During the early-morning hours of January 6, 1999, NBPA executive director Billy Hunter, chief outside counsel Jeffrey Kessler, and NPBA general counsel Jim Quinn walked up Fifth Avenue reflecting on what they’d accomplished. Collectively, they’d helped save the 1998-99 NBA season. But none of them knew the shape that season would take. The answer soon followed.

The 1999 NBA campaign was unlike any other: free-agent signings and a 12-day training camp beginning simultaneously on January 21, leading up to opening night on February 5. The regular season consisted of 50 games in 90 nights, a grueling slog in an era before DNP-REST. Back-to-backs were the norm. Three games in three nights were common.

“You know how guys say that the season is a marathon?” veteran guard Terry Porter says. “Well, that year it was a sprint. It was a full-out sprint.”

The 1998-99 season was infamous for its bad brand of basketball. Players were out of shape, offenses sputtered, and injuries mounted. And though the season ended with the arrival of a new dynasty, the league’s reputation had suffered. An average of 16 million viewers watched the San Antonio Spurs defeat the New York Knicks in the 1999 NBA Finals, down 40 percent from the previous season. It was the lowest-rated Finals since 1981.

But before a game was even played, a collective bargaining agreement needed to be ratified.

Though a hard salary cap wasn’t part of the 1999 CBA, the owners gained three significant cost controls from the union: a luxury tax for high-spending teams, an escrow tax to be introduced in the 2001-02 season, and a cap on individual player salaries known as “the max salary.” In return, the players received exceptions that benefited the mid-and-lower-level players and ensured the retention of the soft cap, guaranteed contracts, and the Larry Bird exception. There was no fixed number regarding the players’ share of basketball-related income for the first three years of the CBA. For years 4 through 6 of the deal the players received 55 percent of BRI, and the figure jumped to 57 percent in Year 7. It was a moral victory for the union. “[It proved that] you can’t run over the players,” then–New Jersey Nets guard Kendall Gill says. “That’s the one thing I got out of [the lockout]. The players stood strong for a good amount of time.”

“I think there was a perception that NBA players would never miss a paycheck, and that perception was shattered,” then–NBPA spokesperson Dan Wasserman says. “There was a perception: ‘Oh, they’ll fold, they’ll never miss a paycheck.’ They missed a lot of paychecks.”

Jeffrey Kessler (chief outside counsel for the union): We improved minimum salaries. We improved a lot of the exemptions for the middle class.

Ron Klempner (NBPA lawyer): We also got a huge benefits package. Each team put in a million dollars, and that created our 401(k) and our health reimbursement accounts. Starting from the 2000-01 season and to this day, every player has health reimbursement accounts in the six figures.

Aaron McKie (Philadelphia 76ers guard): I think 50 percent of the guys were excited to go play ball and 50 percent just didn’t like the deal.

Terry Porter (Miami Heat guard): I was at the end of my years, and that veteran minimum made my world a little easier.

Will Perdue (San Antonio Spurs center): I thought it favored the owners too much.

I think 50 percent of the guys were excited to go play ball and 50 percent just didn’t like the deal.Aaron McKie, Philadelphia 76ers guard

Juwan Howard (Washington Wizards forward): It wasn’t a deal that we were happy with, but we had to sacrifice in ways to work it out.

Antonio Davis (Indiana Pacers forward): We must have done something right for numbers to be where they are today.

Kessler: The final deal we ended up with in ’99, even though it involved a number of significant changes in the system, was a vastly better deal for the players than what they were offering on July 1. It took a long time to get from July 1 to a deal that the players were willing to accept.

Billy Hunter (NBPA executive director, 1996–2013): All of the owners’ proposals were off the chain. They were cutthroat offers. I told Stern, “I’m not going to fall on the sword for the owners.”

Dan Wasserman (NBPA spokesman): Their proposals were just beyond draconian. It was so much worse than what we ended up with.

David Falk (agent): It was basically the same deal. They didn’t get one significant concession at all.

Klempner: First of all, [the owners’ July offer] was a hard cap beginning in Year 3. There would be no Larry Bird exception. … When they finally moved, they moved backward. They gave us a list of horribles in September 1998 that we called death by a hundred needles.

Falk: If Billy had walked in in June and said, “Don’t lock us out—if you give us the following three things … you have a deal,” they would have made the deal. Do you think the lockout improved Billy’s bargaining power? Whether or not the league was offering it at that time doesn’t mean they couldn’t have gotten it. Obviously, if they got it in January after the players were bleeding, they could have gotten it in May. Isn’t that logical?

Kessler: The max salary was something players knew would be a double-edged sword.

Falk: I signed [Stephon] Marbury after his second year. He came to me and asked to sign with me. Then, they put the max in. He couldn’t deal with the fact that he wasn’t going to make as much as Kevin Garnett, because he thought he was better than Garnett; he’s probably the only person in the world who thought that.

Jim Quinn (former NBPA general counsel): Of course it turned out that it ultimately benefited the players because you had situations where players were saying, “If he gets the max, I should get the max.” It became a lightning rod that had the tendency to increase players’ salaries.

