King Kong Bundy, who died on Monday at age 61, was the first menacing wrestler many of us 1980s kids ever saw. Bundy was a mountain of a man, a 450-pound roadblock of rectangular flesh, and he stomped and splashed his foes into oblivion. His bloodied face at WrestleMania 2, jammed against the bars of the steel cage by a heroic Hulk Hogan fighting against both Bundy and the rib injuries Bundy had inflicted, still haunts my dreams.

There was no subtlety with Bundy, no fancy top-rope dives or even more modern-era monster moves like chokeslams and powerbombs. Nope, he just squashed you like a bug, as he did in his nine-second (actually 17, but who keeps count in kayfabe?) victory over S.D. Jones at the inaugural WrestleMania. He was our first exposure to a big, bad man, a foil for both Andre the Giant and Hulk Hogan, and he played his role to perfection.

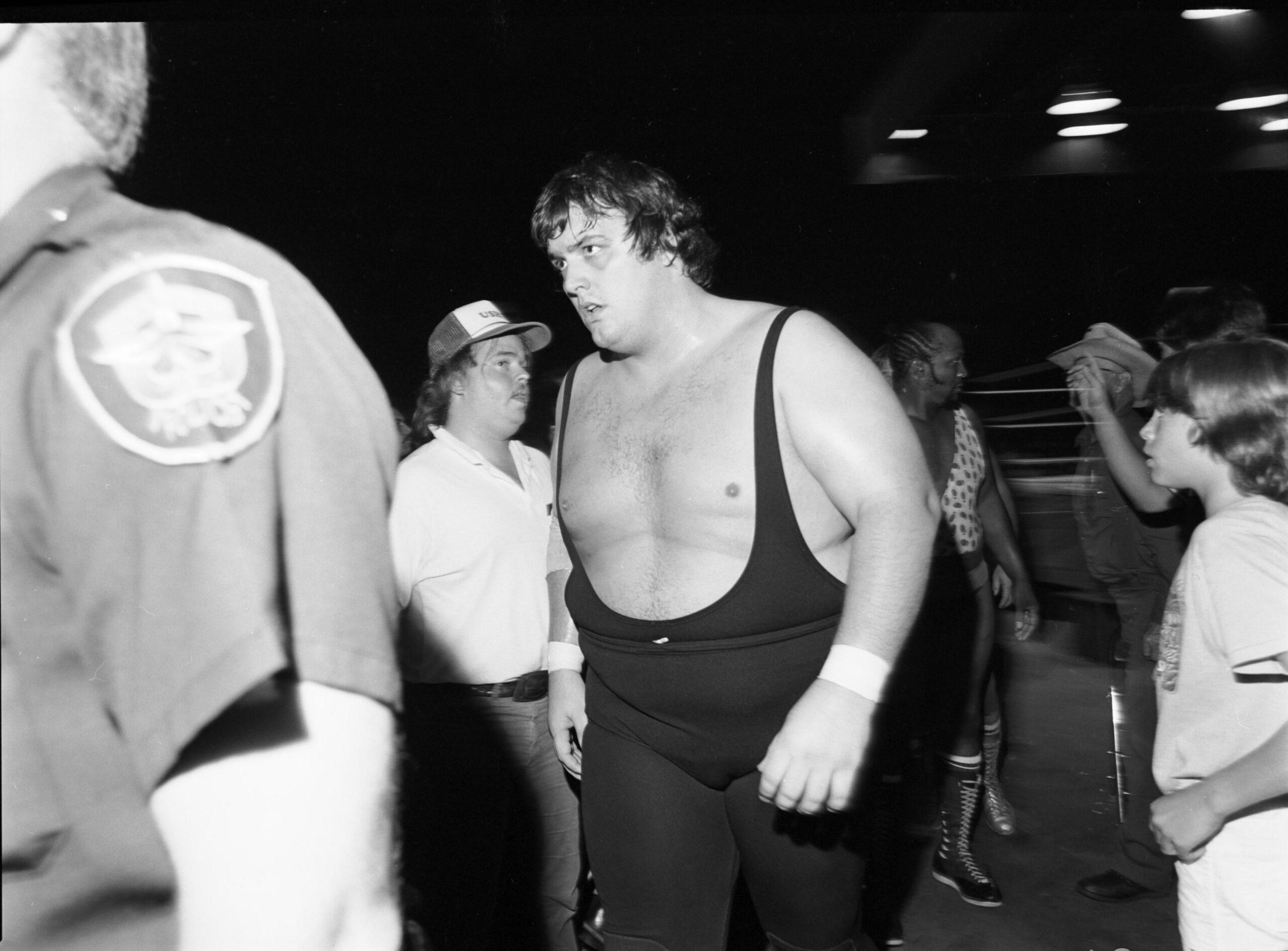

However, Bundy wasn’t always a big, bad man—he was originally just a big man-child with a shaggy and rather full head of hair. After some seasoning at Larry Sharpe’s “Monster Factory” in his home state of New Jersey and some appearances as an enhancement talent for the pre-expansion WWF, he launched his career as “Big Daddy Bundy” in the Dallas-based World Class promotion. He wrestled in jeans and a rope belt, a goofy oversized fan favorite in the Haystacks Calhoun mold of such big boys.

