The X-Men’s Never-Ending ‘Dark Phoenix Saga’ Saga

There’s a new movie about Jean Grey’s transformation into the Dark Phoenix. But didn’t we already see this movie? And didn’t this story appear in a Saturday morning cartoon? And in a historic run of comic books? The creators behind each of these stories talk about the undying power of the X-Men’s most iconic story, rising from the ashes once more.It was late 2004 and Tom Rothman, as he so often did, needed a writer. Then the chairman of Fox Filmed Entertainment, Rothman met with screenwriter Zak Penn about the third film in the X-Men franchise, and told him what else he needed. Stakes were high following the success of 2003’s X2: X-Men United, a critically acclaimed comic book movie—rare at the time—that had earned $214 million domestically, 36 percent more than its predecessor, 2000’s X-Men. But X3, as it was known during its development, was already in trouble.

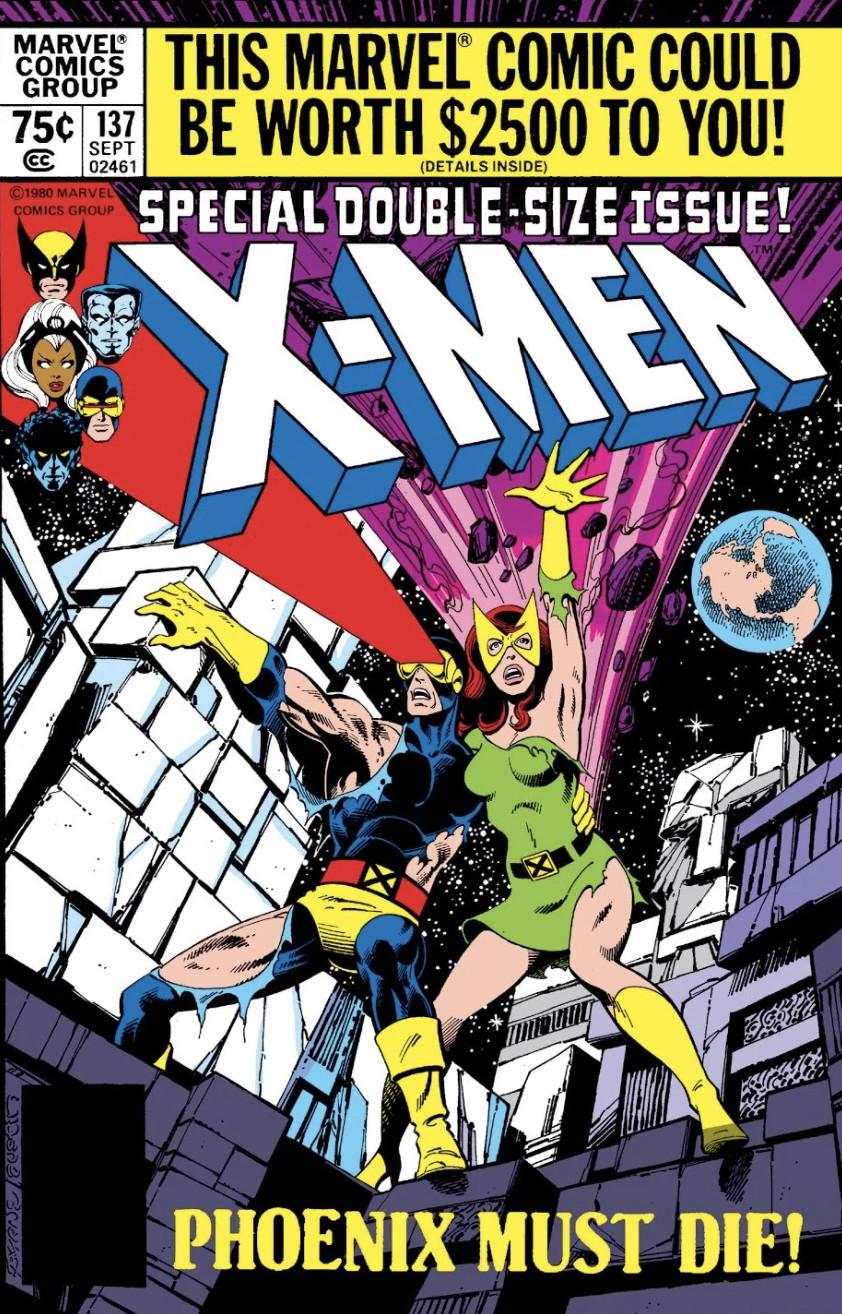

The plan was to adapt the Dark Phoenix Saga—a sweeping intergalactic epic that follows Jean Grey as she loses control of her awesome new powers, which she had previously assumed from the cosmic force known as the Phoenix. Unfolding over 10 issues of Uncanny X-Men (nos. 129-138) in 1980, the Dark Phoenix Saga is a heavy text featuring characters grappling with questions of life and death, purpose and power. It’s widely considered the definitive X-Men story. This wasn’t the first time someone had tried to adapt it, with maddening results. And it wouldn’t be the last. One thing that was certain: This plan wasn’t working. In part because Rothman was insistent upon shoehorning another unrelated story line, one about a mutant cure, into the film.

After Bryan Singer, the director of the series’ first two entries, exited the project to helm Superman Returns, Fox hired Simon Kinberg, who had written Mr. & Mrs. Smith and did a rewrite for the studio on Fantastic Four, to finish the story of Professor Charles Xavier and his students. Rothman considered Kinberg’s early drafts too dark, too weird, and, potentially, too expensive. The big set piece in the third act wasn’t working. In fact, the entire third act was uneven. And must the lead character commit suicide at the end—again? (Jean Grey sacrificed herself to save the rest of the X-Men at the conclusion of X2.) Known in the industry for his micromanagerial style, Rothman lived up to his reputation and delivered copious notes to Kinberg. And then he hired Penn, one of the credited writers on X2, to bring his vision to the film.

