Eleven Miles, but a World Away: The Warriors Make Their Last Stand in Oakland

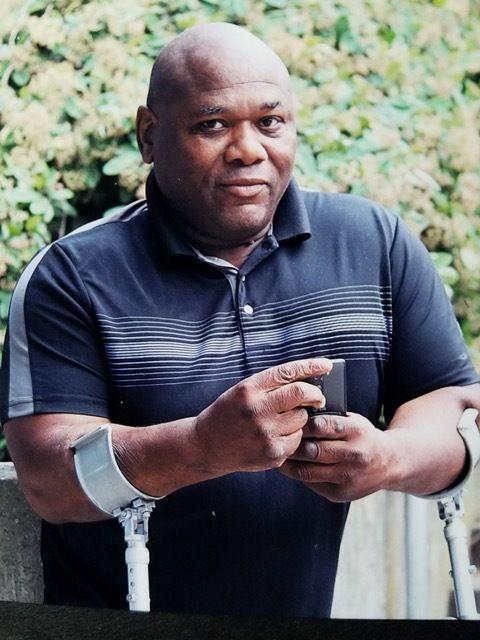

As Golden State looks to secure its fourth title in five seasons, the team is also preparing for its move to San Francisco. And while the distance between Oracle Arena and the new Chase Center may seem small, for many longtime Warriors fans and Bay Area residents, the significance of the shift is much greater.At the corner of 16th and 3rd Streets in San Francisco, a man named Allen Jones leans on a pair of crutches and gazes upward. The sidewalk is vibrating from nearby construction; office buildings have risen to fill every hole in the block; the Muni train station platform is being widened to accommodate more passengers; and at the center of it all is the glistening white whale of an arena whose presence feels, to Jones, like an assault on his hometown’s erratic sense of morality.

One more summer of jackhammers and cranes and the final touches will be complete: More than seven years after the idea of moving the Golden State Warriors from Oakland to San Francisco was first broached by its ownership group, the privately financed, billion-dollar waterfront entertainment complex known as the Chase Center will open its doors in September. The hottest franchise in the hippest professional sports league in America—the team constructed on Silicon Valley precepts that disrupted the way basketball is played behind the elite core of Steph Curry, Klay Thompson, Draymond Green, and, for now, Kevin Durant—will pack up its things, cross the four-mile-long Bay Bridge, and settle into its new home, where suites run for up to $2 million per season and Metallica floor seats are circulating for $6,600. This is happening, and there is no conceivable way of stopping it.

But that’s why I’m standing on this corner with Allen Jones: Because he might be one of the last people in San Francisco who refuses to accept this stratified future as an inevitability. Even as he looks upon the facade of an arena that’s nearly finished, Jones believes he can still stop the Warriors, who will host Game 3 of the NBA Finals in Oakland on Wednesday, from ever playing a game in San Francisco. And if this sounds ludicrous, that’s because it probably is. But at least it’s of a kind with the mind-set that long rendered San Francisco unique. Jones, a retired draftsman who was born and raised in this city, is a political gadfly and activist; the local alt-weekly East Bay Express described him as an example of “a dying breed of outspoken, perhaps hyperbolic, San Francisco rebels; those who never got the memo that they’re required to shrug off and accept the sight of average Joes being crushed by corporate behemoths.”

Jones is a broad-chested man with a shaved head who veers from one point to the next in what often seem like non-sequiturs. As we’re talking, he reaches into a small satchel and hands me a copy of his self-published autobiography, which describes his upbringing in San Francisco’s Mission District with eight brothers and sisters in the 1960s and 1970s. It details the origins of the spinal condition that has since childhood rendered him unable to walk unassisted, and discusses his awakening as a gay man; it also articulates his views on how San Francisco, for all its progressive spirit, has historically mistreated and marginalized its African American population.

For all the noise Jones makes about San Francisco’s inequities, for all the complaints he raises about the perceived arrogance and ignorance of local politicians, he also harbors a deep affection for the Bay Area’s underlying resilience, and its sports teams have often embodied that. His first truly fond memory of the Warriors, he tells me, was watching guard Al Attles—who played for the franchise from 1960-61 to 1970-71, with nine of those seasons taking place after the franchise moved to San Francisco—defend a teammate during a fight, because it was the first time he’d seen a black man stand up for a white man. What the Chase Center represents, to Jones, is an affront to the character of the region. Jones says this team is being “stolen” from a historically black neighborhood in east Oakland and being deposited into Mission Bay, a largely white neighborhood with a median household income of $134,000. And that is a betrayal that should not be ignored, particularly in a city that’s rapidly becoming a bleak caricature of itself in the gilded age of tech gentrification.