But after a couple months of trial and error, Bundy found his manager, in the form of the extremely effective heel mouthpiece Gary Hart, and his gimmick, in the form of a black two-strap singlet that made him look to all the world like a block of marble. He fell out with the Von Erich family, the leading good guys (and owners) in World Class, and became “King Kong” Bundy, one of their most ferocious foes, losing to patriarch Fritz in a retirement match and losing his hair to Kevin Von Erich in a bout in San Antonio, Texas.

The resulting bald-headed brute, finally the monster he was meant to be, then left World Class to terrorize the rest of the U.S., cycling through stints with legendary promoters such as Bill Watts, Verne Gagne, and Jerry Jarrett. It was with Watts’s Mid-South Wrestling that he refined one of the most memorable aspects of his gimmicks, demanding a five-count instead of a three-count after beating down a hapless jobber. And it was while wrestling with Jerry Lawler and Rick Rude in Memphis that he truly began to improve as a worker—a rarity at that time for a 400-pounder—who could work 10-minute main-event matches against top stars.

In 1985 Bundy entered the WWF, and, by extension, my life. He looked to be ancient even then, an Easter Island statue waddling around on a pair of thick pillars, but he was only in his late 20s. Even in the charisma-driven WWF, Bundy never really rocked the mic, relying on the support of Bobby Heenan much as he had with Gary Hart in World Class, but his sheer mass always rocked the ring. When he jumped around a prone foe in preparation for a splash or sandwiched them in the corner, it was impossible to ignore his size.

Bundy was far from the first “King Kong.” There was the titular ape in the RKO film of the 1930s, and then a host of grapplers, such as ex–Canadian Football League legend Angelo “King Kong” Mosca, who bore that moniker. Even Bruiser Brody, that wild-haired free agent, sometimes went by “King Kong” in certain territories. But Bundy was the man who really came to own that name, owing to the WWF’s marketing machine and his ubiquity on national television programming from 1985 to 1987. For kids who grew up on a diet of garbage Saturday morning cartoons and unhealthy sweetened cereals, kids who stayed up late to watch Saturday Night’s Main Event on NBC whenever it preempted Saturday Night Live, he was our King Kong.