It’s common for studios to commission multiple screenplays for blockbusters and then tab a third writer to stitch together a shooting script. Penn wanted to avoid that scenario, so he pitched Rothman something different: He’d collaborate with Kinberg on a script. Soon, the two writers were swapping ideas. “We hit it off immediately,” Penn remembers. “Simon was a hard worker and so was I. I had an office and we stayed in that office and we just fucking jammed.”

After a week or so, Penn and Kinberg had 80 pages, roughly two-thirds of a script. And they’d solved their biggest challenge: how to depict the Phoenix force. “It was just a matter of taking out the ‘bird of fire that had lived since the beginning of the universe’ idea,” Penn says. “As a kid, I thought it was super cool. As a screenwriter trying to establish tone, it felt impossible to explain to anyone except hardcore fans.”

But given the presence of the cure story line—which was drawn from the Gifted series in Astonishing X-Men nos. 1-6—the long-awaited Dark Phoenix adaptation wasn’t really a Dark Phoenix adaptation. “That was more of a mandate from the studio. ‘OK, interweave these two plots,’” Penn says. “That’s when things got trickier.”

Released on Memorial Day weekend 2006, X-Men: The Last Stand relegated the Dark Phoenix story line to its secondary story. In doing so, hardcore fans—the ones who take the idea of a bird-of-fire-that-had-lived-since-the-beginning-of-the-universe very, very seriously—turned on the film. The Last Stand is now shorthand for a franchise-killing debacle, even though it made tons of dough and [whispers] wasn’t that bad.

More than anything, it fueled the notion that adapting the original text for the big screen was a Sisyphean task. After all, the Dark Phoenix Saga includes a main character facing an intergalactic trial after committing genocide, and a climactic battle between mutants and aliens on the moon. Too dark. Too weird. Too expensive. And yet, it’s not Cloud Atlas or Paradise Lost. The right filmmaker making the right choices could craft the perfect Dark Phoenix Saga movie. Fox is betting Simon Kinberg is that filmmaker.