Jones views this final stand he’s taking against the Chase Center as the last gasp of his fight: In the summer of 2018, with the financial help of insurance salesman and former Golden State suite holder Jim Erickson, Jones gathered signatures for one of the most peculiar ballot initiatives in recent memory. Proposition I asked San Francisco residents whether they agreed the city should “not invite, entice, encourage, cajole, or condone the relocation” of the Warriors—or, as the measure described, “any professional sports team that has previously established itself in another municipality and has demonstrated clear and convincing support from community and fans for at least 20 years and is profitable.”

The proposition wouldn’t have changed anything by itself—the Chase Center is a privately funded project, and after the initial waterfront site the Warriors targeted gave way to the current one in Mission Bay, a series of legal challenges by an opposition group were struck down in 2017. But for Jones, this fight feels more existential. It’s almost as if he’s hoping to rouse people from their helpless sense of inevitability about the future of the Bay Area. Pass this one symbolic measure, Jones figured, and maybe it would lead to more.

Proposition I gathered 97,863 votes in favor, but it lost decisively, with only 42.78 percent of the overall vote; the San Francisco Chronicle recommended a “No” vote, because “it won’t have any effect.” But Jones is not finished; he tells me he’s not the kind of man who backs down easily. Since his family home in the Mission got foreclosed upon about a decade ago, Jones has mostly lived out of his truck. After his laptop got stolen out of that truck, he typed the text for the ballot measure on his cellphone; after his truck broke down a few months back, he moved in with his sister, where he wrote a letter of apology to the city of Oakland on behalf of the 97,863 people who voted in favor of the proposition. Now, he’s hoping to plead his case directly to NBA commissioner Adam Silver, to explain how he believes the Warriors are flaunting the values of a league that prides itself on advocating for social justice.

Jones tells me he’s thought of a way to allow the Warriors to make money on the arena without ever playing a game there, though he says he’s not ready to publicly share the details. He still seems convinced that he’ll prevail. And he’s aware of how utterly quixotic this whole thing might seem—a disabled homeless man tilting at the windmills of billionaires—but he believes there’s too much at stake for him to let it go.

“I honestly believe that San Francisco is going to be ashamed of the story I’m telling,” Jones says. “I know what San Francisco is all about. And San Francisco taught me never to give up.”

There is a case to be made that this level of angst is an overreaction to a team moving all of 11 miles—that directing the Bay Area’s collective anxiety about its future toward a privately funded arena in a city teeming with social problems is aiming at entirely the wrong target. Civic opposition over the move never reached a fever pitch, and perhaps that was partly because the Warriors aren’t going very far. But now that it’s actually happening, the move has drawn newfound attention to the historical and cultural divide between San Francisco and Oakland; it’s also highlighted the fact that, despite that gulf between “neighbors”—a word Jones uses repeatedly in his letter of apology to Oakland—the two cities’ fates are inexorably linked.

San Francisco is an itinerant place—The New Yorker’s Nathan Heller, a San Francisco native, once referred to it as a “Dungeness crab of a city, shedding its carapace from time to time and burrowing down until a new shell sets”—and the Warriors have been a manifestation of that itinerancy since they got to the Bay Area in 1962. After 16 seasons in Philadelphia, all before the NBA’s merger with the ABA, the franchise uprooted and moved to San Francisco.

Those early San Francisco Warriors teams were a manifestation of the region’s quirkiness, a traveling band with no definitive home court that logged road miles like Jefferson Airplane. Owner Franklin Mieuli, the Bay Area native who bought a majority of shares in the team in 1962 and moved it (along with prodigious superstar Wilt Chamberlain) from Philadelphia, was a noted eccentric who rode a motorcycle and wore Hawaiian shirts and a Sherlock Holmes hat. The team’s original home base was the Cow Palace arena south of San Francisco, but it also played home games in Bakersfield and San Jose and Oakland, in Sacramento and Las Vegas and Seattle and in the Civic Auditorium downtown. Part of the reason for the team’s nomadic existence was because the Warriors weren’t the first priority in any of those places—if a rock concert came to town, they’d get displaced. But they also served as a guinea pig of sorts for the NBA, testing out markets while the league considered placing more teams out West.