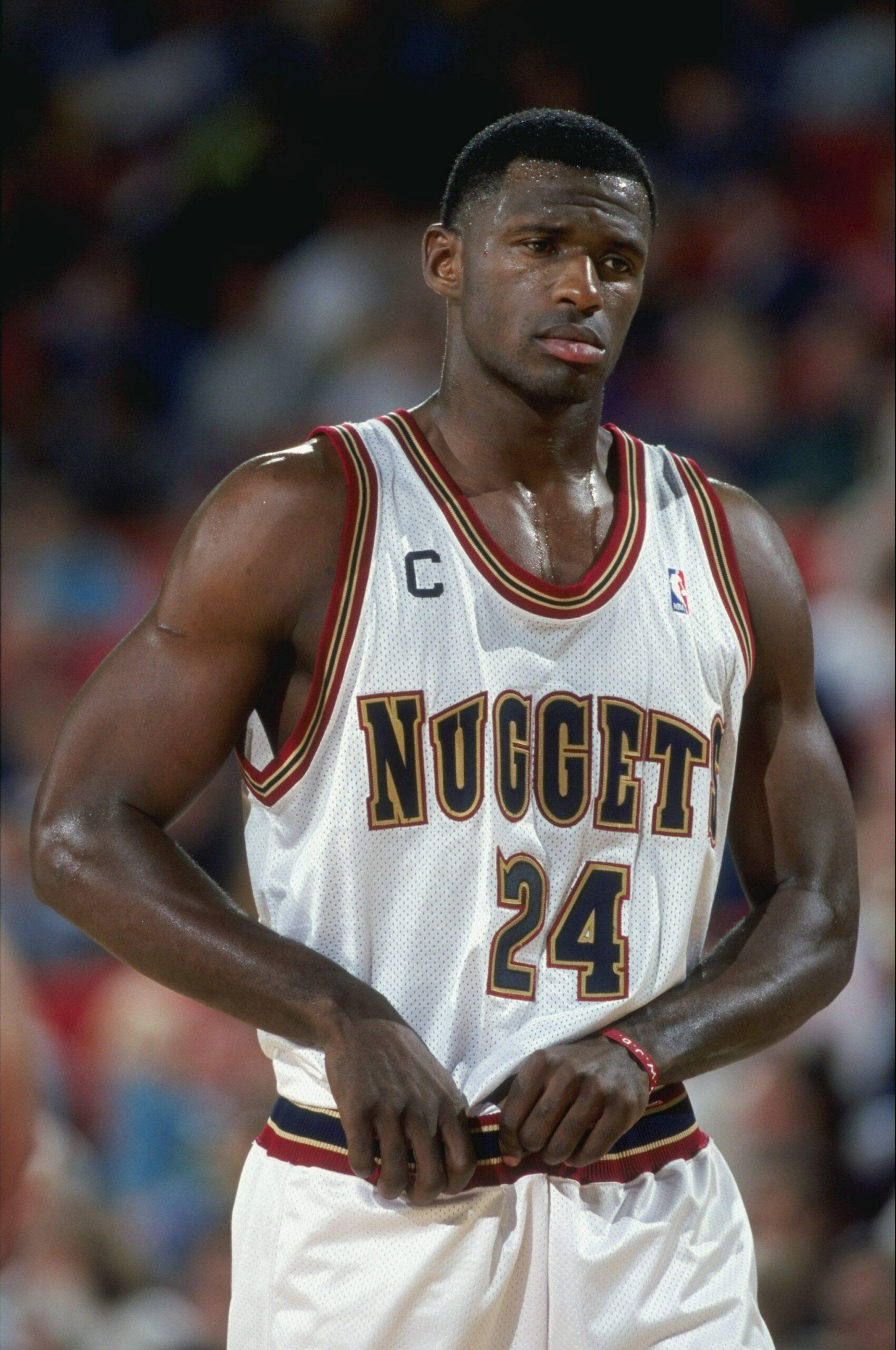

Nick Van Exel (Denver Nuggets guard): Man, I didn’t care about the max contract. I just wanted a good deal, and I thought the deal that Dan Issel and Denver offered me was great coming off making $1.9 million. [Van Exel signed a five-year, $50.5 million contract in summer 1999.] I was good with it. I thought I was making a shitload of money.

I signed [Stephon] Marbury after his second year. He came to me and asked to sign with me. Then, they put the max in. He couldn’t deal with the fact that he wasn’t going to make as much as Kevin Garnett, because he thought he was better than Garnett; he’s probably the only person in the world who thought that.David Falk, agent

Bob Whitsitt (Portland Trail Blazers general manager and team president): I was always against the max salary. Now the players, with their win-lose mentality, had the mind-set that, “If you don’t max me, you’re disrespecting me.”

Klempner: It set a bar for players who otherwise wouldn’t be at that level.

Whitsitt: I like Damon Stoudamire. I like him as a person. I liked him as a player. But his deal was up and he was not coming to training camp because we hadn’t signed him. My owner, Paul Allen, called me and said, “Give him the max.” I say, “It’s seven years, $86 million.” “Yes, give him the max. Give it to him now. I want to pay him $86 million because I want him there on the first day of camp.” I’m like, “Are you kidding me?” I like Damon, but that’s not anywhere near where I would have valued Damon on the pay scale. I signed him that day for $80 million. I chipped off $6 million. I couldn’t help myself.

Damon Stoudamire (Portland Trail Blazers guard): It wasn’t going to make or break me, man. $80 million or $86 million, it’s all the same. We all in the same tax bracket. We all gonna spend it the same way.

On January 6, about 200 NBA players converged at the GM Building in midtown Manhattan to approve the CBA, which had been agreed upon just hours prior. Earlier in the week, rumors had spread that Shaquille O’Neal and Hakeem Olajuwon were plotting to overthrow union leadership if the negotiating committee didn’t put the owners’ most recent proposal up for a vote. That was no longer necessary. The union had a deal it considered palatable. But frustration had been building for six months.

Keith Glass (agent): What a circus. That day was a circus.

Kessler: The scramble that morning was to write everything up, brief the [negotiating] committee … and then they had to make a decision on whether they would recommend it to the players. There were a lot of moving parts that morning.

Perdue: This is where the quality of your agent comes in. Arn Tellem had us all in the same hotel and we had breakfast together the morning of the vote. Arn had a copy of the new agreement, and we went over it page by page and line by line. So we had an understanding of what was going on when we walked in for the official vote later that afternoon.

That’s where Charles slapped the shit out of Charles.Billy Hunter, NBPA executive director

Jayson Williams (New Jersey Nets center): What we did was get Olajuwon, Charles Oakley, Anthony Mason—I was trying to get some of the baddest jokers I know—and we were just going to go down where they had the vote and raise hell. We were going down there to demand to get the vote and make sure no one was intimidated. When I called the night before, I said, “Hey, man, dress professional tomorrow. Suits. Don’t come in looking like a bunch of wealthy superstars.” I remember Anthony Mason coming in with a black fur coat that went from his chin to his feet. I said, “Mase, what are you doing?” He says, “This is a bad-ass coat, ain’t it, Jay?” I said, “A fur coat and a fur hat?” “That’s not it,” he goes. He turns around and the number 14 was on the back.

Hunter: That’s where Charles slapped the shit out of Charles.

Davis: Oh man, I knew that was going to come up. The one thing I didn’t want to happen was for us to get distracted from why we were there. We were all just standing in a hallway. Charles Oakley then walks in.

Chris Childs (New York Knicks guard): Oak spots Barkley and walks toward him.

George McCloud (Phoenix Suns forward): He made a beeline to Barkley.

Childs: Barkley puts his hand out like to shake his hand and Oak goes off and slaps him.

Hunter: He slapped the shit out of Charles. KA-POW! Yeah, I saw it. I couldn’t believe it. I said, “Shit, what is going on?”

McCloud: Oakley wouldn’t let you grab him, so he was swinging at everyone who tried.

Davis: I’m grabbing Oak and telling him, “Hey, I understand, bro, but this is not the place. Not here! Not now! Not here! Not now!” I was begging him. I remember grabbing him and he was like, “Let me go. Let me go.” I’m like, “Please, man. Not here, not now.” He was like, “All right, all right, but you know.” I was like, “Oh my goodness, this could get really ugly really fast.”

Hunter: Barkley then fled from the room. We never saw him again, not that night. [Barkley did not respond to requests for an interview.]

Childs: That slap was so loud it echoed from person to person all the way around the room. It was that loud. I laughed. I thought it was the funniest thing because Oak said he was going to do it.

Glen Grunwald (Toronto Raptors general manager): Oak was supposed to get a balloon payment of about $7-8 million that season from his time in New York. Then we missed half the season and he didn’t get half his balloon payment. I felt he kind of got screwed on that.

Davis: It was less about [the lockout] and more about their history.

Childs: Some stuff was said beforehand. It came up in an interview about what kind of player Oakley was, how he hustled and played hard. Barkley said, “You know when they say someone hustles and plays hard? That means he can’t really play.” I can’t remember the exact words. Oak got wind of it and said, “When I get to New York, I’m going to go up to him and slap him. I’m not going to punch him. I’m going to treat him like a ta-da-da-da-da.” We were all sitting there waiting. I knew it was going to happen because I know Oak. He slapped a few people during my time in New York and Toronto. Several. I was there. I witnessed it.

