fSometimes, during their breaks, the men who worked alongside Chuck Palahniuk would gather to talk about where their lives had gone wrong. It was the early nineties, and Palahniuk was employed at a Portland, Oregon, truck-manufacturing company called Freightliner. Many of his colleagues were well-educated, underutilized guys who felt out of sorts in the world—and they put the blame on the men who’d raised them. “Everybody griped about what skills their fathers hadn’t taught them,” says Palahniuk. “And they griped that their fathers were too busy establishing new relationships and new families all the time and had just written off their previous children.”

Palahniuk’s Freightliner duties included researching and writing up repair procedures—tasks that required him to keep a notebook with him at all times. At work, when no one was looking, he’d jot down ideas for a story he was working on. He’d continue writing whenever he could find the time: between loads at the laundromat or reps at the gym or while waiting for his unreliable 1985 Toyota pickup truck to be fixed at the auto shop. The result was a series of “small little snippets” about an unnamed auto company employee who’s so spiritually inert, so unsatisfied, that he finds himself attending various cancer support groups, just to unnumb himself. He soon succumbs to the atomic charisma of Tyler Durden, a mysterious figure whose name had been partly inspired by the 1960 Disney movie Toby Tyler. “I grew up in a town of six hundred people,” says the Washington-born Palahniuk, “and a kid in my second-grade class said he’d been the actor in that movie. Even though he looked nothing like him, I believed him. So ‘Tyler’ became synonymous with a lying trickster.”

After meeting Tyler Durden, Palahniuk’s narrator begins attending Fight Club, a guerrilla late-night gathering in which men voluntarily beat each other bloody. Fight Club comes with a set of fixed rules, the most important of which is that, no matter what, you do not talk about Fight Club. Many of the book’s brawlers are working-class guys with the same dispiriting jobs—mechanics, waiters, bartenders—held by some of Palahniuk’s friends. “My peers were conflict averse,” says Palahniuk. “They shied away from any confrontation or tension, and their lives were being lived in this very tepid way. I thought if there was some way to introduce them to conflict in a very structured, safe way, it would be a form of therapy—a way that they could discover a self beyond this frightened self.”

Palahniuk would bring work-in-progress chapters to writing classes and workshops around Portland, holding one successful early reading at a lesbian bookstore. “They wanted to know ‘Is there a women’s version of this?’ he says. “They just assumed Fight Clubs existed in the world and wanted to participate.” Palahniuk, then in his early thirties, had recently seen his first novel get rejected. “I was thinking ‘I’m never getting published, so I might as well just write something for the fun of it.’ It was that kind of freedom, but also that kind of anger, that went into Fight Club.” He’d wind up selling the book to publisher W. W. Norton for a mere $6,000.

Fight Club’s quiet 1996 release came just a few years after the arrival of the so-called men’s movement, in which dissatisfied dudes looking to reclaim their masculinity would gather for all-male retreats in the woods. They’d bang drums and lock arms in the hope of escaping what had become a “deep national malaise,” noted Newsweek. “What teenagers were to the 1960s, what women were to the 1970s, middle-aged men may well be to the 1990s: American culture’s sanctioned grievance carriers, diligently rolling their ball of pain from talk show to talk show.”

Palahniuk’s Fight Club characters, though, were younger and angrier than their aggrieved elders. A few primal scream sessions in the woods weren’t going to cut it. “We are the middle children of history, raised by television to believe that someday we’ll be millionaires and movie stars and rock stars, but we won’t,” Tyler says of his peers, adding “Don’t fuck with us.” It was one of many briskly written yet impactful mission statements in Palahniuk’s book, which earned positive reviews from a few major critics—the Washington Post called it “a volatile, brilliantly creepy satire”—as well as the author’s own father. “He loved it,” Palahniuk says. “Just like my boss thought I was writing about his boss, my dad thought I was writing about his dad. It was the first time we really connected. He’d go into these small-town bookstores, make sure it was there, and brag that it was his son’s book.”

Fight Club wasn’t an especially big performer in its original hardcover run, selling just under 5,000 copies. But before it even hit shelves, an early galley copy reached producers Ross Grayson Bell and Joshua Donen, the latter of whom had produced such films as Steven Soderbergh’s noir The Underneath. Bell was put off by some of the book’s violence, but as he read further, he arrived at Fight Club’s big revelation: the insomniac narrator, it turns out, really is Tyler Durden, and at night he’s been unknowingly leading the Fight Club army raiding liposuction clinics for human fat—first to turn into soap, and then to use for explosives. Eventually Tyler’s hordes of followers begin engaging in a series of increasingly violent acts. “You get to the twist, and it makes you reassess everything you’ve just read,” says Bell. “I was so excited, I couldn’t sleep that night.” Looking to make Fight Club his first produced feature, Bell hired a group of unknown actors to read the book aloud, slowly stripping it down and rearranging parts of its structure. He sent a recording of their efforts to Laura Ziskin, who’d produced Pretty Woman and was now heading Fox 2000, a division that focused on (relatively) midbudget films. According to Bell, after listening to his Fight Club reading during a fifty-minute drive to Santa Barbara, Ziskin hired him as one of Fight Club’s producers. “I didn’t know how to make a movie out of it,” said Ziskin, who optioned the book for $10,000. “But I thought someone might.”

Ziskin gave a copy of Palahniuk’s book to David O. Russell, who declined. “I read it, and I didn’t get it,” Russell says. “I obviously didn’t do a good job reading it.” There was one filmmaker, though, who definitely got Fight Club. He was the perfect match—a guy who viewed the world through the same slightly corroded View-Master as Palahniuk; who could attract desirable actors; who could make all of Fight Club’s bodily fluids splatter beautifully across the screen. And he wasn’t afraid of drawing a little blood himself.

“I grew up in a particularly weird place and time,” says David Fincher. He was raised in Marin County in San Francisco in the sixties and seventies, right as the area was being invaded by autonomy-seeking young filmmakers looking to flee Los Angeles. It wasn’t unusual for residents to catch a glimpse of George Lucas—“he was the rich neighbor up the street who’d bought the house and restored it impeccably”—as well as big-studio directors such as Michael Ritchie and Philip Kaufman. “None of the kids in my neighborhood wanted to be doctors or lawyers,” Fincher adds. “They all wanted to be moviemakers.”

