When we last saw Clayton Kershaw prior to 2019, he was being bombarded by the Boston Red Sox, who tattooed him to the tune of a 7.36 ERA and a .907 OPS in his two World Series starts. Tasked with staving off elimination in Los Angeles in Game 5, Kershaw instead allowed dingers to Steve Pearce, Mookie Betts, and J.D. Martinez, unable to stifle Boston’s big bats or extend the Dodgers’ season. More discouraging still, Kershaw’s four-seam fastball speed in that start topped out at 91.5 mph, the second-lowest peak in any outing to that point in his MLB career, besting only a game in May 2018 that was sandwiched between two stints on the injury list.

Those disappointments didn’t stop the Dodgers from extending Kershaw at the end of that week, replacing the two years and $65 million remaining on the seven-year pact he signed in 2014 with a three-year, $93 million contract coda. Although a $31 million annual salary doesn’t sound so bad, it was telling that, despite his status as a franchise icon and the leverage he wielded with an opt-out clause that would have allowed him to wipe away the rest of his deal and test free agency, Kershaw was able to extract only one additional guaranteed year at a slightly reduced dollar rate. Between his nosediving velocity and his increasing infirmity—Kershaw spent a combined 163 days on the injured list from 2016-18, sidelined three times with back problems and once with biceps tendonitis—the future Hall of Famer likely couldn’t have commanded a longer-term deal at anything close to the same salary.

The ever-competitive Kershaw looked at the new agreement as an opportunity to alter the perception that he was past his prime. “It gives me a chance to prove a lot of people wrong,” he said. “I think this year especially—maybe rightfully so—there’s been a lot of people saying that I’m in decline or I’m not going to be as good as I once was. I’m looking forward to proving a lot of people wrong with that.”

Yet days after Dodgers manager Dave Roberts intimated in mid-February that the lefty was in line to make his franchise-record ninth consecutive Opening Day start, Kershaw experienced shoulder soreness in a bullpen session. The injury hampered his preparation for the season and delayed his first major league start until April 15, roughly a month after his 31st birthday. In the wake of his World Series down note, his injury-plagued—albeit effective when active—2018 campaign, and the ongoing erosion of his fastball speed, an injury to another crucial part of a pitcher’s anatomy was an extra-worrisome sign. This was a crossroads for Kershaw, one where it appeared his career could head downhill in a hurry.

So how has Kershaw, who starts Thursday against the Cubs, performed since he made his season debut? He’s been fine. Better than fine, really. Even very good, bordering on great: In 66 innings, Kershaw has recorded a 3.00 ERA (141 ERA+), a 3.39 FIP, nearly six strikeouts per walk, and a park-adjusted deserved run average that ranks 42nd out of 118 pitchers with at least 50 innings pitched. Ten starts into his 12th MLB season, Kershaw is still a highly valuable big league starting pitcher, performing at a level that would make him a roughly four-to-five-win arm over a full season (which he admittedly may no longer be capable of pitching).

Maybe that doesn’t sound so impressive, considering that when Kershaw was pitching full seasons, he routinely reached six to eight WAR. But he’s doing this with stuff that’s still slipping, pitching in a way that bears little resemblance to the approach he employed when he entered the league. He hasn’t made good on the goal of matching his past performance, but he has shown that when healthy, he can still be a crucial component of baseball’s best traditional rotation.

As we approach the midway point of the regular season, the Dodgers’ starting staff boasts the second-best park-adjusted ERA of any team since 1910, trailing only this year’s Rays, who are really running out a three-man unit bolstered by openers. (Hence the qualifier about the Dodgers having baseball’s best traditional rotation, although what passes for a “traditional” rotation today still accumulates far fewer innings than the rotations of earlier eras.) That’s not all pitching: The Dodgers’ defenders lead the majors in defensive runs saved and rank second overall in ultimate zone rating and defensive efficiency, so their glovework has made their pitchers appear even better than they’ve been. Even so, this is still a strong enough unit that Kershaw ranks only third in FanGraphs WAR among Dodgers starters, behind the suddenly unhittable Hyun-Jin Ryu and sophomore stud Walker Buehler. On the Dodgers’ stacked staff, he’s the ace in name only, but on other teams, he’d still deserve to top the rotation based on present performance alone.

