On Wednesday, FanGraphs released its list of the top prospects in baseball, capping the annual pre-spring-training online rankings rollout that has also swept Baseball America, Baseball Prospectus, MLB Pipeline, ESPN, and The Athletic. Almost all of the lists look the same at the top; ESPN’s Keith Law was the only one of those six sources not to anoint Blue Jays third baseman Vladimir Guerrero Jr. as the sport’s most promising rookie-eligible player, and Law, who preferred Padres shortstop Fernando Tatis Jr., bumped Guerrero by a single slot.

The consensus about the game’s top pitching prospect was even stronger: All six sources ranked Astros righty Forrest Whitley as the best bet among arms, placing him fourth, fifth, or seventh overall. Even more striking than the agreement about Whitley is the scarcity of other pitching prospects toward the top of the lists. FanGraphs’ list includes only one pitcher among its top 13 prospects and three among its top 20, one of whom is a two-way player (the Rays’ Brendan McKay, a left-handed pitcher who also plays first base). The Athletic’s John Sickels put two pitchers in his top 11, while MLB.com and Baseball America put two in their top 12 and Baseball Prospectus and Law put two in their top 13.

In the 1990s, Baseball Prospectus founder Gary Huckabay coined the expression “There’s no such thing as a pitching prospect” (often abbreviated as “TINSTAAPP”) to highlight the attrition rate of young pitchers and the importance of promoting the promising ones quickly so as not to squander whatever period of productivity precedes the almost inevitable onset of injuries. Although Huckabay later referred to the phrase as “an overstatement designed to sell books,” it became a common mantra in sabermetric circles. Now that philosophy seems to be spreading to scouting circles, too. Thanks largely to rising injury rates, changes in pitcher usage, and a heightened awareness of historical prospect-success rates, highly ranked pitching prospects are the sport’s endangered species. In 2019, TINSTAAPP applies to the top of public prospect lists much more than before.

Beginning with 2007 and 2008 studies by Victor Wang, who now serves as the Indians’ pro scouting director, and continuing with widely cited follow-ups from Royals Review, Pirates Prospects, The Point of Pittsburgh, and FanGraphs, public research has unfailingly shown that top-tier hitting prospects outperform top-tier pitching prospects, on average. Although a 2012 Baseball Prospectus study showed that pitching prospects have become a bit more dependable over time, it concluded that “batting prospects still vastly outperform pitching prospects.” In a 2015 BP piece, authors Jeff Quinton and Jeff Long questioned the utility of TINSTAAPP, calling it an “overcorrection,” but they nonetheless acknowledged that “pitching prospects are, unsurprisingly, riskier than hitting prospects.” According to data provided by Baseball-Reference, hitters ranked in the top 10 by Baseball America from 1990-2010 have produced 18.0 WAR for the teams they were with as prospects and 27.4 career WAR, on average, while pitchers ranked in the top 10 over that period averaged only 8.9 WAR and 14.6 WAR, respectively.