So did Fincher, who began taking film classes as far back as elementary school—which was also right around the time he discovered an aversion to bureaucracy. And authority. And unquestioned rules of any kind. “Even at a very early age,” he says, “I didn’t understand why you didn’t have any say in your curriculum. Because I just wanted to make movies, and I didn’t understand why they wanted me to learn all of this other shit. And I had parents who were very much about pushing authority. They didn’t want their kid to be taken advantage of.” Fincher’s father was a journalist and author, while his mother was a mental health nurse who worked in a methadone clinic; they often discussed their jobs with their young son. “My parents didn’t keep much from me,” he says. “They were like, ‘Here’s the world you’re going out into.’ ”

In the early eighties, Fincher skipped college and went to work for the rich guy up the street, taking a job at the Lucas-owned Industrial Light & Magic—where he helped out on Return of the Jedi—before directing an incendiary commercial for the American Cancer Society featuring a lifelike puppet fetus puffing on a cigarette. Made for just a few thousand dollars, the ad was a black-humored homage to the spectral “Star Child” of 2001: A Space Odyssey, and it brought on the first controversy of Fincher’s career: major networks refused to run the spot, while tobacco companies objected to its bluntness.

Fincher would go on to direct several more commercials, eventually entering the world of music videos, where he’d make some of the most rewind-worthy entries of the eighties and early nineties: Madonna’s epic Metropolis riff “Express Yourself”; George Michael’s luxurious “Freedom ’90”; Aerosmith’s revenge noir “Janie’s Got a Gun.” Though his videos were often big hits on MTV, “people who worked in commercials and those who worked in features didn’t cross-pollinate,” says Fight Club editor and longtime Fincher collaborator Jim Haygood. “And music videos weren’t taken seriously at all.” But by the time Fincher’s sultry black-and-white clip for Madonna’s “Vogue” premiered in 1990, his videos were just as cinematic as anything else on the small screen.

The next year, Fincher was hired for his first feature: Fox’s troubled deep-space excursion Alien 3. The $56 million production had already seen one director come and go, and when the twenty-seven-year-old Fincher showed up in England for filming, the film lacked a finished script. He found himself locked in combat with executives for much of the months-long shoot, making late-night calls after a long day of filming in order to justify the next day’s shoot. The whole process, Fincher said, was akin to being “sodomized ritualistically for two years.” He all but disowned the film and despised the studio whose logo appeared before it.

After Alien 3’s disappointing reception, Fincher figured he was unemployable as a film director and returned to making commercials. It would take more than three years before the release of his next film, 1995’s Seven, a gorgeously dismal serial-killer drama with a head-snapping final twist. It became a worldwide hit, and while Fincher was editing a follow-up, the Twilight Zone–indebted thriller The Game, he got a call from Ross Grayson Bell’s producing partner, Joshua Donen, urging him to read Fight Club. “I was in my late thirties, and I saw that book as a rallying cry,” says Fincher. “Chuck was talking about a very specific kind of anger that was engendered by a kind of malaise: ‘We’ve been inert so long, we need to sprint into our next evolution of ourselves.’ And it was easy to get swept away in just the sheer juiciness of it.” Fight Club producer Ceán Chaffin notes, “I remember him reading it in galley form and laughing the whole time. It seemed like exactly the kind of movie he should be making.”

Fincher tried to buy the rights to Fight Club himself, only to find that Fox had beaten him to it. Still resentful about the Alien 3 fiasco, he had little interest in working with the studio again. But after a meeting with Ziskin, he considered returning to Fox for Fight Club—so long as he could make it in the grandest way possible. “I said, ‘Here’s the two ways you can go: you can do the $3 million version of this movie and make it on videotape and make your seditious little sharp stick in somebody’s eye.’” But the real “act of sedition,” he told the studio, would be to invest tens of millions of dollars “and to put movie stars in it and get people to go and talk about the anticonsumerist rantings of a schizophrenic madman.” Fox agreed to give Fincher some time to put together a script and a cast, to see if there was any way to make Fight Club a reality. “It was a dark little book—not exactly the kind of fodder for a movie,” says Bill Mechanic, then the studio’s chairman. “I thought it would never see the light of day.” (As for Fight Club’s author, he had no idea who Fincher even was: “I hadn’t been to the movies since I was in college in the early eighties,” says Palahniuk. “I’d become really annoyed with people’s behavior in theaters.”)

To Fincher, Fight Club was heir to The Graduate, another tale of a distressed young man pushing back against an older generation’s expectations. In Fincher’s mind, “we were making a satire. We were saying ‘This is as serious about blowing up buildings as The Graduate is about fucking your mom’s friend.’ ” A copy of Fight Club would even be sent to Graduate screenwriter Buck Henry, to see if he’d be interested in taking a crack at the adaptation. (Henry’s response, according to Fincher: “I don’t think there’s anything funny about it.”) Instead, the job went to Jim Uhls, who’d spent much of the nineties “getting hired to write things that didn’t get made,” he says. Palahniuk’s book had resonated deeply with Uhls, who’d worked for five years as a bartender before selling his first script. “I knew what it was like to have a bullshit job,” Uhls says. “It affected how you felt about yourself, in a masculine way. And after I read Fight Club, my jaw was on the ground for two weeks. But I was also bracing myself: ‘It will be fun to write this, but it’s never going to be made.’ ”

After a “marching orders” meeting with Fincher and Bell, Uhls began work on a Fight Club script. “The book had a billion wonderful things in it, but you can’t put them all in,” says Uhls. One of the screenplay’s biggest innovations was the finale, in which Tyler Durden and his anonymous followers—dubbed “space monkeys”—take down the credit card companies in order to create what Tyler calls “economic equilibrium.” It had come out of conversations between Uhls and Bell, the latter of whom was broke and living off credit cards. He’d watched as debt levels soared around the world in the nineties, in part because of global deregulation. At the same time, a midnineties Supreme Court decision had freed up credit card companies to enact record-high late fees. By the end of the decade, millions of people were feeling overleveraged. “I said, ‘What if they blow up the credit card companies, and everybody woke up one day and they didn’t have to pay their bills?’ ” remembers Bell. “We needed something where the audience members would cheer the destruction of the world.”