When Kershaw signed his extension last November, he noted that he wasn’t counting out the possibility that his missing speed would come back.

“It very well could,” he said. “I have some ideas on maybe what I can do to improve on that, because there’s a lot of guys who are older than me, there’s a lot of guys with more innings in the big leagues, that are still maintaining their velocity. There’s some things for me definitely to look into that. There’s some things for me to work on in the offseason.”

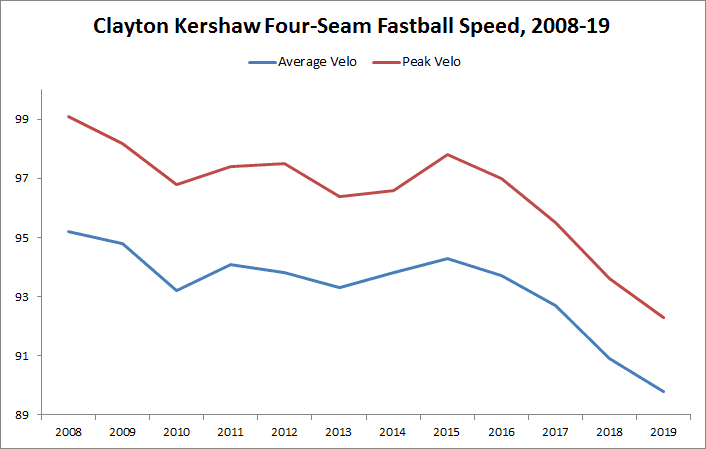

Whatever he tried—Kershaw tends not to be forthcoming about his pitching process—it didn’t work. After losing almost two ticks off his average and peak fastball speeds last season, the southpaw has surrendered more than another mile per hour this year, as shown in the graph below. Nor have his game-to-game marks evinced any signs of recovery as his spring shoulder woes have receded into the past.

Kershaw’s fastball speed has peaked at 92.3 mph this season, below each of his annual averages in every season of his fantastic twenties—the second-most-valuable twenties of any pitcher whose career started after 1908, trailing only Roger Clemens. Only 11 of the 125 starting pitchers with at least 40 innings pitched this season feature a fastball that sits slower than Kershaw’s 89.8 mph average. Kershaw is fighting a rearguard action against aging (as are we all). His stuff is retreating, and he’s trying to keep the retreat from turning into a rout. Thus far, he’s succeeding.

