The 50 Best Movies of 1999, Part 1

From ‘American Beauty’ to ‘The Mummy,’ from ‘She’s All That’ to ‘Deep Blue Sea,’ the Ringer staff sorts out one of the best years in film historyWelcome to 1999 Movies Week, a celebration of one of the best years in film history. Throughout the week, The Ringer will highlight some of the year’s best, most interesting films, but there’s no better way to prove what a high-quality, diverse year ’99 was at the box office than by ranking the movies. Here is Part 1 of The Ringer’s ranking of the 50 best movies of 1999. Come back tomorrow as we reveal the top 25.

50. The Straight Story

Rob Harvilla: Believe it: Two years before Mulholland Drive, David Lynch directed a warm-hearted (and G-rated, and Disney-approved) drama about an aging World War II veteran who braves a 240-mile trek on his riding mower to reconnect with his estranged brother. It’s beautiful, and shockingly wholesome, and all the more powerful for the shock.

What is the best behind-the-scenes anecdote about this movie? The title is not just Lynch’s way of telegraphing his earnestness: The Straight Story is inspired by the true tale of Alvin Straight (played by Richard Farnsworth), who in 1994, at 73 years old, made just such a journey (from Iowa to Wisconsin) on just such a lawn mower. Look at this picture. Longtime Lynch cohort Mary Sweeney co-wrote the script with John Roach after reading about Straight in The New York Times; as for Lynch himself, “In the editing room I cried like mad,” he later recounted. “I don’t tend to cry easily, but this story touches a sore point in me.”

Who stole this movie? As Alvin Straight, Richard Farnsworth radiates grizzly dignity (he got an Oscar nomination for Best Actor, but lost to Kevin Spacey in American Beauty), and Sissy Spacek and Harry Dean Stanton are cast just as perfectly. But The Straight Story belongs to composer and longtime Lynch cohort Angelo Badalamenti, whose score is a hypnotic and ungodly beautiful thing, soothing and soaring without the usual Lynchian undertone of abject despair.

49. Bowfinger

Adam Nayman: Steve Martin has denied that his script for Frank Oz’s behind-the-scenes Hollywood comedy—about a paranoid movie star (Eddie Murphy) being manipulated into believing the plot of an alien-invasion blockbuster is really happening—set out to take shots at the Church of Scientology. But the funniest thing about Bowfinger (which also stars Martin as a schlocky movie producer) is its depiction of the cultlike self-help sect MindHead, which provides this otherwise inoffensive satire with a serrated edge.

Who stole this movie? Bowfinger’s killer cast includes Robert Downey Jr. (still a couple of years away from his comeback but in fine form), Heather Graham and Christine Baranski, but the MVP is Terence Stamp as Mindhead’s charismatic leader, Terry Stricter, a superficially benevolent but shrewdly calculating guru who gets laughs every time he finesses Murphy’s flustered Kit Ramsey. “There is no giant foot trying to squash me,” he says in the even, measured cadence of a mantra. “I feel like I might ignite, but I probably won’t.” Stamp has always excelled at villains, and, while Terry is more opportunistic than evil, he makes a wonderful, droll foil for the anxious characters around him.

What is the best line from the movie? “We’ll be just like Bogey and Bacall” exclaims Bowfinger to Graham’s wannabe starlet Daisy, whose reponse—“Who?”—is a joke that cuts two ways, skewering the (much) older producer’s classic Hollywood delusions while suggesting his Gen X lover doesn’t have much of a frame of reference. If Bowfinger works as a movie about how some things about movie-making (i.e. the bad parts) never change, invoking Bogey and Bacall suggests a deft balance of irreverence and nostalgia—and shows Martin at his double-edged best.

48. Girl, Interrupted

Lindsay Zoladz: A crucial entry in the sad-teenage-girl canon, this star-studded adaptation of Susanna Kaysen’s coming-of-age-in-a-mental-institution memoir is basically Hollywood’s take on The Bell Jar.

What’s the one thing about this movie that’s aged the worst? The decision to put a teenage Elisabeth Moss in particularly garish burn-victim facial prosthesis.

Who stole this movie? A magnetic Angelina Jolie, in the performance that led to the Oscar acceptance speech that let the world know just how much she loves her brother.