That slap was so loud it echoed from person to person all the way around the room. It was that loud. I laughed. I thought it was the funniest thing because Oak said he was going to do it.Chris Childs, New York Knicks guard

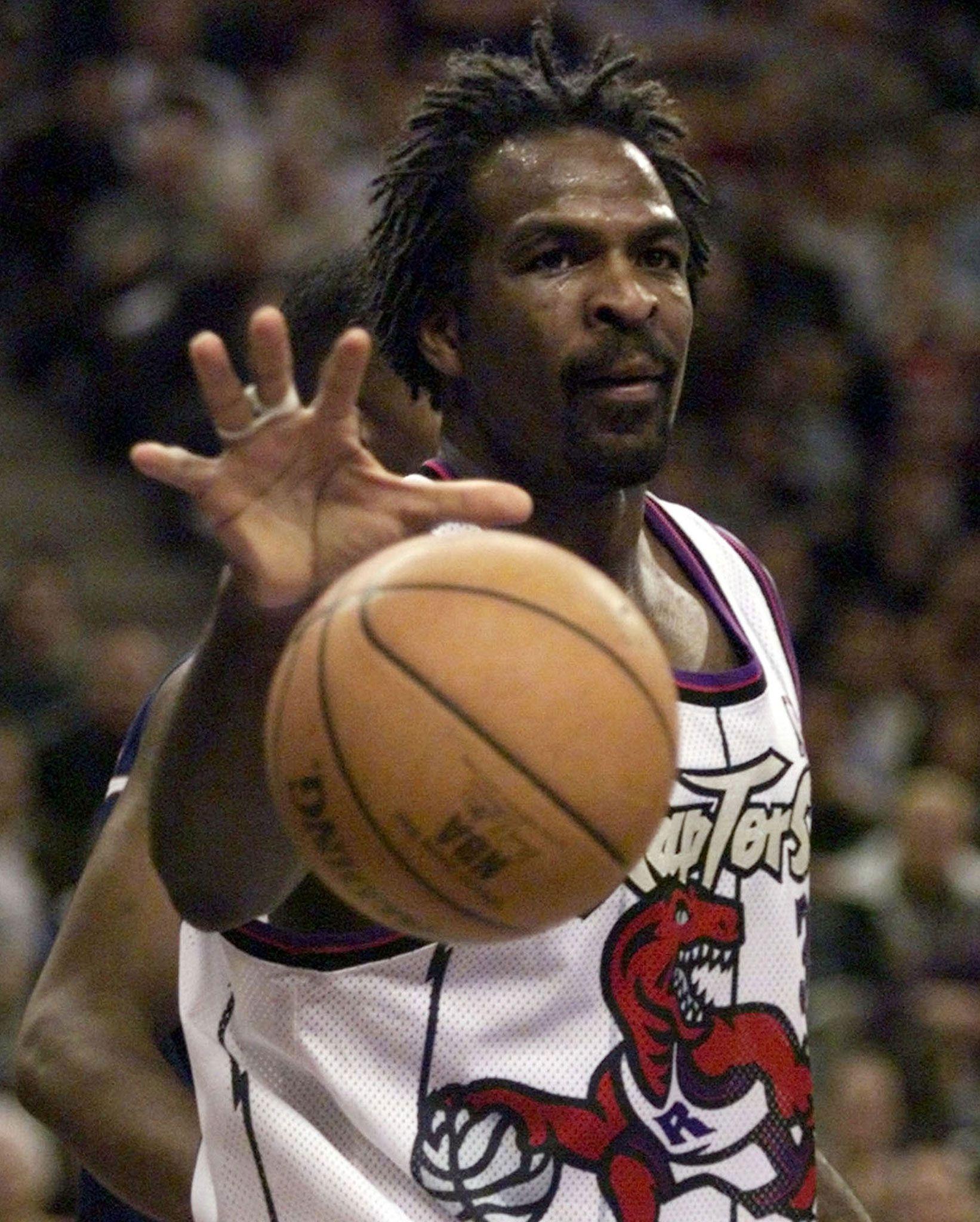

Charles Oakley (Toronto Raptors power forward): Remember the game they had in Atlantic City? They had like a little workout? … Barkley had said something. I said, “Barkley is always saying something.” I said, “Next time I hear him say anything about anybody who named Charles, I’m gonna smack him.” So the lockout came and he was there and I seen him and I told Chris Mills and I told Derrick Coleman and Mase [Anthony Mason], “I’m gonna go smack him because I told him when I see him, I’m gonna smack him …” I went over to him and I said, “Hey, what I tell you about talking, saying something about my name? Talking, you know, about ‘Charles.’ I don’t know who you were talking about, but I heard ‘Charles.’” And I just smacked him. [From The Bill Simmons Podcast, June 2018; Oakley declined an interview request for this story.]

Davis: After it was broken up, some guys were feeding off that energy. You could see a swirl that was happening and that this—voting for this deal—was getting away from us. I was thinking, “There is no way we can put this off. We have to vote.” It was awful. But I couldn’t imagine us getting through that day without one fight.

Leonard Armato (agent): Stern came in and announced there was a done deal.

Perdue: Stern made this speech and then Charles Oakley stood up and went off on him. It got kind of heated. And then they passed this thing out, had us vote yes or no, and that was it.

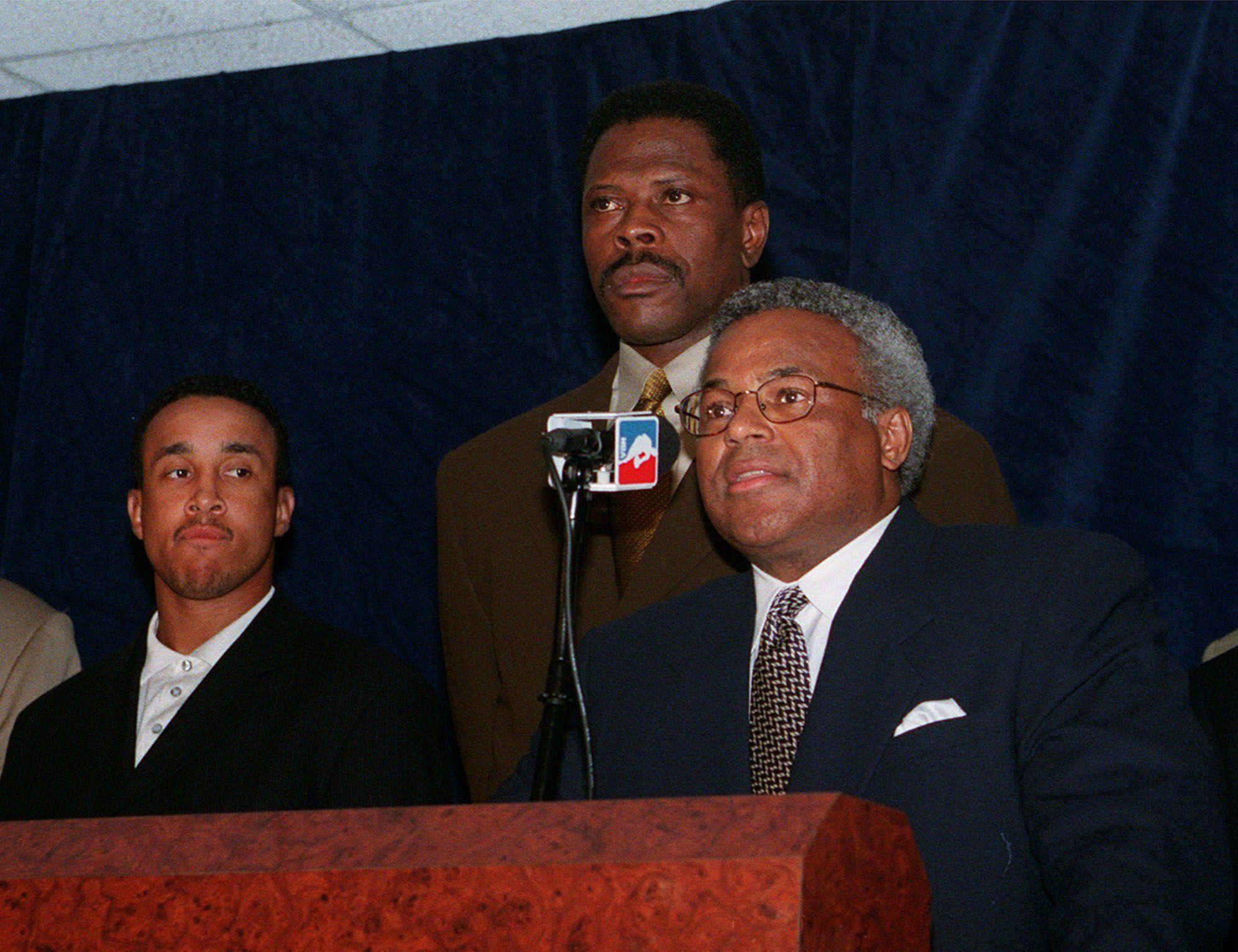

The players approved the deal with a 179-5 vote.