Written and directed by Kinberg, X-Men: Dark Phoenix is Fox’s—and Kinberg’s—second attempt at the iconic story. And with the film arriving in theaters this week, it’s the right time to examine the history of the Dark Phoenix Saga. How was it created? What makes it so powerful? Why do creators keep returning to it? And what can Kinberg and Fox learn from previous adaptations?

Chris Claremont arrived at a brainstorming lunch with his editor, Jim Salicrup, and Marvel’s then-editor-in-chief, Jim Shooter, prepared to share his long-term plans for Jean Grey. It was 1979. The London-born, Long Island–raised writer had been kicking around a potential story arc for the mutant who had transformed from Marvel Girl into the all-powerful Phoenix in X-Men no. 101. What if … Jean became corrupted by her new powers? What if … she became an adversary for the X-Men?

Shooter liked the concept. While there was a history of Marvel villains becoming heroes (Black Widow and Hawkeye), he couldn’t name a character who had switched from good to evil. He envisioned Phoenix as a perpetual nemesis to the team, the X-Men’s Doctor Doom. Claremont, the writer and, along with penciler John Byrne, the co-plotter of Uncanny X-Men, considered a more nuanced story arc. He preferred great themes: power corrupting and absolute power corrupting absolutely. He pitched the weakness and wills of humanity—human emotions, human passions, and human limitations. “John and I wanted to take [Phoenix] down a path no one had gone through before,” he says.

Ambitious story lines were a hallmark of the Claremont-Byrne X-Men, a run that resurrected the once moribund title. While it’s now one of Marvel’s best known comics, X-Men, long after its 1963 debut, lagged in relevance and sales behind those featuring Spider-Man and the Fantastic Four. The book was cancelled in 1970 and went into reprints until 1975’s Giant Size X-Men.

The revamped lineup featuring Jean Grey and Cyclops as the only returning members of Xavier’s original team arrived the following year as a bimonthly with Claremont writing and Dave Cockrum penciling; Len Wein, who cocreated the X-Men Nightcrawler, Storm, and Colossus, served as co-plotter early on. John Byrne succeeded Cockrum in 1977, starting with X-Men no. 108. The book became a monthly during his tenure.

The book’s masthead—Claremont, Byrne, Roger Stern, and later Jim Salicrup as editor, Terry Austin as inker, Tom Orzechowski as the letterer, and Glynis Oliver-Wein as the colorist—was filled with professionals. Deadlines were met. People were reliable. Nobody screwed around. This was work. This was a job.

Though an ascendant title, Uncanny X-Men (the name was changed in 1978) benefitted from modest expectations. “They had a freedom to do things, to try things with characters that I don’t think they would’ve been given had they been working on the traditional best sellers,” Salicrup says. “That opened the doors for a lot of creative freedom and I think those guys rose to the occasion. I got to witness it. Even when I was an assistant editor, I was like a glorified fan.”

The Claremont-Byrne team was a true collaboration fueled by creative tension. During good times, they’d devise elaborate plots over the phone and Byrne would draw from memory. Claremont would later add dialogue to Byrne’s artwork. (During bad times, Byrne would seethe over how Claremont wrote the characters.) As a writer, he maintained a consistent voice. The characters were treated with a respect and affection that Claremont maintains. He still refers to Professor Charles Xavier as “Charlie.”

The original X-Men were students. Kids. Ordinary people with extraordinary abilities that set them apart from society, and in some cases, set them apart from their own families. It wasn’t the Justice League. It wasn’t the Avengers. They had no rule book. A lot of it didn’t make sense to them. But here at this school, and with this teacher, there was a possibility that a normal life—one that didn’t revolve around fear and ostracism—could be had. The original X-Men needed each other.

To this day I meet people at conventions and they tell me that the X-Men saved their life.Jim Salicrup, X-Men editor

Claremont’s X-Men were in their 20s. But the team was still a surrogate family. “With the way the world can be at times, a lot of people need to retreat into this world where they feel it’s OK to be different, and even if everyone hates you, you’re still good, you still have value, you are worth something. It was a great message,” Salicrup tells me. “To this day I meet people at conventions and they tell me that the X-Men saved their life.”