Eventually, the Warriors gravitated toward Oakland, which made sense: The Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum Arena (now Oracle Arena) was only a few years old, and Oakland had more of a grassroots basketball presence than San Francisco. Bill Russell may have won two national titles at the University of San Francisco in the mid-1950s, but he’d gone to high school in Oakland. The Tournament of Champions, the largest high school basketball event in northern California, settled into its permanent home at the Coliseum in 1967, and the ABA’s Oakland Oaks—who signed away Warriors star Rick Barry—played there from 1967 until 1969, when they moved to Washington, D.C.

“I think Oakland was more receptive to NBA basketball than San Francisco,” says filmmaker Doug Harris, who played at Berkeley High in the East Bay, was drafted by the Warriors in 1983, and directed a film about Oakland basketball legend Don Barksdale. “They drew better crowds when they played in Oakland.”

The Warriors moved to Oakland full time in the fall of 1971. Four years later, they shocked the basketball world by winning their first championship—though they played their NBA Finals home games back at the Cow Palace because the Coliseum had committed to hosting the Ice Capades. But over the years, the Warriors, by virtue of their location and of basketball’s ties to Oakland’s place as a hub of black culture, bent more and more toward the east side of the Bay.

“There’s an urban dynamic to basketball, in a socioeconomic sense, that built up through the second half of the 20th century,” says Sam Fleischer, who grew up near Oakland attending Warriors games and is now doing his graduate studies in sports history at Washington State University. “Oakland’s just like that. It connected a sport to a community that didn’t have a lot of disposable income. Basketball was ubiquitous in that regard.”

Fleischer is one of several people I spoke to who noted the irony of all those standard overhead blimp shots of the Golden Gate Bridge during Warriors games, given that the Golden Gate Bridge might as well be on the opposite side of the ocean from Oracle Arena. Those images fit with Oakland’s long history of subsisting in San Francisco’s shadow: Iconic Chronicle columnist Herb Caen regularly mocked Oakland as a cultural backwater in comparison with San Francisco, and Liam O’Donoghue, who hosts East Bay Yesterday, a podcast about Oakland history, tells of one local historian who once referred to Oakland as San Francisco’s “ugly bridesmaid.” When the Warriors did finally move to Oakland full time in 1971, they adopted the name “Golden State” in an attempt to appeal to California as a whole (the subtext being that “Oakland Warriors” didn’t have the same glamour). And now, even as Oakland has begun to attract new investment, including major tech companies (while it’s simultaneously inherited many of San Francisco’s gentrification and skyrocketing rent issues), it still isn’t quite powerful enough to maintain one of its cultural anchors.

In May 2012, shortly after the Warriors—who had just completed their 16th losing season in 18 years—announced they planned to move to San Francisco, Oakland’s assistant city administrator, Fred Blackwell, insinuated that Oakland didn’t stand much of a chance of keeping the team. “It’s been clear to me the new owners have been interested in San Francisco since acquiring the team,” Blackwell said.

It could be argued that there is nothing inherently wrong with that ambition. The Bay Area’s more libertarian-leaning futurists might ask: Why should we castigate or penalize the Warriors owners for making a decision to maximize their profits? Particularly when, by building the Chase Center, they’re returning the Warriors to the city where the franchise first landed more than 50 years ago. Majority owner Joe Lacob, a partner at venture capital firm Kleiner Perkins, and co-managing partner Peter Guber, a Hollywood executive, were charged with resurrecting a long-moribund franchise, and they’ve accomplished that. It’s not entirely their fault that, by winning three titles—and possibly adding one more this month, should they win three more games against the Toronto Raptors in the NBA Finals—they’ve become one of the most glaring public examples of the Bay Area’s plenitude.

Yet because of the way Oakland embraced this franchise through decades of aimlessness and struggle, there’s something about this move that feels, for some longtime Oaklanders, as if it’s an inherently personal affront. This is not like losing the ever-capricious Raiders to Las Vegas, because this move reinforces the message that the Bay’s true “world-class” city still lies across the water. The Warriors had come to belong to Oakland, especially to the black community there, and now they’re departing at the same time that Oakland’s black population is in the midst of a rapid decline, thanks to gentrification that’s trickling over from San Francisco.