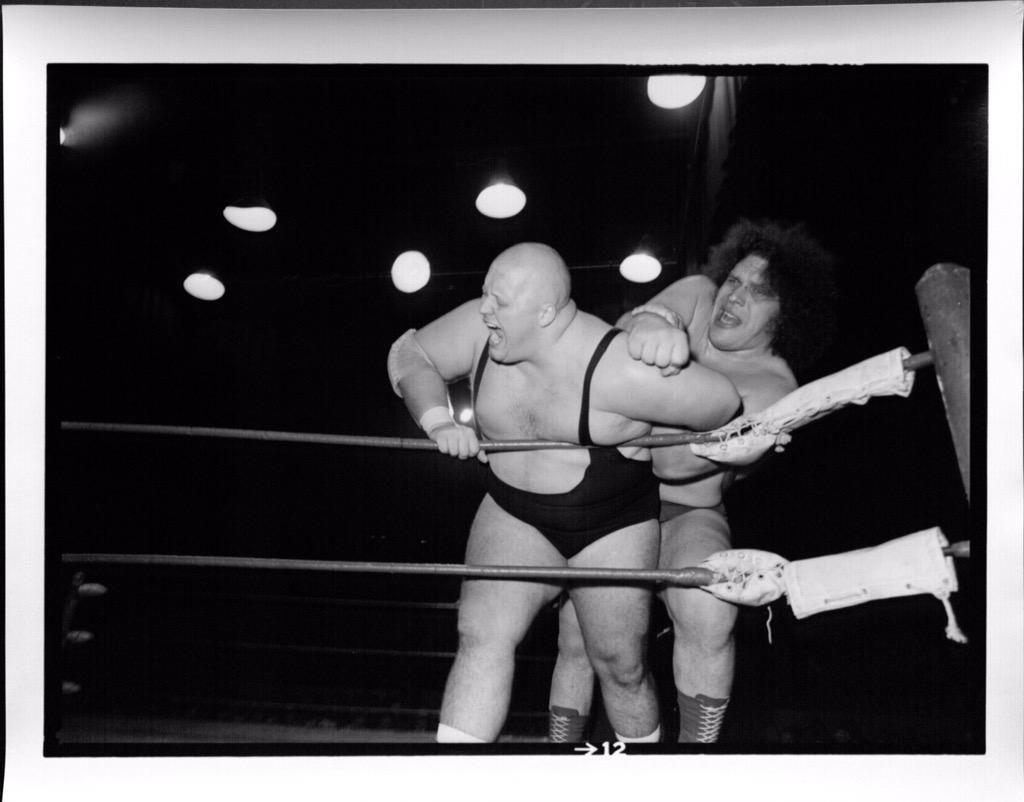

The Bundy of this golden era had four signature moments. The first came as a sometime-partner of “Big” John Studd, an ex-basketball player and near-giant also in Bobby Heenan’s employ, in an ongoing war against Andre the Giant, who was wrestling under a mask as “Giant Machine.” The second consisted of crushing jobber-to-the-stars S.D. Jones, a thunderous bump that I rewound many times on the VHS tape of the pay-per-view I kept renting from the local video store. The third happened when Bundy smashed Hogan’s ribs, at least in story line, only to be vanquished and busted open at WrestleMania 2 by the hulked-up Hulkster—a fascinating R-rated moment in a cartoon promotion. And the last came at the tail end of Bundy’s first run, as he found himself wrestling alongside heel midget wrestlers Little Tokyo and Lord Littlebrook against Hillbilly Jim and his team of the Haiti Kid and Little Beaver. Bundy lost that match after body-slamming Little Beaver—he was disqualified for physically assaulting one of the little persons—and then, as he had done so many times before, smushing him with an elbow drop. He stepped away from the ring in 1988, wrestling sporadically until he returned to the WWF in 1994.

Bundy, whose wrestling surname was inspired by Ted Bundy, twice appeared on Married… With Children, making a cameo in 1988 as a member of the Bundy clan—who had been named in his (not serial killer Ted’s) honor by fans and showrunners Ron Leavitt and Michael Moye—then later as himself during his 1995 WWF comeback. It was during this comeback, when he was part of Ted DiBiase’s “Million Dollar Corporation” stable, that, despite his nefarious leanings, I began rooting for this big, bad, and still-not-actually-old man. (He was only 38.)

By 1995, Bundy looked the same, as if he had been preserved in a tar pit somewhere, but was slightly slower afoot and no more scintillating on the mic, and he paled in comparison to more athletic big men like Big Van Vader. Yet he represented a link to my own technicolor past—the great heyday of Saturday morning cartoon wrestling!—for which I had already, as a cynical tween, grown nostalgic. This late iteration of Bundy ended up back at WrestleMania XI, where he jobbed out to the Undertaker, last decade’s cuboid villain losing to the rope-walking heel of the future. I desperately wanted my past to prevail, but it was a lost cause: It was the Undertaker at WrestleMania, and Bundy’s fate was sealed.

For a man whose steps shook the earth, King Kong Bundy’s long last act proved a rather quiet one. He left the WWF in 1995 and went about his business on the independent circuit, headlining shows against other stars of yore and giving the requisite shoot interviews about days gone by. He was part of a lawsuit against the WWE brought by Konstantine Kyros, now just one among many old grapplers alleging brain damage, but Kyros’s attempt to win some NFL-style justice for the squared circle’s many CTE sufferers came to naught when a federal judge dismissed the case in 2018.

Bundy was an impassive, impressive villain, a Jersey bruiser who wore a permanent scowl, and the shadow he cast on the sport was so long and wide that it seemed as if he had been a star villain forever. But his time in the spotlight was not nearly as lengthy as it seemed, enhanced as it was by the sheer irreproducibility of his vast, right-angled block of mass. Yet Bundy, in death, now looms even larger than he did in life. Perhaps it’s the humanity retroactively instilled upon Andre the Giant placed up against Bundy’s real-life inscrutability that made him seem so monstrous, even in his dotage. Maybe it’s the name, the aura, the carnage he wreaked before he disappeared into the wilds. Or maybe it’s just the man: the scowl, the size, the shape of him. For my generation, he was fear and menace distilled. And his legacy will remain as huge as his terrifying presence.

Oliver Lee Bateman is a journalist and sports historian who lives in Pittsburgh. You can follow him on Twitter @MoustacheClubUS and read more of his work at www.oliverbateman.com.