The Dark Phoenix Saga was born in X-Men nos. 101-108, in which Jean Grey, then known as Marvel Girl, assumes the power of the Phoenix force. But what is the Phoenix? When reached last week at his home in North Fork, Long Island, Claremont elliptically lays it out this way: “The way I always described it is that the Phoenix is one half-step down from the creator. What Phoenix’s responsibility is at the end of time when all the stars in creation have gone out, the Phoenix is the last light to go out, but it’s also the first light reborn an instant later. It’s a never-ending circle.”

An hour into the conversation, he says, “For me, there is an aspect of Jean that was always the Phoenix. There is an aspect of the Phoenix that is always Jean.”

The Marvel editorial team was split on whether the Phoenix possessed Jean —like the demon did to the little girl in The Exorcist—or was already a part of her. It required an upgraded costume and a name change. But the power was a burden for Jean and she lost control of it during the Dark Phoenix Saga.

The plot must be explained to understand what filmmakers attempting to adapt the story are dealing with here. A quick summary: After falling under the control of Mastermind and the Hellfire Club (villains, if you couldn’t tell by the names), Phoenix betrays the X-Men. She soon frees herself from Mastermind’s grip, but it comes with a price. It unleashes her full potential. Now christened the Dark Phoenix, she departs Earth and in her travels devours a star, resulting in the deaths of 4 billion of the D’Bari people. She then attacks a Shi’ar vessel.

Once back on Earth, the former Jean Grey embraces her new abilities—the power excites her—and she engages Professor X in a psychic duel. Xavier then places psychic restraints on her, reducing Dark Phoenix to her previous powers. All seems well with the old Jean back, in love with Cyclops and showing little interest in planetary genocide. But an intergalactic council declares that “Phoenix Must Die,” as the cover line from Uncanny X-Men no. 137 screamed. The X-Men and the Shi’ar Imperial Guard then fight on the moon with Jean’s fate in the balance. When the Dark Phoenix reemerges, Jean realizes she can’t control her power and kills herself.

“It was our Game of Thrones,” Zak Penn says, “a comic book that was so much richer and darker than the other stuff.”

The Dark Phoenix Saga also introduced Kitty Pryde and villains such as Emma Frost, Sebastian Shaw, and the Hellfire Club into the X-Men universe. Wolverine’s breakout moment also arrived during the series, specifically on the pages of X-Men no. 133 as he emerges from the sewers and goes berserker on some Hellfire Club goons. But ultimately, it was the operatic, sophisticated storytelling combined with Byrne’s peerless artwork that made it an instant classic.

Jean Grey’s sacrifice turned the Dark Phoenix Saga into a heroic tragedy and defined the team moving forward. But it almost didn’t happen that way. The original X-Men no. 137 ended with Lilandra, the Shi’ar Empress, performing a “psychic lobotomy” on Jean to strip her of all her mutant powers. Marvel editor-in-chief Jim Shooter thought “it wimped out” and demanded a different ending. He was steadfast in his belief that Jean should face consequences for her actions—namely, killing 4 billion innocent D’Bari. There was one problem: The comic was deemed complete and ready to be shipped to the printer.

How did this happen? An understaffed team juggling multiple responsibilities had a simple miscommunication. “It turned into Rashomon,” Salicrup says, referring to the 1950 Akira Kurosawa film that gave name to the Rashomon effect, in which several people remember a single event differently. “I had an idea of what the story was supposed to be. Jim had an idea. Chris and John had their idea. Unfortunately, it wasn’t the same idea.”

What her death gave to the characters and to the concept was the reality that actions have consequences, which is something that is woefully nonexistent in traditional corporate-owned superhero stories.Chris Claremont, X-Men writer

Claremont was furious when Shooter ordered the alternate ending for X-Men 137. “I thought it was cleared,” he says now. He remembers then conferring with Shooter and X-Men editor Louise Simonson—it was Simonson’s first issue on the job—and deciding that, yes, Phoenix Must Die! There was no alternative.