“When I first heard they were going to leave, I think I decided it was just talk,” says Regina Jackson, who’s lived in Oakland for 50 years and serves as the president and CEO of the East Oakland Youth Development Center (EOYDC). “And then it became like little heart palpitations with each move forward toward San Francisco. I felt sucker punched. I have been able to witness so much history, and even when they lost, they won—because they were ours. And after June, they won’t be ours anymore. And that …”

She pauses, to catch herself. “That chokes me up,” she says.

In May 2015, when Stephen Curry won his first MVP award and the Warriors were still grassroots darlings who hadn’t won a title in 40 years, Regina Jackson got a call from the Warriors, asking her to show up at the MVP ceremony in Oakland. The EOYDC, which was founded in 1973, has become a beacon of hope in a part of the city that’s often lacking in it, and Curry adopted it as one of his primary charitable causes. For decades now, future NBA players like Gary Payton and Brian Shaw—and even future NBA writers like The Athletic’s Marcus Thompson II—have come through the organization as children, but this was the center’s highest-profile moment to date.

“I didn’t even understand how big it was,” Jackson says. “I see all the cameras and all the people and I’m thinking, ‘Wow, I’ve never even been to something like this before.’ And Steph didn’t shake my hand. He gave me a hug. And he said, ‘I heard you might need a car.’”

At that ceremony, Curry donated the Kia he’d been awarded for winning the MVP to the EOYDC. Jackson calls it “Steph’s car,” and says that she uses it to transport kids back and forth to Warriors games whenever the center is gifted a block of tickets. The trip from the EOYDC to Oracle Arena is not much more than a 10- or 15-minute ride. Curry and the Warriors have made substantial donations of both time and money to the EOYDC over the years, and that seems unlikely to change in the short term, given how emotionally tethered Curry has become to the center; but Jackson’s fear is what happens in the long term, as the physical distance between the team and Oakland grows. In rush-hour traffic, it might take Steph’s car two hours to get to the Chase Center and back, and all the team’s symbolic and charitable gestures to The Town can’t change that. (It probably doesn’t help that the Warriors admitted they’re keeping the “Golden State” name not specifically to honor their years in Oakland, but because of the “equity” it provides after winning several championships.)

I have been able to witness so much history, and even when they lost, they won—because they were ours. And after June, they won’t be ours anymore. And that … that chokes me up.Regina Jackson

“Part of why I’m pissed is not just as a spectator,” Jackson says. “We’ve developed pretty comprehensive strategic partnerships with the Warriors. They paid to rebuild our gym. And then you’re like, ‘Damn, we’re being abandoned.’ And what did we do?”

These are not easy things for Jackson to reconcile; she is hopeful that the Warriors players will continue to maintain a presence long term, and that the franchise will continue to offer its support. A Warriors spokesperson said the team plans to devote roughly half of its community grants to Oakland-based groups, and that the EOYDC is likely to remain one of the largest beneficiaries. But for now, Jackson says, “The nuance in how they leave is how they stay. Will they continue to be engaged? I can’t tell you how many kids’ first basketball experience was going to a game. So how do I keep making sure that some of the most wonderful experiences in my kids’ lives will still include the Warriors?”

The striking thing about it is that many of the Warriors themselves seem to share those apprehensions about the move. The veterans, like Curry, Thompson, and Green, have come to love Oakland; they appear almost resigned to crossing the Bay against their will. The only Warrior with a home in San Francisco is Durant, who may soon be putting his luxury condo on the market, anyway. Everyone seems to understand that this move is a financial boon for the franchise, but it feels like yet another amenity that the majority of San Franciscans could never afford. Perhaps it’s telling that the closer we get to the end in Oakland, the more determinedly Curry seems to cling to the team’s past, from wearing a Run-TMC Warriors hat at last year’s championship parade—a celebration of the late ’80s and early ’90s lineup that set NBA scoring records—to the Monta Ellis jersey he wore to a game in April, honoring his former teammate (who once declared he couldn’t play in the same backcourt with Curry) and the We Believe team of 2007.

Long before Curry’s ascension, Oracle had become a symbol of Oakland’s aspirations. It was a “beacon,” as Marcus Thompson wrote earlier this year, replete with quirky characters and its own “Weed Ramp” that prefigured pot legalization by several decades. “It was organic to the city itself, and that’s what I loved about it,” says Jim Erickson, an Oakland native and longtime Warriors season-ticket holder who helped fund Allen Jones’s ballot proposition. “It was unique to have a basketball team in a small city like that.”

