Last year, when Catherine Keener was promoting Incredibles 2, she was asked during a press junket whether she would ever reprise any of the characters she’s played in the past. “I can’t imagine, they’ve kind of all been put to bed,” she said. The interviewer then informed her that there is a theory that her character in Get Out is actually the same person as her character in Being John Malkovich. Keener blinked. “Because the whole idea of people being put into other people’s brains,” the interviewer said. Keener’s eyes went wide, and her face assumed an expression halfway between “people on the internet should go outside” and “I am alarmed by how much sense this actually makes.” Said Catherine Keener, “Wow.”

That was, roughly, my reaction when I first read about this theory last week, after rewatching Being John Malkovich. What a simpler existence I led just seven days ago, for now I am in the Sunken Place—a state of mind in which I believe that Get Out and Being John Malkovich occur in the same universe. (I’m calling it “The Mind Control Universe”; to keep you from confusing it with other cinematic universes I will refer to it as “The MCU.”)

That tinkling sound you hear of a spoon against a teacup? Don’t worry, that’s just me dragging you down into this abyss with me. Relax.

A surreal collaboration between screenwriter Charlie Kaufman and director Spike Jonze, Being John Malkovich is a tale as old as time: Three relatively miserable people stumble upon a portal into the mind of actor John Malkovich, which allows one to inhabit Malkovich’s body for 15 minutes before being dropped into a ditch near the Jersey Turnpike. An unwashed John Cusack plays Craig, a sad-sack part-time puppeteer and full-time office drone who lives with his animal-loving wife Lotte (Cameron Diaz and a wig) but falls in love with his seductive/disinterested coworker Maxine (an Oscar-nominated, aspirationally outfitted Keener). Maxine, in turn, falls in love with Lotte—but only when Lotte is inhabiting Malkovich’s body. Craig goes to increasingly disturbing lengths to keep the lovers apart, but he finally makes the mistake of climbing into the Malkovich portal just after it has closed, leaving his soul trapped in some sort of metaphysical purgatory. After becoming pregnant by the body of John Malkovich while Lotte was inhabiting it (I probably should have mentioned that this article is NSFW), Maxine gives birth to a daughter, Emily, whom she and Lotte happily intend to raise together. Except, as we learn in the last scene of the movie, Craig’s soul is actually trapped in the young daughter’s body. Talk about a classic setup for a sequel!

As the theory (which likely began on Reddit but has now become widespread enough to warrant its own lengthy section on the Being John Malkovich Wikipedia page) goes, Maxine and Lotte continued to crave the experience of inhabiting other people’s bodies, even after the Malkovich portal had closed. They eventually crossed paths with neurosurgeon Roman Armitage, the malevolent patriarch of Get Out, who transplanted the spirit of dressed-down Cameron Diaz into the body of Bradley Whitford (Malkovichy enough, I guess, given the options). Of course when you relocate your family to try and find illicit portals into other people’s consciousness, it’s always wise to assign everybody new identities, so “Rose Armitage” is actually grown-up Emily, and such is the nuance of Allison Williams’s performance that I didn’t even realize she was playing a disgruntled John Cusack trapped in a young woman’s body until at least the third viewing.

Obviously, the most glaring difference between these two films is that one is a thoughtful meditation on race in 21st-century America, while another is a movie about a bunch of white people who want to be John Malkovich. These stories may appear incompatible. If Maxine and Lotte really were as horrifically racist as the Armitage family, wouldn’t we have at least seen hints of that worldview in Being John Malkovich? I briefly believed this was a deal-breaker for this theory, until I fell even deeper into the Sunken Place and realized that the true, conscious architect of the scheme’s racism is Roman Armitage, who could have recruited Maxine and Lotte and in doing so awakened a latent hatred within them. If the internet can do this, so can Roman Armitage.

OK, fine, this all checks out, you are definitely thinking, but if all this were true, wouldn’t Rose Armitage, technically a vessel for the imprisoned spirit of Angsty John Cusack, be desperately in love … with her own mother? At which point I would remind you of the bottomless nuance in Allison Williams’s performance, which contains more notes than a fine rosé. Also … she kind of dresses like Maxine did in Being John Malkovich? Which may be her way of paying homage to her beloved mother’s peerless ’90s style.