They also needed a movie star who could pull off that destruction with charm: Brad Pitt. The actor had become one of the decade’s few newly anointed movie stars, having portrayed an emo bloodsucker in Interview with the Vampire, a tic-ridden loon in the Oscar-nominated 12 Monkeys, and a newbie cop in Fincher’s own Seven. One night in the summer of 1997, Pitt was returning to an apartment in New York City—having worked a long day on the somnambulant drama Meet Joe Black—when the director met him outside with a copy of the Fight Club script. The actor was tired, but Fincher promised him that it would be worth staying up for a bit.

Pitt was thirty-three years old at the time, unfathomably sculpted and uncannily cool, which made him well suited to play the coarsely charming Tyler Durden, who seduces Fight Club’s narrator, at least philosophically, with salvos such as “The things you own end up owning you.” On the night the two men first hang out, Tyler convinces the narrator to do him a favor—“I want you to hit me as hard as you can”— that quickly leads to a bond-building fistfight in a bar parking lot. Tyler is Friedrich Nietzsche’s Übermensch, only somehow more über: He drives a stolen convertible, has epic sex with a theatrically suicidal chain-smoker named Marla, and somehow makes giant red-tinted sunglasses look cool.

Even though Pitt had been marquee-name famous for much of the decade and was dating Friends star Jennifer Aniston—who’d personally shave Pitt’s head for his Fight Club role—he could relate to the movie’s existential uncertainty. “I’m the guy who’s got everything,” he said at the time. “[But] once you get everything, then you’re just left with yourself. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: It doesn’t help you sleep any better, and you don’t wake up any better because of it.”

Fincher wouldn’t find the right actor to play Fight Club’s impressionable, unknowingly anarchic narrator until he watched The People vs. Larry Flynt, the 1996 porn-kingpin biopic starring Edward Norton as a guileless lawyer. “I saw him deliver the speech before the Supreme Court, and I was like, ‘That’s the guy,’ ” says Fincher. “Because this character needs a kind of verbal diarrhea.” He also recognized a unique malleability. “Edward’s ultimately kind of a blank slate,” said Fincher at the time. “His opacity is part of the thing that makes him a terrific Everyman.”

Norton, in his late twenties, was a Yale-educated theater actor who’d earned an Oscar nomination for his first film role, playing a murderer posing as a simpleton in Primal Fear. “I was lucky in the sense that I kind of had one of those zero-to-sixty moments,” says the actor. “I didn’t go through a phase where I felt like I should take anything that came my way. I had the luxury of choosing, and though I had lots of sort of commercial stuff coming at me after Primal Fear, none of it was particularly compelling to me.” Instead he opted for a series of wildly dissimilar films, including a Woody Allen musical (Everyone Says I Love You); a crackling, seventies-indebted cardshark-noir (Rounders); and a seering neo-Nazi drama (American History X).

Norton read Fight Club in one sitting; like Fincher, it reminded him of The Graduate, albeit updated for the end of the twentieth century. “It took aim right at what a lot of us were starting to feel,” says Norton. “The book was so sardonic and hilarious in observing the vicissitudes of Gen-X/Gen-Y’s nervous anticipation of what the world was becoming— and what we were expected to buy into.” When he first talked to Fincher about Fight Club, Norton says, “I said, ‘You’re going to do this as a comedy, right?’” And he was like, ‘Oh, yeah—that’s the whole point.’ ”

For weeks, Norton, Pitt, and Fincher would meet with Andrew Kevin Walker, who’d written Seven and revised parts of Uhl’s script: “He made this amazing chair, and I came and sanded some of the edges and maybe put the little things that protect the floor on the bottom,” says Walker. They’d hang at Pitt’s house or at an office across from Hollywood’s famed Grauman’s Chinese Theatre, where they’d drink Mountain Dew, play Nerf basketball, and talk for hours, riffing on the film’s numerous bull’s-eyes: masculinity, consumerism, their aggravating elders. “We were sitting around, thinking of all the things we wanted to stick a fork [into],” says Norton, who was especially irked by the recent revival of the Volkswagen Beetle, an icon of the flower-power era that was being targeted to younger drivers. “They just wanted to repackage an authentic baby boomer youth experience to us—they don’t even want us to have our own,” he says, laughing. “They just want us to buy sentiment for the sixties, with a little fucking molded flower that you sit in the dashboard. And they wonder why we’re cynical.” As they lined up their targets and worked on the script, the actors and filmmakers were “breaking apart every line like it was Shakespeare,” said Pitt. “It’s such a hard film to get a handle on. How do you characterize something you’ve never seen before?”

Throughout their conversations, all four contributed ideas to a long spiel they dubbed “a Mamet rant”—“as if to aspire to the greatness of David Mamet,” says Walker. “It was stuff like ‘You’re not the contents of your wallet.’ ” Some of their Nerf session conversations were incorporated into a long anti–pep talk Tyler gives the narrator early on. “Fuck off with your sofa units and green stripe patterns,” he tells him. “I say: Never be complete. I say: Stop being perfect.”

After working to put together Fight Club for months, “I went back to Fox with this unabridged dictionary-sized package,” remembers Fincher. “ ‘It’s Edward. It’s Brad. We’re going to start inside Edward’s brain and pull out. We’re going to blow up a plane. All this shit. You’ve got seventy-two hours to tell us if you’re interested.’ And they said, ‘Yeah, let’s go.’ ”

Holt McCallany could always tell if he was stuck in a bad movie. “You know when you’re making a turkey,” says McCallany, who began acting in the mideighties. “You’re like, ‘God, why did I agree to do this? Can I give back the money? Can I claim an injury? Maybe fake a death in the family or a heart attack?’ And there are times when you’re equally sure you’re part of something very special. That was the case on Fight Club.”