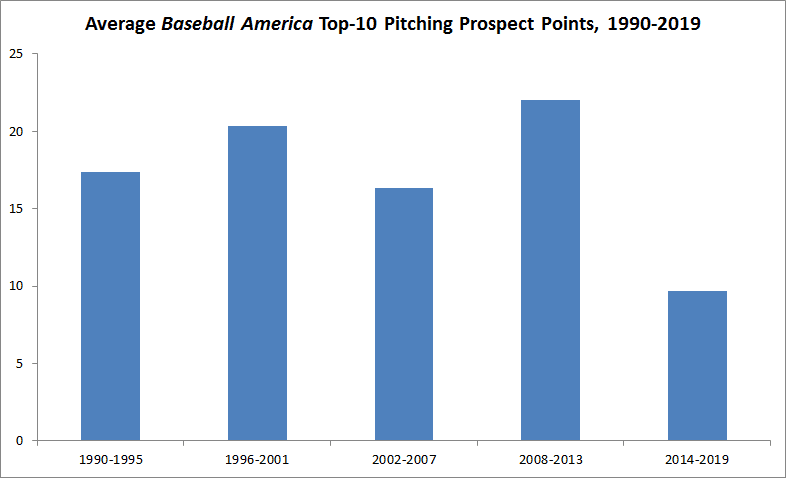

The state of the top of today’s prospect lists, then, is in part a response to the failings of pitching prospects past. Baseball America began publishing its annual lists of baseball’s top 100 prospects in 1990, giving us a 30-season sample. To track the representation of pitchers in the top 10 over time, I assigned points to each slot so that the no. 1 prospect gets 10 points, the no. 2 prospect gets nine points, and so on, down to the no. 10 prospect, who gets one point. Then I added up the point totals for pitchers (or two-way players classified primarily as pitchers) in each year’s top 10 and examined the average during each of the five spans of six years covered by BA’s rankings. The graph below shows that pitchers have gotten much less prominent placement in BA’s top 10s lately than they did in any of the preceding periods.

The positional strengths and weaknesses of prospect lists fluctuate from year to year as some future stars graduate and others replace them in the rankings, so it’s possible that some of this is cyclical. “We could simply be in a down cycle for pitching at the moment, and things could look much different five years from now,” Sickels says. But he also points to the “impact of sabermetric consciousness,” noting that “people are much more aware nowadays of the injury risk that young pitchers face and factor that into analysis more directly than they did 10 years ago.”

There’s almost certainly more to this trend than random rankings turnover. “It’s definitely a conscious decision,” says Baseball America executive editor J.J. Cooper, who’s been at BA since 2002. Cooper continues, “It’s hard to find a top pitching prospect who hasn’t had a serious injury in recent years, and many of them have struggled to find the same stuff and effectiveness post-injury. So more and more, even the best pitching prospect is going to rank behind the best position prospects. … It’s something that hangs over Top 100 Prospects discussions now. Every time we add up how many top pitching prospects have missed a season or more because of a significant injury, it affects how you rank the next group.”

BA’s latest list leads off with Guerrero, who’s about to turn 20; Tatis, who just turned 20; and White Sox outfielder Eloy Jimenez, who turned 22 in November. Each member of that trio has hit well in the high minors and seems like as close to a lock for a long big league career as a prospect can be. “Forrest Whitley is an outstanding pitching prospect, but … no one at Baseball America, and no one I talk to in front offices, is as confident in him [as] they are in those top hitting prospects,” Cooper says. “There’s just too much that can go wrong.” Such is the uncertainty about pitching prospects that BA ranked Rays shortstop Wander Franco just ahead of Whitley, even though Franco hasn’t yet turned 18 or advanced beyond rookie ball.

Cooper says that the last straw for him when it came to highly placed pitching prospects was Dodgers southpaw Julio Urías, who appeared on BA top 100 lists three times, topping out at no. 4 in 2016. Urías made the majors that May at age 19, but he missed most of the 2017 and 2018 seasons after undergoing anterior capsule surgery. The lefty, who returned late last year to pitch out of the bullpen, won’t turn 23 until August, but the shoulder is still a concern. “He was a near-perfect pitching prospect: extremely advanced for his age, excellent stuff, and solid control,” Cooper says. “And the Dodgers had gone far out of their way to make sure he was never over-worked. And he still broke down with a serious injury that will likely affect his ability to meet his very lofty ceiling. Even the riskier top hitting prospects like Yoán Moncada still are likely to have lengthy, productive careers.”

Cooper stresses that he doesn’t subscribe to a literal interpretation of TINSTAAPP. Young pitchers come with wider error bars and bigger bust potential than equivalently talented hitters, but there are pitching prospects. Over the past 20 years, the only pitchers ranked in the top 10 by BA not to make the majors were 6-foot-10 Seattle lefty Ryan Anderson, who ran into injuries and topped out at Triple-A after appearing in the top 10 each year from 1999 to 2001, and another injury-plagued Dodgers southpaw, Greg Miller, who placed eighth on the 2004 list. Jesse Foppert and (thus far) Lucas Giolito are the only other top-10 arms in that span not to produce positive WAR.