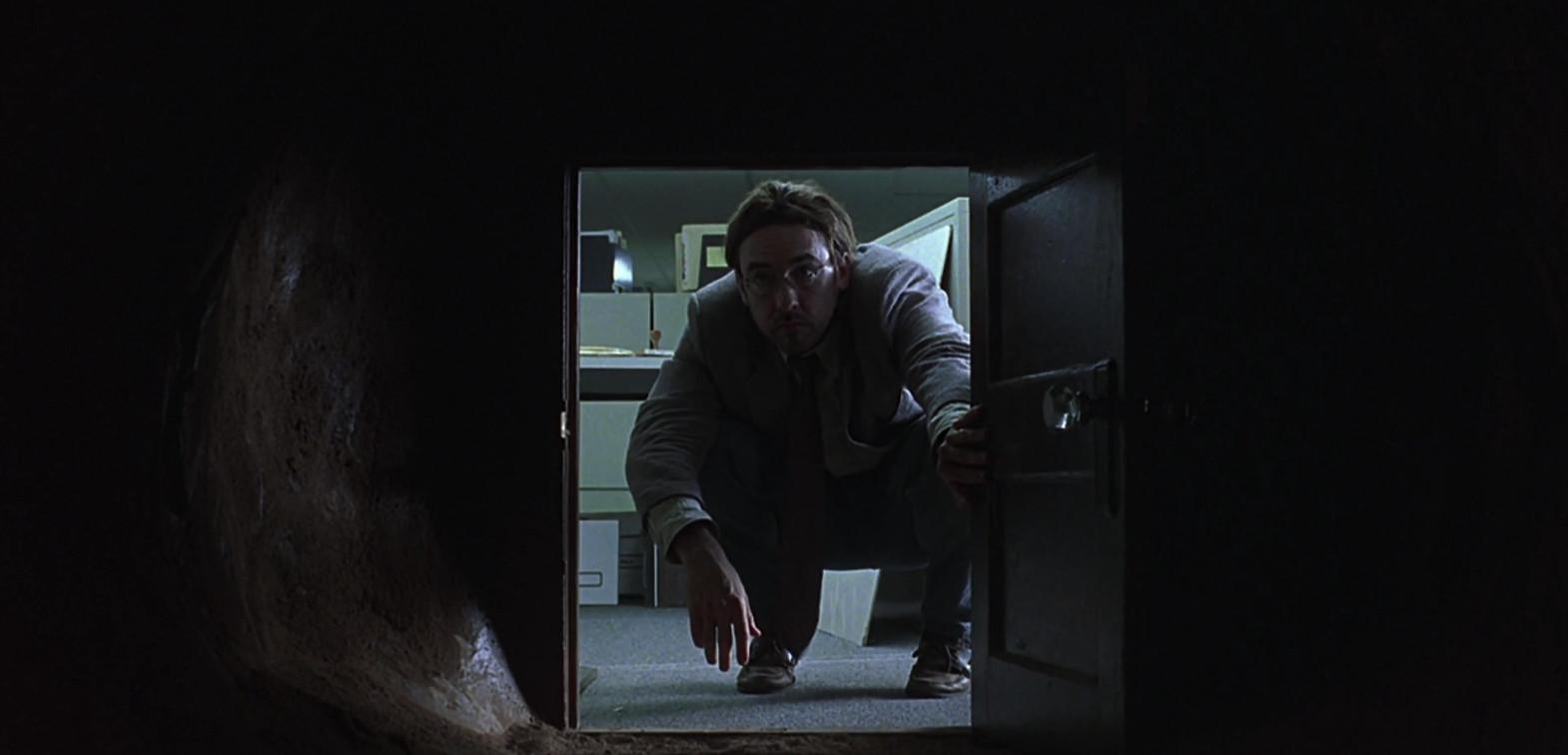

Still on the fence? What if I told you that the place where Chris finds the incriminating photos of Rose’s past paramours in Get Out is … BEHIND A VERY TINY DOOR?

In a December 2017 video for Vanity Fair, Jordan Peele was asked to comment on several Get Out fan theories. When he came to the Being John Malkovich hunch, he said, “I love this theory, I have heard this theory. It was definitely not lost on me that I was able to get Catherine Keener in her second, like, weird-perspective, living-in-someone-else’s-brain movie. We joked about that, and I’m a huge fan of the movie Being John Malkovich.” Peele claimed he even discussed it with Spike Jonze after Get Out was released, and the two shared a laugh. “So as far as I’m concerned,” Peele added, “it’s true.”

Maybe the deepest link between these movies is that they are both imaginative enough to keep fans talking and speculating about them long after their initial release. It’s a testament to Being John Malkovich that 20 years after it came out, people on an internet that barely existed back then are still trying to concoct theories that help wrap their heads around it. And although little is certain in this life—such as, say, whether or not the screaming demonic spirit of Craig Schwartz is inhabiting the body of Rose Armitage—I can say one thing for sure: We’ll still be musing about Get Out on its 20th anniversary, too.