realizing that a recoronation is hardly necessary. Only she can fill her own vacuum. She can still give you The Most, though sometimes even The Most is not enough. But 30 years on, it’s somehow still not Too Much.