This was never a team that struggled to maintain its core fan base, even when that fan base achieved new stages of disillusionment, like in the weeks after the Ellis trade, or in the midst of myriad other disastrous seasons. Games at Oracle were still largely sold out no matter the quality of the basketball being played, and the crowds were both boisterous and knowledgeable. There is no conceivable way the Warriors could have felt neglected by the fans in Oakland, which is the usual story of why a franchise decides to move, and that’s the part Regina Jackson has so much trouble accepting: That her side of the Bay matters, but that the other side matters more. And while she can’t speak for all of the NBA players who grew up in Oakland and came through the EOYDC (messages put out to several of them, both by me and through Jackson, were not returned), she’s pretty sure they’re feeling the same thing.

”The head and the heart don’t live in the same space,” Jackson says. “They have different motivations and different values. And one of the nice things about the Warriors, whether you’re talking about the ‘We Believe’ teams or that [2015] championship team, was that they were all heart. We wanted them to win, but we still loved them when they didn’t. It’s just going to mean different things in San Francisco. It’s like, you can cross the bridge to the Emerald City, but there’s still no place like home.”

In the short time since Jackson accepted the keys to Steph’s car, that transition from heart to head has become apparent. In just a few years, the Warriors have blossomed from charming kids into an often-reviled cultural juggernaut, an apt mirror of the souring perception of the tech industry as a whole. Thousands of longtime residents of Oakland and San Francisco have thrown up their hands over the course of that time, resigned to living in a gone city or leaving it behind altogether. The best defense we can muster of the Bay Area in 2019 is that it might merely be clinically depressed rather than nihilistic, or that maybe the whole idea of cities like San Francisco and Oakland having “souls” is an overwrought notion in the first place. The Warriors began this journey as an underdog, one the entire region could cling to in the midst of all this change; they’ll emerge on the other side of the Bay as the manifestation of San Francisco’s new Master of the Universe status.

The longer this boom goes on, the more it seems as if the old, weird Bay Area—the region that shaped contrarians and activists like Allen Jones, and long supported ragtag franchises like the Warriors—might not be coming back. And if San Francisco is going to stay this way, and the Warriors are going to stay this way, maybe you can make the case, as team president Rick Welts essentially has, that the Warriors have become too big for Oakland; they’ve been such a sweeping success that they’re now built more for The City than The Town. The Chase Center, Welts told Forbes, is meant to rival the Staples Center and Madison Square Garden. The unspoken context is that the Chase Center is meant to further elevate San Francisco into a city like Los Angeles or New York. Maybe that’s the right play for a region that is now the center of the tech world, but it also feels like a reflection of yet another power city that’s in danger of hollowing out its old spirit.

This is the question that lingers with so many longtime Warriors fans: You can drag the head across the Bay, but will the heart come along with it? And will it even matter if it does?

If you want to trace the arc of a Warriors fan’s journey from raw euphoria to resigned pragmatism over the course of the past several years, you could do worse than to speak to Leslie Sosnick. In 2015, when The Ringer’s Jordan Ritter Conn spent time with her for a Grantland feature, Sosnick’s excitement about the Warriors was so palpable that it often interrupted her sleep. She was one of the longest-running season-ticket holders in franchise history, and went to her first game with her parents in 1963. After decades of anticipation, she was finally witnessing an NBA Finals at Oracle Arena, and while she was uncertain of what the team’s still-distant future in San Francisco might bring, she was so enamored of the present that it was hard to imagine her ever letting go.

It’s out of my league. I’m not a multimillionaire many times over. I just think the vibe is going to be totally different. And once you lose that, you don’t get it back.Leslie Sosnick

It took me some time to connect with Sosnick over the phone, because the night before we were set to speak, she took a fall and broke her kneecap. Four years ago, this would have been devastating, because Sosnick would have had to sell her playoff tickets and watch the games from home. But that was not an issue in 2019, because Leslie Sosnick and her husband, Ron Saxen, no longer have Warriors season tickets. They gave them up before this season. This was, in part, because they moved to a new house located a little farther from both Oakland and San Francisco. But it’s mainly because they found themselves doing what a lot of longtime Warriors ticket holders have as prices have continued to rise: They would sell more and more of their tickets on secondary markets, attending fewer and fewer games themselves, so that they could recoup their costs.