David Stern (NBA commissioner): All labor disputes come to an end. … We are once again an NBA family. … Patrick and Billy are among the most gentlemanly tough guys I’ve ever come across. I want to thank them for the courtesies they extended me while at the same time beating the hell out of me. You guys will drive us to be the best league in the world. We can’t do it without you and you can’t do it without us. [From his speech to the players after the deal was ratified on January 6, 1999.]

Glass: Once the deal was ratified, I went up to Patrick Ewing and thanked him for my players. I gained a lot of respect for Patrick and I felt like he put his foot down, drew a line in the sand and did not cross it. He took a lot of crap—personal crap—that was way out of line and that I did think was racial at the time. He never blinked.

Chris Dudley (New York Knicks center): Patrick’s motives and example were beyond reproach. He did things that weren’t in his personal best interest.

Hunter: I was always concerned about my relationship with Patrick, because I really liked him and his character, his strength, commitment, and dedication. I was concerned that I had let him down, in view of going to Armato’s office and all of that. [The Georgetown media relations department did not respond to an interview request for Patrick Ewing.]

Kessler: He is one of the most underappreciated union leaders in the various sports. He was completely dedicated.

Hunter: Patrick was one hell of a [union president]. He was committed all the way, and I suspect that’s why he doesn’t have a head-coaching job today in the NBA.

Patrick Ewing: I did my job. I did everything the guys asked me to do. I led the best way I could. I was strong when I needed to be strong. The deal is done, and now it’s time to get back to work. [Said to reporters on January 6, 1999.]

An agreement was reached during the early-morning hours of January 6 and the players approved it the next day, but the deal still wasn’t done. “Even after you resolve the principal deal points, writing up the CBA is a bear because the devil is in the details,” Jeffrey Kessler says. “They didn’t want a dispute like in 1996, so we ended up working like 20 hours a day for 10 days to negotiate every last part of the CBA and get it fully in writing. They wanted the whole deal down.”

The longest lockout in NBA history was lifted on January 20, 1999, and the league was open for business again. But to ensure that the NBA Finals wouldn’t stretch into July, training camps and free agency started simultaneously. “It was a game of musical chairs on steroids,” agent Mark Bartelstein says, “and we had to grab those chairs before they were gone.”

Big names such as Scottie Pippen and Latrell Sprewell were on the move, but the strangest saga of the signing period involved a 24-year-old power forward from Quitman, Mississippi (current population about 2,500).

McCloud: One time during the [1997-98] season [Phoenix Suns owner] Jerry Colangelo called me and asked me to reach out to Antonio McDyess so they could talk. Dice and I were real tight. That’s still my dude. But he stopped talking to everybody. He wasn’t returning Jerry’s calls. I call Antonio. I’m like, “Man what the hell is wrong with you? You do know that’s the goddamn owner calling you and you’re not calling him back.” He goes, “Man, they had something in the paper about trading me.” I said, “Dice, look here, if I was Colangelo and I was calling you and you weren’t returning my calls, I would look for options also. You’re not calling the owner back.” [Attempts to reach McDyess were unsuccessful.]

Dan Issel (Denver Nuggets general manager): Antonio was just a great kid and was really the crown jewel of what we were trying to do that year. We had Nick Van Exel. Nick and Antonio had become really good friends. Nick knew of our interest and that we wanted Antonio to come back to Denver.

Van Exel: Dan was like, “What’s our chances? How can we get him here? How can we make him really happy? We really want him back.” I just did whatever I could. We had stayed around the corner from each other in Houston during the lockout, and I would leave Krispy Kreme doughnuts on Antonio’s doorstep every day because I knew he loved sweets. I’d never been through a summer like that where I was begging someone to come play with me. I was trying to convince him that we’re going to do this as a team, and that me and him are going to be like Stockton and Malone and all kind of nonsense.

Issel: We might have cheated a little bit. I did have conversations with Nick prior to the lockout telling him that was who we wanted to sign and that’s who we wanted him to help us get.

Van Exel: When it came time to be closer to the season it got heated. We had gotten him to Denver, then some Phoenix guys flew in, George McCloud, [Jason] Kidd, and we’re all in the same hotel on different floors. It was the wildest thing ever.

Issel: That was the longest day of my life. Antonio was having second thoughts.

McCloud: We were in Phoenix and J-Kidd and Rex Chapman knocked on my door at about 4 in the morning. I’m like, “Man, what you guys want?” “Come on, we’re going to Denver. We got to talk to Dice. Jerry gave us the plane.” We didn’t bring any clothes. We get to the hotel in Denver. We see Nick Van Exel—I’m cool with Nick because we played half a season together on the Lakers—and when he sees us he put his head on the counter. Dice’s agent, Tony Dutt, was right there. He’s looking at us and he knows what we’re trying to do. I was calling Dice and he wasn’t answering. He was at the Colorado Avalanche game.

Issel: I remember he went down to the Avalanche locker room and Patrick Roy gave him an autographed stick. A delegation from Phoenix including my good friend Rex Chapman [arrived]. … But since they didn’t have tickets to the Avalanche game, security didn’t let them in the building.

McCloud: We pulled the limo around in the back. Now it’s a blizzard. A blizzard. We don’t have any winter clothes. We just left Phoenix where it was 80 degrees. All of a sudden they rolled up the big garage door and as soon as they let it up Rex and Jason tried to walk in. We are now trying to hurry up and get inside.

Issel: Hey, they didn’t have tickets to the game. No one without a ticket can get in. [Laughs.] Antonio is a very kind-hearted person and I think through the whole process he didn’t want to let anyone down. But we knew that if he got on that plane and went back to Phoenix we’d never see him again.

Van Exel: Eventually we ended up winning and he came to Denver.

Issel: The biggest ally we had was Nick, and [he, Mike D’Antoni, and John Lucas] drove through a snowstorm from training camp in Colorado Springs to get there that night.

It was a strange training camp even for players who didn’t drive through a blizzard to recruit free agents. Coaches adjusted their practice schedules; rookies lagged; new players—including a famous rapper—shuttled in and out of camp; and everyone worked on their conditioning.

Grunwald: Training camp started and we didn’t have a full roster in.

Anfernee Hardaway (Orlando Magic guard): We were happy to be back, but it was still kind of weird going back in January.

Kevin Willis (Toronto Raptors center): Once you’ve gone through Pat Riley’s training camps, everything else is gravy.

Lenny Currier (Philadelphia 76ers head athletic trainer): Camp was a day-to-day grind. We had some two-a-days. Larry Brown absolutely loved practicing. He loves being in the gym, loves practice, and loves to teach.

I wasn’t in great shape. I wouldn’t say I was in basketball shape.Antoine Walker, Boston Celtics forward

Mike Dunleavy (Portland Trail Blazers head coach): I would do two-a-day, two-a-day, day off, two-a-day, two-a-day, day off, and then one-a-days. Obviously, conditioning is going to be a part of it. I thought our guys were pretty well conditioned, but we still tried to top off the gas tank to stress them to be ready.

Whitsitt: You could look around the league and could point to a handful of guys and go, “My God, how much weight could you gain in three months?”

Williams: I remember that nobody was in good shape. I was not in the tip-top shape that I should have been in.

Antoine Walker (Boston Celtics forward): I wasn’t in great shape. I wouldn’t say I was in basketball shape.