47. Pokémon: The First Movie

Claire McNear: Pokémon: The First Movie is relevant not so much for what it is—a so-so kids’ movie in which we all learn a valuable lesson about friendship—than for what it represented: the international mania of Pokémon descending on the U.S. in full force.

How did this movie change popular culture? It’s hard to overstate the heights of Pokémania circa 1999. The GameBoy games had come out in the U.S. in the fall of 1998 in a coordinated marketing blitz, and demand for the movie upon its American release in November of the following year was intense. Burger King launched a toy giveaway in concert with the movie’s release, which prompted a nationwide rush on the chain and a shortage so severe that Burger King’s North American president bought ad space to run apologies in newspapers, including The New York Times. The First Movie debuted on a Wednesday and so many kids blew off school in what would become the biggest Wednesday movie opening ever that a new illness was coined: the “Pokéflu.”

Who stole this movie? I’m going to have to go with … the ethics dilemma. The premise is that human scientists splice DNA to create in a lab the new Pokémon Mewtwo, who is stronger and smarter than any of his (its?) Pokébrethren, speaks perfect English, and is tortured by questions of his own nascent personhood. Mewtwo breaks out and invites Ash, Misty, Brock, and the gang to his castle lair—Agatha Christie, Pokémon style—from which he plans to destroy both mankind and all Pokémon, whom he insists are slaves to the humans who’ve captured them. The Pokémon in attendance insist they’re not—we’re friends, pika-pika—and everyone makes peace in the end. But, uh, Mewtwo is … sort of not wrong? Pokémon is problematic. Please come to my TED Talk.

46. The Best Man

Amanda Dobbins: A classic “drama before the wedding” setup—the bride slept with the best man! The best man loves someone else! All the other friends are deeply involved in their business! There’s a roman à clef subplot because social media doesn’t exist yet!—with an all-star African American ensemble and an iconic Electric Slide. Remember when they made romantic comedies?

How did this movie influence films to come? The Best Man was the first feature from Malcolm D. Lee of Girls Trip fame, a breakout of sorts for Terrence Howard, a sleeper box office hit, an inspiration for the delightful The Best Man Holiday, and yet another excuse to see Taye Diggs shirtless. The shame is that Hollywood didn’t capitalize more on a crowd-pleasing, star-launching studio film.

What is the best line or moment from this movie? Every movie needs one of these:

45. October Sky

McNear: October Sky, a film about teenage Jake Gyllenhaal’s quest to do more homework, was seemingly engineered in a lab to be played for students by sonorous substitute teachers. It’s based on the life of retired NASA engineer Homer Hickam, who made good on his love of rockets and escaped his coal mine–dominated hometown, so its tearjerker properties are at least mostly earned.

Who stole this movie? World, meet Jake Gyllenhaal. He was just 17 when the movie, his first, was filmed, and its success catapulted him into the spotlight; his next film was Donnie Darko, so, yeah, our guy got weird quick.

What is the best line and/or moment from this movie? After Laura Dern, who plays the Rocket Boys’ devoted science teacher, gives young Homer a textbook as a birthday present, he delightedly declares that “It’s the best present anyone’s ever given me.” I’m not sure how many times I was obligated to watch this movie in school—ten? 20? 100?—but I can still hear the groans following this line.

44. Bringing Out the Dead

Nayman: Martin Scorsese and Paul Schrader’s spiritual sequel to Taxi Driver follows a strung-out, desperate paramedic (Nicolas Cage) navigating New York’s mean streets in a battered ambulance (a scenario that lends itself to all kinds of kinetic, agile camerawork and driving, urban-ethnographic energy). Cage’s Frank Pierce is as tortured as Travis Bickle, but the story’s arc leads away from vigilante justice to a quieter, more wrenching form of personal and spiritual redemption.

What is the best line or moment from this movie? I was working in a Blockbuster Video store in 2000, when Bringing Out the Dead came out on VHS, which meant that once an hour, on the hour, I’d get to listen to the preview on the store’s round-the-clock demo tape—a two-minute promo highlighted by Ving Rhames’s eccentric medic, Marcus, performing a self-styled exorcism on an OD’ing clubgoer named I.B. Bangin’. It’s an electric scene, melding medicine and mysticism with the sacred and the profane, and it’s as harrowing as it is hilariously funny. Years from now, when I am on my deathbed, I will have forgotten most things, but I will remember Rhames’s melodious, thundering, gospel-flavored delivery of the line “RISE UP, I BE BANGIN.”

