Last spring, Jason Witten sat in Jerry Jones’s office in Frisco, Texas. Out the window, the two men could see the practice field where Witten had been his tough-as-nails, wildly inspirational tight end self. Witten was thinking about leaving the Cowboys to be an announcer on Monday Night Football. After some consideration, Jones gave his blessing. “Go be John Wayne,” he said.

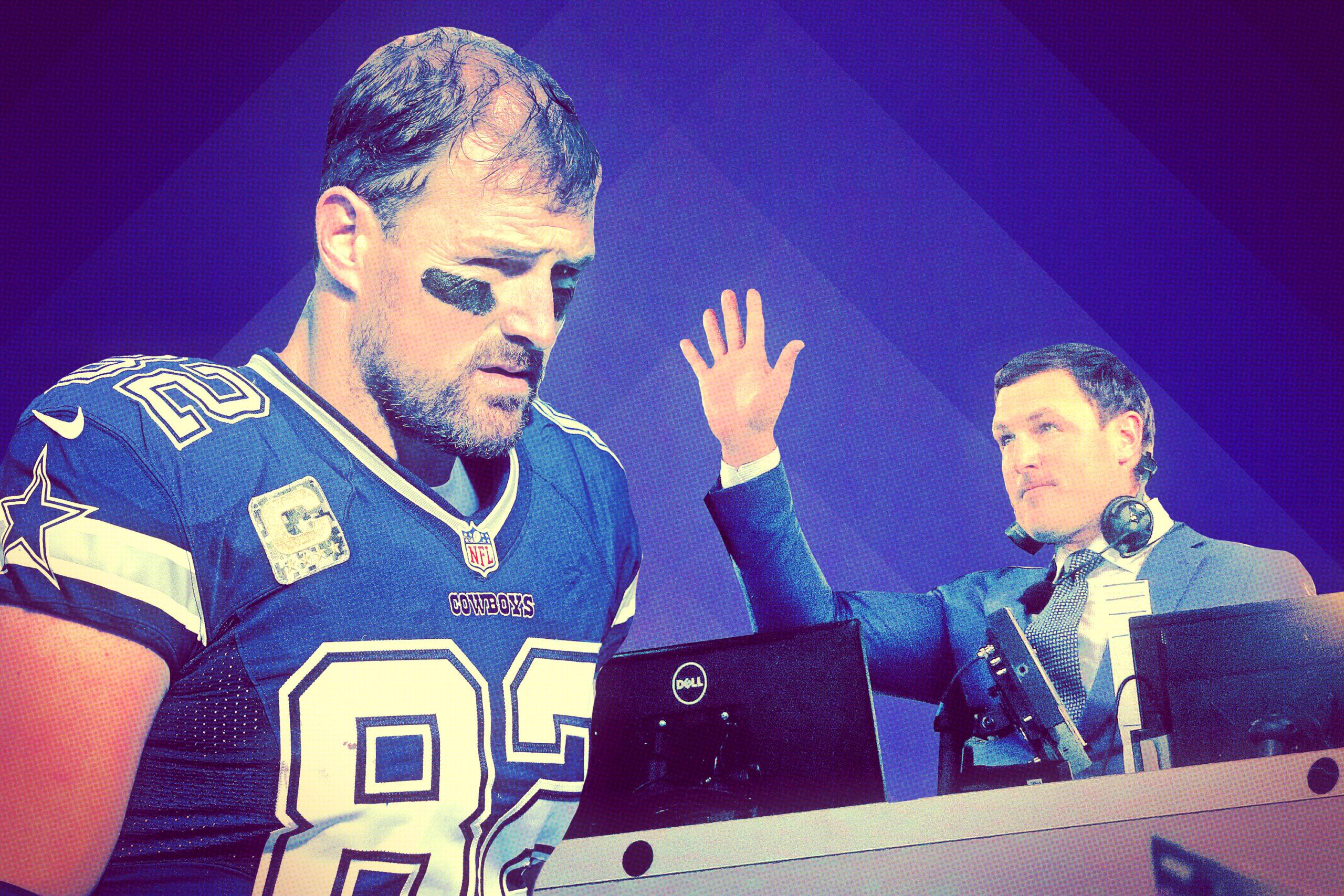

Off Witten went to Monday Night. There, Twitter did to Witten what he used to do to linebackers. A lot. Every week. Thursday, Witten shockingly announced that after a single season in the booth he’s coming back to the Cowboys. John Wayne has returned to the ranch.

I talked with Witten at the Super Bowl earlier this month about his first, turbulent season. For a year, I’d heard, “You can’t believe how impressive this guy is in person!” so many times that I almost didn’t believe it.

The thing is, outside the TV box Witten is impressive. He arrived wearing a quarter-zip that covered his massive shoulders; his forehead was unlined; his hair had that suspicious post-career thickness. Talking to Witten was like watching an instructional video about how to ace a job interview. The words tumbled out of him. He never seemed to pause. If you didn’t give him the Monday Night job, you’d consider him for secretary of defense.