Fincher had cast McCallany as “the Mechanic,” one of the legions of unnamed bruisers who join Tyler’s underground movement, taking up residence in the group’s dilapidated headquarters—dubbed the Paper Street House—and aiding him in his acts of urban menace. McCallany was particularly well suited for the role: he’d worked with Fincher on Alien 3 and had trained in mixed martial arts. Perhaps more important, McCallany, then in his midthirties, could relate to Fight Club’s sense of existential displacement. “Think about our grandfathers’ generation,” he says, “and what that must have meant to go to World War Two and fight this epic battle against this consummately evil adversary. And to return to your homeland in victory and prosperity and to see the gratitude of your friends and your family and the brotherhood that you shared. You’d carry that with you the rest of your life. But for us younger guys kicking around in 1999, we didn’t have any of that. What are we supposed to do? Get a one-bedroom apartment and furnish it at IKEA?”

He wasn’t alone in his frustration. In the fall of 1999, the journalist Susan Faludi published Stiffed: The Betrayal of the American Man, in which she interviewed everyone from gang members to shipyard employees to even Sylvester Stallone to suss out the root causes of America’s “crisis of masculinity.” One possible cause: a postwar emphasis on consumerism and vanity. The modern man, Faludi wrote, has been sold the idea that masculinity is “something to drape over the body, not draw from inner resources; that it is personal, not societal; that manhood is displayed, not demonstrated.”

Or, as Tyler Durden might put it: “Advertising has us chasing cars and clothes, working jobs we hate, so we can buy shit we don’t need.” It’s part of a speech he gives halfway through Fight Club, standing in a dank bar basement surrounded by several young men—including McCallany’s “Mechanic”—who will soon be brawling in order to feel . . . anything.

Before filming the downstairs fisticuffs, cinematographer Jeff Cronenweth lit the room with “budget busters”—little clip-on lights that could be picked up at Home Depot. “We’d age them down and put them right in the shot,” says Cronenweth, “because that’s what these guys would have done, in their rudimentary way, to make their spring-up club.” The Fight Club set, he says, “wasn’t just a basement— it had character and a texture you could almost touch: the smoke, the dripping water, the aging, the points of light leaking through.”

There was also, of course, a good amount of blood. Before filming, Fincher and the cast had studied tapes featuring the low-budget, frills-free brawls put on by Ultimate Fighting Championship, a company launched in the early nineties. “It was so raw,” Fincher said. “You see someone get hit with the palm of somebody else’s hand, and their nose just moves over like an inch and a half across their face.”

Pitt and Norton both took boxing and tae kwon do classes before filming. But in order to play the scrawny, creature-comforted office drone who imagines himself as god-among-men Tyler Durden, Norton couldn’t look as jacked as he’d been in American History X. “I was supposed to be becoming the junkie version of the personality, and he gets to be Tyler, the Adonis,” Norton says of his costar. “Brad is the most annoying genetic miracle in the world. We were in Stage 16 at [the Fox lot]. It was one of the biggest soundstages I had ever been in, and the craft service table ran the full length of it. And on the film where I was trying to starve myself, Brad would eat six hot dogs and half of a pumpkin pie, and only get stronger and younger while I remember just sipping my hot tea. The truth is, we probably spent more time learning to make soap than we did training for anything.” (The actors had, in fact, worked with an expert soap maker before filming.)

As a result, much of the combat in Fight Club feels sloppily forceful— the handiwork of men taking their very first swings at life. The Fight Club set was “a hypermasculine environment,” says McCallany. “You’re talking about a film set that has forty dudes on it every day and no women.”

But there was one woman caught up in Fight Club: Marla, the acidic, cigarette-devouring schemer who gets wrapped up with the narrator, unaware of his lunacy. Several actors had been considered for the role, including Courtney Love, who was dating Norton at the time. “Courtney totally understood the character—there was no fucking doubt about that,” says Fincher. “She got the pathos of it.” Ultimately, though, “I felt their personal stuff would get in the way of the work. And there was a lot of work.”

At one point Pitt had encouraged Fincher to watch The Wings of the Dove, the 1997 adaptation of the Henry James novel starring Helena Bonham Carter. She’d received an Oscar nomination for the film, one of many regal English historical dramas in her filmography. Carter wasn’t the obvious choice for the bilious, scheming Marla, but Fincher found her “exquisitely emotional” in Dove and sent her the screenplay for Fight Club. The script offended some of those in Carter’s orbit, including her own mother. “Mum put the script outside her bedroom, because it was a pollutant!” the actor said. “I didn’t get it when I first read it, either. I thought, ‘This is weird. Is this message particularly life-enhancing?’ ”

She met with Fincher at a Four Seasons in Los Angeles—“just to ascertain that he wasn’t a complete misogynist,” she said—before writing the director a long fax, outlining her reservations. “I just said, ‘I’ve got to play it with a big heart.’ Marla had to have a heart, otherwise she’d be just a nightmare. I was talking myself into it. By the end of the letter I’d convinced myself to do it.” Notes Norton: “Helena is so funny. In British theater, if you break [character] laughing, they call it ‘corpsing.’ And she was the absolute worst. She couldn’t get through a take without breaking up. It was like, ‘You know, Fincher’s already going to do forty of these takes—do you really want to make it seventy?’ ”

After being cast, Bonham Carter called Fight Club costume designer Michael Kaplan, who’d created the future-shocked styles of Blade Runner, as well as Flashdance’s shoulder-baring sweats. “Helena said, ‘Who the fuck is Marla Singer? You’re going to have to help me with this one,’ ” remembers Kaplan. “My response was ‘Think Judy Garland for the millennium. Not the actress in The Wizard of Oz—think Judy Garland later on, when she was a bit of a mess, drinking and doing drugs while her life was falling apart.’ ” Marla’s look is that of a desperate yet still self-respecting thrift store scavenger, with a wardrobe that includes wide-brimmed vintage hats and an old bridesmaid dress.