How did this movie change popular culture? It didn’t, and in some ways, that’s what makes it interesting: Coming after the perceived Goodfellas retread of Casino and the biopic detour of Kundun—a wonderful, underrated movie, even if only Christopher Moltisanti thought so—Bringing Out the Dead was hailed ahead of its release as a “return to form” for its director but ended up being overshadowed by the rest of 1999’s bumper crop, including several films (Fight Club, Three Kings, even The Boondock Saints) that drew on Scorsese’s influence and bag of stylistic tricks. It’s a skillful, powerful movie whose impact was muted, which makes it all the more valuable for rediscovery now that Scorsese’s career has been on a critical and commercial uptick in the 21st century.

43. Galaxy Quest

Ben Lindbergh: A spoof of Star Trek and its rabid fan base that could easily have crossed into mean-spirited territory, Galaxy Quest is instead an affectionate and warmhearted send-up that celebrates the convention/sci-fi subculture it perceptively parodies.

What is the best behind-the-scenes anecdote about this movie? DreamWorks hired Harold Ramis to direct Galaxy Quest while Analyze This was still in postproduction, which could have given Ramis two entries on this ranking. But according to Jordan Hoffman’s 2014 oral history, Ramis wanted Alec Baldwin to play the lead role of Jason Nesmith, veteran portrayer of the fictional Galaxy Quest’s Commander Peter Taggart. Baldwin turned it down, as did Kevin Kline and Steve Martin. Ramis then declined to do the movie with Tim Allen as the lead. When Ramis saw the movie, he praised Allen’s performance, which blended Yul Brynner’s sensitivity with a Shatneresque bravado. As the late Alan Rickman recalled, Allen embodied Taggart when the cameras weren’t rolling. “Tim Allen used to kick the door open to the makeup trailer,” Rickman told Hoffman. “We would be all lined up and he would say, ‘Number one is here!’”

What is the best line and/or moment from this movie? Rickman’s self-loathing actor, Alexander Dane (who plays the Spock-like Dr. Lazarus), uttering the obligatory catchphrase that’s become a curse, “By Grabthar’s Hammer,” at the opening of an electronics store.

The halting, dead-eyed delivery is exquisite.

42. The Mummy

Miles Surrey: The Mummy is basically a dumbed-down Indiana Jones adventure, featuring a mummy. In other words, it is perfect.

What’s the one thing about this movie that’s aged the worst? Brendan Fraser’s explorer Rick O’Connell is full of charisma—it is Brendan Fraser, after all—but the budding romance between Rick and Evelyn (Rachel Weisz) does not get off to a great start. It begins with Rick blurting out “Who’s the broad?” and ends with him kissing her without her consent. The ’90s!

How did this movie change popular culture? Well, clearly it made some kind of impact, since The Mummy produced two financially viable (if not as entertaining) sequels and a 2017 reboot that was intended to be the starting point for a “Dark Universe.” (Lol.) And Chris Pratt has sort of fashioned himself into a present-day, slightly problematic equivalent to the Brendan Fraser adventurer types. I’m not sure pop culture has progressed post-Mummy, but at least this version is currently available on Netflix.

41. Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai

Chris Ryan: Maybe the last cult classic? Ghost Dog was too weird to make a Tarantino-style crossover into mainstream culture, but its enigmatic mixture of Eastern mysticism and downtown New York cool, exemplified in its collector’s item score by Wu-Tang Clan’s RZA, was beloved by indie film nerds and martial arts movie mavens alike.

Who stole this movie? The RZA score—the Japanese version, not the widely available “album version,” you herb—was the best-kept secret of late-’90s beat-diggers who didn’t mind stumping for import prices when it came to crusty Muscle Shoals loops, baked in Philly Blunt smoke. Great cameo, too.

What is the best line or moment from this movie? This is a genre film that makes very few concessions to genre conventions, but even a maverick like Jim Jarmusch needs to play the hits every once in a while. Every great martial arts movie needs a training sequence, and Ghost Dog does not disappoint with this dreamy sequence of Forest Whitaker’s hitman training among his beloved pigeons.