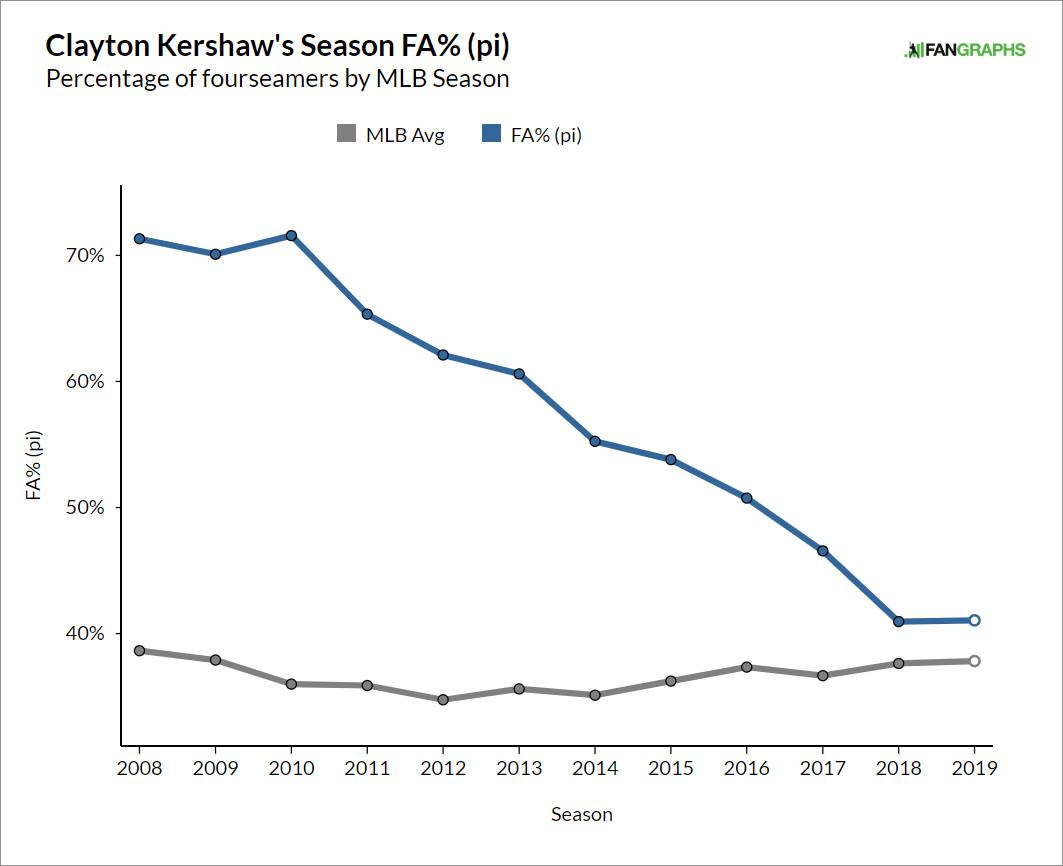

The most obvious way in which Kershaw has adapted to throwing slower fastballs is by throwing fewer fastballs.

Kershaw’s current rate of four-seamers is roughly league average, but average represents an extreme change for a pitcher who threw four-seamers 70 percent of the time during his first few years in the league. The table below shows the biggest differences in the pitch-tracking era (2008-19) between a pitcher’s fastball rate (combining four-seamers, sinkers, and cutters) in his rookie season (min. 100 IP) and his fastball rate in a subsequent season (min. 100 IP or 40 IP in 2019). Only Trevor Cahill—whose 2019 Angels have adopted an off-speed-first philosophy that currently has them on track to be the first team on record to throw fewer fastballs than off-speed pitches—has cut back on his heater to a greater degree than Kershaw.