That same low-budget aesthetic also applied to Tyler Durden, Pitt’s swaggering, hallucinatory megamale. “David is the prince of black and gray,” says Kaplan, who worked with the director on Seven. “But on this, he said, ‘Just this once, Michael, you can’t go too far with this character.’ ” Durden’s wardrobe grows louder as the movie continues: a bloodred leather jacket with busted-up buttons; a ratty bathrobe covered with cartoon teacups; a tank top featuring seventies porno-mag imagery (which Fox would frantically fuzz out at the last minute when they discovered it on the Fight Club trailers). “I could do anything with Brad, and he could sell it,” says Kaplan. Even for Durden, however, there were limits. “I still have a Polaroid of Brad wearing a tube top,” says Kaplan. “Fincher looked at it and said, ‘I know I said you can’t go too far. But you’ve gone too far.’ ”

As for the narrator’s drab nine-to-five wardrobe, Kaplan gave Norton generic, off-the-rack shirts and suits: “No style, really—clothes you’d get bored just looking at.” Norton’s character, a midlevel auto-recall coordinator who lives in a world full of Starbucks and IKEA catalogs, exists in a self-made prison, one promising maximum security. But like Lester in American Beauty or Peter in Office Space, the narrator is aching to see a world beyond his cubicle. The difference is that he abandons his job by repeatedly smashing himself in the face, throwing himself atop a glass table, and threatening to blame it all on his boss.

The filming of Fight Club’s office-life sequences, which were handled early in production, kicked off debates between Norton and Fincher that would continue throughout shooting, as the two men tried to settle on the movie’s tone. “I think Edward had this idea of, ‘Let’s make sure people realize that this is a comedy,’ ” says Fincher. “He and I talked about this ad nauseum. There’s humor that’s obsequious, that’s saying, ‘Wink-wink, don’t worry, it’s all in good fun.’ And my whole thing was to not wink. What we want is for people to go, ‘Are they espousing this?’ ” The ensuing debates often played out on set: McCallany remembers times in the which cast members stared at the floor for half an hour, while Norton and Fincher deliberated. Over the course of countless takes, though, the two men found the proper alchemy of madcap and menace. “I was doing something in one of those office moments,” says Norton, “and I looked at Fincher, like, ‘Is this what you’re thinking?’ And he goes, ‘A little less Jerry, a little more Dean.’ And I knew exactly what he meant.”

Norton worked on Fight Club for 129 days—the longest shoot of his career. On the last night of filming, he and Pitt stayed up until four a.m., listening to Radiohead’s OK Computer, the 1997 magnum opus that, like Fight Club, was a download of twenty-first-century agitation and anxieties: technology, consumerism, pop-cultural congestion. “We had them on a lot,” says Norton. “Thom [Yorke] told me a long time later that, while they were touring for OK Computer, they had Fight Club on in the bus all the time.”

But in the final moments on the Fight Club set, he and Pitt weren’t contemplating what was ahead. They were still trying to make sense of what they’d just experienced. “Brad and I were smoking a joint in the trailer, trying to remember what we had done in the early days of the film,” Norton says. “Like they were dreams we were collectively trying to remember.”

After Fight Club wrapped, Fincher and his team began assembling the film’s unsettling score and crazy rhythms—the elements that would make the movie feel all the more pummeling to audience members. To compose the film’s soundtrack, Fincher turned to the Dust Brothers, the production duo whose album credits included the Beastie Boys’ 1989 sample bouillabaisse Paul’s Boutique, as well as Beck’s 1996 deep-grooving Odelay. The Brothers—Mike Simpson and John King, both in their early thirties—had never scored a feature film before. In their early meetings with Fincher, who loved Odelay, the director pointed to Simon and Garfunkel’s folk-pop tunes in The Graduate as an example of how he wanted the movie and its music to align. He also gave the Brothers a few sonic-specific notes. “David said, much to my chagrin, that he wanted music that sounded like it was from white guys who thought they were funky but really weren’t,” says King. “I was like, ‘Thanks a lot.’ But he was being creatively honest. We didn’t have to try to deliver that—we were white guys that thought we were funky.”

King and Simpson had spent much of the late nineties in a Silverlake home studio, where they’d recorded albums by Hanson, Mick Jagger, and Marilyn Manson. It was jammed with vintage equipment— electric pianos, effects units, a Wurlitzer—all of which would be used on Fight Club. “We were going retro but using state-of-the-art samplers to make it all sound good,” says Simpson. He and King worked on separate scenes around the house, with Fincher sometimes going from room to room, listening to what the Brothers had created. For the film’s main theme, Simpson remembers, “Fincher wanted it to be like a bee is stuck in your ear. He wanted to give the audience the impulse to leave the theater before the opening credits were done.” The result was a whirling, corrosive swarm of synths and guitars—just one of several ominous grooves that would populate Fight Club. “There’s a schizophrenic quality to the music,” says King. “But perhaps that’s appropriate for the movie.”

When Fincher wasn’t checking in on the brothers at their home studio, he was in a house in nearby Los Feliz that would serve as Fight Club’s postproduction headquarters. “It was this weird abandoned mansion—kind of like the Paper Street House,” says Fight Club editor Jim Haygood, who put the film together there. “People were coming and going, lights were coming on. The neighbors thought we were shooting porn or something. I thought, ‘This is perfect.’ ” The movie’s narrative was carefully fractured, told with sporadic flashbacks, voice-over, and even a few subliminal shots of Tyler Durden popping up unexpectedly into the frame. Fight Club played like a ride-along, allowing viewers to share the narrator’s descent into madness. “David’s thing is ‘You’ve got to assume that people are smart—you want them in on it,’ ” says Haygood. “And the concept of Fight Club—certainly during the opening moments—was to just pile stuff on. The movie has this kind of tumbling energy, where it’s always falling into the next scene.”

Everyone involved with Fight Club’s postproduction had been rushing to meet the film’s scheduled release: July 16, the same date Warner Bros. had reserved for Eyes Wide Shut. One especially difficult shot had taken almost a year to complete: the destruction of the credit card companies’ headquarters, their glittering buildings collapsing in piles of smoke and glass as the narrator watches and wonders where his mind has gone. Fincher’s team of visual effects artists worked frame by frame, creating each shattered window shard, with the director regularly calling in to get updates. “I was always wondering about, if our cell phones were tapped, what the CIA would be thinking,” Fincher said, recalling their conversations. “ ‘Well, building number three is going to go down really easily.’ ”

In early 1999, Fox finally held its first screenings for studio executives. By then, Fight Club’s budget had reached nearly $65 million. It was a sizable price tag for a movie that, as Fincher had promised, amounted to a corporate-backed act of sedition. “We started to reveal to people the hand we were holding,” Fincher says. “It was not a warm and fuzzy time. It was prickly.”