40. Superstar

Alison Herman: If not the only good movie created from a Saturday Night Live character, it’s certainly in the top three. Before the unhinged teen-girl sexuality of Pen15, there was Mary Katherine Gallagher.

How did this movie change popular culture? Molly Shannon is a force of nature, and the movie-sized version of her signature SNL character is a rare opportunity for a performer now widely regarded as a character actress to take center stage. Shannon hasn’t had too many leading roles since, let alone ones that allow her to go as balls-to-the-wall as Mary Katherine’s horned-up dreamer, but the career that’s currently giving us a splendid performance on The Other Two likely wouldn’t be possible without this.

What’s the one thing about this movie that’s aged the worst? I’m gonna go with casting then-32-year-old Will Ferrell as a high school heartthrob.

39. Runaway Bride

McNear: The spiritual sequel to 1990’s Pretty Woman doesn’t capture the original’s lightning-in-a-bottle chemistry, but Julia Roberts, as a small-town charmer with a history of breaking off engagements at the altar, and Richard Gere, as a reporter sent to write about her, still deliver a perfectly pleasant rom-com.

How did this movie influence films to come? Consider this scene in which Joan Cusack’s Peggy breaks the news to Julia Roberts’s Maggie that she is a Manic Pixie Dream Girl (before the term existed): Charming but mysterious; quirky but not weird; and, above all, incapable of turning off her amorphous, offbeat vulnerability, which draws men in like moths. The MPDG archetype was about to become a dominating force of aughts cinema: Garden State in 2004, The Last Kiss in 2006, 500 Days of Summer in 2009, and Elizabethtown, a 2005 review of which coined the “Manic Pixie Dream Girl” term. Runaway Bride didn’t invent the MPDG—see Tiffany’s, Breakfast at—but the perpetually enchanting, moony-man-zapping Maggie delivered us about as clear a mission statement as we had up to that point.

What’s the one thing about this movie that’s aged the worst? As a person who writes words for a living, I’m tempted to say the depiction of journalism, in which a USA Today relationships columnist is the kind of New York City celebrity who gets hollered at by construction workers, and who can afford a grandiose apartment with a terrace overlooking Central Park. But realistically, it’s the underlying grossness of the journalistic premise that sparks the inevitable romance: The first column Gere’s Ike writes about Maggie is a gadfly recounting of her supposedly seven engagements (it’s only four!) in which he didn’t even speak to her; “Boy, she gets around” is a pitch that multiple editors apparently found both inoffensive and newsworthy. Hall & Oates’s “Maneater” plays as his convertible rumbles into town. I’d be mad, but it really is a jam.

38. The Limey

Ryan: The Limey is a very simple noir revenge tale, told in broad daylight in a very complicated way. You can love it for avenging angel/devil Terence Stamp screaming, “TELL THEM I’M FUCKING COMING” at a fleeing group of goons, in blistering Cockney, but Steven Soderbergh is the real killer on the loose here.

How did this movie influence films to come? It certainly influenced Soderbergh movies to come. You can see the elliptical editing style and the non-linear storytelling in his trio of early 21st century classics—Erin Brockovich, Traffic, and Ocean’s Eleven. Soderbergh would later return to the milieu of The Limey with another movie written by screenwriter Lem Dobbs: the espionage actioner Haywire.

Who stole this movie? The Limey has the kind of stellar ensemble you’d expect from a Soderbergh movie, with great supporting turns from Luis Guzmán, Lesley Ann Warren, Nicky Katt, and cult film icon Barry Newman. But Peter Fonda almost walks away with this entire thing.

The Easy Rider star plays an L.A. record producer who moonlights as a drug trafficker, living a life of sin, luxury in the Hollywood Hills.

37. All About My Mother

Kate Knibbs: Pedro Almodóvar’s winking, melodramatic love note to actresses, Tennessee Williams, and Barcelona is one of those movies that balances the sad and joyful in just the right proportion.

How did this movie influence films to come? All About My Mother features several prominent trans characters and is very much focused on the idea of performing and inhabiting gender; its success was an early sign that films that explore gender identity could find a wide audience.

Who stole this movie? Penélope Cruz is so beautiful in this movie that it’s almost physically painful to watch her performance. This was the first film I saw with Cruz in it, and I remember watching it for the first time and thinking that I’d laid eyes on the most captivating living thing in existence.