Whitsitt: Even the guys in good condition, there’s good condition and then there is NBA game shape.

Perdue: I wouldn’t say we were at 100 percent. I’d say we were at 80 percent and that put us ahead of 100 percent of everybody else.

B.J. Armstrong (Charlotte Hornets guard): There was no time for the teams to get in shape. There was no time to prepare.

Dunleavy: You were in scramble mode. How many new guys do we have? How many guys are back and know our stuff? Two weeks is not enough time to get everything you need to get in.

Armstrong: It was one of my favorite training camps because of Master P. [Percy Miller, the rapper/mogul known as Master P, was a nonroster invitee to Charlotte Hornets training camp.] He was awesome. He showed up to practice every day and worked his butt off. He wasn’t trying to be the entertainer. He was dedicated as a player, and he was a good player—played hard, wasn’t afraid, and could hit an open shot. When they played his songs in warm-ups during the games, the response of the people was incredible. I remember them chanting for him to get in the game. He brought an audience. I don’t know if we should’ve been selling out games in the preseason.

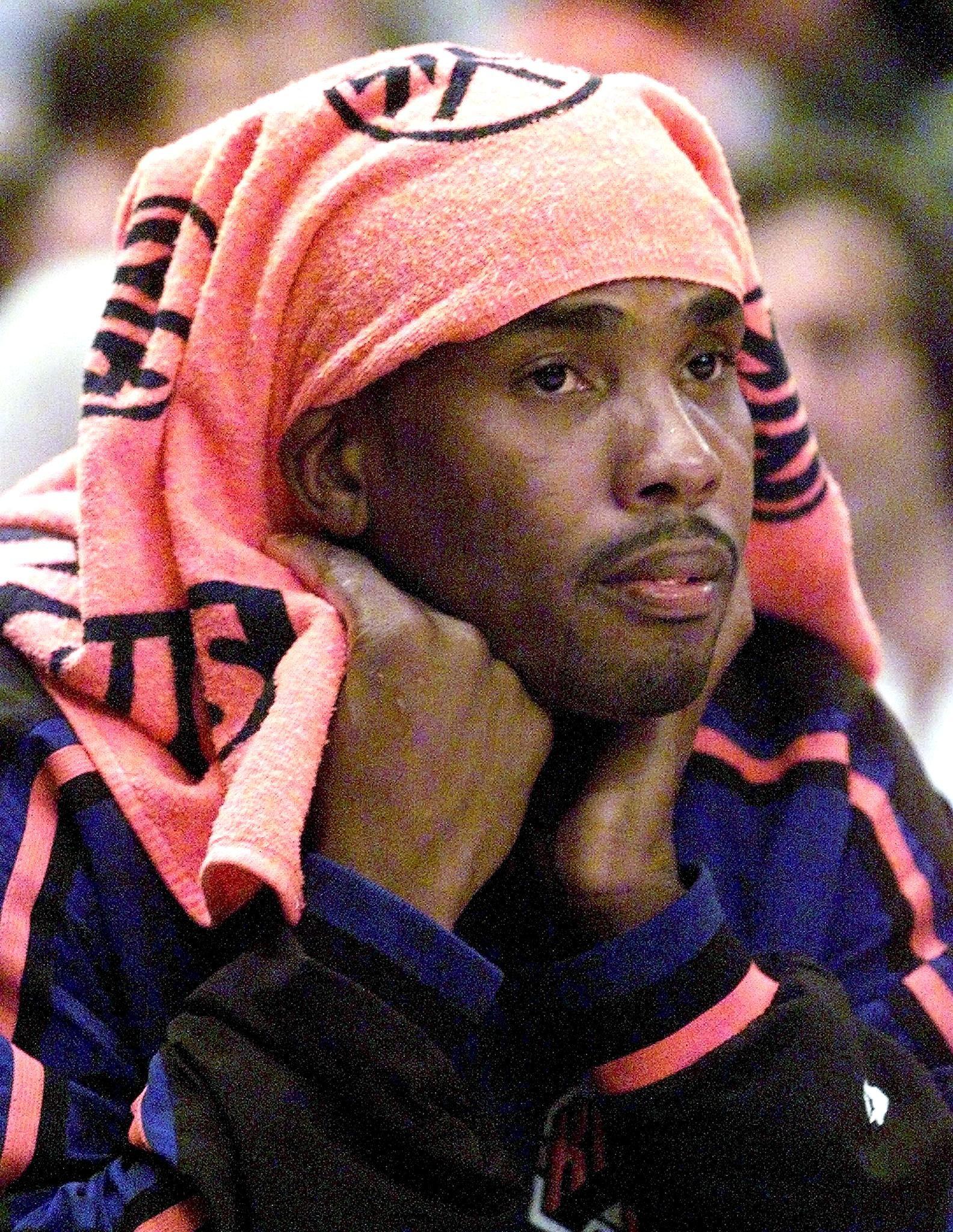

Vince Carter (Toronto Raptors guard): When you go through a training camp, you go through however many weeks of training camp and then eight preseason games, so you sort of get a feel for it. This was so different. It was my first training camp and there was so much information thrown at you. We were basically thrown into the fire.

McKie: It was a bad brand of basketball after that—guys were out of shape—but we were excited to be doing what we do best, and that’s play basketball.

Williams: Usually when you step into camp, guys are like, “Let’s get it done. Let’s see who’s in shape. Let’s see who was working.” Instead, it was like, “All right, guys, we got to make this shit work.” We all came in trying to make shit shine and no matter how much you polish shit, it ain’t gonna shine, right?

When Michael Jordan announced his retirement from the NBA on January 13, 1999, the Chicago Bulls were already in the process of being dismantled, as Iowa State head coach Tim Floyd had replaced Phil Jackson over the summer, and free agents Scottie Pippen and Dennis Rodman were not expected to return. Management had stripped the three-time defending champs down to a rebuilding project.

A slew of mediocre teams were now contenders, but first they had to survive 50 games in 90 nights. As expected, the back-to-back-to-backs took a toll on the players. “It’s always been remarkable to me that we were still able to put a team out there every night,” Lenny Currier says. The basketball was also unwatchable at times, with scoring down four points per game from the previous season—teams averaged 91.6 points, the lowest total in the shot-clock era.

Hardaway: A lot of teams thought they had an opportunity to win a championship.

Davis: We knew it was our year, and we were preparing as if it were our year.

Adam Keefe (Utah Jazz center): The feeling was our team is here, we’re intact, we’re good, we’re going to have a really good shot at this. We felt we were there before [Jordan retired].

Childs: I was pissed. To be the best you have to beat the best. I wanted to play him. I wanted a shot at the champ. I eventually got it, but not on the basketball court, on the golf course.

Porter: People knew the journey would be easier because you didn’t have to go through Chicago.

Whitsitt: I saw a lot of teams that I didn’t think were ready. A lot of teams—and this goes for management, too—went on pretty extended vacations.

Michael Finley (Dallas Mavericks guard): To go from a season with 82 games to 50 games in three months, everyone was out of whack. I don’t think people got into a great groove that year.

Kendall Gill (New Jersey Nets guard): No one had training camp. You didn’t have a chance to get your rhythm. Guys didn’t have their timing and the whole game suffers.

Sean Elliott (San Antonio Spurs forward): The basketball wasn’t good early on.

Dunleavy: If we had back-to-back games, I’d give them the next day off. Very rarely once you get into the season can you have practices with really full contact because you’re nursing injuries and want to make sure guys have their legs for games.

Antonio Daniels (San Antonio Spurs guard): I remember if David Robinson walked in with his San Antonio Express-News, he was not practicing. If he walked in with his watch on, he was not practicing. This is when David’s back started messing with him. There were so many days where we came into practice and the guys playing 30 minutes a night wouldn’t practice and we would play three-on-three.