“At one level, I was really pissed. At another level, it was the right ending,” Claremont says. “What her death gave to the characters and to the concept was the reality that actions have consequences, which is something that is woefully nonexistent in traditional corporate-owned superhero stories.”

It was also a wise business decision. Jean Grey’s demise was the most memorable superhero death during the Bronze Age of Comic Books. X-Men’s popularity skyrocketed and by the mid-1980s, it became Marvel’s best-selling title. “We were able to say to the audience, ‘You can not take this book, these characters, these events for granted,’” says Claremont, who wrote X-Men until 1991. “If we can kill Jean, we can do anything, and if we can do anything you have to pay attention.”

X-Men: The Animated Series, the beloved Saturday morning cartoon that aired on Fox from 1992 to 1997, was the first to take a crack at adapting the Dark Phoenix Saga. Like most comic book properties, it had a perilous journey to the screen. Even after a previous attempt at bringing the X-Men to Saturday mornings failed—1989’s Pryde of the X-Men died in the pilot stage—Fox Kids CEO Margaret Loesch believed that superheroes could thrive on the network. According to a recent Hollywood Reporter oral history of the series, Loesch “staked her career on its success.”

One of her first moves was hiring animator Larry Houston, who had worked on Pryde of the X-Men, as a producer and director. A comic book fanatic since the 1960s and a longtime X-Men reader, Houston wasn’t interested in making Scooby-Doo. Talking cars and funny animals would not appear on his show. He refused to write down to the kids watching. Expectations, among the network executives, were not high.

The show premiered on Halloween 1992 with the first episode of the two-part “Night of the Sentinels.” A third episode aired on Thanksgiving weekend, but the series then vanished due to production delays. The show was an immediate hit upon its return in January, with ratings slightly below those of Fox’s blockbuster Batman: The Animated Series, even though much of the writing staff weren’t comic book fans. “As a kid, I was more into Mad magazine,” says writing team leader Eric Lewald, who later chronicled his experiences in the book Previously on X-Men. “By the time we started laying out the first season of stories, I don’t think I had read more than half a dozen comic books.”

Houston was the comic expert and supplied his staff with a crash course on the books—the relationships, history, and character traits, etc. More than anything, he stressed reverence to the comics. “I am one of those directors who respects the source material,” he says. “I believe that when you are adapting from a book that you should only change stuff when you have to, not because you can.”

He would soon have to adapt. When the show decided to tackle the Dark Phoenix Saga in Season 3, Houston was forced to make several changes. Jean Grey’s transformation into the Phoenix occurred earlier in the season. By this point, the show was such a hit that Fox offered little pushback—Marvel had zero influence over the series—but there were network standards to uphold. Dark Phoenix couldn’t kill 4 billion D’Bari and she couldn’t die at the end. In fact, the words, “death,” “kill,” and “hell” were banned from the series—the Hellfire Club was even rechristened the Inner Circle.

Houston and his team settled one debate early: The Phoenix would be treated as a possession, that way, he says, “we could take the evil out of her and she can return to normal.” There were other challenges with the four-part series. Houston labored over animating cosmic characters such as the Shi’ar and the Imperial Guard, as it was paramount that the aliens didn’t look silly.

Lewald’s biggest struggle, meanwhile, was depicting the characters’ thoughts, without the convenience of thought bubbles. “Comic books have all this internal dialogue, so you are constantly getting a sense of what everybody is thinking about their place in the world and their emotions. … In Dark Phoenix, there was a lot of internal monologues,” he says. “We had to get that across in looks and gestures and action.”

The biggest departure for the animated series was, of course, the conclusion. Once again, Lilandra orders that the Phoenix must be destroyed (even though the planet she had destroyed was uninhabited) and there is a battle on the moon between the X-Men and the Imperial Guard after which Jean sacrifices her life. That’s when things take a turn. The Phoenix force manifests as a giant bird of fire, proclaiming that Jean’s “radiance could be rekindled with the flame of another.” Following a brief argument between Cyclops and Wolverine, the Phoenix tells the team that they can each contribute to Jean’s resurrection. Scott and Jean smooch. The Phoenix screeches before departing and the X-Men return to their mansion.