36. Analyze This

Lindbergh: 1999 was a watershed year for fictional mafiosos in therapy. A few months after the world was introduced to Tony Soprano—who later inspired this movie’s warmed-over sequel, Analyze That—Robert De Niro blended his penchant for playing intimidating mobsters with his history of occasional comedic diversions in the person of Paul Vitti, made man and murderer prone to panic attacks and ED.

How did this movie influence films to come? Along with 2000’s Meet the Parents, Analyze This touched off a De Niro comedy boom that hasn’t abated. The results have ranged from forgettable to face-palm-inducing. De Niro is a gifted comic actor, and in the hands of Harold Ramis, playing opposite Billy Crystal and working with a solid, sitcom-y setup (for one movie, but not multiple movies), he brought just the right degree of self-caricature to the role. On its own, Analyze This was a worthy entry in De Niro’s late-career canon, but its success probably partly enabled (and thus bears at least some of the blame for) Showtime, The Big Wedding, and Dirty Grandpa. That’s a lot to atone for.

How did this movie change popular culture? It gave an army of fair-to-middling De Niro impersonators a second delivery to mimic that was just as recognizable, less threatening, and even easier to replicate than “You talkin’ to me?”

The movie was frivolous fun, even if it makes you feel a little bad about pulling for the personal empowerment of a homophobic, misogynistic killer. But “You—you’re good,” with the finger wag and the crooked grin? That’s a timeless staple of the De Niro knockoff repertoire.

35. The Wood

Donnie Kwak: A more wholesome (and much blacker) version of American Pie, The Wood follows three Inglewood friends who make a high school pact on who will lose his virginity first. This is a comfort-food movie, predictable but satisfying. Also, by jumping between the late ’80s and the late ’90s, the film offers a treasure trove of old-school music.

What’s the one thing about this movie that’s aged the worst? The New York Times review mentions how “the physical continuity between the characters as adolescents and their older selves requires some suspension of disbelief.” Case in point: believing that high-school Alicia (Malinda Williams, born 1970) will somehow grow into Sanaa Lathan (born 1971) as an adult. Also: Young Slim’s Jheri curl wig.

Who stole this movie? Sean Nelson, a.k.a. the kid in Fresh, anchors The Wood with an emotionally grounded, heartfelt performance. It boggles the mind that he’s only appeared in a handful of films since.

34. The Green Mile

Lindbergh: As Oscar-nominated 1990s cinematic period pieces set inside penitentiaries, based on Stephen King stories, directed by Frank Darabont, scored by Thomas Newman, and starring 6-foot-5 lead actors go, The Green Mile is second only to The Shawshank Redemption. It was a bigger box office success, though, and remained the highest-grossing King adaptation until It took the top spot in 2017.

What is the best behind-the-scenes anecdote about this movie? King was thrilled with the casting of Tom Hanks as Cold Mountain guard Paul Edgecomb, but according to King scholar George Beahm, the author’s first choice to play John Coffey was Shaquille O’Neal. Going from Kazaam and Steel to Oscar bait like The Green Mile would have been an incredible career pivot for Shaq, but although Shaq had the height, his screen test probably wouldn’t have looked like Michael Clarke Duncan’s. Coffey’s character garnered criticism from Spike Lee, but Clarke Duncan earned his Oscar nomination by making every scene that featured him a tearjerker.

Who stole this movie? Mr. Jingles the mouse. Mr. Jingles’s death and resurrection scene is one of the movie’s most affecting, and while that had something to do with Clarke Duncan, it wouldn’t have worked without the audience’s attachment to the talented mouse. It took more than 30 mouse performances to bring Mr. Jingles to life, although fortunately it took only an animatronic mouse and some CGI to briefly bring him to death. The various Messrs. Jingles were rewarded with food for hitting their marks, and the naturalism of their performances likely stemmed in part from their utter unawareness that they were acting at all.

33. Varsity Blues

Knibbs: Varsity Blues uses all the trappings of the typical football movie—a tragic injury, a goofy linebacker, and a Big Final Game—but does so with a sly and surprisingly biting attitude towards our national sport.

How did this movie change popular culture? Well, 20 years later, you can go on the internet and find recent how-to items like this: “6 Ways to Recreate the Varsity Blues Whipped Cream Scene Tonight.”