Currier: When we played three nights in a row, on that third night the final score was, like, 76-69. The fatigue, most of all, affects shooting. Shooting is precise. If you are fatigued in your arms and upper body, the shot is not going to fall. Then the legs go, and if the legs are tired they can’t elevate.

Childs: My legs were dead. I remember where we were on the road and we just had a back-to-back. Usually we get into town and go to dinner. I didn’t go. I just got ice, put it in the tub, ordered room service, and sat in the tub for an hour.

Finley: [A back-to-back-to-back] felt like running in sand.

Porter: It was just grueling. I was an older guy and my body didn’t recover quickly.

Currier: At that time, our recovery process was more hot and cold whirlpools. We all had the plunge tanks whether they were in the floor or the old stainless steel ones. You just try to flush the body of its lactic acid and muscle soreness. The recovery really was Gatorade and water.

Carter: Shoot, I don’t even know if we had foam rollers. You just had the stick that’s like a foam roller that you’d rub on your thighs.

Wally Blase (Chicago Bulls assistant athletic trainer): We know now that recovery is just as important as training. There is so much care given to what a guy does when he comes off the court now and how quickly they get in the cold tubs or recovery boots. Even tights. No one was wearing compression tights on a plane back then.

Williams: I think what kills you is the travel. It was the getting into buses and staying on runways in the middle of February just trying to get into a city. And it was February so automatically there was bad weather in the Northeast. Then you had coaches trying to come in like this was a regular season and sticking to their philosophies and not changing. Our bodies weren’t prepared to start at this time. It takes a while to get into [the season].

Armstrong: There was no way you could play 50 games in 90 days. There was no way you could do it physically.

Blase: You’d get more patellar tendonitis, just inflamed, like their knees and ankles were sore from overuse.

Issel: Twelve games into the season Raef LaFrentz tore his knee and had season-ending surgery. I always wondered if the short time we had to prepare for that season … [had] any effect on that happening.

Jim McIlvaine (New Jersey Nets center): Jayson Williams’s thumb turned to mush. It was heavily wrapped all season. I played 22 games with a torn-up shoulder. It was like, “At what point do you shut it down and get surgery?” That was the season where I started using anti-inflammatories, which I had always been reluctant to do. It always seemed like a bad thing. I always wanted to know how much pain my body was in and not mask it and potentially make it worse.

Williams: To this day, I think I wouldn’t have gotten injured if the season wasn’t so chaotic. It was the last time I played NBA basketball.

When Jayson Williams suffered his career-ending leg injury 30 games into the 1998-99 season, the New Jersey Nets were already the league’s most disappointing team. A trendy pick in the East, the Nets had it all: a beloved homegrown big man (Williams), a potential franchise player (Keith Van Horn), a versatile swingman (Kendall Gill), a sharpshooter (Kerry Kittles), a playmaker (Sam Cassell), and an innovative coach (John Calipari). “Generation Nets: Champs by 2001. Count on it,” read the cover of the April 1998 SLAM magazine featuring the Nets’ starting five.

The Nets lived up to the hype at first, losing a tough first-round series to the Chicago Bulls in the first round of the 1998 playoffs. But they fell apart during the lockout-shortened season, their opening-night 111-106 loss to the Atlanta Hawks at the Georgia Dome an omen of things to come. With six minutes and 53 seconds remaining in the fourth quarter, Dikembe Mutombo elbowed Williams, breaking his nose and triggering a fight between Kendall Gill and Steve Smith; it was later rumored that Mutombo targeted the Nets center due to Williams’s antics during the lockout.

From there it went downhill, with Calipari being fired after a 3-17 start and the team trading Cassell, their popular point guard, for Stephon Marbury. The Nets would finish at 16-34 and Williams, who had signed a max six-year, $86 million contract after the lockout, never played another NBA game after breaking his leg on April 1.

Gill: We thought it was intentional because Mutombo broke someone’s nose [Cleveland Cavaliers center Vitaly Potapenko] the night before.

Williams: Are you crazy? If you think I would let Dikembe Mutombo or anyone in this league let alone a Georgetown guy break my nose and then them getting on the bus without their nose being broke and their jaw, no.

Gill: So I was talking to Dikembe Mutombo after he swung his elbow, as he famously did, and broke Jayson Williams’s nose. Steve understandably was defending his teammate, said something to me and I said, “Let’s wait until we get in the back to the locker room.” If you do something on the court you’re going to get fined and teammates and referees will break it up. So we all walked to the back and that’s where the incident happened. He pushed me and I pushed him and that was pretty much it. Steve is my very good friend.

Don Casey (New Jersey Nets assistant coach/interim head coach): We got off to a poor start, and it seemed to spin out of control and then for some reason key players started griping about practices.

Gill: I can remember Cal being more intense, more demonstrative in practices. That sort of stuff never bothered me. I’m tough mentally, so it doesn’t bother me with you yelling. I think a lot of the players felt like Cal was treating them like they were in college rather than being professionals. Some of the players, mainly Kerry Kittles and Van Horn, got sick of that. [Keith Van Horn declined an interview request; The Ringer was unable to contact Kittles.]

Casey: Cal then practiced sterner and longer to shake out the losses, but I think some of the players interpreted it as payback rather than something that would be helping them.

McIlvaine: It seemed like no matter what he tried, no matter how he tried to counter it, his answers weren’t working for that team.

Casey: Then they made a mistake trading Cassell for Marbury. After a game or two he felt the Minnesota coaching staff was way ahead of the New Jersey coaching staff, and I think he mentioned that to [owner] Lewis Katz. It didn’t sit too will with John, and I don’t blame him. The rumblings started quickly. Then there was an embarrassing [36-point] loss to Miami on national television, after which Calipari was fired. Those of us who had been around the league realized that the owner got sucked in.

With their deep roster and balanced scoring, the Portland Trail Blazers were built to navigate the compressed schedule better than most other teams; 10 players (Damon Stoudamire, Brian Grant, Isaiah Rider, Rasheed Wallace, Arvydas Sabonis, Jim Jackson, Walt Williams, Stacey Augmon, Greg Anthony, and Kelvin Cato) played in at least 43 games and averaged double-digit minutes per outing. Future six-time All-Star Jermaine O’Neal was the 11th man on the bench.

“We had a really deep team,” head coach Mike Dunleavy says, “and we had a lot of different personalities on the team.”

The results were a Pacific Division title and the no. 2 seed in the playoffs, where the Blazers steamrolled the Phoenix Suns and two-time defending Western Conference champion Utah Jazz before facing the San Antonio Spurs in the Western Conference finals.

Stoudamire: Me and about five or six guys on that team stayed in Portland over the summer. We didn’t necessarily work out together, but we monitored each other. Rasheed always had to work his way back into shape, but it was never hard for him.

Whitsitt: We managed guys. We decided who to practice, and who not to practice.

Dunleavy: I really managed Sabonis’s practices. We would talk before practice and I would say to him, “I need you for a couple of segments here.” It would be more five-on-five stuff or any play sets that we needed to work on timingwise, or anything new and defensive schemes we were going to use against an opponent coming up. After that I didn’t need him.

Stoudamire: Saba never really practiced anyway. He didn’t need to practice. We knew what it was with him. It was game time.

Dunleavy: I looked at two things that season: We have to keep the volatility off this team, and to do that we can’t have a three-game losing streak. That’s got to be a goal. We didn’t lose three consecutive games all season. The other thing was to come in and be like, “Who didn’t get shots last night or the game before?” Then we’d run the first one or two plays for that guy. We had the motto, like, “We have to get so-and-so a shot or he’s going to get himself one and it’s not going to be one we like.” It’s part of the personality of your team.