In the mid-1960s, not long after he opened a bail bonds business that catered to anti-war protestors and free-speech activists, Jerry Barrish bought Warriors season tickets because he fell hard for the prowess of Rick Barry. “He was the greatest basketball player I’d ever seen in my life,” Barrish says.

Over the years, Barrish gained a reputation as an artist, acquired a studio in the Dogpatch neighborhood just north of the Chase Center site, and kept going to Warriors games, most likely as the only progressive bail bondsman/salvaged-materials sculptor in attendance. He kept his seats, within a few rows of the court, even though there were years when he couldn’t give his spare tickets away. Like Barrish himself, those vintage Warriors were a reflection of all the Bay Area’s quirks; Barrish went to 41 home games a season, until he couldn’t afford to attend regularly in this new era and began to sell his tickets to an increasing number of games.

“We all knew everyone around us, and everyone was very knowledgeable of the game,” Barrish says. “You could talk to people about things that had gone on, and you could hear the ball bounce on the court and the sneakers squeak.”

The faces around both Sosnick and Barrish grew less and less familiar as the move to the Chase Center loomed. The crowds have taken on the air of a particularly rousing TED Talk, where tech moguls sit in the front row and schmooze with the players the way Jack Nicholson used to do in Los Angeles and Spike Lee does in New York. The cost of Sosnick’s tickets, if she wanted comparable seats in the new arena, was going to balloon from about $345 apiece to $600 apiece, and for the mere privilege of buying those tickets, she’d have to pay thousands more to the Warriors for what’s essentially a twist on a personal seat license, structured as an interest-free loan to the team that would be repaid in 30 years. (Barrish tells me the cost of that loan, in his case, is $70,000 up front. The Ringer was unable to get confirmation about the loan or season-ticket numbers from the Warriors by the time of publication.)

I asked Sosnick whether the Warriors offered her any kind of special deal, given her seniority. She seemed embarrassed by the notion. Why, she asked, would the Warriors offer her any unique privileges? Wouldn’t that mean they’d have to do the same for everyone? Throughout the process, she says, the Warriors emphasized the fact that they had thousands of people waiting to buy seats—according to an April article in The San Francisco Examiner, the team has already met its goal of selling 14,000 season tickets for next season, and has a waiting list of more than 40,000.

Sosnick says she understands that the team doesn’t need her; she slowly came to realize that they had begun to appeal to an altogether different crowd, and that she didn’t think it wasn’t really anyone’s fault. For her, hanging on to her Warriors tickets was a risk she couldn’t afford to take. What if, Sosnick thought, she laid out all that money, and then the Warriors fell apart in the post-Curry era? What if she could no longer sell her tickets for regular-season games, and she found herself out thousands of dollars?

“It’s out of my league, so to speak—I’m not a multimillionaire many times over,” Sosnick says. “The crowd is going to be much more corporate. I just think the vibe is going to be totally different. And once you lose that, you don’t get it back. It’s not coming back.”

While Barrish, who will turn 80 in July, has begun paying out his loan to the Warriors and will keep his seats for the first season at the Chase Center, he doesn’t plan on being around very often. He says he’ll probably sell the majority of his tickets, and he’s thinking about transferring the right to purchase the tickets granted by that $70,000 loan—most likely to a corporate entity—after next season.

Maybe all of this turnover won’t make a difference, if the Warriors have the revenue stream to sustain this run of on-court success for another generation. That shift in crowd type could wind up being far more lucrative in the long term; thanks to Lacob’s venture-capital roots, the Warriors have essentially become the tech scene’s primary public face in professional sports, and should continue to be a draw for the industry’s wealthy base. Already, many seats at Oracle are expensive enough to be out of reach both for working-class families and anyone devoid of stock options. By the time this run of Finals appearances is over, there may be enough sustained demand from corporate clients and tech-industry players that it may not matter if the Chase Center is half-full, or if the crowds turn apathetic. The arena belongs to the Warriors, and there will always be another rock concert to book to make up for a loss.

“It’s just something coming to an end,” Sosnick says. “There’s no bitterness. My family had a business for 65 years, and I’m a businesswoman, so I get it. It’s really emotional, but I kind of did my grieving.”