What is the best line or moment from this movie? Backup quarterback-turned-reluctant star quarterback Mox’s surly thesis statement, drawled at his father: “I don’t want your life.” It’s an iconic line reading from James Van Der Beek, for starters, but it also neatly encapsulates what distinguishes Varsity Blues from the typical sports movie—it mostly calls bullshit on the idea that high school sports stardom means much of anything. While the climax does feature Mox leading the team to victory, he reveals in a voiceover that he never played football again afterwards, and happily went to college a non-athlete. The movie’s coach doesn’t inspire, he’s a villain, and the hero worship of the town is myopic, not quaint.

32. Dogma

Knibbs: Dogma could only be the work of someone who genuinely loved going to Mass stoned absolutely out of his gourd, and I mean that as a compliment to Kevin Smith. For a movie that stirred up so much controversy, Dogma is actually pretty gentle satire.

What’s the one thing about this movie that’s aged the worst? Well, you can’t watch Dogma on any streaming service, which is definitely something that doesn’t work in 2019—and the reason why is because the Weinsteins personally own the movie. Here’s Kevin Smith’s explanation of what went down:

Considering that Harvey Weinstein lost power in Hollywood after investigative reporting detailed his predatory and abusive behavior toward women and that he is currently awaiting criminal trial for sexual assault, the likelihood of the Weinsteins prioritizing the digital release of Dogma is … low.

Who stole this movie? Alanis Morissette as God. I’m not sure why Morgan Freeman keeps getting to play God when Alanis is right there.

31. Summer of Sam

Nayman: Ten years after Do the Right Thing, Spike Lee conjured up another sweltering New York City summer, using the 1977 Son of Sam murders as the backdrop for a scorching melodrama about childhood friends—played by John Leguizamo and Adrien Brody—whose relationship reaches an emotional boiling point.

What is the best behind-the-scenes anecdote about this movie? There’s a palpable and unpleasant tension running throughout Summer of Sam, and it’s arguably tied to its chaotic production. Lee encouraged his actors to improvise, which led to John Leguizamo spitting on Mira Sorvino without her prior knowledge. The latter also complained about filming an orgy sequence, calling the experience demoralizing (the scene itself had to be partially cut to avoid an NC-17 rating). Brody, whose flamboyant performance is the movie’s highlight, had his nose broken while shooting a scene where his character is attacked by an angry mob. Idina Menzel, who’d been cast as Brody’s girlfriend, had all her footage cut. It doesn’t sound like anybody had fun, least of all Lee, whose next film, Bamboozled, was produced on a much smaller and more independent scale.

How did this movie influence films to come? No stranger to controversy, Lee came under scrutiny from the family members of some of David Berkowitz’s victims, who feared that a movie about the “Son of Sam” would, however indirectly, glorify the serial killer and his work. Lee heard their complaints, and the result was a slightly tweaked screenplay that focused more on the community and its reaction to the murders, eschewing thriller tropes (and gore) for a more panoramic sociological approach (including a cameo by journalist Jimmy Breslin, a key reporter on the case, playing himself as a kind of Greek chorus). You can see traces of Lee’s template in David Fincher’s Zodiac, which also deals more with the fallout from a killer’s reign of terror than the killer himself.

30. She’s All That

Juliet Litman: You know the drill: Freddie Prinze Jr. makes a bet with Paul Walker that he can turn Rachael Leigh Cook—who is hideous because she does art and wears glasses, of course—into prom queen. What ensues is a late ’90s teen movie classic. Also, Usher DJs.

What is the best line or moment from this movie? She’s All That is filled with enough memorable scenes that it could be mistaken as the ur-teen movie. There’s the epic house party in which Taylor (Jodi Lyn O’Keefe) and Laney (Rachael Leigh Cook) get in a fight, and Taylor delivers an exegesis that reinforces the social order as high schoolers know it. There’s the cafeteria scene in which Zack (Freddie Prinze Jr.) defends Simon’s (Kieran Culkin) honor by making a bully eat pizza with pubic hair on it. There’s the inexplicable dance scene at the prom in which the senior class busts out a fully choreographed number that everyone knew. There’s every moment in which Usher appears as the in-house DJ. But only one scene in the movie was soundtracked by Sixpence None the Richer’s essential one-hit wonder, “Kiss Me.” Midway through the movie, Cook descends her staircase to reveal that all she needed was a pixie haircut, a red halter dress, and platform heels to capture the cool-but-secretly-smart jock’s attention. It instantly landed in the annals of great movie makeovers, and the gravity the moment not only forced Laney Boggs to stumble into Zack Siler’s arms, it also knocked over an army of teens who fell for the movie.