“We needed a concrete answer with five minutes remaining for how we got the Phoenix out from Jean’s body. That seemed to be the most dramatically satisfying,” Lewald says. “It would’ve been nice if she died, but we couldn’t do that.”

When X-Men was released in theaters on July 14, 2000, comic book movies were still dealing with the enduring stench of Batman & Robin. That meant Bryan Singer’s movie was a $75 million risk for Fox following its long road out of development hell.

An X-Men movie had been kicked around Hollywood since 1984, with Kathryn Bigelow, Robert Rodriguez, and Paul W.S. Anderson discussed as potential directors at one point or another. A cavalcade of writers, including Andrew Kevin Walker and Joss Whedon, wrote drafts; the novelist Michael Chabon also did a treatment. Casting, meanwhile, was all over the place. For Wolverine alone, Bob Hoskins, Mel Gibson, Russell Crowe, and Viggo Mortensen were among those considered. Glenn Danzig once auditioned for the role. Hugh Jackman was eventually cast weeks into filming, replacing Dougray Scott after he suffered injuries on the set of Mission: Impossible II.

Despite its tumultuous past, X-Men was a hit, earning $157 million domestically and $296 million worldwide. Singer’s film worked for a simple reason: It was grounded in a kind of mutant reality. This was largely uncharted territory for comic book movies.

A naturalistic Dark Phoenix Saga, on the other hand, is hard to imagine. Yet that was where the franchise appeared to be heading after X2: X-Men United, which closed with a Phoenix silhouette appearing in the waters of Alkali Lake. For X-Men: The Last Stand, Simon Kinberg and Zak Penn, the writers, approached the Phoenix psychologically as opposed to cosmically, keeping the X-Men Earth-bound and grounded in the universe Singer had created. “You can’t do the cosmic story of Jean and Phoenix and Gifted all in one movie,” Penn says, “because I don’t know how you do the cosmic story of Jean. That took a ton of issues to do. It’s a really complex story.”

Also handcuffing the writers was the studio’s meddling with various aspects of the story and its caution during the productions. “I think the studio was not as adventurous about doing something that was dark. Literally dark. They wanted materials that were daylight. They were worried about selling this for TV and they didn’t want us to shoot at night. Why do we have to shoot at night? Can’t we shoot during the day?” says Ralph Winter, a producer on the initial X-Men trilogy. “I always say that we edged the door open with X-Men and Spider-Man kicked the door open. They spent a tremendous amount of money and made tremendous box office and Fox wasn’t quite ready to step up to that level. So they were nervous.”

Before expanded universes and the serialized movie storytelling pioneered by the MCU, X-Men: The Last Stand’s $210 million budget earned it the title of the most expensive movie ever made when it opened. (It didn’t hold the record for long—the $225 million Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest was released six weeks later.) Rothman had shareholders to answer to and quarterly goals to meet. He made the safe choice and X-Men: The Last Stand is a safe film.

It’s hard to know how a radical portrait of the Dark Phoenix Saga would have been received. This was before Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight cast an ominous, noirish shadow over superhero stories. Audiences were not prepared for a superhero movie to go there, and the early scripts for X-Men: The Last Stand, apparently, went there. “I remember it was dark and there was a lot of destruction,” says David Gorder, an associate producer on the film. There was also concern about betting $210 million on a female lead. The Last Stand was released in 2006, on the heels of flops like 2004’s Catwoman (which earned $40 million domestic against a $100 million budget) and Fox’s own Elektra, released in 2005, which collected just $24 million at the domestic box office. Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel were more than a decade away. A Jean Grey–fronted film was perceived as too risky for the studio.

Before departing the project in the summer of 2004, Bryan Singer and his writing team produced a treatment for the film that focused on the Dark Phoenix Saga and included the Hellfire Club; Sigourney Weaver was considered for the role of Emma Frost. But that treatment was jettisoned long before Layer Cake director Matthew Vaughn was hired in March 2005 following an arduous search.