Stoudamire: We knew that us and San Antonio were the best teams in our conference and that whoever won the conference finals would win the championship.

Mario Elie (San Antonio Spurs guard): We had a good team that got off to a rough start. There were rumblings about Pop’s job. [The Spurs started the season 6-8.]

Daniels: The rumor was that if we lost in Houston, that was Gregg Popovich’s last game as coach of the San Antonio Spurs.

Elliott: The rumor was that Doc Rivers was going to be the [new] head coach if we lost.

Daniels: Avery Johnson told everyone to stay on the bus after the coaches had gotten off, and we talked about how it was time to turn our season around and how this could be Pop’s last game.

Elliott: We won that game going away in Houston. From there, we went on a run. [Beginning with the game at Houston, the Spurs won nine consecutive straight and 18 of 20.]

Daniels: That meeting right there changed our entire season.

Elliott: I have to tell you, I hate team meetings. I think they are the biggest turn-off in the world. We’ve had much more memorable [team meetings]. I think, most of the time, team meetings are an enormous waste of time. They help the media write a story and the players feel good about themselves for a game or two and then it goes right back to the way it was.

Elie: It was the passing of the torch from David to Tim. As soon as that happened, as soon as we established that Tim was our guy, we took off.

Daniels: David was kind of sacrificial, similar like Dwyane Wade was when LeBron came to Miami.

Dunleavy: We played the Spurs two or three times at the end of the regular season. It was probably the worst thing that could happen to us. In those games, our bench beat their bench by double figures. When we got to the playoffs, it was so fresh in their mind that Pop didn’t play a lineup where he didn’t have two of his best guys on the floor. He didn’t go that deep. He shortened it up.

Perdue: I remember how confident we were going into that series because we played them three times so late in that 50-game season.

Elie: It’s two totally different seasons. You don’t remember those three games. Playoffs are a different animal.

Dunleavy: That was the playoff series where Sean Elliott hit the shot where his heels are hanging over the … Yeah, obviously it was clean, but what are the chances of that happening?

Daniels: The Memorial Day Miracle? That was wild.

Elliott: That day my shot felt unbelievable, the whole day, even in my warm-ups where we take five 3s at each spot before the buzzer goes off. I only missed two of those and both had rattled out, and my only miss of the game had rattled in and out. [Elliott shot 8-for-10, 6-for-7 from 3, for 22 points.] The other ones were pure. It felt like it didn’t matter where I was shooting, it was going in. All shooters have those nights where it didn’t matter, all you had to do was peek at the rim and you didn’t have to think about your form and you threw it up there and knew it was going to go.

Whitsitt: Sean Elliott, I swear when I watched it he was on the line. He shoots a jumper from his tip toes and his toes are on the court and his heels are hanging out in the air, but he’s inbounds.

Daniels: Just the footwork to tippy-toe the out-of-bounds line and then the strength and endurance that it takes to knock the shot down from that distance.

Whitsitt: And Rasheed—a 6-foot-11 guy extended—was flying at him.

Elliott: I don’t know how Rasheed didn’t block it. I’ve seen camera angles and the one NBA commercial where it’s a shot from the … other side of the court and it looks like [the ball] went through his fingers. I don’t really remember seeing Rasheed. I just remember turning once I got my feet set. I was supposed to throw down to the low block in to David, that was the play. But when I turned and got my balance, all I saw was the rim. I didn’t see anything else.

Perdue: I remember Rasheed Wallace wouldn’t let it die. He wouldn’t let it go. He was just adamant that it was virtually impossible, but when you look at it from every angle, yeah, he almost stepped out twice, but he didn’t.

Whitsitt: Not saying we would have won the series, but I think if we win that game and go home 1-1 we have a pretty good bounce in our step and turn it into a better series at least versus getting swept.

Perdue: If Sean Elliott doesn’t hit that shot, there’s a possibility that this thing turns out differently. There’s always that discussion of what is worse: a blowout or a one-point loss. They should have won that game. That was devastating.

Elie: I feel like once we came back during the Memorial Day Miracle, we really took their heart. We then went up there, won two games, and swept them. Everything went right for us in the playoffs. We beat Garnett. Then we swept Kobe and Shaq and then we beat the Blazers, who were stacked.

The Spurs’ opponents were the New York Knicks, the first and only 8-seed to reach the NBA Finals. After a decade of agonizing playoff failure, the Knicks made significant changes before the season, trading Charles Oakley to Toronto for Marcus Camby and sending a package headed by John Starks to the Warriors for Latrell Sprewell, who was returning from a season-long suspension.

The loss of Oakley and Starks, beloved fan favorites and avatars of the Knicks’ toughness, damaged team chemistry both on and off the court, and the team limped to a 27-23 finish. But the Knicks clicked in the playoffs, knocking off the top-seeded Miami Heat, the Atlanta Hawks, and, despite a season-ending injury to Patrick Ewing in Game 2 of the series, defeated the Indiana Pacers in the Eastern Conference finals. A miraculous run, highlighted by Larry Johnson’s controversial four-point play in Game 3 against the Pacers, came to an end, however, against the Spurs.

Dudley: Obviously I’m biased, but that was an easy team to root for. We had a lot of hard workers, a lot of warriors who the put the work in.

Childs: It was like we were rock stars. Everywhere we went people wanted autographs.

Dudley: I forget which game it was—I think it was after an Atlanta game—and I got a standing ovation. It was nuts.

Childs: I got a standing ovation at Sue’s Rendezvous.

Davis: We weren’t worried about New York. We were definitely ready and prepared. Everything is going smooth and then I get called for a foul on that four-point play.

Childs: Initially the play was for Allan [Houston], but they ended up switching and [Larry Johnson] caught it, stepped back, and let it go. I’ve never seen the Garden erupt like that. Now, was it a foul? I’ll take it to my grave.

Davis: Oh, heck no. I’ve watched that play I don’t know how many times. I’ve replayed it in my mind I don’t know how many times. If I had to do it all over again I don’t know if I would have done anything different. Larry Johnson was not a 3-point shooter. My thing was give him space—I’m taller than him—when he goes up for the shot, make sure my hand is up and make him shoot a tough shot, and if he hit it, he hit it but I’m not fouling him. Worst-case scenario is that we’re tied up and going the other way.

Childs: My mind-set was we’re only tied, so calm down. LJ was ready to go crazy, put up the L and all that stuff. No, no, you need to calm down, breathe, count to 10. We need this free throw. He saw what I was talking about and calmed down right away. I was the LJ whisperer. Him knocking down that free throw was huge.

Davis: The first thing that came into my mind was, “Oh no, I let my guys down.” That’s a game we are supposed to win. Then there was a whole shift in momentum.

The whole reason the Spurs won the championship was because during the lockout they had pop-a-shots and rims set up in all these church leagues all over the city.Wally Blase, Chicago Bulls assistant athletic trainer

Childs: I think they let up. I think they let out a sigh of relief that they didn’t have to play Patrick. It made us faster. I think we picked up the pace with a lot of pick-and-rolls and cross screens, get some different mismatches.

Davis: When you think about when Ewing is on the floor most things are going through him. In those situations you expect other guys to step up, but you don’t know how. It almost makes it that much more difficult to prepare. Marcus Camby had a great series. It was like what the hell, where did this come from? You’d look up and he had 18 and 9. We didn’t prepare for that. It threw us off.

Childs: It helped us in that series, but it hurt us in the Finals.

Elie: We weren’t super-confident because we knew a Jeff Van Gundy team would play hard.

Perdue: There was a lot of talk like, “Hey, guys, don’t look at the personnel, look at how this team is playing. Don’t compare the guys we have versus the guys they have.” A lot of credit goes to Pop for hammering that home.