Who stole this movie? Paul Walker may be most famous for the Fast and Furious franchise, and he may have broken through because of Varsity Blues, but beefy and evil Paul Walker shines brightly in She’s All That. As Dean Sampson, Walker is a perfect foil for Freddie Prinze Jr. because he’s equally handsome and charming. Only the best teen movies deliver a villain worthy of the hero, and the importance of Paul Walker is overlooked to this effect.

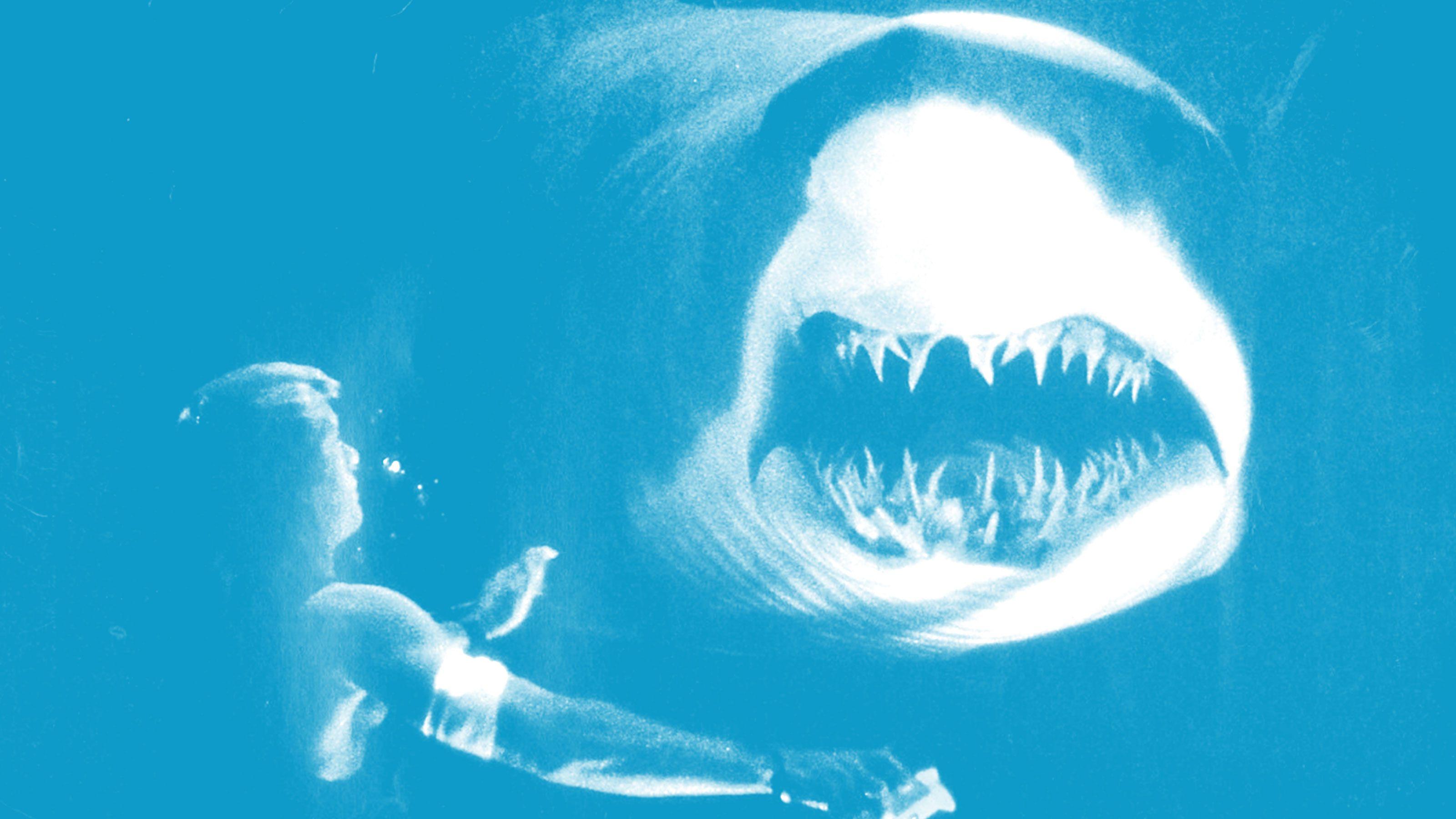

29. Deep Blue Sea

Knibbs: “Genetically engineered sharks want to kill everyone” is the perfect premise for an unabashedly campy B-movie, which is probably why this is the finest unabashedly campy B-movie of the ’90s.

What is the best line or moment from this movie? There is only one answer to this question—when Samuel L. Jackson’s character gives a rousing, inspirational speech and then gets immediately and unexpectedly gobbled up by a super-smart shark.

That is the best behind-the-scenes anecdote about this movie? Test audiences had such an intense reaction to the movie’s original ending that they changed it at the last minute. The pompous British scientist played by Saffron Burrows originally survived, but in the version that made it into theaters, she dies in the final scenes. “What had happened was that the audience felt so deeply that the scientist character, the woman who was behind the whole experiment with the sharks, that it was all her fault. In their minds, she was the bad guy, and in our minds, she was the heroine and we thought saving her was the key. Basically, we had test cards that said ‘Kill the bitch.’ It was an amazing revelation,” director Renny Harlin told Crave Online in 2013. “I remember us all sitting down and going, Holy shit, we are in trouble. How do we fix this? It was my idea, I said, ‘OK, we don’t have time for a big reshoot but I have an idea. When she falls in the water, what if she doesn’t survive? She gets eaten by the sharks and LL Cool J is the hero. Everybody likes him, and Thomas Jane.’”

28. Jawbreaker

Herman: Heathers, meet the ’90s.

What is the best behind-the-scenes anecdote about this movie? When Julie Benz is sobbing during the oh-shit-we-murdered-our-friend car freakout scene, she’s not (just) acting: Rose McGowan had convinced her to chop all her hair off right before filming, much to the actress’s instant regret. Benz drew on that real-life anguish for inspiration.