Even to those who’d read Uhls’s script or watched some of the dailies, the nearly finished version of Fight Club was a shocker. It wasn’t just its nonstop mayhem that proved disturbing, though any movie that includes bomb-making goons running wild through a city—and ends with its supposed hero blowing a hole through his cheek—was bound to cause some recoil. What stuck with viewers long after Fight Club ended was the movie’s piss-taking rejection of the last half century’s worth of postwar social values. Money? Looks? Upward mobility? None of it mattered, and none of it was making you, the audience member, happy—and the makers of Fight Club knew it. Watching the movie was like getting a middle finger to the eye. “I had two reactions,” says Bill Mechanic. “One was that anything that makes you this uneasy is great. The other was that anything that makes you this uneasy is going to be a knockdown battle.”

In the weeks after Fincher first screened Fight Club, he says, the movie was seen within Fox as “a dirty joke.” But after the April 20 massacre at Columbine High School, the attitude within the studio drastically changed. “All of a sudden,” Fincher says, “it became ‘How could you?’ ” Fincher had watched as newscasts reran the scene of Leonardo DiCaprio’s trenchcoat-clad character from The Basketball Diaries shooting up a high school. If critics were going to look to popular culture as a possible culprit, Fincher’s “plutonium-filled lunchbox,” as he called Fight Club, gave off an unmissable glow. “We had guys shaving their heads and dressing in black,” Fincher says. “There was no doubt Columbine was going to spin this.”

Fight Club’s release was soon shifted from summer to mid-October—a move Fox claimed was unrelated to Columbine and instead meant to give the director a chance to reduce Fight Club’s overlong running time. But according to the Fincher, “they felt that if they had more time to work on me, they were gonna get me to tone some of the stuff down.” Instead, no substantial changes to Fight Club were made as the studio waited out its release. “Here’s the hilarity: You look back on it and go, ‘It’s not that violent a movie,’ ” Fincher says. “I felt we had been too circumspect. But you look at the time, and the people who got their knickers in a twist. Fox was right to be trepidatious.”

The studio’s decision to delay the release of Fight Club inadvertently distanced the film from one of the year’s most notably ragefilled events: Woodstock ’99. Held over the course of a long weekend in late July, the festival was marked by instances of violence, nearly all of it carried out by young men, along with several reports of sexual assault. “How many people here woke up one morning and just decided it wasn’t one of those days, and you were gonna break some shit?” asked Limp Bizkit frontman Fred Durst during the band’s chaos-causing set. “Well, this is one of those days, y’all!” Before the event ended, cars had been set ablaze, ATMs had been toppled, and an audio tower was burning as the Red Hot Chili Peppers played their closing-night set. (“Holy shit,” noted lead singer Anthony Kiedis, “it looks like Apocalypse Now out there.”) Some of the revelers were frustrated with Woodstock’s high food costs and long lines; others simply wanted to break stuff. It made Fight Club’s depiction of pent-up male frustration all the more potent.

As Fox and Fincher readied the film for its fall release, Mechanic enlisted a few studio representatives to talk up the movie in Washington, DC, where the post-Columbine pushback against Hollywood was already underway. “I thought, ‘I don’t want this to be a poster child,’ ” he says. “Our publicity people were talking about the movie to get people to understand that we weren’t making this as an invitation for people to get violent.” Yet neither he nor Ziskin attempted to alter the movie dramatically. “There was a lot of conversation about ‘What is the smart risk here?’ ” says Fincher. “But the moment that those conversations began to tread even around the perimeter of whether or not we should denude the content in any way, I could say, ‘I’m not going to be able to change X, Y, or Z about what we’re doing.’ ”

But although Fincher would be allowed to release the version of Fight Club he’d wanted to make, he had little control over the movie’s marketing—a fact that led to tension between him and the studio. “The people whose job it is to sell it were like, ‘I’m not going down with this,’ ” says the director. One Fox marketing exec essentially told the director that Fight Club was a no-quadrant film, chiding Fincher: “Men do not want to see Brad Pitt with his shirt off. It makes them feel bad. And women don’t want to see him bloody. So I don’t know who you made this movie for.” Fincher adds, “When I think of 1999, I don’t think of my feet on the chair in front of me with a sixteen-ounce cup of popcorn in my hands. I think of it mostly as a series of meetings where I would slap myself so hard, I would leave with a calloused forehead.”

Fincher had recorded a couple of faux public service announcements for Fight Club, featuring Norton and Pitt dressed in character, advising moviegoers to turn off their pagers and cell phones—adding sinister codas such as “No one has the right to touch you in your bathing suit area.” They were among Fincher’s “in-your-face assaultive” ideas for promoting Fight Club, says Mechanic. “You can’t do that in commercial advertising—I don’t know who that gets the message to. But at the same time, nothing we did was working.” Fox’s approach was to play up the aggro aspects of Fight Club, advertising the film during wrestling matches. “I remember thinking ‘The movie’s a little homoerotic. Are you sure you guys want to do this?’ ” says Fincher. “But by that time no one was talking to me.” Adds Bell, “The publicity shots that went out were Brad bare-chested, bleeding, ready to fight. They could have done university screenings at midnight or built some sort of groundswell. But Fight Club went out as a big-studio film with movie stars.”

In the weeks before the film’s release, those stars were put on the defensive. “It’s a pummeling of information,” Pitt said of Fight Club in early October. “It’s Mr. Fincher’s Opus. It’s provocative, but thank God it’s provocative. People are hungry for films like this, films that make them think.” The movie’s early attackers disagreed. In a USA Today column, the conservative crusader William Bennett derided the movie’s “illicit, pummeling free-for-alls”—despite reportedly having not seen the film. Even more troubling was a column in The Hollywood Reporter, a major industry trade publication, that was published a week before Fight Club’s October 15 opening. Fincher’s movie “will become Washington’s poster child for what’s wrong with Hollywood,” wrote Anita M. Busch. “And Washington, for once, will be right.” She added that Fight Club “is exactly the kind of product that lawmakers should target for being socially irresponsible in a nation that has deteriorated to the point of Columbine.”