Forget the Fastball: Pitchers Who Threw Far Fewer After Their Rookie Years

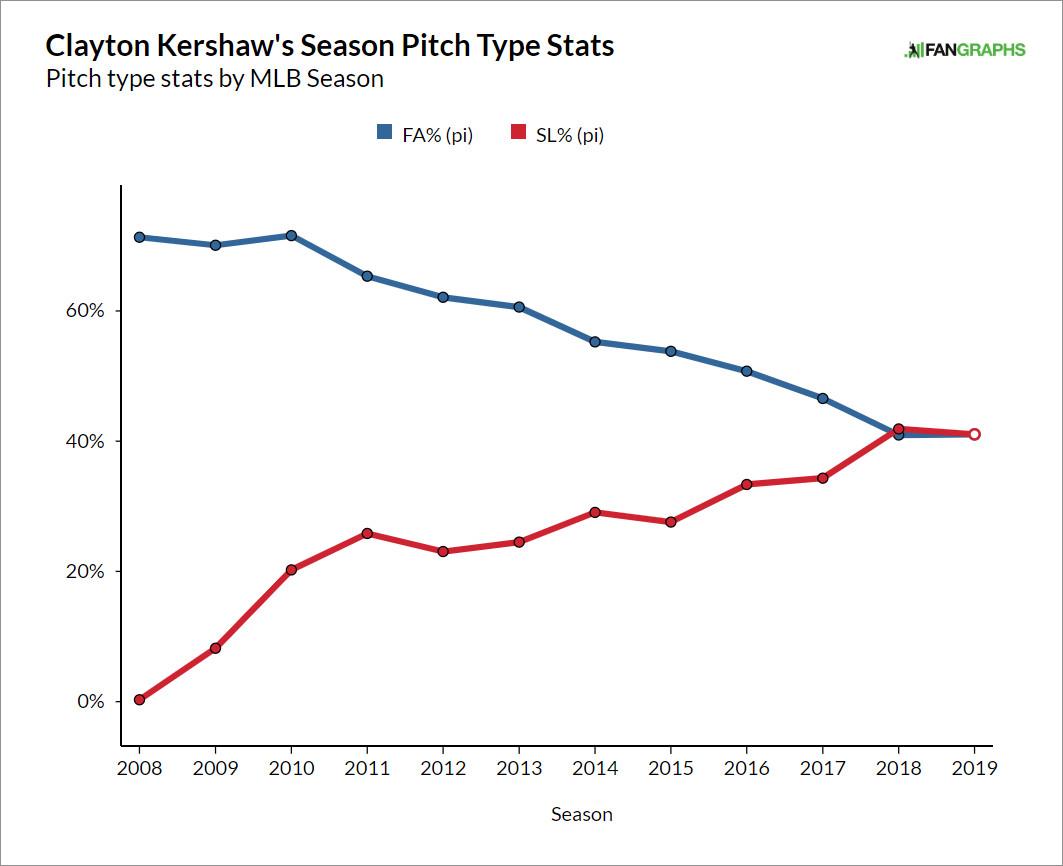

Kershaw has replaced most of those missing fastballs with sliders. Of the 153 starters who’ve thrown at least 100 innings pitched since the beginning of 2018, Kershaw and Masahiro Tanaka are the only two who’ve thrown more sliders than all types of fastball combined.

Given Kershaw’s declining fastball speed and usage, one might think that the pitch has been punished when he has opted to throw it. Thus far, though, his fastball has been more valuable on a per-pitch basis than in any previous season, and it ranks among the top five four-seamers thrown by starters with at least 40 innings thrown this year. Between Kershaw’s reduced fastball usage and the fact that we’re talking about 10 starts, we’re dealing with a pretty small sample, and his fastball is unlikely to keep avoiding damage to that degree. But it can continue to be effective as long as he keeps deploying it optimally and pairing it with a worthy slider and curve.

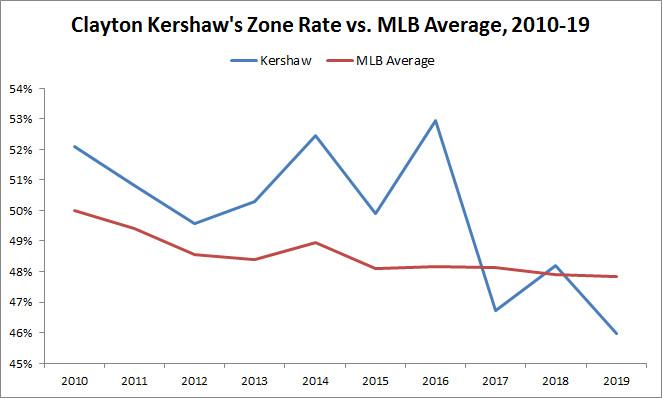

In his higher-velo days, Kershaw used to throw a lot of pitches in the strike zone, even middle-middle. He could get away with it then, when he could still blow batters away, but as his fastball speed has sunk below league average, so has the rate at which he throws pitches in the zone. These days, Kershaw tends to lurk on the periphery of the plate.