What is the best line or moment from this movie? A queen bee movie lives and dies on its slo-mo strut scenes (see, most recently, Assassination Nation). This is the one to beat.

27. Boys Don’t Cry

Alyssa Bereznak: Despite being one of the first major films to grapple with being transgender in America, Boys Don’t Cry is neither self-congratulatory, heavy-handed, nor exploitative. Credit goes to director Kimberly Peirce, who focuses her unwavering lens on the real-life tragic love story of Brandon Teena (Hilary Swank) and Lana Tisdel (Chloë Sevigny), and treats it with humility and respect—even when the world they inhabit does not.

How did this movie influence films to come? Boys Don’t Cry’s nuanced exploration of gender identity was so largely misunderstood in Hollywood that agents were reportedly wary of sending their clients to audition for the role of Brandon, and it was initially given an NC-17 rating, necessitating several cuts. The movie unquestionably paved the way for more stories like Brandon’s to be told, even if there are still too few projects like it today.

What’s the one thing about this movie that’s aged the worst? The reviews. As you might expect, many a legacy publication glibly wrote off both Brandon’s story and Peirce’s accomplishments as a filmmaker. Some lowlights include New York magazine’s Peter Rainer—“the film could have used a tougher and more exploratory spirit; for Peirce, there was no cruelty, no derangement in Brandon’s impostures toward the unsuspecting”—and Time’s Richard Corliss: “Teena Brandon blew into town, stuck a sock in her crotch and said she was a guy: Brandon Teena.”

26. American Beauty

Zoladz: Few Best Picture winners of the past few decades have aged as poorly as this one—even at the time it felt like a subpar representative for such an inventive year in American film. But, for better or worse, this rose-petal-strewn exploration of suburban American malaise has made an indelible mark on pop culture.

What’s the one thing about this movie that’s aged the worst? Say it with me, friends: KEV-IN SPA-CEY.

How did this movie change popular culture? From Family Guy to Katy Perry’s “Firework,” never again was a plastic bag just a plastic bag.

Come back Tuesday to see The Ringer’s top 25 movies of 1999.