The world premiere of Fight Club was held in early September at Italy’s prestigious Venice Film Festival. It was the first indicator that not everyone found Mr. Fincher’s Opus especially funny. “It gets to one of Helena’s scandalous lines—‘I haven’t been fucked like that since grade school!’—and literally the guy running the festival got up and left,” recalled Pitt. “Edward and I were still the only ones laughing. You could hear two idiots up in the balcony cackling through the whole thing.” Adds Norton: “It got booed. It wasn’t playing well at all. Brad turns and looks at me says, ‘That’s the best movie I’m ever gonna be in.’ He was so happy.”

On October 13, just two days before Fight Club’s opening night, Mechanic called Fincher to prepare him for what was about to come. “I said there would be two judgments in the movie,” he says. “One would be on Friday—which I wasn’t so sure about. But there was also the judgment of history. And I thought this would be one of the great films of the decade. So I was fine to take the pummeling.”

Like Mike Judge and Brad Bird—two other filmmakers who’d known their movies were in trouble that year—Fincher decided to escape. That weekend, he and Fight Club producer Chaffin boarded a plane to Bali. We were thinking ‘Oh, it will be very peaceful. We’ll do some yoga, we’ll eat well, and get some sun on the beach,’ ” says Fincher. But not long after they landed, word began to arrive about Fight Club’s box-office performance. “The thing about the moviemaking business is that you do or die at six o’clock Eastern Standard Time,” says Chaffin. “That’s the old-school way: they call you up and say, ‘This is what it’s made tonight, and this is what we project for the weekend.’ And it’s either depressing or exciting. And when I got a call with the weekend figures, I was like, ‘Oh, my God.’ It was a stab in your heart.” Fight Club opened with just $11 million. A month after its release, the movie would slide out of the box-office top ten altogether. “Two years of your life,” says Fincher, “and you get one fax and it’s like, ‘Everybody go home. It’s going to be a fire sale.’ You do a lot of soul-searching at that moment: ‘Oh, fuck, what am I going to do now?’ How do you bounce back from that?”

Some of the blame for Fight Club’s failure was likely due to the film being sold as a brawl-filled punch-’em-up. “I had close friends say to me, a week after it was released, ‘I haven’t seen it yet—I’m not into boxing movies,’ ” says Uhls. “I was like, ‘Is that really what you think it’s about?’ ” There was also the fact that many who did go to theaters to see Fight Club had found it repellent—and were eager to warn off others. One afternoon shortly after its release, McCallany was sitting in the waiting room of his doctor’s office, where the television was tuned to The Rosie O’Donnell Show. “I was not somebody who ever watched Rosie O’Donnell’s talk show, but it happened to be on,” he says. “I heard her say [something like], ‘Whatever you do, don’t see Fight Club. It is demented. It is depraved.’ She went on this long tirade. I found myself looking at her, thinking ‘Why in the world would you attack us?’ It angered me.”

O’Donnell did more than attack Fight Club—she gave away the film’s third-act revelation, much to the frustration of the film’s cast, who were no doubt hoping for the same level of secrecy that had been afforded The Sixth Sense (“It’s just unforgivable,” Pitt said). Her outraged reaction was in line with the response of many film critics. The English writer Alexander Walker called it “an inadmissable assault on personal decency—and on society itself.” (Fincher had the quote reproduced on the packaging for the Fight Club DVD.) That was only slightly more harsh than the write-ups that appeared in the Wall Street Journal (which noted the film “reeks with condescension”), Entertainment Weekly (a “dumb and brutal shock show”), and the Los Angeles Times (a “witless mishmash of whiny, infantile philosophizing and bone-crunching violence”). The entire movie was picked apart. “One guy wrote scathing things about all of us,” says cinematographer Cronenweth, “but for me, he said, ‘Jeff Cronenweth has perpetrated the darkest-looking movie ever for a major studio.’ I think I was hurt for maybe a week. Then I started using ‘That’s right. I’m the perpetrator.’ ”

Norton, like many of the film’s creative team, was taken aback by the hostile response to Fight Club. “I think the establishment, the critical culture, felt a little bit indicted by it,” he says. “So they responded to it with a little bit more seriousness, and I think they missed the satirical edge of it.” During a conversation with his father Norton remembers his dad mentioned how much his own father had seen The Graduate as “a deeply offensive and subversive movie. I think there’s a fair analogy in the sense that, with Fight Club, you have to feel threatened by what it’s saying to think it’s an authentically nihilistic movie. And if you relate to what it’s saying, you think it’s a comedy.”

The response to Fight Club, Norton says, “really became a sort of a Rorschach test on where you sat. Not to put an ageist kind of spin on it, but I think people over a certain age had a very hard time. It really had a fairly generational split.” At one screening, Elliott Gould—the sixty-one-year-old star of such counterculture seventies comedies as M*A*S*H and The Long Goodbye—was reportedly overheard declaring, “That was awful.”

That’s how many greeted Fight Club within the film industry itself. There were grumblings around Hollywood that a major corporation like Fox should never have bankrolled such an irresponsible movie. One Hollywood Reporter story quoted several anonymous producers and agents describing Fight Club as “absolutely indefensible” and “deplorable on every level.” After its release, Fox CEO Rupert Murdoch yelled at Mechanic at a company meeting. (Mechanic can’t recall the exact wording, though he says it was along the lines of “You’d have to be a sick human being to make that movie.”) Fight Club arrived after years of animosity between the two men, and it was Mechanic who’d allowed Fincher to blow up 20th Century Fox’s corporate headquarters in Fight Club’s final explosions (it was the same building that had served as the terrorist-targeted Nakatomi Plaza in 1988’s Die Hard). Destroying Fox’s homebase, says Mechanic, “was my anti-Murdoch thing. My ‘Fuck you.’ ” Mechanic was fired from the studio in 2000, in part because of the aftermath of Fight Club.

Fincher also felt the glare of some of his peers—though it had less to do with Fight Club’s content and more with its commercial failings. For a while after Fight Club, he says, “People at Morton’s would pat you on the shoulders like you lost a loved one.” Not long after the movie’s release, he was called to a meeting at Creative Artists Agency, which represented him at the time. “The vibe was very much ‘It’s good you’ve experienced this and that you understand we can sway you from making these kinds of life-altering, possibly career-destroying decisions for yourself,’ ” he says. “I just got up and excused myself. And later on, I had a conversation and said, ‘How dare you? I’m really okay with this movie.’ ” Fincher wasn’t about to disappear. And neither was Fight Club.