Even so, many of the pitching prospects who “made it” didn’t deliver the type of performance that prospect hounds had in mind then they elevated them on their lists. Six of BA’s eight no. 1 or no. 2 prospects from 1990-93 were pitchers, and the best of the bunch turned out to be 1990 no. 1 prospect Steve Avery, who went on to be worth 12.5 Baseball-Reference WAR. The last pitcher to take the top spot on a BA list was Daisuke Matsuzaka in 2007, and the last minor league pitcher to appear in that spot was Josh Beckett in 2002. It would take a rare pitching talent to end that drought, because the rankers have learned from their formerly overexuberant approach. “We do pretty constant self-examination,” Cooper says, adding, “We look at hits and misses. And we try to course correct.”

It’s not that the talents aren’t there; it’s just that they’re all to some degree damaged, and current prospect rankers are less likely to look past the risks and be seduced by the ceilings. Like anyone else, scouts are subject to operant conditioning, and highly ranked pitchers are more likely to lead to negative reinforcement. “It feels like shit when you rank a guy near the top of the list and he gets hurt, and you shy away from doing it again,” says FanGraphs’ Eric Longenhagen. Jim Callis, a longtime BA executive editor who has served as a senior writer for MLB Pipeline since 2013, name-checks several pitchers in the teens, 20s, and 30s on the list who could have merited top-10 consideration if their elbows hadn’t balked.

“Alex Reyes would rank a lot higher if it wasn’t for Tommy John,” Callis says. “Brent Honeywell is up there pretty high. Hunter Greene’s got elbow stuff going on. Even Casey Mize, he didn’t have surgery, but going into last year, he got shut down twice as a sophomore with elbow issues and had a PRP injection, and there were concerns about him. I love Jesus Luzardo, I still do. If he didn’t have Tommy John in his past, and he was even more developed, maybe he hadn’t lost a year, he’d rank higher on the list.” Callis could have kept going: Michael Kopech (no. 18) is currently rehabbing from Tommy John surgery, while Dylan Cease (no. 21) is a TJS survivor and Mike Soroka (no. 24) and Sixto Sanchez (no. 27) missed much of last season with shoulder and elbow injuries, respectively.

The other problem with pitching prospects is that even if they make it through the injury gauntlet, changes in MLB pitcher usage have limited the extent to which any individual pitcher can contribute to a team. Although pitching staffs still collectively amass as many innings as ever, that work tends to be scattered across many more arms. Contemporary position players spend roughly as much time at the plate and in the field as they used to, but relievers are rarely top-10 material, and starting pitchers aren’t on the mound as much as they once were. “Twenty years ago, you’re trying to develop that 250-inning pitcher,” Callis says. “Those guys just don’t exist anymore, and so maybe there’s some cognizance of, ‘Hey, even the best starting pitchers, maybe you’re only getting 180 innings out of them,’ so you’re gonna lean toward hitters. … Unless the starter is really dominant, I’d rather have the position player.”

