Back in September 2018, Bill Simmons and Shea Serrano used the Rewatchables podcast to examine the revolution that was the 2008 film Taken. According to them, what made this revenge thriller so special was first and foremost its casting of Liam Neeson as the vengeful father, on the hunt for the criminals who kidnapped his daughter in Paris when all she wanted to do was see U2 live in concert. Better known in the ’80s and ’90s for playing sensitive lovers and heartbroken dads, Neeson became an unlikely action hero and never looked back.

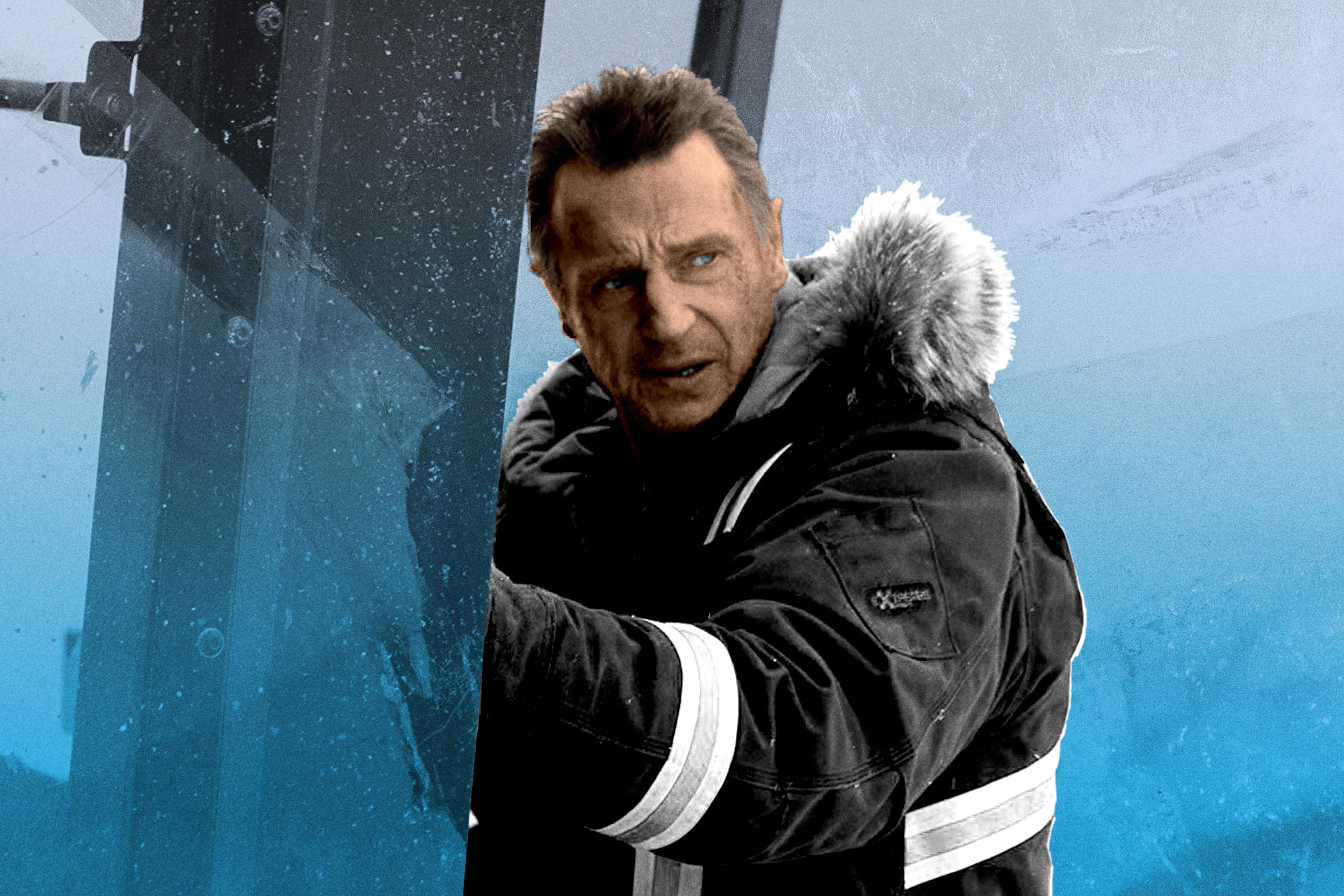

Many critics compared Hans Petter Moland’s film In Order of Disappearance (Kraftidioten) to Taken when it premiered on the festival circuit in 2014, while recognizing that Moland’s dark humor took the typical material in original directions. Again, a father (played originally by Stellan Skarsgård) seeks to avenge a family member—here, his murdered son—but instead of being a retired special-ops agent, dad is merely a snow-plow driver in a tiny, mountainous Norwegian town. Inevitably, Neeson takes on the part in Moland’s American remake of his own film, retitled Cold Pursuit and now set in the fictional town of Kehoe, Colorado. After deploying his “very particular set of skills” in the Taken franchise and fighting for the weak in Non-Stop (2014), Run All Night (2015), and The Commuter (2018), Neeson returns more directly to his everyman origins.