In January 2000, Norton was attending a concert at Los Angeles’ Staples Center. “These young guys walked over,” he says, “and they were like, ‘Good to see you out, sir!’ ”—a reference to Fight Club’s Tyler Durden– worshipping followers. Recalls the actor: “I was like, ‘Whoa! People are having fun with this one.’ ”

They weren’t alone. Despite the movie’s box office and critical drubbing, Fight Club did manage to find a few early adherents. Critics at the New York Times and Rolling Stone praised the film, and debates over the film’s virtues—or lack thereof—could be overheard in movie-magazine offices for weeks and months. “I loved Fight Club so much—I saw it again and again,” notes Premiere editor Jill Bernstein. “It was detailed and delicious and ruthless. And we, as moviegoers, needed something raw like that.” Even Bill Clinton was a cautious fan, calling Fight Club “quite good,” if “a little too nihilist.”

In June 2000, Fox released Fight Club on DVD; it sold more than six million copies in its first decade of release. A movie that had once seemed so distastefully nihilist came to seem alarmingly prescient: It addressed the new rise of our-brand-could-be-your-life consumerism that would dominate the next century, and it provided an inadvertent blueprint for the sort of decentralized, shits-and-giggles anarchy that would later be adopted by online collectives like Anonymous. Not long after Fight Club’s release, days-long anti-capitalism riots erupted near a World Trade Organization conference in Seattle—another indicator of the economic frustration felt by Tyler and his peers. The movie seemed so eternally relevant, in so many ways, that the first rule of Fight Club became that everybody had to talk about Fight Club—even if they weren’t old enough to be a middle child of history. “When my daughter was about nine years old,” says Fincher, “I went to a school function, and she said, ‘Oh, I want you to meet my friend Max. Fight Club is his favorite movie.’ I took her aside and said, ‘You are no longer to hang out with Max. You’re not to be alone with Max.’”

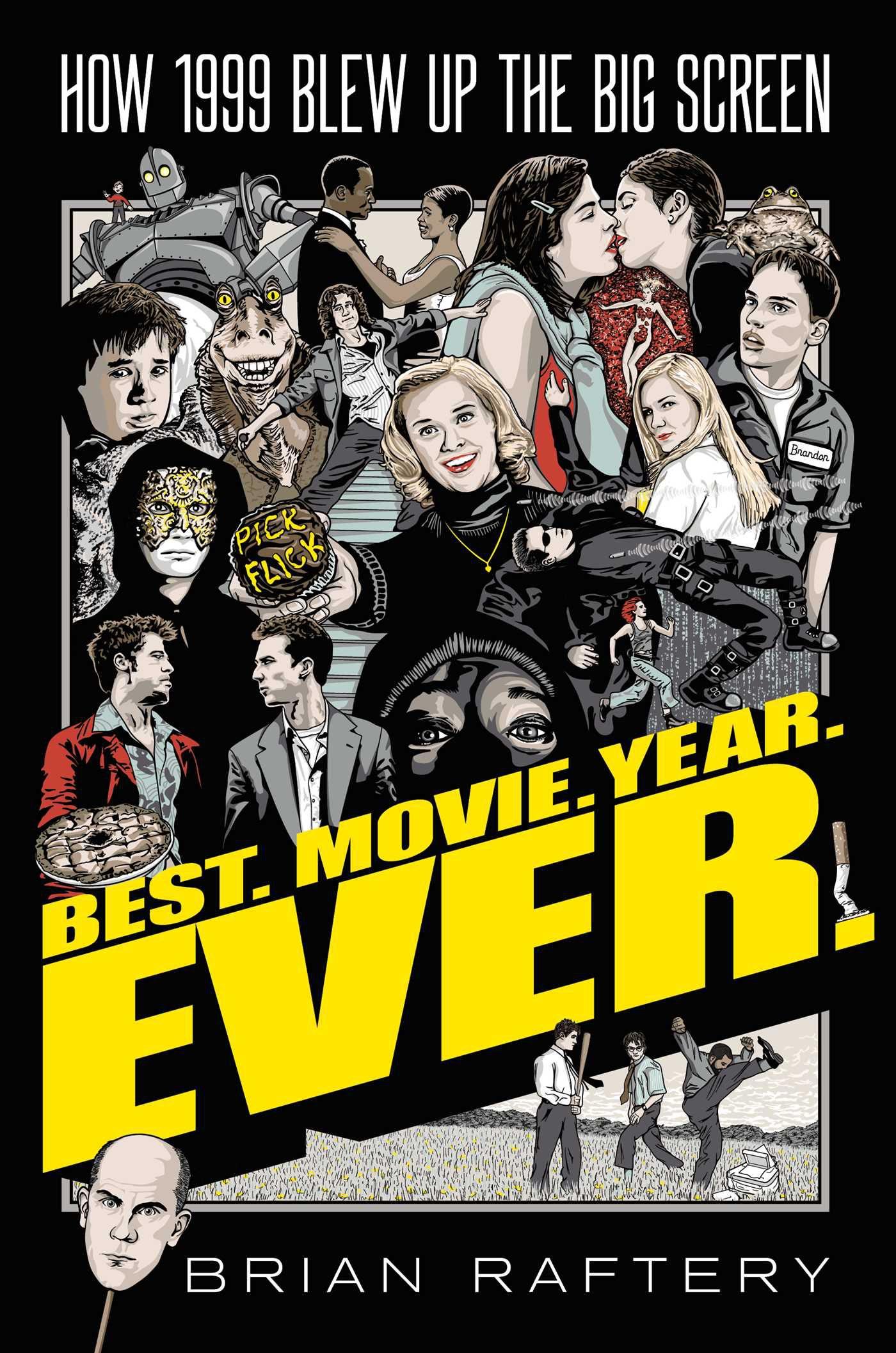

From BEST. MOVIE. YEAR. EVER.: How 1999 Blew Up the Big Screen by Brian Raftery. Copyright 2019 by Brian Raftery. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.