From the start, Vaughn, a young filmmaker, was concerned with the production schedule, even after the release date was pushed back from May 5 to Memorial Day weekend. Filming was set to begin in summer of 2005. Pre-production then turned into a slog, with casting issues stalling momentum. The studio also still had concerns about the third act. With that, Vaughn dropped out in May 2005. Around that time, Ain’t It Cool News, then the premiere online destination for movie gossip, posted a scathing, spoiler-heavy review of Penn and Kinberg’s script. Fox executives read the site, even the comment section, and according to David Gorder they were concerned about the negative buzz swamping the film.

The Dark Phoenix story is the ultimate X-Men story. To get a chance to tell it onscreen and sideline it to the B-plot of the film ... It’s like if you are a kid and you are really religious and you finally get a chance to tell the story of the Bible and you sideline Genesis. It’s kind of a bummer.Simon Kinberg, writer, director, and producer of X-Men: Dark Phoenix

Fanboy skepticism would soon turn into fury: Fox replaced Vaughn with Brett Ratner. Years before #MeToo controversy engulfed his career, Ratner’s reputation as a filmmaker was, generously, that he was a hired hand.

“Now he comes with even more baggage, but back then he had a lot of baggage. The assumption of fans was, ‘Well, he sucks, so this movie will suck,’” Penn says. “That’s the way fans are. I don’t think they realize that Brett, when you look at his movies, he’s generally a pretty good chameleon at making his style fit the subject matter. He really kind of tried to make it feel consistent with what Bryan was doing. It’s not like they brought in the Farrelly brothers to direct it. It was someone who had done other franchise movies and had a sense of what the tone should be.”

Ratner sought gifted craftspeople for the film—Michael Mann’s go-to cinematographer, Dante Spinotti, was chosen for DP—but he was, in this case, just a hired hand appointed to fix the climactic set piece and finish the film to make its summer holiday release date. Which he did.

Though the fanboys of the Ain’t It Cool talkback section were disappointed, X-Men: The Last Stand was considered a success by Fox. The film banked $102 million in its opening weekend—a Memorial Day weekend record—on its way to $234 million domestic, still the highest total for any X-Men film; only 2014’s X-Men: Days of Future Past surpassed its $459 million global haul.

While he is still bothered by how the film shelved Jean Grey in the final act, Penn stands behind it. “I’ve had a million arguments with people,” he says, sounding exasperated. Simon Kinberg, meanwhile, shared the fans’ deep disappointment.

“The Dark Phoenix story is the ultimate X-Men story. To get a chance to tell it onscreen and sideline it to the B-plot of the film is not the Dark Phoenix story. That was really my heartbreak of that movie was that we didn’t get to tell this story that for me was my favorite story growing up,” he says. “It’s like if you are a kid and you are really religious and you finally get a chance to tell the story of the Bible and you sideline Genesis. It’s kind of a bummer.”

Simon Kinberg first considered revisiting the Dark Phoenix Saga in 2013 while on the set of X-Men: Days of Future Past, the sequel to Matthew Vaughn’s series reboot X-Men: First Class. The time-travel epic erased, for the most part, the events of the initial trilogy from the X-Men cinematic canon. “I was very aware that I was resetting the timeline,” Kinberg says. “I was aware that it was giving us an opportunity to tell the Dark Phoenix story again the way I felt it deserved to be told as the primary plot, the central plot, the only plot of the movie.”

In the years since X-Men: The Last Stand, Kinberg became the spine of Fox’s Marvel unit, producing the studio’s X-Men films, including Deadpool and Logan, and notching writing credits on Days of Future Past, X-Men: Apocalypse, and the disastrous 2015 Fantastic Four reboot; Kinberg also produced the Academy Award–nominated hit The Martian. Fox announced in June 2017 that Kinberg would write, direct, and produce X-Men: Dark Phoenix.