As the unassuming Nels Coxman, Neeson is distant and unemotional, and Nels’s speech when he receives a Kehoe Citizen of the Year award is a cute ramble defined by humility. His wide-eyed cluelessness when his son Kyle (Micheál Richardson, Neeson’s real-life son) is found dead from an apparent overdose therefore looks, at first, like the reaction of a man raised on old-fashioned ideas of masculinity: Instead of crying, a man must use violence to deal with his grief. It is impossible not to tie this characterization to Neeson’s bizarrely hazardous and not thought-through confession Monday during a press junket interview that he himself had once sought to commit murder to avenge a female friend who had been raped. While it’s a shame that Neeson didn’t qualify his week-long roaming of streets armed with a cosh as being tied to a certain type of masculinity, what has rightly upset public opinion much more is how he failed to pinpoint that his desire to attack the first black man to show any aggression toward him was, in fact, racist. He has since expanded on his story, explaining that although he had then been “shocked” by his initial response, he is “not racist” and would have reacted in the same way if the rapist had been white. But one can only take his word for it—and after such a messy and thoughtless attempt at “open[ing] up” a discussion, his status as a movie star and public figure has been overwhelmed by the week’s events.

Neeson’s interview hangs over Cold Pursuit, but the film is confused on its own terms as well. The uncertain tone it seeks out once Nels starts hunting his son’s killers complicates any potential critique of his typically male and violent urge. Nels’s emotional stiltedness isn’t questioned, but rather dismissed as secondary to the amusing mess he makes of his victims because of his inexperience in the killing business. When his first casualty wakes up from what Nels thought was a thorough strangulation, the father jumps back on him, confused but determined to get the job done. This scene was much funnier in the fast-paced trailer, without the context of Nels’s unsettling stiffness (and the Independent interview).

Cold Pursuit’s tone gets only more scattered as the film goes on and shifts its attention to the people responsible for Kyle’s death. The contrast between Nels’s cold-blooded vengefulness and the frivolity of drug lord Viking (Tom Bateman) is amusing, but more thanks to Bateman’s relentlessly comedic performance than any fine ironies in the script. Determined to turn his young son Ryan (Nicholas Holmes) into a successful man, Viking encourages him to read Lord of the Flies and forbids all sweets from his diet. Bateman looks the part of the alpha-male villain with his slicked-back hair and wild behavior, and his line readings convince us that Dad means every word. But, strangely enough, the film only barely taps into the emotional potential offered up by its parallel father-son relationships. After kidnapping Ryan, Nels finds himself reading him a snow-plower manual as a bedtime story, and the tenderness of this moment between a bereaved parent and a little boy starving for fatherly affection got to me. Yet as though the film were allergic to any real feeling, Ryan suddenly asks, “Have you ever heard of Stockholm syndrome?” and the tension deflates into a cheap joke. Free from sorrow, Nels’s vengeance looks a lot like senseless violence.

Just as Nels’s reactions fall short of Robert De Niro’s awkward and violent temper tantrums in Jackie Brown—Tarantino being a clear influence here—Cold Pursuit itself doesn’t manage to make the story’s calculated diversions look like the realistic yet absurd bad luck that drives QT’s classic. Since apparently Viking’s ludicrous gang isn’t punchy enough to sustain an entire film, another clan is added to the mix—and not just any clan. Serbians from the original film are replaced by Native Americans here. White Bull (Tom Jackson) finds his men involved in Nels’s rampage directly because of Viking’s racism: Wondering who could possibly be killing his men, Viking decides on the indigenous people (who he always refers to as ‘Indians’) because of an old rivalry between his father and the group’s leading elder. Without any evidence, he kills White Bull’s son and hangs him on a road sign.

At once a perhaps unconscious reference to the much-maligned Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri (the film’s ironic tone and theme of revenge enhance the comparison), a play on gangster-film genre tropes, and an attempt at social critique, this new element isn’t handled with much delicacy and ends up sinking the ship. Ridiculing openly racist characters like Viking, which the film does repeatedly, isn’t enough. In its characterization of its indigenous characters, Cold Pursuit is casually, but nevertheless blatantly, racist. White Bull and his team aren’t presented as people as much as elevated to a mystical status. They don’t often speak, instead moving through space with silent grace. In a couple of scenes, a pair of Native henchmen are seen being more casual, but when the younger boy smokes reservation-grown weed, his partner criticizes him for not choosing instead the better, white variety. This young man’s choice is reduced to a knowing joke about capitalism (maybe?) and its symbolic value judged superficial.

Cold Pursuit focuses on cliché ideas of Native American spirituality and places these othering conceptions high above the reality of discrimination. Even if a few scenes are dedicated to showing the ruthless commercialization of Native culture, White Bull functions like an ideal of Native identity as defined by the white oppressors, rather than as a flesh and blood human. In the final shoot-out, he moves in slow-motion through a wall of bullets, as though magically immune to physical harm. Making historically persecuted people seem mythical and invincible to racially motivated assault is a convenient way for white directors to signal their tolerance and respect while masking the deadly truth of colonialism.

When a film is so evidently intolerant toward one identity, it tends to be so toward a few others along the way. An African-American man’s sole personality trait is his dislike of Kanye West, a gay subplot feels tacked on for woke points, and women are either shown as exaggeratedly angry or else criticized for their sexuality. Laura Dern’s Grace soon leaves Nels to never return, making this casting choice look particularly odd and thankless, while Viking’s ex (played brilliantly by Julia Jones) is only a surrogate for the audience, observing the ridiculous ego of the evil golden boy instead of becoming her own character. Rookie police officer Kim Dash (Emmy Rossum), meanwhile, may manage to untangle the situation (shades of Fargo) but she can’t even impress her older male colleague Gip (John Doman) because her primary way of obtaining information is to use her sexuality—a reductive and frankly boring screenwriting trope. If we are meant to roll our eyes at Gip, like she does, we end up doing so toward the entire film and its attempts at social critique. Unlike Neeson’s bizarre struggle this week, there’s really nothing to see here.