Perhaps the reason even a symbolic gesture like Allen Jones’s Proposition I couldn’t gain much public traction is because this is a region that’s already done its grieving. Surveys showing that vast numbers of Bay Area residents are eager to leave have grown alarmingly common; the tech behemoths and corporate interests winning out feels like an entirely unsurprising denouement in a place where the closest thing to a happy ending these days is when a beloved local business sells out for millions of dollars. The carapace of the old Bay Area has long ago been shed, and so much has changed in such an exhaustingly short period of time that the Warriors skipping over the bridge feels minuscule by comparison. Even Oakland’s current mayor, Libby Schaaf, has said more than once that the Warriors aren’t actually leaving—that they will still be here, in the Bay Area. Which may be technically true, but also served as a catalyst for community activists like Jim Erickson, who invested thousands of dollars of his own money to help Jones gather the signatures to put Proposition I on the ballot.

“I basically said, ‘Oh shit, no one is looking out for us,’” Erickson says. “When the mayor said that, it was the moment I got involved. She was just escorting them over the bridge.”

If Allen Jones is an avatar for the last vestiges of the Bay Area’s social conscience, Erickson is a representation of its raging id. Erickson is admittedly aggressive and freely profane—at one point, he says, he conducted an interview with a local TV station in which he wound up telling the Warriors owners to fuck off on camera. Erickson, who is 45, grew up in the Oakland Hills, had some success in the insurance business and wound up buying a suite at Oracle Arena several years ago. He runs a charitable foundation called Direct Help, but he has no employees and uses the foundation to hand out money to people and causes in the Oakland community. A youth basketball team needs sneakers, or a family has its breadwinner land in jail? Erickson will write them a check.

“I’m not a big-time person—I just help out with small stuff,” Erickson says. “Whenever I can go fix something, I’m just gonna go fix it myself. I’m gonna live in Oakland my whole life. I love it. I’m not leaving.”

Soon after the Warriors announced they were moving, Erickson hung a banner in his suite, denouncing Warriors ownership in rather impolite terms, until they ordered him to take it down. The Warriors had long felt like Oakland’s team to him, and now no one—not even his city’s mayor—cared that they were essentially being poached? How, he says, could he be anything other than angry?

So Erickson ranted and raved to anyone who would listen, and eventually he met Jones in a Facebook comment section. He was so struck by Jones’s conviction that they could stop this move from happening that he gave up his suite and redirected the money toward Proposition I. Their upbringings and their lives could not have been more different, but in Jones, Erickson immediately recognized a kindred spirit—someone who understood that the principles behind this move were a proxy for everything that was plaguing the Bay Area. “We’re the same person, Allen and I,” Erickson says, “except I’m a rich white guy in the Oakland Hills and he’s a homeless black guy in San Francisco. If anything, I’m the more militant one.”

Yet at this point, three months away from Chase Center’s grand opening, even Erickson has stopped believing Jones’s proclamations that he can still make this happen, that he can stand up against the inevitable engine of capitalism. It’s hard to believe in miracles in a city where the cycle of IPO wealth never seems to cease. And as Jones and I sit there and watch the Bobcat tractors scratch away the last bits of dirt from the Chase Center site, I start to wonder whether he actually believes it himself, or whether he’s just hoping against hope that I’ll quote him on something that will make its way up to the power-brokers whose attention he’s desperately trying to get.

But then, maybe it’s not about that at all. One of the last things Erickson tells me during our conversation is that this fight is not really about the Warriors; it’s more about reclaiming the ethos of a region that he believes has lost sight of its moral compass. “Just do something. Help somebody,” Erickson says. “Clean up your little corner of the world.”

A couple of days before Erickson utters those words, with the Warriors in the midst of a grueling second-round playoff series against Houston, Jones stands gingerly on the corner of 16th and 3rd, leaning on his crutches. He used to come out here regularly in his truck to check on the arena’s progress, he says, but today, he had to take the bus. When I offer to call him an Uber or a Lyft, he declines. Another bus will come soon, he says, and then he hits me with one last non-sequitur that stops me in my tracks.

“It’s just like the penguins,” Jones tells me. We’re both gazing across the street, at an arena that’s edging ever-closer to completion. “You get hundreds of penguins looking around, looking around, looking around, and then one of them starts jumping in the water. And you hope the rest follow. And that starts the march.

“And I know,” Jones says, “that’s what may have to happen.”

We shake hands and head in opposite directions. As I walk north on 3rd Street, past condos and lofts and glass office buildings in upscale neighborhoods that didn’t even exist when Jones was a kid, I wonder whether the march is already complete.

Michael Weinreb is a freelance writer and the author of four books.

This piece was updated on June 5.