Childs: It was tough because LJ was banged up and we were small. Those guys were playing volleyball above the net. And that was a young, deadly Tim Duncan. It was like, “This cat is unbelievable.”

Elie: With Ewing being out and Larry Johnson not being 100 percent, we had the advantage in the frontcourt. Larry Johnson, who was 6-foot-4, was guarding a 7-footer in Tim Duncan. Tim had his way with him.

Elliott: The Knicks played harder than the three teams we played before. They were scrappy and they were tough and they got after it. We swept Portland and they had more talent. We swept the Lakers and they had more talent with Shaq and Kobe and Glen Rice. But the Knicks, they were like some junkyard dogs.

Childs: We fought as well as we could. They were just a better team. You can’t do anything but shake their hand and congratulate them. The messed-up part about it was when that series was over, I went to Kona, Hawaii, with a buddy of mine. We walk into the golf course and as soon as we walk in—excuse my language—I fucking walk right into David Robinson. I’m like, you’ve got to be kidding me. He wants to talk and smile. “You got room for one?” “No. We don’t have room for one. I don’t want to see you right now.” He was cool and cordial. He had a place on the island and invited us over for a luau. We didn’t go.

Elliott: I talked about that [series] with Tim a while back and he was like, “We should have swept that series.” [The Spurs won in five games.] He’s still mad about it. He’s still mad we lost that game at Madison Square Garden.

Perdue: I think one of the reasons why we won the championship that season, if not the main reason, was that we stayed together. We would meet four or five times a week at this health club in San Antonio during the lockout and hold team workouts. We would work out and then go to the gym next door and much like a practice go through drills, work on things in the half court. Then we would play four-on-four or five-on-five, and it wasn’t like we were just running up and down the floor. It was competitive. It would be like, “Hey, it’s getting a little ragged, let’s take a break and come back.”

Blase: The whole reason the Spurs won the championship was because during the lockout they had pop-a-shots and rims set up in all these church leagues all over the city. They had a dozen or so of these workout coaches meeting Duncan and those guys everywhere around San Antonio that wasn’t the practice facility. That really happened.

Perdue: There was never a single coach at any one of those workouts. There was never anybody that was affiliated with the San Antonio Spurs at any of those workouts. It was just players.

Blase: Guys who worked for the Spurs love to say how great the Spurs were at everything. You’re in San Antonio driving to the AT&T Center and guys are pointing out all these church gyms like, “Yeah, there’s one of the places where I’d meet Tim.” It would be like a former [intern] who was now an assistant coach. The Spurs were famous for “interns,” guys that weren’t full-time employees so they could run around the city.

Perdue: During the lockout when the union would have their conference calls, we would get together as a team at the health club and listen in. We noticed that a lot of guys were getting on the call as individuals where we were getting on as a team every single week. It was a daily topic during the lockout: How do we approach it and how do we stay together?

Billy Hunter kept a memento from the 1998-99 lockout in his office up until he was fired as NBPA executive director in February 2013. “There was a picture of Patrick and me and other ballplayers and David Stern and a group riding on white horses trampling over us, this cavalry led by David Stern,” Hunter says of an illustration from the January 18, 1999, issue of Sports Illustrated, which he hung on his wall. “The caption was something like, ‘The union got rolled by the owners.’”

The lockout was bad for business, both in the interim (Sports Goods Business reported that NBA-licensed sales had declined nearly 50 percent through the 1998 holiday season) and over the long term. During the lockout-shortened season, attendance was down 2 percent from 17,117 per game in 1997-98, and would not again exceed 17,000 until the 2003-04 season. Television ratings also suffered, with regular-season ratings falling from 6.3 million viewers per game during the 1997-98 NBA season to 4 million during the 2000-01 season. Ratings for the NBA Finals have never reached the heights of the Bulls-Jazz rematch from 1998 (which averaged an 18.7 rating and 29.04 million viewers), bottoming out in 2007, when the Spurs swept the Cleveland Cavaliers, a series that averaged a 6.2 rating and 9.29 million viewers.

But the NBA enjoyed labor peace for the next decade. The 1999 CBA was essentially extended with minor changes in 2005 for six years before the owners locked out the players once again in 2011, a work stoppage that resulted in more concessions from labor, with the players’ share of basketball-related income shrinking from 57 percent before the 2011 lockout down to a 50-50 split.

Given that it’s sports, we want to characterize everything, even the end of a labor negotiation, as a win or a loss. And though the 1999 collective bargaining agreement strengthened the union’s middle class, the owners won the 1998-99 lockout. Rolled? That’s up for debate.

Charles Grantham (NBPA executive director, 1988-95): Once that imbalance is created as it has now in the league, you can’t negotiate those things back. You can’t out-negotiate the league now to get your 8 percent [of BRI] back.

The owners won for sure.Kevin Willis, Toronto Raptors center

Perdue: The players collapsed like a house of cards.

McIlvaine: I think the owners made out better.

Keefe: I think the impression of the Sports Illustrated [illustration] of David Stern kind of running roughshod over the union is a lasting impression of how I feel like that deal came out. That being said, fast-forward 20 years, and the league is healthy, the benefits are great for the players, and they are much better with long-term care like 401(k)s and health benefits.

Jim Thomas (Sacramento Kings owner): It wasn’t a perfect contract for the owners, certainly from my viewpoint, the small-market viewpoint. [But] it turned out well and the league has continued to grow and prosper. This recent TV contract has been a windfall for the owners. My wife always said that I sold the team too soon, and she was absolutely right.

Klempner: What the owners wanted was a hard cap and a much lower percentage [of BRI], and they didn’t get either of those.

Kessler: If you look at where they started and where they ended up, then the players won, right?

I don’t think anyone really won. People on both sides lost a lot.Mark Bartelstein, agent

Willis: The owners won for sure.

Wasserman: In 1997-98, player compensation salaries and benefits reached a billion dollars for the first time, and at the end of the ’99 agreement in ’04-05, player comp was $1.8 billion. So in this deal where we got our “ass kicked,” player compensation rose 80 percent.

Dudley: We went backward, so the owners won in that way. But the players won in not having a hard cap. I think in that regard there were winners on both sides.

Mark Bartelstein (agent): I don’t think anyone really won. People on both sides lost a lot.

Perdue: If anything positive came out of that lockout from the players’ standpoint, it’s that I think that’s when things really started to turn around as far as players being able to grab more power and players unifying.

The stereotype was not so much that professional athletes couldn’t stick together, but that black professional athletes could not maintain unity. I think they destroyed that stereotype.Hunter

Falk: I am a big fan of LeBron’s. Right on the eve of the 2011 lockout, I was in Miami visiting Juwan [Howard], and Juwan had a scheduling conflict. He agreed to have dinner, but one of LeBron’s guys had gotten engaged, so he asked me if I would mind going to dinner, they were having a little reception. I said sure. At the end of the dinner, I actually bumped into LeBron. I went up to him and I said, “Get off your ass and get involved. They’re stealing your money.” That’s what I told him. I think LeBron is a very intelligent guy. People like him have got to be involved, because when they put a cap on his salary, the guy should be making like $80 million a year.

Hunter: The players demonstrated like never before that they could stick together. The stereotype was not so much that professional athletes couldn’t stick together, but that black professional athletes could not maintain unity. I think they destroyed that stereotype.

Glass: The lockout didn’t really make a whole lot of sense. The players were going to survive; the salaries were going to keep going up. The owners were making millions and millions of dollars even though they said they weren’t. But there were so many people who got hurt, like the people who worked at the arenas, the parking garages, and the concessions stands. People needed that money. I always had a problem forgetting that.

Falk: The whole thing was an unmitigated disaster.