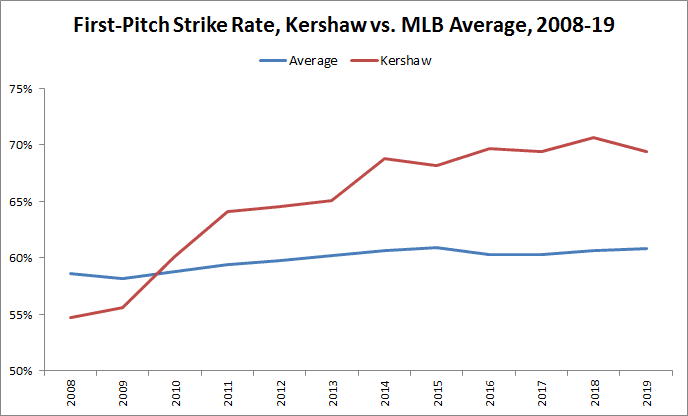

However, he doesn’t do that all the time. On the first pitch of plate appearances, Kershaw throws pitches in the zone 60.8 percent of the time, far more often than the 51.9 percent MLB average. When he’s ahead in the count, he throws in the zone only 35.2 percent of the time, less often than the 38.1 percent MLB average. In other words, he throws in the zone almost twice as often on first pitches as he does once he gets ahead. His ratio of zone rate on first pitches to zone rate when ahead in the count (1.9) is the fourth-highest among pitchers with at least 50 innings thrown this season, behind only Chris Paddack, Kyle Hendricks, and Rick Porcello. (Fellow soft-tossing teammates Ross Stripling and Rich Hill also have high ratios.)

That aggressiveness on the first pitch allows Kershaw to capitalize on the fact that hitters swing only 42.6 percent of the time on first pitches in the strike zone, compared with 80.1 percent of the time on pitches in the zone when pitchers are ahead in the count. Pounding the zone when hitters are less likely to swing allows him to rack up called strikes and maintain a first-pitch strike rate that has held up even as his fastball speeds have cratered.