When we spoke last month, Kinberg referred to the film as “the first real attempt to tell the Dark Phoenix story.” He compares The Last Stand’s handling of Dark Phoenix to Deadpool’s bizarre cameo in X-Men Origins: Wolverine, where the chatty character known as “The Merc With a Mouth” appeared with—get this—his mouth sewn shut.

He says that his greatest challenge on the film was balancing the intimate and the epic, introducing intergalactic elements to the film while focusing on Jean Grey’s moral dilemma and that of her loved ones. To understand what he is going for here, consider how Kinberg prepared Sophie Turner for the role of Jean Grey: He sent Turner books, articles, and YouTube clips about people experiencing mental health issues such as schizophrenia and dissociative personality disorder.

“I wanted it to be raw and gritty and grounded and real, more of a cousin to Logan than to the X-Men films,” he says. “The look of it, the feel, the tone of it is really wildly different than any of the X-Men movies, but certainly The Last Stand.”

X-Men: Dark Phoenix shares certain elements with The Last Stand, and not just due to their turbulent productions; Dark Phoenix underwent extensive reshoots and pushed its release date from November 2018 to February 2019 to June 7. Spoilers ahead.

As in the 2006 film, Professor X’s hubris triggers disaster and Dark Phoenix kills a major character early on. Magneto and various disposable mutants are shoehorned into the film. There is no mention of the Hellfire Club. Most surprising of all, Jean is off screen for a large portion of the third act. Kinberg, though, has a respect for and knowledge of the source material. Dazzler and the D’Bari appear. Jean’s struggle with her newfound powers are a significant part of the film. Her fate is decided in a climactic battle between aliens and mutants that takes place not on the moon, but on a speeding freight train.

Perhaps Dark Phoenix’s greatest test is convincing the audience that it’s something fresh and not a remake of a film released 13 years ago. “I went to see John Wick 3 out here and I saw the trailer for the new X-Men,” says Ralph Winter, calling from Thailand where he is scouting for the Michael Mann–directed miniseries Hue 1968. “You know, it feels like it’s the same story again, that she dies and is more powerful—and I don’t know.”

Chris Claremont has a theory as to what makes the Dark Phoenix Saga difficult to adapt. “The cheap answer is that no one lets me write it,” he says. “I’m actually not being facetious.” (Claremont had not seen X-Men: Dark Phoenix at the time of our interview. “I hope it will be brilliant,” he says.)

It’s been his goal for decades. He remembers the X-Men premiere in July 2000 on Ellis Island when Famke Janssen, who portrayed Jean Grey in the original trilogy, asked him when he was going to write her a great Phoenix story. “I said, ‘Yeah, give me the word and I’ll give you one that will knock your socks off,’” he says. “That never came to pass, but that was my ambition, to go out west and write the kick ass X-Men Phoenix story.”

Claremont then shares his kick-ass Phoenix story, which would slow-pedal the Dark Phoenix Saga across two films. Surprisingly, Claremont’s idea diverges from the comics, with Cyclops and Jean’s daughter Rachel (he would also cast Sophie Turner) playing a major role. But it wouldn’t be a complete departure. Phoenix still devours a star, killing 4 billion D’Bari. The Shi’ar attempt to extract punishment. “I would love to have 200 million bucks to do my version,” he sighs. “I suppose the frustration of being the author of the source material is this sneaky feeling that I know these guys better than anybody and I know the story better than anybody.”

While Claremont isn’t getting $200 million to make his film, not anytime soon, there is a possibility of another Dark Phoenix movie on the horizon. With Disney’s recent $71.3 billion acquisition of 21st Century Fox’s film properties, Marvel owns the X-Men. A faithful adaptation of the Dark Phoenix Saga requires time and no one does long-term franchise building and management like Marvel Studios.

Picture it: Marvel Phase Whatever. After four successful X-Men movies and the inevitable Wolverine stand-alone, Marvel unleashes the first film of a two-part event: the Dark Phoenix Saga. In theaters May 2035. Maybe sooner. Or, maybe never.

Thomas Golianopoulos is a writer living in New York City. He has contributed to The New York Times, BuzzFeed, Grantland, and Complex.