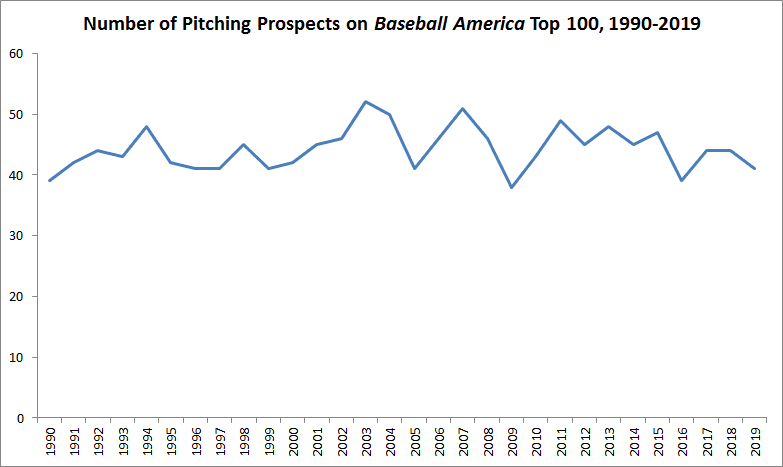

Callis cautions that it’s possible to take a hitter-first philosophy too far. “If you look at it that way and say, ‘Oh, we’re only gonna bet on hitters,’ well, then you’re never going to have any pitchers,” he says. Teams still need pitching, and many prominent major league pitchers were once pitching prospects, TINSTAAPP be damned. Notably, the number of pitching prospects appearing at any position in BA’s top 100 isn’t abnormally low; this year’s list features 41 pitchers, and the last six lists have featured an average of 43.3 pitchers per season, higher than the figures from 1990-95 or 1996-2001. Only the distribution of those prospects has changed, with fewer pitchers clustered in the rarified air reserved for reputed no-doubters.

Reputable rankers consult closely with scouts and front-office officials as they assemble their lists, so the shift away from top-10 pitchers on public lists mirrors a similar movement inside the game. “One of the things I have gotten more often in recent years is front-office officials discussing how the injury risk of pitchers affects how they line up prospects,” Cooper says. “We try to reflect what we are hearing from industry sources.” FanGraphs’ Kiley McDaniel, who returned to public prospect analysis in December 2017 after a stint as a Braves baseball operations staffer and scout, says, “I think teams figured this stuff out well before the [public] list people. Or the progressive ones did, at least.”

Progressive teams have also grown more adept at making low-profile pitching prospects into major league material. In an era of data-driven player development, “You can create a pitching prospect,” Callis says, noting that the advent of sensitive tracking technology, high-speed cameras, and sophisticated velocity programs has made it more feasible for pitchers to make sudden strides. And some of those strides are almost imperceptible to public prospect rankers. “Trackman/Statcast data on hitters (exit velo/launch angle) is stuff that scouts can see much more easily, and we can approximate without having the data,” McDaniel says. “Whereas fastball rise or spin rate-based deception are really hard to peg even from video.”

Barring rule changes or medical breakthroughs, the game’s emphasis on velocity, the resulting increase in injury risk, and increasingly short hooks for starters could continue to put pitching prospects in a subordinate role in the rankings. Rather than debuting as unpolished products and scuffling for a few years before reaching their peaks, modern position players are producing from the get-go, and young hitters on the whole are enjoying historic success. That leaves less space for pitchers at the top of prospect lists.

Although an influx of international talent—including Guerrero, Tatis, and Jimenez—has bolstered baseball’s prospect crop, Callis observes that “international guys who are really, really good, it seems like more of them are hitters than pitchers.” Nor does it look like any elite pitching-prospect reinforcements are arriving on the domestic amateur market. “A lot will change between now and June, but it’s not a very good pitching draft,” Callis says, adding, “I don’t even think there’s a college pitcher right now who would go in the top five or six picks of the draft, which is really unusual. All the top college arms, there’s some good ones, but there’s a pretty obvious red flag with most of them.” Mize, whom the Tigers took out of Auburn with the no. 1 overall draft pick last year, is 17th on the current MLB Pipeline list, and Callis says “there’s no pitcher in this year’s draft who can come close to that.”

In an era of almost interchangeable arms, prospect lists are the latest arena in which the stats and the scouts are increasingly saying the same thing. Fortunately, that philosophy happens to have a handy acronym. TINSTAAPP still isn’t technically true, but among baseball’s blue-chippers, the decades-old sabermetric credo makes more sense every spring.

Thanks to Dan Hirsch of Baseball-Reference for research assistance.