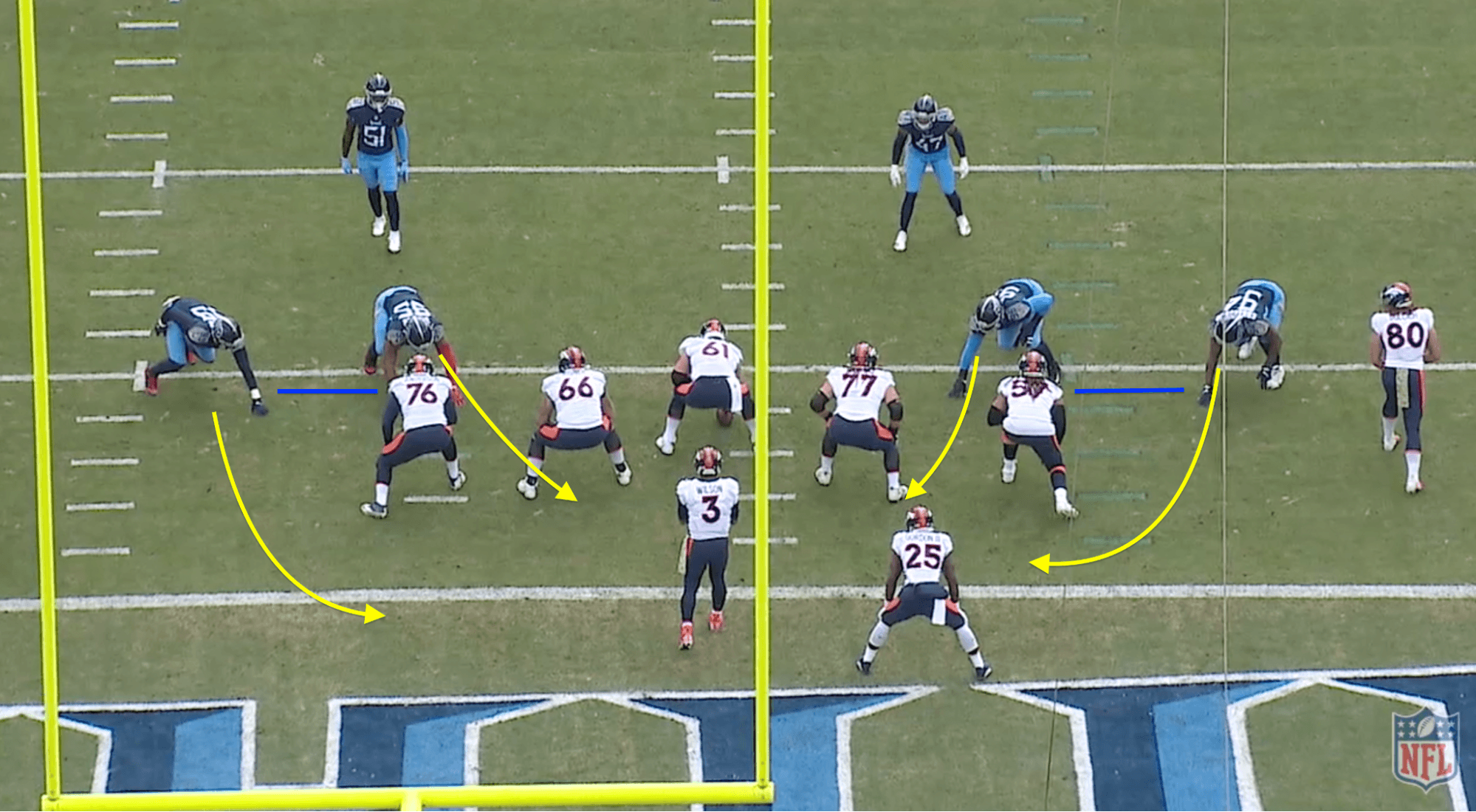

Kershaw has always cared about getting ahead in the count, but he relies on it now in a way that he didn’t when his stuff left him with more margin for error. Once he gets ahead, he goes in for the kill. The heat maps below show where Kershaw concentrated his curves and sliders when ahead in the count from 2014-16 and where he locates them now. Darker colors represent the regions where he threw (and throws) most often, and the pitch-black point has migrated from inside the strike zone to well below it.

That, then, is the latter-day Kershaw formula: sneak strikes by hitters on the first pitch, and then, when they’re on the defensive, tempt them to chase way out of the zone. That approach has kept Kershaw ahead in the count much more often than most pitchers, and with hitters back on their heels, he’s allowed a lower-than-average exit velocity. The holistic strategy is working quite well.

It’s a credit to Kershaw that despite his stardom, he hasn’t clung to what worked in the past and been bullheaded about making concessions to age. In some respects, he’s adopted a survival plan employed by most pitchers, who collectively tend to throw fewer fastballs and fewer pitches in the strike zone as they age. He’s just taken it to the extreme, and he also started his decline from a much more elite level of performance than virtually any other pitcher. (This is, after all, Clayton Kershaw.) Research has shown that starters tend to allow roughly 0.3 runs more per nine innings for every mile per hour their fastballs lose. Kershaw has lost about 4 miles per hour since his heyday, and now he’s, say, a 3.1 ERA guy instead of a 1.9 ERA guy. The regular relationship holds true, but whereas a loss of that magnitude would knock some starters out of the league, it’s simply turned Kershaw into an above-average arm instead of one of the best of all time.

Even in decline, Kershaw has a deceptive delivery that likely makes his subpar fastball play up. He has solid command of his most important pitches: According to Command+, a metric published by STATS that attempts to assess a pitcher’s ability to hit his spots, Kershaw’s fastball command (108, where 100 is average) ranks 27th out of 75 pitchers who’ve thrown 400 heaters this year, and his slider command (117) ranks 12th out of 93 pitchers who’ve thrown 200 sliders. And even though his pitches take longer to reach home plate, he has stuff that most pitchers—even hard throwers—would envy: His fastball still seems to rise, his slider still slides, and his curve gets great downward movement.

Kershaw’s current coping strategy won’t work forever. The velo he’s lost likely isn’t coming back, and if his fastball speeds keep dropping (or hitters start expecting those first-pitch strikes), he may reach a point where he can’t keep compensating. Pitchers in their 20s tend to weather velocity loss better than pitchers in their early 30s, probably because the former have adjustments to make, while the latter have already run out of tricks. Kershaw’s days of lowering his career ERA in each succeeding season are over; that elevator is only going up. But as long as his back, biceps, shoulder, and assorted other body parts don’t betray him, he could be heading for a relatively graceful decline phase, more CC Sabathia than Félix Hernández. And with the rest of his rotation-mates more than keeping pace, that may mean more cracks at World Series success.

Thanks to Kyle Cunningham-Rhoads of STATS for research assistance.