For Witten, the weirdest thing about doing Monday Night Football was the criticism. Witten had never gotten bad press in his life. Now, on TV, he was getting his ass kicked on Twitter every week. It started in his first preseason game, when he appeared on screen holding his ESPN microphone almost directly in front of his face. Jason, you wanted to say, we can SEE you. You’re on TV.

Witten offered the world a small treasury of malapropisms. “He pulls another rabbit out of his head.” The new roughing-the-passer rule was “a little bit to the left wing.” Witten was always talking about how much he loved “ball.” He thought his best games last season were the Chief-Rams classic, ESPN’s playoff game, and, oddly, the alternate broadcast that he, Joe Tessitore, and Booger McFarland called of the College Football Playoff championship game. That was when Witten didn’t worry so much about the machinery of TV and just talked.

But once Twitter is in your head, it’s hard to get it out. After a game, Witten didn’t even need to look at it. He could tell if he screwed up just by glancing at his phone. When he’d had a bad game, his texts said something like, Hang in there.

After calling the Pro Bowl, Witten handed the Most Valuable Player trophy to Patrick Mahomes II and Jamal Adams. The trophy broke when he picked it up. Witten thought, That’s gonna be on Twitter, too. It was.

Witten tried to think of broadcasting like he thought of football. What are the metrics of success? He figured out that pointing out one thing after a play is better than pointing out three or four, and saying something like, “He’s looking for Gronk outside,” is sometimes preferable to naming the scheme or play.

Early in the season, Witten was overloading his crew with notes on the game. Later, he started telling them things like, “Let’s focus on the right guard and the defensive tackle.” Witten was figuring out that lightly worn nerdery is about as much as television can stand.

Cowboys fans noted a certain irony in Witten’s struggles. In Dallas, he was close to the perfect tight end and perfect guy. His number was shown on a downtown building when he retired; they named a baby giraffe at the zoo after him. Tony Romo was the quarterback with the fatal flaws. On TV, they effectively switched places. Romo was perfect and Witten was flawed. That had to be really weird.

Witten could feel Romo’s shadow. Not in an aggressive or jealous way—he certainly liked Romo. But for the people who call football games on TV, Romo is a category killer. Witten thought he could’ve predicted plays, too. But then he’d seem like a copycat.

It’s no surprise that Witten wants to be a Cowboy again. He missed certain things about football, like those postgame plane rides when the players could forget about what had just happened and not think about what was next. It was a lovely interregnum in a hectic world. Last year, Witten asked that the Monday Night crew sip some tequila (a gift from an ESPN Deportes announcer) on the bus back from the stadium. He wanted to re-create the sensation of living in the moment.

Witten had a few things he wished he could do over about his first season. He wished he’d made a better first impression. He wished he’d been bigger early on, so he could have matched Tessitore’s energy.

He remembered a game against the Eagles in his second year with the Cowboys. That was his coming-out party: nine catches for 133 yards. It was when he went from an “interesting prospect” to “this guy could be a Hall of Famer.” On TV, Witten thought maybe he’d had that same feeling. At least, he thought he knew how to be good.

Witten thinks of himself as the most coachable guy in the universe. He had a plan to get better. He was going to spend the offseason watching all his Monday Night games. He was also going to watch other announcers’ games with the sound down. He would announce a play, then turn the sound up and compare his call with the announcer’s.

He was going on a broadcasting vision quest. He would visit ESPN’s Kirk Herbstreit, who could take complicated schemes and talk about them in clean, simple language. He would visit with Jeff Van Gundy to ask about prospering in a three-man booth. He would go to Northern California to visit John Madden, the ultimate broadcasting sensei. He and Madden might even watch some tape together.

Witten understood that it’s the schedule, more than the announcers, that determines the success of Monday Night Football. ESPN had much better Monday Night games last year, but some people felt that was partially built on luck. They got the game of the year with Chiefs-Rams. They got the last drop of Fitzmagic in Week 3. Drew Brees broke the passing record in October on a Monday night.

He didn’t think ESPN could take the chance that such luck would repeat itself in 2019. Along with Tessitore, he’d been part of ESPN’s charm offensive with the NFL. More than that, Witten wanted to understand the schedule. He knew Monday Night wouldn’t ever get a half-dozen monster games. So Witten wanted to figure out how they could pick an up-and-coming team from the previous year—like the 2018 Chiefs—and get them on Monday Night as much as possible.

The Monday Night booth felt more organic when the Boogermobile went to impound late in the season. But ESPN never quite figured out how to showcase Witten, how to give him a gimmick. His biggest moment was when he talked about his own experience with domestic violence during a Redskins-Eagles game (which itself stirred up controversy, since Witten had played with Greg Hardy). This spring, the network was probably going to give Witten his own version of Jon Gruden’s draft camp, so he could be a less craggy version of the guy he replaced.

Witten isn’t going to single-handedly fix the Cowboys offense. He hasn’t had more than 80 catches in a season since 2012. But joining the Cowboys again takes Witten away from sports TV and puts him back into the place where people thought he was something close to perfect. It’s a small irony. To be John Wayne, Witten had to ride home.